Everything, Everywhere, All at Once: Franklin W. Smith’s Attempt to Bring the Ancient World to DC

On your list of sights to see are Egyptian pyramids, a Persian throne room, tombs from Rome, an Alhambra patio, and a medieval German castle. But this isn’t an itinerary for a world tour. If one ardent lover of history had gotten his way, all you would have needed to see it all was one train ticket to Washington, DC!

By the eve of the 20th century, it was clear America was on its way to becoming a political and economic force to be reckoned with. But to Boston businessman Franklin Webster Smith, it lagged pathetically behind the Old World on the cultural stage. Other nations had their compendiums of cultural treasures: Italy’s Uffizi gallery, Russia’s Hermitage, and France’s renowned Louvre. America, on the other hand, suffered a “national destitution” of cultural institutions, and was “the only nation which… has done nothing to acknowledge the claims of art,” according to Smith.1

So, perhaps compensating for lost time, he came to DC in 1890 to unveil his plans – on a gloriously dizzying scale – for a new museum in Washington.

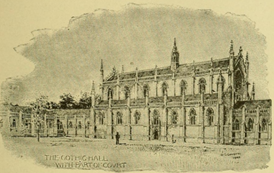

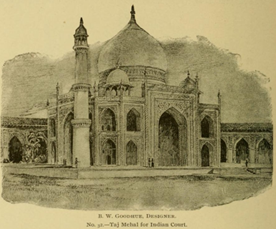

court. The medieval and Renaissance

parts of the Galleries would "inherit an

embarrassment of riches" in artifacts and

relics. [Source: National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington by Franklin Webster Smith, 1900]

