Hugo Deffner and the Long Road to Accessibility in Washington

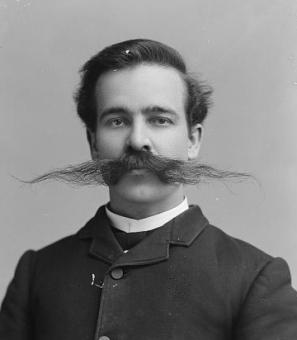

Activist Hugo Deffner had been campaigning for accessible architecture for over a decade when he was invited by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to come to Washington to receive the 1957 “Handicapped Man of the Year” award. Deffner, a 68-year-old insurance salesman and wheelchair user, hailed from Oklahoma City where he had been a staunch advocate for accessibility. Thanks to his efforts, his local YMCA, public library, public high school, and Methodist church were made wheelchair accessible. Deffner’s activism went beyond his hometown as well. He wrote letters to President Eisenhower and other legislators about the importance of setting national standards for accessibility.[1]

Deffner was a man ahead of his time. Though he promoted the installation of ramps to make buildings more accessible, he declared that, “a ramp is nothing but an apology for bad design.” He wanted accessibility to be an essential, not an afterthought. He also pushed against the prevailing idea at the time that accessibility was a benevolent favor to disabled people. “[Accessibility is] a question of restoring something that was taken from them [disabled people], not just giving them something,” he said.[2]

The Oklahoman’s tireless work led President Eisenhower to tap him for the award in May of 1957. Deffner was honored, telling his local newspaper that the recognition was “above anything I had ever hoped for.” He was surprised to receive the award but, “even more surprised some time back when I read about the many other states that endorsed the nomination… it means the idea is beginning to take hold.”[3]

So it was with great pride that he arrived in Washington with his wife. They stayed in the illustrious Willard Hotel, just a few blocks away from the Departmental Auditorium (now the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium) where the award ceremony would take place.[4] On the day of the ceremony, a crowd of about 1,400 spectators gathered in the auditorium awaiting Deffner’s arrival. The audience included Oklahoman political leaders, doctors, and community members who had flown in to celebrate their fellow citizen’s achievements.[5] However, when the man of the hour arrived outside, he encountered the very foe whose fight had led him to Washington: stairs. Hugo Deffner, a national hero, had to be carried into the auditorium by a pair of Marines.[6]

After this likely humiliating entrance, Deffner was presented with a trophy by President Eisenhower and made a speech. He spoke about his campaign for accessibility, but also cited the need for continued efforts. Though he could freely enter many public buildings in Oklahoma City, he said he had yet to be able to enter a post office. Eisenhower said of Deffner, “I hope he’s having every success… because sometimes steps do seem steep even to me.”[7]

Deffner passed away just three years after receiving his award, but his legacy lived on across the country, and in Washington especially.[8] Deffner’s inability to enter the auditorium alerted legislators to something that disabled Washingtonians knew all too well: the nation’s capital was inaccessible to many American citizens. The decades that followed were an awakening for the city of just how inaccessible it was.

In 1964, an anonymous Washingtonian wrote to the Evening Star to voice their struggles with the city’s lack of accessibility. “For those of us with limited mobility, architectural barriers prevent free access to those buildings which we must enter to work, to vote, to worship, to learn, to play, or even to buy a stamp. To fulfill our responsibilities as citizens, we often must circumvent these barriers by entering through the rear door, where freight is hauled in and garbage hauled out, and make our way through coal bins, storerooms, and boiler rooms to reach a freight elevator which can accommodate our wheelchairs.”[9]

Another Washingtonian detailed the difficulties that he experienced simply paying his taxes. “The fact that I use a wheel chair as a means of locomotion in no way reduces or limits my responsibilities to pay taxes… My last report was scrutinized and I was instructed to report to my local Internal Revenue Office… I found an impressive building… it had huge entrances on each side—that could be reached only by climbing an equally impressive flight of steps… I located the ‘vehicle entrance’… went down a precipitous incline, dodging postal trucks… I negotiated a ramp, a loading dock, the building’s boiler room and finally reached a freight elevator that did not stop at my floor.”[10]

In 1961, the American Standards Association set standards for accessible design for federal buildings that included requirements for wide entrances and sidewalks, larger bathroom stalls, ramps, and designated parking. However, these standards were merely recommendations and, as the anonymous testimonials show, they were not enforced.[11]

