Did the Underground Railroad Run Through Georgetown?

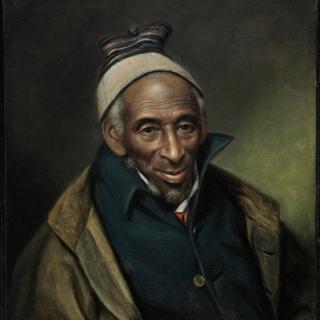

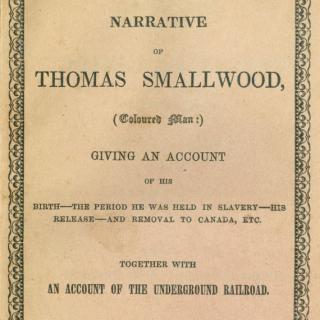

“Would-be runaways were instructed to arrive alone or in groups of no more than two to secret departure spots selected the night before. Those assembled headed for Pennsylvania, stopping at safe places along the way,” is what Thomas Smallwood, an ex-slave, wrote about his experiences as a “conductor” on Washington, D.C.’s Underground Railroad network between 1842 and 1844.1 Smallwood is also credited with giving the famous network its name.2

Slavery in Washington, D.C. began simultaneously with the city’s founding in 1790. Hundreds of enslaved people labored to build the White House, and more enslaved people worked in at least 8 of the 12 first presidential households.3 Slave markets surrounded the White House as well. In fact, the infamous Williams Slave Pen was on 7th Street in a yellow house, hidden behind trees and brick-wall, but visible from the Capitol Building. As a Congressman in the 1850s, Abraham Lincoln described the Slave Pen in stark terms: “A sort of negro-livery stable, where droves of negroes were collected, temporarily kept, and finally taken to Southern markets, precisely like droves of horses.”4

The Potomac River, and the location of the District between two slave states, Virginia and Maryland, was a major reason why slavery lasted in the nation's capital. According to historian Mary Beth Corrigan, “Washington offered dealers a convenient transportation nexus between the upper and Lower South, as the city connected to southern markets via waterways, overland roads, and later rail... Slaves stayed in crowded and dimly lit pens, including several near the Capitol.”5

Although slave markets were very prominent in the city, abolitionists and free blacks also held a strong and, in some cases, more secretive presence. Some of these abolitionists would help fight against the institution of slavery by participating in the Underground Railroad. This network spread across the nation where “conductors” and “station masters” helped runaways or “passengers” move from slave states to freedom in the north or Canada.6

Due to the secretive nature of the Underground Railroad, few records exist about specific sites, but one church that is thought to have been well-connected to the Railroad is Georgetown’s Mount Zion United Methodist Church — specifically the church burying ground located at 27th Street and Mill Road, NW.

The cemetery actually pre-dates Mount Zion UMC. It was founded by Montgomery Street Methodist Church in 1808, which bought the plot to bury white parishioners and their respective slaves. At the time Montgomery Street Methodist Church was one of few churches that included both white and black (enslaved and free) congregants, though worshippers were segregated.

In 1816, 125 black members established their own congregation known as Mount Zion United Methodist Church. Montgomery Street Methodist would continue to operate the cemetery, which was known as the Old Methodist Burying Ground, until 1879 when it was leased to Mount Zion.

On October 19, 1842, the Female Union Band Society, a benevolent society founded by African American and Native American women, bought the property along the western part of the Old Methodist Burying Ground for $250. The purpose of the land is outlined in their constitution, as each member would receive “$2 a week during sickness, as well as a grave and $20 for funeral expenses when deceased.”7 Since there was no visible boundary between the Old Methodist Burying Ground and the Female Union Band Society cemetery, the adjoining properties became known as Mount Zion Cemetery.

The environment provided advantages for runaway slaves. The graveyard is set on top of a plateau, built above Rock Creek, and has a ravine to the west and a swale to the east of it. A steep hill leads to the creek and was covered among tall trees. As Mount Zion historian Carter Bowman remarked to The Washington Times in 1998, “Back then, this was all woods here. It would have been easy for slaves to slip away and hide.”8

Within the cemetery is an 8x8 brick vault built into a hill. Built as a winter storage place for bodies which could not be buried until the spring thaw, the structure provided a sort of refuge for runaways.9 As historian Neville Waters told The Washington Post in 1991, “This was a safe place for the slaves because it was deep in the woods and covered over so that it was only visible from one side. And since bodies of the dead were kept here, nobody would have thought to look inside.”10

Water and food were discreetly left in the vault, which provided runaways an opportunity to rest before continuing their escape. After waiting until it was safe to move on, escaped slaves would apparently follow the hill down to Rock Creek, follow it to the Potomac River and, if all went well, make it to Pennsylvania.11

In April of 1862, slavery was finally outlawed through the DC Emancipation Act signed by Abraham Lincoln. Enslaved people became free and slave holders were compensated $300 for every enslaved person they owned. Mount Zion Church continued to be an anchor for Georgetown’s black community.

