D.C.'s Prehistoric Fab Five: The Greatest Extinct Creatures that Roamed the DMV

For many, Washington D.C.’s history began in 1791, the year of the city’s founding. Others may harken farther back to the 17th century, when the Piscataway Native Americans inhabited the region.1 But have you ever thought what D.C. was like in a bygone era, when it was an actual (rather than a metaphorical) swamp, and the dinosaurs were reptilian instead of human? It can be forgotten that the land before D.C. was always a place with its own life or death struggles and dramas that can make the capital’s political chaos seem tame in comparison. We may not have been around to admire them (or run from them), but Washingtonians should take pride that some of the most spectacular animals from prehistory roamed our very own backyards. From giant dinosaurs to a shark that makes Jaws look like a minnow, we’ve selected five of our favorite prehistoric D.C. residents.

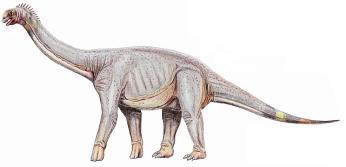

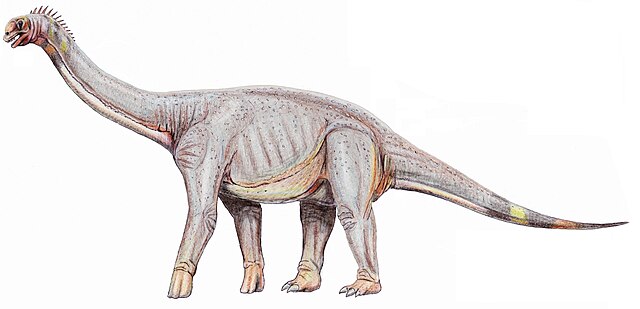

1. Astrodon

When It Lived: 112 to 110 million years ago, the Cretaceous period.2

In 1858 two fossilized teeth were found near Muirkirk, Maryland, becoming one of the earliest dinosaur discoveries in the United States. In 1942 the lower half of a monstrous thigh bone was dug up on the west side of First Street N.W. south of Channing Street. Although fragmentary, these fossils were determined to be from the same type of animal, a plant-eating dinosaur. The thigh bone fragment was only eleven inches long, but it would have been four feet long in life, and supported an animal that would have spanned 60 feet from head to tail and tipped the scales at a walloping 20 tons. More complete fossils discovered later in the aptly named Dinosaur Park in Laurel, Maryland confirm that the giant was Astrodon johnstoni.3 Astrodon was from the same family of dinosaurs as Brontosaurus, called the sauropods.

The argument over whether D.C. was built over a swamp has pretty much been debunked4 , but if you time traveled to the Early Cretaceous period, you’d realize those myth-spreaders were technically right, if off by 100 million years. Early Cretaceous D.C. resembled the Louisiana bayous and Gulf Coast, with humidity and vegetation that were perfect for giant plant-eating dinosaurs.5 For Astrodon, it would have been like living in a giant salad. A long neck and small head allowed this dinosaur to browse from treetops like a giraffe. An enormous potbelly held the hundreds of feet of intestine necessary to digest the massive quantities of plant matter that fueled this titanic compost machine. The farts would have been legendary.6

2. Acrocanthosaurus

When It Lived: 115 to 100 million years ago, the Cretaceous period.

Not even giant size or atomic farts could deter Astrodon’s nemesis. Thanks to teeth from Dinosaur Park, Maryland, we know that a giant carnivore held the title of apex predator in the D.C. bayous. Acrocanthosaurus may not have been as big as T.rex, but it still weighed a terrifying seven tons, stood 13 feet tall, and reached 38 feet long. It vaguely looked like T.rex, but what differentiated it the most was a ridge of muscle that extended along its back, giving the dinosaur its name.7 Acrocanthosaurus roughly translates to “high-spined lizard” from Greek.8 Acrocanthosaurus versus Astrodon would have been a monster battle to rival Godzilla versus King Kong. Even though Astrodon didn’t have the teeth and claws of its attacker, it still could have put up a formidable defense with its long muscular tail, and stomping, tree trunk-like legs. With strong clawed hands to put T.rex’s wimpy forearms to even further shame, Acrocanthosaurus would latch onto Astrodon, while its jaws inflicted horrendous bite wounds to the neck, legs and abdomen. Astrodon would eventually die of shock or blood loss.9

