This House, Undivided: Sarah Tracy’s Mount Vernon During the Civil War

It is the middle of September, 1861. Federal troops have occupied Alexandria and are in the process of confiscating enemy property. Through the upheaval rides a quiet, dark-haired woman with a shy but resolute presence. She has come from the countryside in a little wagon usually filled with home-grown cabbages. Today, as she travels to the nation’s capital, she has a basket of eggs beside her.

Sentries pause to examine her pass. Soldiers nod politely to the little lady. What they do not suspect is that beneath her eggs, she is delivering thousands of dollars in contraband bills and bonds through their lines to a DC banker. Between Alexandria and Washington, she passes nearly 75,000 troops.1 No one stops her.

The woman in this story is Sarah Tracy, and she was not a spy, but a secretary from New York. The money belonged to George Washington’s great-grandnephew, John Augustine Washington III, part of $200,000 paid to him by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association to purchase the first president’s estate. To ensure the safety of this massive investment the MVLA had made for the protection of George Washington’s home and history, Tracy was smuggling the money to a trusted banker in the capital. Of course, escapades of espionage were hardly in the job description when Tracy accepted her secretarial position in America’s first fledgling historical preservation society.

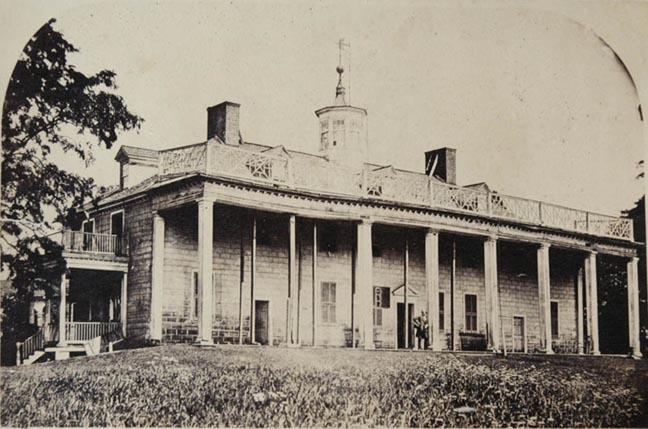

Tracy arrived at Mount Vernon in 1860 on the heels of Ann Pamela Cunningham, the MVLA’s regent. The Association had just acquired the property—badly in need of repair and renovation—and it was the culmination of years of work for an ecstatic Cunningham. But just as she was rolling up her sleeves, word came from South Carolina: she must return home to manage the family plantation.2 She left her distant cousin, Upton Herbert, and her secretary, Tracy, to watch over Mount Vernon.

Thus, Sarah Tracy found herself in rural Virginia, suddenly responsible for fixing and furnishing a 150-year-old national treasure. She was understandably apprehensive about her ability to do so.

Directions came in minute detail by letter from Cunningham. Tracy’s first job was to furnish the empty mansion: “I have been all day buying,” she wrote back. “I was frightened at the idea of daring to choose carpet and oilcloth for Mount Vernon, but I did the best I could.”3

Little did she know that her future problems would dwarf any concerns about carpet patterns. Only months later, Sarah Tracy would find Mount Vernon trapped between Union and Confederate lines: an island harboring an icon of American history, and somehow, she would have to shelter it from the storm.

Once news of war came, no one quite knew what to expect. On its perch over the Potomac, close to the Union and Confederate capitals, Mount Vernon was in grave danger of becoming a battleground, and the MVLA staff were too few to guard it on their own. Letters from Ann Cunningham came with rapid instructions. She feared that troops arriving to Mount Vernon by ferry might be induced to take “forcible possession” of the mansion and suggested closing the dock, but before any action could be taken it was seized to become a troop transport.4 At her urging, Tracy ventured out to both Union and Confederate commanders to assure Mount Vernon’s neutrality as a tribute George Washington and to the American women who had rescued his home. No troops would be placed there “under any plea whatsoever,” General Winfield Scott promised her, even though this was an arrangement that would need constant reaffirmation during the war.5