In 1879, the church signed a 99 year lease on the cemetery property, which remained active until the mid 20th century. By the 1950s, however, lack of funding had caused a decline. The cemetery became overgrown and stopped receiving visitors and burials.

Offers started coming in to move the graves to other cemeteries and redevelop the land for housing. As these proposals gained momentum, the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation intervened. Founded in 1970, to “develop programs that would assure the perpetual endurance of the contributions of blacks and other minorities to the American heritage,”12 ABC set out to “actively involve the black community in the fight to save Mount Zion Cemetery/Female Union Band Cemetery.”

In 1975, ABC successfully petitioned for the cemetery to be added to the National Register of Historic Places.13 In its recommendation letter, the group argued that the “history and that of the generation of Blacks both free and slaves interred therein uniquely convey the quality and thrust of Black life and evolving free Black culture in the District of Columbia from the earliest days of the city to the present. It is one of the few remaining physical reminders of the significant contributions of Black people to the development of Georgetown.”14 The nomination was officially granted less than two months later, on August 6, 1975.

In the decades since, various volunteer groups and individuals have worked to keep the cemetery properly maintained. Since 2005, the Black Georgetown Foundation (formerly known at the Mount-Zion Female Union Band Society Historic Park Foundation) has managed the preservation efforts. The historic vault, which likely housed escaped slaves as they traveled on the Underground Railroad, was restored between 2003 to 2007 with the help of donated funds.15

Despite the efforts, preserving and restoring the cemetery has continued to be an uphill fight. In 2012, the D.C. Preservation League listed the cemetery as one of the city's most endangered historic places.16 Activists have some optimism for the future, however. In 2023, the D.C. Council commemorated the Mount Zion-Female Union Band Society Cemetery’s 215th anniversary with a ceremonial resolution. The D.C. government also approved $1.6 million grant to upgrade storm drainage nearby.17

According to Black Georgetown Foundation executive director Lisa Fager, it bodes well for the future: “I am confident in my faith that this gesture is proof that we will no longer be neglected.”18

Footnotes

- 1 Hillary Russell, “Underground Railroad Activists in Washington, D.C.,” Washington History 13, no. 2 (Fall/Winter, 2001/2002): 31.

- 2

Olivia B. Waxman, "The Real Story Behind the Man Who Named the Underground Railroad,” Time, September 18, 2023.

- 3

“Index of Enslaved Individuals,” The White House Historical Association, accessed December 13, 2023.

- 4

Jeff Forret, “Presidents, Vice Presidents, and Washington's Most Notorious Slave Pen,” The White House Historical Association, November 26, 2019.

- 5 Mary Beth Corrigan, “Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.,” Washington History 13, no. 2 (Winter/Fall, 2001/2002): 5.

- 6 Russell, “Underground Railroad Activists,” 29.

- 7 "Mount Zion Cemetery Preservation Plan,” EHT Traceries, (April 2015): 10.

- 8 Bonnie Vanaman, “Tracking the Underground Railroad - Passage to freedom for runaway slaves was conducted by many in local area,” The Washington Times, February 26, 1998, M4.

- 9

Nicholas Fandos, ”At 2 Georgetown Cemeteries, History in Black and White,” The New York Times, October 20, 2016.

- 10

Avis Thomas-Lester, ”TRACKING HISTORY ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD,” Washington Post, February 25, 1991.

- 11 Fandos, ”At 2 Georgetown Cemeteries.”

- 12 Pauline Gaskins Mitchell, ”The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist Church and Mt. Zion Cemetery,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 51, (1984): 114.

- 13

”Mount Zion and Female Union Band Cemeteries,” National Park Service, accessed December 5, 2023.

- 14 Mitchell, ”The History of Mt. Zion,” 117.

- 15 “Mount Zion Cemetery Preservation Plan,” 22.

- 16 Fandos, ”At 2 Georgetown Cemeteries.”

- 17

Collins, Sam P. K. “D.C. Council Recognizes Black History Site in Georgetown.” The Washington Informer, February 21, 2023.

- 18 Collins, “D.C. Council Recognizes Black History Site in Georgetown.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)