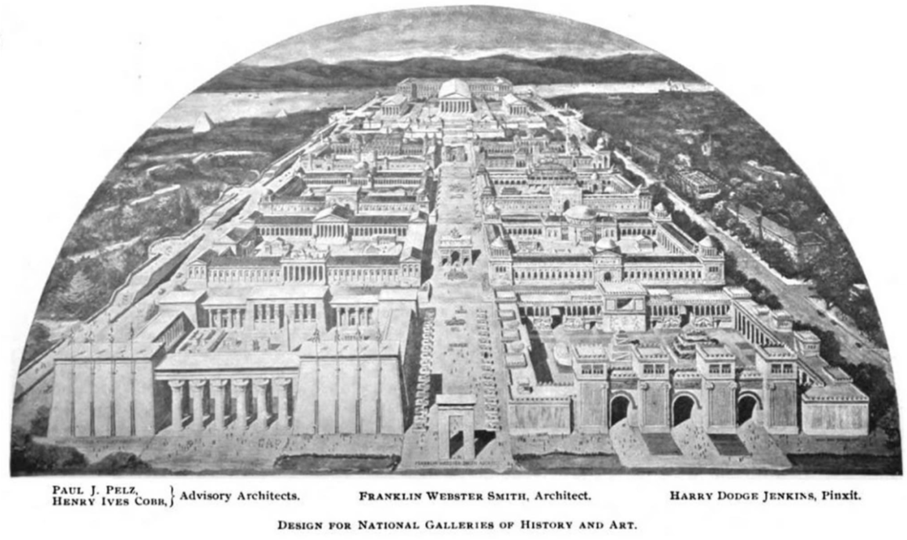

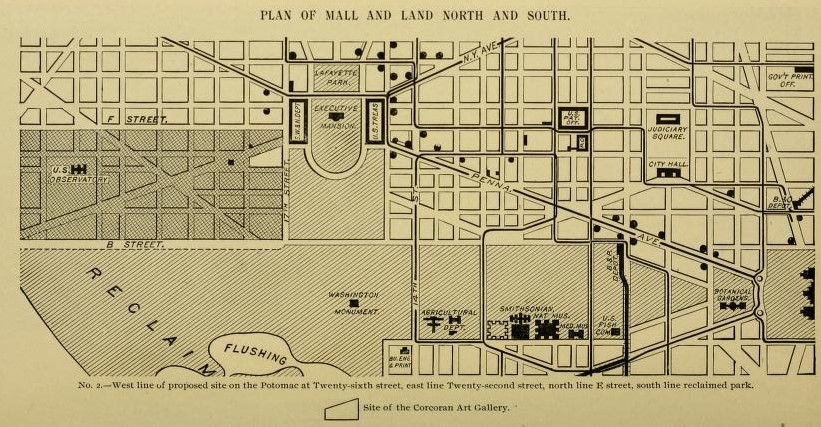

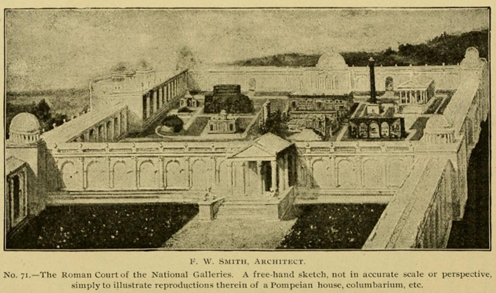

But this wasn’t just any museum. Smith’s proposed National Galleries of History and Art was nothing short of an attempt to cram millennia of world history onto one spot. The sprawling complex centered on eight immense galleries devoted to the art, history, and civilizations of Rome, Egypt, Assyria, Greece, Babylonia, the Islamic empires, India, and Medieval Europe.2 A “mélange” of “any architectural style you can imagine,” each gallery would flank a long avenue lined with Egyptian sphinxes.3 At the end of that avenue, over the Potomac river, would sit an enlarged replica of the Parthenon, which would be a temple to famous Americans and episodes of national history. Outside the walls would be a park called Istoria with faithful reproductions of Roman ruins.4

Neither was there any shortage of the marvels Smith planned to pack inside of his galleries: “Egyptian palaces; Roman baths; sections from the Catacombs; part of the great mosque of Cordova; a castle from the banks of the Rhine; the Sphynx and the Pyramids, in miniature; the Town Hall of Antwerp, a salon from Fontainebleau, a court from the palace of the Infanta in Saragossa, Spain; an old Norman gateway; Japanese and Chinese dwellings; an Egyptian mosque.”5

If—somehow—Smith had space left over, he also wanted to include for visitors’ perusal replicas of the homes of Shakespeare, Martin Luther, and Mozart, as well as Marie Antoinette’s cell and rooms from the Tower of London.6

Inside the galleries, historical paintings would “[set] forth in realistic and truthful form the events of history.” Archeological relics would show the chronological progress of each civilization, and charts over the walls would show migrations, political divisions, and population changes. This chronological structure would make the Galleries better than their counterparts across the world because they would be built “upon a grand systemic plan, greatly surpassing all existing museums with their fragmentary collections.”7 In the basement would be a library “to rival the British Museum.”8

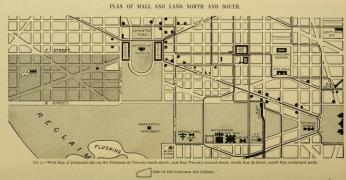

Washington Monument, and Capitol.

[Source: National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington by Franklin Webster Smith, 1900]

The scale of the proposal was almost ludicrous; Smith wanted a complex with “no lack of room for centuries.” 9 The Galleries would be situated near the White House and take up nearly half the current neighborhood of Foggy Bottom. Smith was seeking to purchase over 200 acres of land and cover at least sixty to seventy acres with the galleries.10

For reference: the Louvre, the world’s largest art museum, is only fifteen acres. Smith was proposing a project four to six times the size of the Louvre.

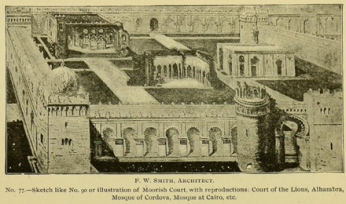

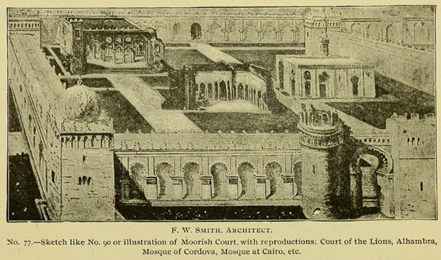

the Moorish Court. [Source: National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington by Franklin Webster Smith, 1900]

Take for example his plan for the Moorish Court. You would enter through the Puerta del Sol of Toledo, its keyhole arch rising high above you in Mudejar glory. Inside, you could wander under the arches of Cordoba’s Great Mosque, visit the famous stone lions of the Alhambra, and consider the majesty of Cairo’s Great Mosque. Each of the corner towers around the walls would be “casts or reconstructions of famous monuments or fragments of the richest constructions” according to the style and period of the courts they enclosed.11

One of the most strikingly modern points of Smith’s plan was the level of immersion he wanted visitors to have. Guests were meant to appreciate these cultures as though they were walking through their great achievements and everyday realities. In each gallery, “Greek, Roman, and Hindu professors in appropriate costume” would teach in their native languages in lecture halls decorated and styled as though they had been plucked from Athens or Babylon.12 All these carefully copied wonders of the world, Smith said, would “inspire enthusiasm to study realistic portrayals of ancient life.”13 Imagine if the Smithsonian took over Epcot and sprinkled in scholars and reenactors: that, more or less, was Smith’s vision for his Galleries.