But even as she fretted in South Carolina, Ann Cunningham could think of no better protection for Mount Vernon than Sarah Tracy herself. Writing in 1864, Tracy would recall the Regent’s instructions to remain where she was: what Mount Vernon needed most to “insure respect” from both sides was “the presence of a lady.”6

The presence of a lady, however, didn’t keep other realities from coming. Communications broke down: worried about the suspicion her South Carolina address might arouse, Cunningham stopped writing directly to Tracy.7 With the roads blocked by soldiers, the ferry seized, and landings eventually banned on the Virginia bank of the Potomac, revenue disappeared. Restoration slowed and workmen had to be laid off. By the end of 1861, there was only Tracy, her chaperone, the superintendent Upton Herbert, and a few free Black employees.8

[Source: George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon]

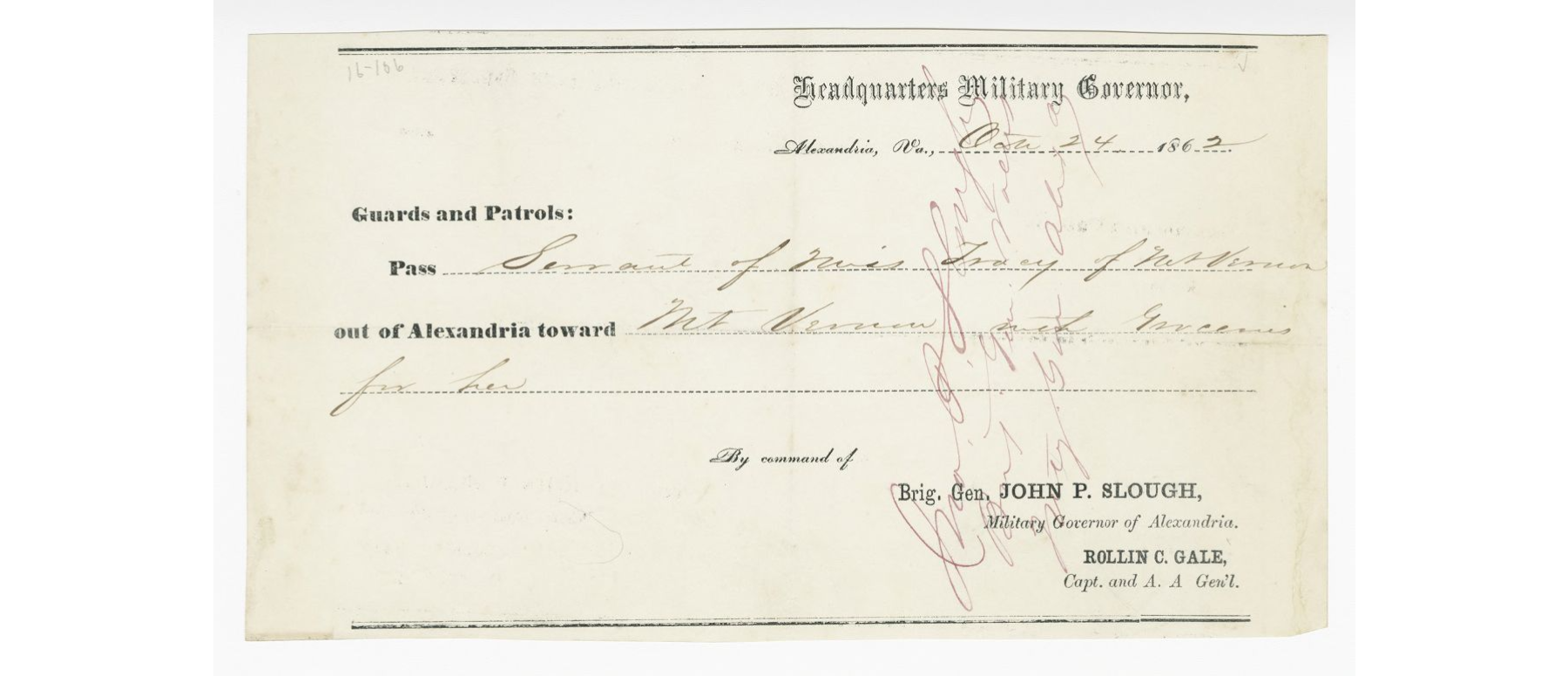

But if Mount Vernon occupied an ill-defined confluence where North met South and war met peace, its staff were uniquely equipped to navigate it. Beyond receiving the consideration afforded to ladies, Sarah was a Northerner and could obtain passes to Alexandria and Washington. Upton Herbert was a native Virginian with brothers fighting in the Confederate Army.9 While this barred him from Alexandria, it gave him crucial rapport with Confederate officers. And the Black employees were locals with excellent knowledge of the countryside, which allowed them to maneuver around main roads rendered impassible by barricades.

Though no battles took place on the grounds, the dangers of war still lurked. Northern Virginia experienced a revolving door of regiments during the war, surrounding the mansion with inexperienced, skittish soldiers.10 The staff was also well within range of artillery. According to legend, the windows of the house rattled from cannon fire throughout the Battle of Bull Run.11 While that is unproven, Sarah Tracy certainly overheard the battle’s chaos: "At six o'clock in the morning, I was aroused by cannon… it ceased, recommenced, and continued till dark. The sun rose upon their fury, and went down upon their unquenched wrath."12

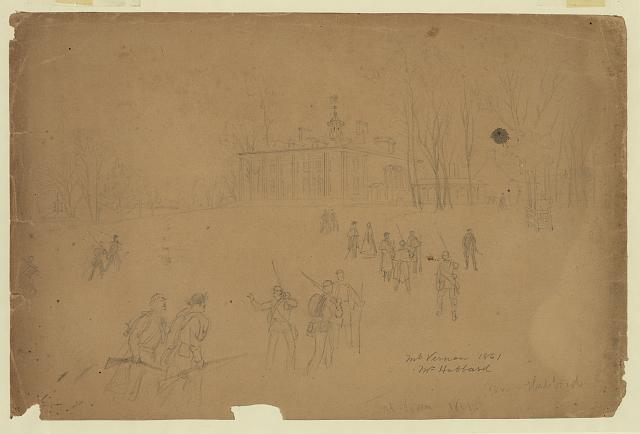