Accessibility was a problem not only for locals, but for visitors to Washington. In the 1960s, the tourism industry began to recognize the importance of accessibility. What message was Washington sending about America if thousands of visitors couldn’t access the Lincoln Memorial, the White House, or even ride a bus in their nation’s capital?[12] As James L. Abdnor, a congressional representative from South Dakota, remarked, “It is absurd and regrettable that in our Nation’s Capital one can visit the Washington Monument in a wheelchair, but not be afforded the opportunity to peer from its windows. Once inside the National Archives, the U.S. Constitution and other meaningful documents are unable to be seen from a wheelchair.”[13]

Opponents of accessible architecture argued that it catered to the few at the expense of the many. But, in fact, the cost of including accessible features was negligible in most cases compared to overall construction costs.[14] Joseph Carvajal, the executive secretary of the Commissioners Committee on the Employment of the Handicapped said, “Some of these things that help the handicapped are bound to be a little more expensive, like moving ramps in a subway station are a little more expensive than stairways. But they are safer, too, not only for the handicapped, but the general public. You can take it as a rule of thumb: Whatever is better for the handicapped is safer for the average person, too.”[15] What Carvajal is describing is known today as the curb-cut effect. A curb cut is not only beneficial to wheelchair users, but also to people pushing strollers, carts, or suitcases.[16] Even Eisenhower had understood the curb-cut effect, when he remarked that Deffner’s work benefitted him too when stairs felt too steep.

An organization called the Architectural Barriers Project was instrumental in raising awareness and pushing for change in accessible architecture in Washington. In 1966, the organization’s head, Janet W. Fay, reminded the public that, “Buildings have always been built with stairs, or with revolving doors, or with narrow bathroom stalls. The architects and the builders just don’t realize that these things are problems unless they are called to their attention.”[17] The next year, the Architectural Barriers Project published a guidebook that informed residents and visitors about which local businesses, restaurants, hotels, places of worship, and tourist destinations were accessible and how to request accommodations.[18] Entries in the guide included:

Corcoran Gallery of Art… Arrangements can be made to use ramp at service entrance on E St. NW.

National Collection of Fine Arts… Two steps.

The White House… Special arrangements must be made through senator or congressman to use elevator.

Franciscan Monastery… Long ramp along side of church to main entrance. Catacombs inaccessible.

Islamic Center. Mosque… Steps. Two gentlemen there will assist. If you cannot remove your shoes due to braces please bring something to cover them.

Holiday Inn at Rhode Island Avenue NW… Curb from driveway to lounge. Elevator. Bathroom doorways 21’’. Go through kitchen to reach dining room.

Hot Shoppes Restaurant, New Hampshire Avenue… Banquet room may be reached by freight elevator.[19]

This guide shows that even the smallest detail, like the width of a doorway, could bar a disabled person from entering a building. Hugo Deffner called this problem “front door segregation.”[20] Groups like the Architectural Barriers Project, both national and local, worked to dismantle this segregation in public buildings, transportation, and housing.[21]

Between the tireless work of advocacy groups and the memory of Hugo Deffner’s lack of access to the Departmental Auditorium, Congress took notice. Finally, in 1968, Congress passed the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA), which expanded the standards set by the American Standards Association in 1961 and required all new or renovated buildings built or leased with federal funds to be made accessible.[22] Because the ABA applied to federal properties, it had significant implications for Washington.[23]

The act was a major acknowledgement of the difficulties that disabled people faced in accessing the most basic services… but not much changed after its passage. Most new construction was still not designed to be accessible, and repairs were not made to existing structures to increase accessibility. There was hardly any effort from the government to monitor or enforce compliance with the act.[24]

Disabled people continued to advocate for accessibility in Washington through both grassroots activism and formal appeals to the federal government. Larry Kirk, a federal housing official and double amputee, cited the impact of activism, saying, “They are becoming a bit more militant from their wheelchairs. The squeaky wheel gets the response.”[25]

The squeaky wheel began to see some results. In 1973, just a few years after the ABA was revamped, Congress passed another landmark piece of legislation, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, though it took several more years to be implemented. Section 504 declared that discrimination against disabled people in federally funded programs was unlawful. This built upon the ABA because a lack of physical access was considered discrimination. Section 504 also set aside federal funding for states to make their programs more accessible. Even with the addition of Section 504, the ABA remained an important piece of legislation because it outlined specific measures for making architecture accessible and for enforcing those measures. Once Section 504 was finally enacted, it bolstered the ABA because disabled people could now cite inaccessibility as not just an inconvenience, but a breach of their civil rights.[26]