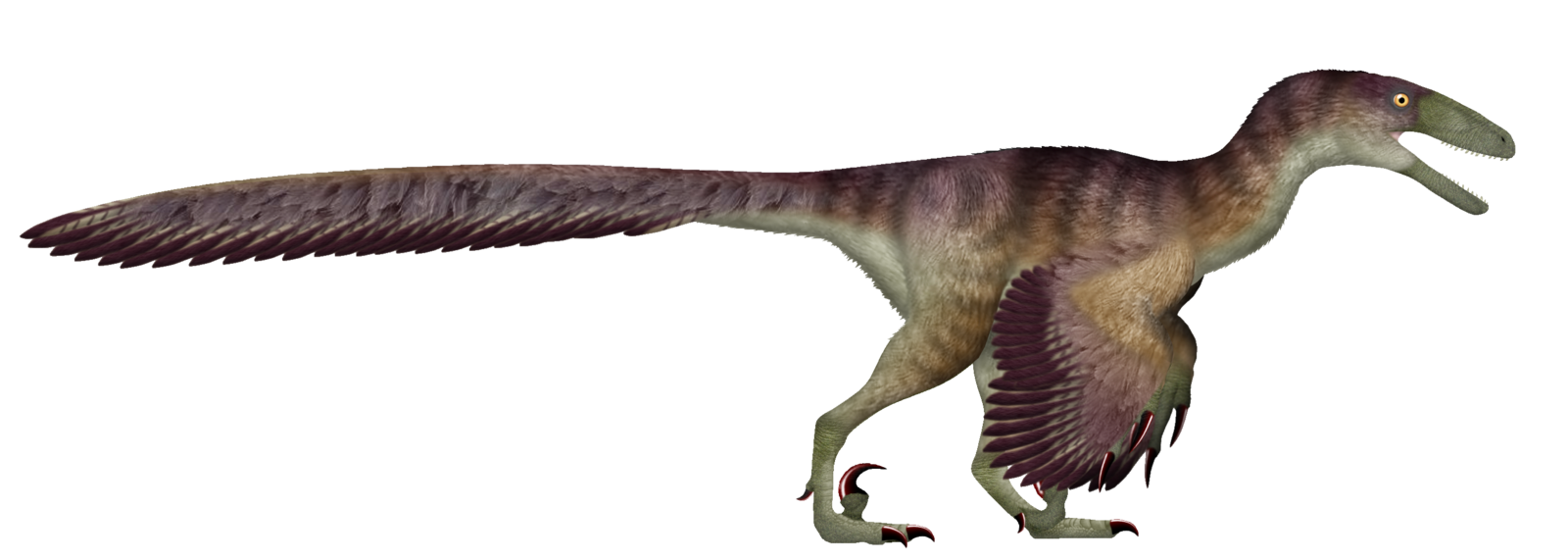

3. Deinonychus

When It Lived: 115 to 108 million years ago, the Cretaceous period.10

While Astrodon and Acrocanthosaurus duked it out, a smaller predator would have been watching from the shadows. Deinonychus was a feathered meat-eating dinosaur from the same group as the iconic Velociraptor of Jurassic Park fame, nicknamed “the raptors”. In fact, Deinonychus was the basis for the novel’s fictionalized Velociraptors, with the name changed because let’s be honest, you probably don’t know how to pronounce Deinonychus.11 This raptor was smaller and looked more like a bird than the scaly snake-eyed killers of Spielberg’s movie, but don’t let size and feathers fool you. This three meter long, 160-pound murder chicken still had the enormous sickle-shaped claws of its cinematic counterpart.12

Like with Acrocanthosaurus, only a few teeth from Maryland suggest that Deinonychus lived in D.C.. But thankfully for paleontologists, teeth are the most useful fossils they can find to confirm an animal’s identity, because of how much teeth can tell them about size, diet, and lifestyle. It’s possible that they could belong to some other dinosaur, though. Fossils are notoriously rare in the eastern half of North America, because of the gradual erosion of sediment into the Atlantic Ocean, compared to the fossil-rich deposits in the West.13

While no concrete evidence has emerged yet, fossils from Oklahoma of six Deinonychus that died together around a prey dinosaur, suggest that this raptor may have hunted in packs.14 What supports the possibility of Deinonychus’s residence in D.C. are suspected Maryland fossils of its favorite comfort food: Tenontosaurus. This 21 foot-long, one-ton herbivore15 had a well-documented predator-prey relationship with Deinonychus, like with the Oklahoma discovery. Unfortunately for Tenontosaurus, it may have also been on the menu for Acrocanthosaurus. Remarkably, D.C. during the Early Cretaceous was a showcase for how wide-ranging these four dinosaurs were, because all of them were spread over North America from as far west as Montana.16

4. Amphicyon, the Bear Dog

When It Lived: 23 to 5 million years ago, the Miocene epoch.17

The dinosaurs couldn’t rule the capital forever. We have a certain big rock from space to thank for the dinosaurs relinquishing power to a younger, furrier generation. 16 million years ago, it was the middle of the Miocene epoch. Mammals had come to dominate the globe and were flourishing from pole to pole. Many of them would have looked familiar to human eyes, but if your time-traveling self stood in D.C. and thought you’d be safe, meet the bear dog.

