Thomas Smallwood: Washington's Forgotten Abolitionist Hero Who Christened the Underground Railroad

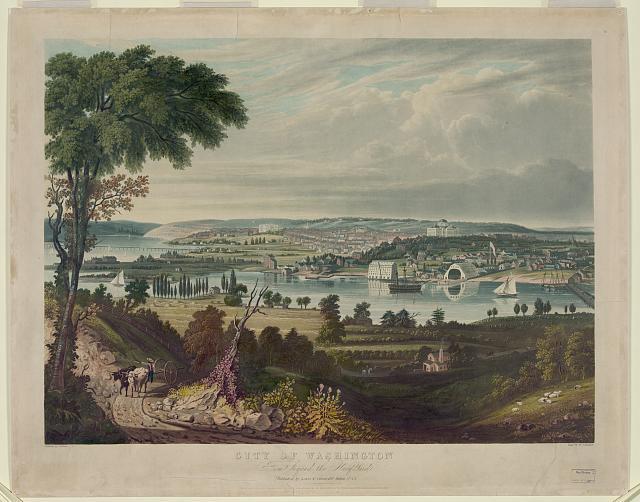

One evening in the early days of October 1843, a man named Thomas Smallwood met up with his wife, Elizabeth, and their five children in Baltimore, Maryland. He had spent the last thirteen hours walking all the way from Washington, D.C., having departed at 4 o’clock that morning, but there was no time for rest. The police were on Smallwood’s trail and the family wouldn’t be safe until they reached Canada.

What crime had this humble shoemaker and father committed to be pursued so eagerly by D.C. law enforcement?

He had helped 400 slaves escape north to freedom.

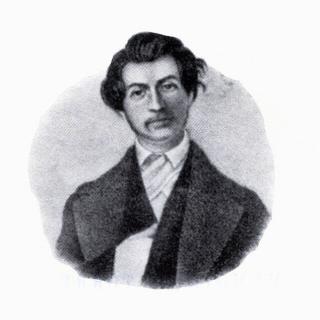

Thomas Smallwood was born into slavery in Prince George’s County, Maryland in 1801. As children, he and his sister were inherited by a widow who later married Reverend John B. Ferguson. Fortunately for the siblings, Ferguson “was no friend to slavery” and told the 15-year-old Smallwood that he would free him at age 30. Because of peculiarities of the law though, the minister would have to purchase young Thomas from his wife and her children of a previous marriage for $500, a sum which Smallwood would work to pay back in order to secure his freedom.1

To make the matter official, Reverend Ferguson took Smallwood down to the county courthouse and filed a record of his intention to free Smallwood and the terms under which he would do so. In the meantime, the Fergusons taught the young man to read, igniting a lifelong love of literature. Once he gained his freedom in 1830, Smallwood became a live-in servant for the family of a Scottish teacher name John McLeod. The McLeods encouraged him to continue his education. Smallwood later wrote that “for my advancement from two syllables to the little I now possess I owe a deep debt of gratitude to a family of that people who are proverbial for their love of learning and imparting it to others.”2

As he explored his new freedom, Smallwood got more involved with free black and activist communities. For several years, he was a believer in African colonization, a movement which promoted transplanting free African Americans to the new country of Liberia. He understood the Society’s goal to be “the entire abolition of slavery in the United States” but later determined “I was greviously [sic] deceived.” Instead, “The object and policy of that Society proved to be, under the mask of philanthropy, the draining off the free coloured population from among the slave population” so that they would not “contaminate” enslaved people “with a spirit of freedom, which made them uneasy in their bonds.”3

Once he discovered the true intentions behind African colonization, Smallwood began to actively look for other ways to help people still living in slavery. The opportunity to further expand his efforts came with the arrival in Washington of a white northern abolitionist named Charles Torrey.

Smallwood was intentional about keeping up with the news, especially as it related to abolitionism and the enslaved. One day, in 1842, he read about a young man who had been thrown in jail by a mob in Annapolis, Maryland for trying to report on a slaveholders convention for abolitionist newspapers. Torrey was released a few days later and, by a stroke of good fortune, was staying at the D.C. boardinghouse where Smallwood’s wife did the laundry. Elizabeth Smallwood arranged a meeting between the two men.