But even having battles within earshot, Sarah Tracy and her staff conserved Mount Vernon as a place of peace. Visitors continued to be welcomed throughout the war. For many soldiers, this was their first experience traveling, and Mount Vernon interested them. George Washington appealed to both sides: to the Confederates as a native son of Virginia and for Federal troops as the father of the Union.

Of course, they had to behave on the grounds. War was not to step foot in Mount Vernon. Weapons were not allowed on the property and had to be stacked outside. Not a military uniform was to be seen, Union or Confederate. Guests were expected, if they could, to pay the twenty-five cent admission fee. On Sundays, the mansion was closed.13

For the most part, reported Tracy, they obeyed: “Many of them come from a great distance and have never been here, and have no clothes but their uniforms. They borrow shawls and cover up their buttons and leave their arms outside the enclosures, and never come but two or three at a time. That is as much as can be asked of them." The admission fee was also negotiable: “. . . of course the soldiers plead poverty - many with truth."14

There were exceptions. Once several hundred men came at once and “trampled over everything.”15 One officer told Tracy that he would only lay down arms on the order of General Winfield Scott. In response, Tracy hiked up her skirts and marched to Alexandria, returning with a new written order from the general “to show any of his officers who do not wish to obey our regulations.”16

Incidents, however, were few and far between. Most soldiers came with respect towards the MVLA’s vision of Mount Vernon as a place above politics, meant for all Americans. They wrote home about their visits, drew sketches of the buildings and the Potomac, and left graffiti which remains there today. A private from Pennsylvania wrote in his diary that he would “never forget the sights of Mount Vernon.”17, 18

Early in the war, Tracy wrote to Cunningham that the war “completely unnerved” her.19 But the modest secretary was immovably brave when it came to protecting Mount Vernon. Not only did she run blockades and smuggle money out of occupied Alexandria without a second thought, but she also had a run-in with President Lincoln himself!