The name might elicit images of a mythical chimera, but the truth is that your imagination is pretty spot-on. Scientifically going by Amphicyon, the bear dog was neither a bear nor a dog but looked like a cross between the two. Imagine a giant wolf with the robust stockiness of a grizzly bear, along with a cat-like tail and paws thrown in for good measure. Bear dogs were one of the largest land mammal carnivores of all time. Some species were no bigger than cats, but the largest could have reached six feet long and 1,700 pounds in weight.18 The polar bear is the only living predatory land mammal that could rival the biggest bear dogs in size.19

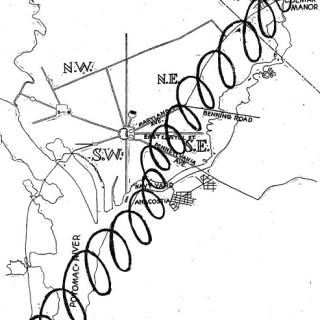

To understand the life of Miocene D.C., we must travel to Calvert Cliffs State Park, which overlooks Chesapeake Bay from Maryland’s Calvert Peninsula. This paleontological treasure trove preserves fossils of over 600 Miocene species in its cliffs, which can be collected by scientists and amateur fossil collectors alike, thanks to water erosion that cuts sediment from the cliffs and washes up fossils on the park’s sandy beaches.20 Among those fossils are skull fragments of an undetermined species of bear dog discovered in 1976.21 It’s surprising that the bear dog was even found in Calvert Cliffs at all, because this region, including D.C., was underwater during much of the Miocene, thanks to higher global sea levels. This map shows what North America looked like 20 million years ago, during the Early Miocene.22 But how did a land animal end up preserved in marine rocks? The coast was as far back as Richmond, Virginia, and was likely fed by rivers, streams, and swamps. Floods and high tides could have swept land animal carcasses out to sea, where they were rapidly buried by sediment on the seafloor and became fossils.23

Land animal fossils at Calvert Cliffs are rare, but what scientists do find offer tantalizing clues to what may have drawn bear dogs to prowl the coast near D.C.. Teeth and jaws from peccaries (called javelinas in the American Southwest) show up from time to time.24 Bear dogs may have hunted peccaries with bone-breaking swipes by lion-like paws and crushing bites to the throat.25 Thankfully, the bear dogs went extinct before our human ancestors ever had to worry about encountering one, with the last bear dog roaming the earth around five million years ago.26

5. Megalodon

When It Lived: 23 to 3.6 million years ago, from the Miocene to the Pliocene epochs.27

While the bear dog ruled the land near D.C. circa 16 million years ago, something infinitely more terrifying ruled the water.

Megalodon was not only the largest shark ever, but one of if not the largest predators in Earth’s history.28 This leviathan reached an estimated 49 to 66 feet in length and weighed 50 tons, about as big as a sperm whale. By comparison, a modern great white shark can only reach a maximum of 20 feet and two tons. Megalodon could have swallowed a great white whole. Although no complete skeleton has been found, it is known to have existed from thousands of fossilized teeth collected from around the world, including the ever-dutiful Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. Megalodon teeth are the Holy Grail for fossil hunters who scour the beaches near Calvert Cliffs, which was a warm shallow sea brimming with an astonishing diversity of marine life. From whale bones to swordfish skulls, paleontologists and fossil hunters alike are often rewarded for their search efforts.29 You might even get lucky and find a seven-inch Meg tooth yourself.

Unlike the biggest fish alive today, the gentle plankton-eating whale shark, Megalodon was a voracious predator. Large animals like sea turtles and dolphins were on the menu, but whales were a delicacy, with their enormous size and rich blubber. Tooth marks have been found on whale bones. Megalodon may have hunted by ramming prey, counting on its huge girth to incapacitate a whale long enough to carve into it with seven-inch chompers capable of delivering the strongest bite force of any animal in history.30, 31

Fortunately for us, Megalodon disappeared roughly 3.6 million years ago. And yes, despite what Shark Week “documentaries” and Jason Statham movies claim, Megalodon is definitely extinct. The identity of the culprit has been elusive, but the cause of Megalodon’s extinction was likely a combination of factors, including cooling global temperatures, declining whale diversity and competition with other predators, including prehistoric sperm whales and modern great white sharks. Too big and too specialized, Megalodon withered away while more-adaptable predators survived.32

D.C. may not celebrate its prehistory as jubilantly as some states do (we see you, Utah), but with such incredible creatures that once called this region home, maybe it one day will. There is plenty of history to be learned by visiting the DMV, but for a more complete understanding, we should know its prehistory as well. There are still many stories to be discovered.