The project was the grandest step yet in Smith’s lifelong interest for bringing an appreciation of global art and culture to America. In 1854 he visited the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, which featured an explosion of historical replicas in its Fine Arts courts. He came away especially impressed with the Egyptian Court. Two decades later, he chaired the Bazaar of the Nations in Boston, creating a dozen full-scale copies of houses from Switzerland to China. Immersion and live history were also themes that dominated his personal projects. In New York and Florida, Smith had built models of Moorish and Roman villas. His House of Pansa—the Roman reconstruction—had “great success,” attracting over 60,000 visitors.14

To fully articulate his plans, Smith compiled them into a book and published it at his own expense. This Design and Prospectus set out in minute detail the cost, construction, rationale, and design of the Galleries, how they would compare to and improve upon other famous museums, and why they were culturally and educationally beneficial. Over 400 pages long, the book is a fascinating, scrupulous testament to Smith’s ambition, devotion to, and belief in his project: he sent a copy to every member of Congress in hopes of winning their support.15

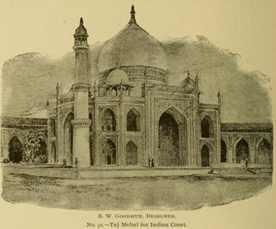

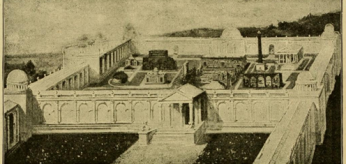

Court. [Source: National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington by Franklin Webster Smith, 1900]

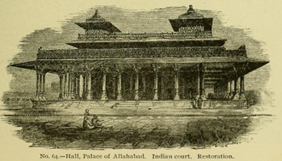

the fort of Allahabad, also meant for the

Indian Court.

[Source: National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington by Franklin Webster Smith, 1900]

Glamorously illustrated and enticing in scale, the National Galleries of History and Art proposal caught the attention and imagination of both press and public. Smith often pitched the Galleries as a patriotic enterprise, and reporters agreed. Scientific American wrote that the Galleries would be an aesthetic and educational gift to the nation.16 The Decorator and Furnisher noted with admiration that it put the world’s wonders within reach of millions of Americans for whom overseas travel was far too expensive. “[The Galleries’] realization,” the editorial concluded, “will crown the man that conceived it with undying fame.”17

Journalists were also curious about how the massive project would be funded. As one reporter said, looking at the design alone was enough “to empty the Treasury of the United States.”18 Indeed, conservative estimates put the project at anywhere from five to ten million dollars.19 Smith had two solutions: cut costs, and seek donations. The Galleries, mighty as they looked, were reproductions only in scale. The massive columns would be hollow, and the roof made of glass to cut material and lighting costs. The buildings themselves would be made of concrete—a cheap, sturdy material that was also the “principal material of ancient Rome,” as Smith loved to remind people.20 21

For the bulk of the money, he turned to the government. He began by petitioning for $200,000 which was “justly due” in return for a lawsuit that Smith claimed had unfairly targeted his business during the Civil War.22 The money should not go to him, but rather towards the construction of the Galleries. Additionally, the Galleries would be built on land that the government already partly owned; he wanted Congress to buy the rest of the acreage for $370,000 and then appropriate more money over several years to fund construction.

But Smith conceded that “Congress has always been far behind the people in patriotic pride for the national capital,” so he also looked to private donors.23 With a bit of marketing flair, Smith would proclaim his search for “ten wise men” to contribute $100,000 each in order to kickstart construction of the Greek and Roman pavilions. He also considered a scheme of selling low-interest bonds that would be backed by a small admission fee upon completion of the museums.24