In late 1861, General Winfield Scott, an important collaborator of Tracy’s, was nearing the end of his career. The Army of the Potomac had just been formed and its new commander, George McClellan revoked the passes Scott had issued for Mount Vernon servants.20 This left only Sarah Tracy with the ability to pass through Union lines, a job she struggled with dutifully until her own pass was disputed by pickets. Without a pass there was no way to get to the Alexandria market, and as food began to dwindle, Tracy decided to “run the blockade” to Washington to uncover the source of the problem.

Once in Washington, Tracy went searching for someone who could help her. Friends suggested speaking to War Secretary Simon Cameron, Mrs. Lincoln, or General Scott, who had issued the passes. But at the army headquarters, she was told that there was “no power but the President” who could help her.

Naturally, Tracy’s next stop was President Lincoln’s door. What a sight that must have been: that demure little woman sitting down uninvited in the President’s office and asking if the United States Army would please let her through, for she is trying to take George Washington’s groceries to market.

But Lincoln “received [Sarah] very kindly” and immediately wrote to McClellan requesting him to “arrange the matter in the best way possible.” Upon receiving the note, General McClellan assured Tracy it was all a “grand mistake” and “offered to do anything he could” for the Mount Vernon staff. Armed with the President’s blessing, Tracy had a smooth time and came home with new, “rather more positive” passes.21 An abashed McClellan would send several boats stocked with provisions to Mount Vernon over the next few years.22

The situation at Mount Vernon was never stable, but the staff acclimated over time. Passes and skirmishes continued to be troublesome, and the war dragged on. But daily life was spent giving tours to soldiers, tending to the gardens and mansion, and trying to balance expenses with trickling revenue by selling food, hay, photographs, and souvenirs. Tracy kept up a long saga of attempting to reinstate the Mount Vernon ferry.23 They even made some progress on restoration: in 1865, they had not needed to make repairs for three years.24

The end of the war brought a surge of popularity to Mount Vernon. Union soldiers made their way home from the south, and many of them took advantage of the opportunity to visit. Tracy suddenly had “a rush of visits” from soldiers, and all of them were “crazy for flowers.”25 The staff scrambled to make bouquets and earned $300—nearly matching its entire revenue from the year before.

Regular contact finally resumed with an extremely relieved Ann Cunningham, who had not heard from her secretary directly in three years. Eager to be involved again, she wrote to ask if Tracy had been able to turn any profit.26 She didn’t have to worry; barely a year after the war’s end, Tracy was coming to “personally dread” the number of visitors pouring into Mount Vernon.27

For four years, Sarah Tracy, at the head of a tiny staff, had made Mount Vernon— “sacred ground” where the father of the United States had once walked—an island of peace and unity sitting on the burst seam of a nation. She was tired, but no plans were made to replace her. As Mount Vernon’s popularity picked up steam, she stayed on for another two years, making flower bouquets by hand and administrating restoration efforts. Finally, at an unusually short MVLA meeting in December, 1867, she handed in her resignation. On January 1st, she left Mount Vernon and seemingly, history itself.

While Ann Cunningham and Mount Vernon itself would go on to enjoy a brightening spotlight, Tracy’s name would fade softly away. She and Upton Herbert, who spent the war together at Mount Vernon, married in 1872. Their house burned in 1885, destroying a trunk with all her papers relating to her time safeguarding the first President’s house. Still, today’s flourishing Mount Vernon might not have survived without her. Its beautifully restored face stands testament to the little secretary who dutifully sheltered it as it was meant to be: a house undivided.

Footnotes

- 1 Muir, Dorothy. Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. Mount Vernon Ladies Assn of the, 1993. pp. 83.

- 2 Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Historical Sketch of Ann Pamela Cunningham ... Founder of the ... Association. Queensborough: Marion Press, 1911.