Footnotes

- 1

Humphrey, Robert L., and Mary Elizabeth Chambers. Ancient Washington: American Indian Cultures of the Potomac Valley. 6. GW Washington Studies. Accessed November 15, 2023.

- 2 Carpenter, Kenneth, and Virginia Tidwell. “Reassessment of the Early Cretaceous Sauropod Astrodon Johnsoni Leidy 1865 (Titanosauriformes),” 78–114, 2005.

- 3

Kranz, Peter M. “Dinosaurs of the District of Columbia.” Accessed November 11, 2023.

- 4

Hawkins, Don. “No, D.C. Isn’t Really Built on a Swamp - The Washington Post.” The Washington Post, August 29, 2014.

- 5

Frederickson, Joseph A., Thomas R. Lipka, and Richard L. Cifelli. “Faunal Composition and Paleoenvironment of the Arundel Clay (Potomac Formation; Early Cretaceous), Maryland, USA.” Palaeontologia Electronica 21, no. 2 (August 28, 2018): 1–24.

- 6

“Prehistoric: Washington, D.C.” Documentary. Prehistoric. Discovery Channel, January 16, 2010.

- 7

“Acrocanthosaurus Atokensis – Museum of the Red River.” Accessed November 16, 2023.

- 8

Stovall, J. Willis, and Wann Langston. “Acrocanthosaurus Atokensis, a New Genus and Species of Lower Cretaceous Theropoda from Oklahoma.” The American Midland Naturalist 43, no. 3 (1950): 696–728.

- 9 Thomas, David A., and James O. Farlow. “Tracking a Dinosaur Attack.” Scientific American 277, no. 6 (1997): 74–79.

- 10

“Deinonychus.” Accessed November 30, 2023.

- 11

Cummings, Mike. “Yale’s Legacy in ‘Jurassic World.’” YaleNews, June 18, 2015.

- 12

Paul, Gregory S. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World: A Complete Illustrated Guide. New York : Simon and Schuster, 1988.

- 13

“Where Dinosaurs Roamed - Fossils and Paleontology (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed December 1, 2023.

- 14

Roach, Brian, and Daniel Brinkman. “A Reevaluation of Cooperative Pack Hunting and Gregariousness in Deinonychus Antirrhopus and Other Nonavian Theropod Dinosaurs,” April 1, 2007.

- 15

“Dinosaurs of Maryland.” Accessed December 1, 2023.

- 16

Lipka, Thomas R. “Affinities of the Enigmatic Theropods of The ...,” 1998.

- 17

Hunt, Robert. “Intercontinental Migration of Large Mammalian Carnivores: Earliest Occurrence of the Old World Beardog Amphicyon (Carnivora, Amphicyonidae) in North America.” Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences: Faculty Pubications, January 1, 2003.

- 18

Hunt, Robert M. Small Oligocene Amphicyonids from North America (Paradaphoenus, Mammalia, Carnivora). Vol. no.3331 (2001). New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History, 2001.

- 19

Schmidt, Amanda. “Polar Bear Fact Sheet | Blog | Nature | PBS.” Nature, December 9, 2020.

- 20

Calvert Marine Museum. “Preserving Maryland’s Prehistoric Legacy.” Accessed November 1, 2023.

- 21

Institution, Smithsonian. “Amphicyon Sp Object Details.” Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Natural History, June 10, 2021. Smithsonian Institution.

- 22

“North America - Deep Time MapsTM,” June 9, 2017.

- 23

McLennan, Jeanne D. “Calvert Cliffs Fossils.” Maryland Geological Survey, 1973.

- 24

Kowinsky, Jayson. “Fossil Vertebrate Identification for Calvert Cliffs of Maryland.” Accessed November 14, 2023.

- 25

“Prehistoric: Washington, D.C.” Documentary. Prehistoric. Discovery Channel, January 16, 2010.

- 26

Amphicyonids: The Bear Dogs, 2022.

- 27

ScienceDaily. “Giant ‘megalodon’ Shark Extinct Earlier than Previously Thought.” Accessed November 30, 2023.

- 28

Perez, Victor J., Ronny M. Leder, and Teddy Badaut. “Body Length Estimation of Neogene Macrophagous Lamniform Sharks (Carcharodon and Otodus) Derived from Associated Fossil Dentitions.” Palaeontologia Electronica 24, no. 1 (March 2021): 1–28.

- 29

Calvert Marine Museum. “Preserving Maryland’s Prehistoric Legacy.” Accessed November 1, 2023.

- 30

Prothero, Donald R. The Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of Evolution. Columbia University Press, 2015.

- 31

“Prehistoric: Washington, D.C.” Documentary. Prehistoric. Discovery Channel, January 16, 2010.

- 32

Why Megalodon (Definitely) Went Extinct | Season 2 | Episode 7 | PBS. Eons. PBS, 2023.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)