Progress continued to sputter, however. In 1975, seven years after the ABA was passed, a congressional subcommittee hearing revisited the act to evaluate why it had been so ineffective. Congress took steps to increase the impact of the act by creating more specific language about access requirements and measures to more strictly enforce compliance.[27]

The Bicentennial was another driver in increasing accessibility, especially for Washington's many tourist attractions. At the same hearing where Congress addressed the ineffectiveness of the ABA, Representative Abdnor introduced a resolution to remove architectural barriers for the Bicentennial. Among other improvements, the National Park Service installed elevators at the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. By 1978, a spokesperson for the National Park Service (which oversees the Mall) reported that, “Overall, handicapped visitors are much better served on the Mall than they were three years ago [before the Bicentennial]—with additional curb ramps and parking spaces and the two closed roadways.”[28]

The legacy of the Architectural Barriers Act may be imperfect, but it was the first domino in a series of life-changing laws. In 1990, disabled people’s rights were expanded once more with the Americans with Disabilities Act, which declared discrimination against disabled people illegal not only in federally funded programs, but in all organizations and activities, public and private.

If Hugo Deffner were alive today, he would find Washington much improved. A wheelchair user visiting the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium today could approach the building with ease on wide sidewalks with curb cuts on every corner. The building has ramps at each side entrance with a “push to open” button in front of each door. Disabled people still face many architectural barriers, from private businesses that are lax on adhering to ADA standards to arduous processes of calling ahead to secure accommodations. However, through the continued work of legislators and activists like Hugo Deffner, Washington has become one of the most accessible cities in America.[29]

Footnotes

- ^ "Oklahoman Is Winner of ‘Handicapped’ Trophy,” The Evening Star, Apr 7, 1957.

- ^ Goddard, Mary, “Crippled Cityan Rides Into National Acclaim,” Oklahoma City Times, Apr 6, 1957.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Robinson, Ray, “Handicap Access Faces Council Test,” The Oklahoman (Oklahoma City, OK), Jul 19, 1982.

- ^ Cromley, Allan, “Handicapped City Man Is Given Trophy by Ike,” Oklahoma City Times, May 23, 1957.

- ^ Weintraub, Boris, “Getting Around in a Wheelchair, The Evening Star, May 8, 1966.

- ^ Cromley

- ^ “Sooner, Winner of U.S. Award, Dies of Stroke,” Miami Daily News, Apr 20, 1960.

- ^ McKelway, John, “The Rambler… Hears of a Cause,” The Evening Star, Apr 29, 1964.

- ^ Mckelway, John, “The Rambler… Gets a Guide Book,” The Evening Star, Oct 9, 1967.

- ^ Weintraub

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The effectiveness of the Architectural barriers act of 1968 (Public law 90-480) : hearings before the Subcommittee on Investigations and Review of the Committee on Public Works and Transportation, House of Representatives, Ninety-fourth Congress, first session, October 7 and 20, 1975.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Weintraub

- ^ “The Curb Cut Effect,” PolicyLink.

- ^ Weintraub

- ^ McKelway, John, “The Rambler… Gets a Guide Book, The Evening Star, Oct 9, 1967.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Nelson, Mary Jo, “Building Designers Bow to Foe of Stairs,” Oklahoma City Times, Oct 18, 1958.

- ^ Lide, Francis, “Victims of Paralysis Join in Efforts to ‘Open Doors,’” The Evening Star, Mar 1, 1964.

- ^ Gold, Susan Dudley, Landmark Legislation: Americans with Disabilities Act (Benchmark Books, 2011), 34-37

- ^ The Effectiveness of the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 (Public law 90-480): hearings before the Subcommittee on Investigations and Review of the Committee on Public Works and Transportation, House of Representatives, Ninety-fourth Congress, first session, October 7 and 20, 1975.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Design Bias Victims Grow Militant,” The Evening Star, Mar 13, 1976.

- ^ Gold, 34-37

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kuhn, Mary Ann, “Touring DC is an Added Handicap,” The Evening Star, Apr 20, 1978.

- ^ “Guide to Wheelchair Accessible Cities in the United States & Canada,” Wheelchair Travel.

![Capitol Crawl Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins wears a bandana as she crawls up the U.S. Capitol steps on her hands and knees. On her left is a man bending over and on her right a woman moves up the stairs on her back. All three protesters wear matching light blue shirts from the ADAPT organization. In front of them are media personnel with cameras and microphones recording the protest. [Photo Credit: Associated Press]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/Capitol%20Crawl%20AP%20Photo.jpg?itok=3SKhheG1)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)