- 3 Muir, Dorothy Troth. Presence of a Lady: The Story of Mount Vernon During the Civil War. Mount Vernon Publishing Co., 1982. pp. 10.

- 4 Cunningham, Ann. Ann Pamela Cunningham to George W. Riggs, 1861 April 26. Letter. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 5 Muir, Dorothy. Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. Mount Vernon Ladies Assn of the, 1993. pp.53.

- 6 Muir, Dorothy. Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. Mount Vernon Ladies Assn of the, 1993. pp.109.

- 7 Cunningham, Ann. Ann Pamela Cunningham to Sarah Tracy, 1865 July 10. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 8

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “Mount Vernon during the Civil War.” Accessed 2023.

- 9

Smithsonian Associates. “Smithsonian Civil War Studies: Article.” Protecting Mount Vernon During the Civil War, 2009.

- 10 Johnson, Gerald W. Mount Vernon: The Story of a Shrine. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of Virginia, 1988. pp. 35.

- 11

Smithsonian Associates. “Smithsonian Civil War Studies: Article.” Protecting Mount Vernon During the Civil War, 2009.

- 12 Tracy, Sarah. Sarah Tracy to Margaret Comegys, 1861 July 22. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 13 Tracy, Sarah. Sarah Tracy to Captain Moses, 1862 March 7. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 14 Tracy, Sarah. Sarah Tracy to Ann Pamela Cunningham, 1861 May 2. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 15 Muir, Dorothy. Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. Mount Vernon Ladies Assn of the, 1993. pp. 96

- 16 Muir, Dorothy. Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. Mount Vernon Ladies Assn of the, 1993. pp. 67

- 17 James A. Minish, The Civil War Diary and Letters of Private James A. Minish, Co. “F,” 105th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, ed. M. L. Brown, Special Collections, Fred W. Smith Library for the Study of George Washington, Mount Vernon, VA.

- 18 Tracy and the staff even entertained some international visitors. In 1861, Tracy overheard Upton Herbert giving a tour to some men speaking French. She ran to open some Claret wine and offer it to the guests in French, which “opened their eyes and hearts.” The visitors turned out to be French minister Count Mercier and Prince Napoléon-Jérôme Bonaparte of Westphalia. As Tracy conversed with them in French, the prince told her he was “deeply impressed with the position of Mount Vernon… removed from the scenes of conflict, yet surrounded by them.” Wishing the MVLA the best of luck with its preservation of “sacred, neutral ground,” the prince returned to Washington. He left a carte de visite as a thank-you, addressed to his hostess, Miss Sarah Tracy. See: Presence of a Lady pp. 40 and Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. pp. 72

- 19

Smithsonian Associates. “Smithsonian Civil War Studies: Article.” Protecting Mount Vernon During the Civil War, 2009.

- 20 Muir, Dorothy Troth. Presence of a Lady: The Story of Mount Vernon During the Civil War. Mount Vernon Publishing Co., 1982. pp. 54

- 21 Tracy, Sarah. Sarah Tracy to Margaret Comegys, 1861 October 9. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 22

Smithsonian Associates. “Smithsonian Civil War Studies: Article.” Protecting Mount Vernon During the Civil War, 2009.

- 23 Tracy, Sarah. Sarah Tracy to Martha Mitchell, 1863, April 17. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 24 Tracy, Sarah. Sarah Tracy to Margaret Comegys, 1865 November 7. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 25 Muir, Dorothy. Mount Vernon: The Civil War Years. Mount Vernon Ladies Assn of the, 1993. pp. 116, 118.

- 26 Cunningham, Ann. Ann Pamela Cunningham to Sarah Tracy, 1865 July 10. From the George Washington Presidential Library, Early Records of the MVLA.

- 27 Muir, Dorothy Troth. Presence of a Lady: The Story of Mount Vernon During the Civil War. Mount Vernon Publishing Co., 1982. pp. 83

![Newspaper advertisement for Ona Judge, runaway slave [Source: Encyclopedia Virginia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2024-05/Ona%20Judge%20-%20Runaway%20Ad.jpg?h=10a38b52&itok=0_-DEpCm)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)