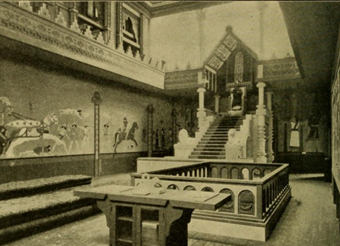

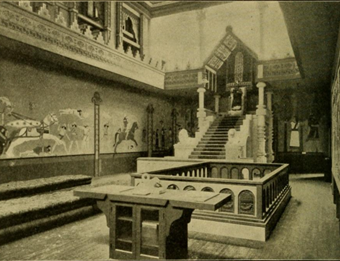

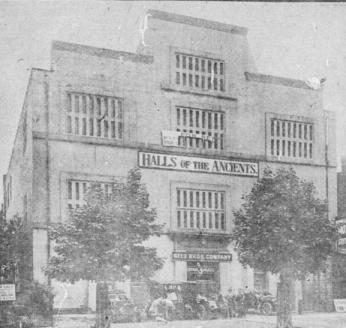

The financing plan was ambitious to say the least and money was slow to materialize. But Smith was not one to wait around. While he waited for the funds to build the real Galleries, he would open the Halls of the Ancients, a kind of proof-of-concept on a much smaller scale. Barely two blocks from the White House, he built the façade of the Temple of Karnak (down to its smallest hieroglyph) on New York Avenue. In February of 1899, an advertisement appeared in the Evening Star announcing the Halls’ opening, promising a “gorgeous blue and gold” Assyrian throne room, a Moroccan hall, and a full-color copy of the Book of the Dead—72 feet long!25

with King Sennacherib on the Throne of Xerxes.

[Source: National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington by Franklin Webster Smith, 1900]

Meant to be a “full reproduction” of Egyptian, Greco-Roman, and Assyrian art, architecture, and life, Smith filled it with art, casts, models, and cultural artifacts from his own collection.26 For example, the Egyptian “Hall of the Kings” was defined by twelve 30-foot columns covered with drawings: “the most imposing… reconstruction from Egypt that has yet been attempted,” Smith boasted. Over the walls, Egyptian divinities made solemn processions copied from the walls of ancient temples. At the far end of the hall stood a pavilion and throne, which Smith planned to fill with a statue of Rameses II, as though he were preparing to receive his American visitors.27

The Hall enjoyed popularity during its lifetime as a museum, classroom, lecture space, and object of curiosity. In 1902, students from the Franklin School performed for guests during a dinner, “receiving in ancient costume and using Latin.” They even recreated a wedding ceremony based on a fresco depiction from the 1st century BC. “The visitor is made perfectly at home in a house of twenty centuries ago,” a reporter from the Times concluded.28 But as much affection and praise as the Halls received, Smith always believed that the impact of the full Galleries would be far greater.

Ancient Hindu temples and Greek atriums, though, certainly aren’t to be found in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood as it is today. Nor can you walk among sculpted Gothic piers or under the crenelated ceilings of a medieval mosque without heading first to Dulles Airport. What happened, then, to this public works pipe dream?

entrance sign can still be seen on the facade.

[Source: The Washington Times]

Smith’s beloved design did eventually make its way into Congress thanks to his ally and supporter, Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts. In February of 1900, Hoar presented Smith’s petition outlining the design for the Galleries. In return for the appropriations, Smith promised that he would “devote himself” to seeing it completed and donate his own personal collection to the museums.29 The item was referred to the Committee on the District of Columbia. However, it came along at a bad time. The Philippine-American War was in full-force, and a cultural proposal sunk to the bottom of most politicians’ priorities. The petition died in committee, and Hoar’s death in 1904 deprived Smith of a key ally in the legislature, ensuring the Galleries would never see the Senate floor.

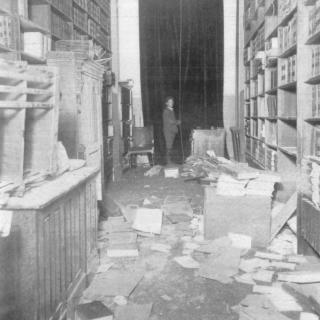

The Halls of the Ancients had a slightly more tragic end. Smith operated the attraction until 1905, when he was sued for past-due rent. Though Smith had reworked the building and owned everything inside of it, he did not own the land. Worse still, it came out that the owners owed $65,000 on a mortgage. If the money did not turn up, the plot would go to auction… And that’s exactly what happened. In 1906 a real estate developer turned this Egyptian temple into a garage, extinguishing the last flicker of Smith’s dream for an antiquarian wonderland.

Perhaps the Galleries were doomed from the start: too big, too expensive, a decadently overstimulating monstrosity of a museum. But it is fascinating to imagine a full facsimile of world history balled up in Washington.

Think about that the next time you walk through Foggy Bottom: had history taken a different turn, you could have been strolling over a rebuilt Appian Way, past an avenue of sphinxes, on your way to inspect Arabic engravings from the Alhambra before meeting your friends for a Latin lecture in a Roman theater!

Footnotes

- 1 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. 25, 28

- 2 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900.

- 3

Smithsonian Magazine. “The Monuments That Were Never Built.” Smithsonian Magazine, November 23, 2011.

- 4 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. 98

- 5

"FROM THE BANK THE NILE: AN EGYPTIAN PALACE TO BE BUILT IN WASHINGTON. THE FIRST STEP IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF A GREAT GALLERY OF HISTORY AND ART IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL -- WHAT IS PROPOSED." New York Times (1857-1922), Apr 23, 1892.

- 6

"A GREAT TEMPLE OF ART: FRANKLIN W. SMITH CONFIDENT THAT HIS DREAM WILL BE REALIZED. SITE OF THE PROPOSED GALLERY THE OLD NAVAL OBSERVATORY THE ONLY AVAILABLE LOCATION IN THE DISTRICT--SOME IDEA OF THE VASTNESS AND SCOPE OF THE BUILDING PLANS." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 22, 1891.

- 7 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. 67

- 8

“Editorials.” The Decorator and Furnisher 17, no. 6 (1891): 199–200.

- 9

"A NATIONAL ART GALLERY.: MR. FRANKLIN W. SMITH'S PLAN OUTLINED IN AN ADDRESS." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 17, 1891.

- 10

"THE STORY OF A PETITION: PLEAS FOR JUSTICE, ART. AND HISTORY ALL IN ONE. FRANKLIN W. SMITH ASKS MONEY FROM THE GOVERNMENT -- THE CLAIM ALLOWED, THE CASH WOULD GO FOR A GREAT GALLERY AT WASHINGTON." New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 09, 1892.

- 11 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. 99

- 12

"HISTORY AND ART IN WASHINGTON.: MR. SMITH'S ILLUSTRATED LECTURE ON HIS PROPOSED NATIONAL GALLERY." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 05, 1893.

- 13 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900.

- 14

"FOR A NATIONAL GALLERY: OUTLINE OF FRANKLIN W. SMITH'S STUPENDOUS SCHEME. HIS DESIGN IS COMPLETE IN EVERY PARTICULAR AND HE PROPOSES TO STAKE AN EARLY MOVE ON CONGRESS -- WANTS SPACE IN THE GROUNDS OF THE SOLDIERS' HOME." New York Times (1857-1922), Dec 17, 1892.

- 15

Graboyes, J.S. “In the Halls of the Ancients: The Imagined Washington, DC, of Franklin Webster Smith.” Duck Pie, February 19, 2018.

- 16

“A National Gallery of History and Art.” Scientific American 67, no. 15 (1892): 228–228.

- 17

“Editorials.” The Decorator and Furnisher 17, no. 6 (1891): 199–200.

- 18

"FROM THE BANK THE NILE: AN EGYPTIAN PALACE TO BE BUILT IN WASHINGTON. THE FIRST STEP IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF A GREAT GALLERY OF HISTORY AND ART IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL -- WHAT IS PROPOSED." New York Times (1857-1922), Apr 23, 1892.

- 19

“A National Gallery of History and Art.” Scientific American 67, no. 15 (1892): 228–228.

- 20

"FROM THE BANK THE NILE: AN EGYPTIAN PALACE TO BE BUILT IN WASHINGTON. THE FIRST STEP IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF A GREAT GALLERY OF HISTORY AND ART IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL -- WHAT IS PROPOSED." New York Times (1857-1922), Apr 23, 1892.

- 21 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. v

- 22

"THE STORY OF A PETITION: PLEAS FOR JUSTICE, ART. AND HISTORY ALL IN ONE. FRANKLIN W. SMITH ASKS MONEY FROM THE GOVERNMENT -- THE CLAIM ALLOWED, THE CASH WOULD GO FOR A GREAT GALLERY AT WASHINGTON." New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 09, 1892.

- 23 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. 42

- 24

“Editorials.” The Decorator and Furnisher 17, no. 6 (1891): 199–200.

- 25 Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.), 03 Feb. 1899. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 26

"HALL OF THE ANCIENTS.: FRANKLIN W. SMITH WELCOMS MANY VISITORS TO HIS INTERESTING EDIFICE." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Feb 05, 1899.

- 27 Smith, Franklin Webster. National Galleries of History and Art: The Aggrandizement of Washington ... US Government Printing Office, 1900. pp. 14-18

- 28 The Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 16 Jan. 1900. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 29

"NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART.: MR. FRANKLIN W. SMITH OFFERS HIS LARGE COLLECTION TO THE GOVERNMENT." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Feb 13, 1900.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)