The formerly enslaved Smallwood and the Yale-educated Torrey did not have much in common. Even so, they hit it off from their first introduction. Torrey immediately filled Smallwood in on a plan to rescue a family of slaves belonging to the Secretary of the Navy. Secretary George E. Badger was planning to sell the family south, a move which would almost definitely separate them for good.4 While this particular escape never made it past the ideas stage (the mother of the enslaved family preferred to try to find the funds to buy their freedom), it was the start of something great. Smallwood and Torrey each saw in the other a partner who would benefit his own efforts exponentially, and so “their differences of social station, experience, style, and personality were set aside” in the pursuit of a common purpose.5

Over the next two years, the pair would repeatedly recruit up to 15 or 20 people at a time to escape. One of the men, usually Torrey, would rent a wagon and horses while Smallwood chose a meeting place. He never picked the same spot twice and always instructed people to arrive from different directions in sets of no more than two. Once everyone had gathered, they loaded themselves into the wagon and set off northward. Escapes in those numbers were unheard of and caused extreme frustration to local slaveholders and police. An Auxiliary Guard was formed, ostensibly to protect “the public property,”6 but really to catch fugitive slaves.

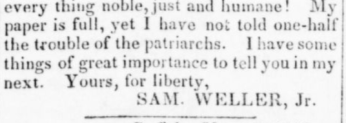

Even with the formation of the Guard, Torrey and Smallwood continued to spirit people away in the middle of the night. And they reveled in the vexation of the masters. Soon after they began working together, Smallwood put his impressive education to work writing letters to an abolitionist paper in Albany, New York called the Tocsin of Liberty (later, under Torrey’s ownership, the Albany Patriot). He wrote up-to-the-minute accounts of escapes using the real names of both escapees and their thwarted former owners, sometimes holding his missives for a week or two to be certain that his subjects had reached Canada. His tone was always one of condescending delight, mocking slaveholders for their loss under headlines such as “Property Become Man” and “More Fleeing From Happiness.”7 His letters “taunted, goaded, and belittled slaveholders in what amounted to psychological warfare.”8

Smallwood wrote under the pseudonym Samivel Weller, Jr., taken from the wildly popular “Pickwick Papers” by Charles Dickens. Even though his missives were published in Albany, he couldn’t risk revealing his identity; an arrest could mean being sold back into slavery. Besides, he always made sure a copy was sent to the slaveholders mentioned in each edition.

His letters often quoted runaway ads and addressed the details therein. David, a man who made it north in the summer of 1842, was advertised as having a stutter or lisp. According to Smallwood, “Liberty has had the wonderful effect of curing David’s impediment in his speech! – Mr. Shaw will find it hard even to recognize his voice again.”9

Sometimes he passed on messages from newly freed people:

“Henry Hawkins would like to have Sam inform Austin Scott, at Washington City, that he is well, and is delighted with Northern scenery and society, and hopes he may get along without his services in future. He wants him to send the editor of the Tocsin money enough to buy a new coat as the linen roundabout is nearly worn out, and it is coming on cold soon. This would only be a very small item in the amount of which Scott has robbed him of his services.”10

And he even pretended to sympathize with former masters:

“One word to your northern readers – Please Mr. Editor to suggest to them the propriety of raising a fund to defray the expense of advertising fugitives. It costs so much, and so little is got by it, that the poor poverty stricken slave-holders are getting unable to bear it.”11

Most famously, though, Thomas Smallwood’s Weller letters contain the first known record of the use of the term “Underground Railroad.” On August 10, 1842, he was going about his usual business of tearing down slaveholders when he coined the term which would be used forever after to refer to the systems and routes used by escaping slaves prior to Emancipation.

[I]t was your cruelty to him, that made him disappear by that same ‘under-ground rail-road or steam balloon’ about which one of your city constables was swearing so bitterly a few weeks ago, when complaining that the ‘d----d rascals’ got off so, and that no trace of them could be found! Very true!12

As a Black man, Smallwood was invisible to many of the white people in D.C., “powerless and irrelevant…beneath their notice, virtually invisible,” and he used that to observe them, gather information, and plan escapes.13 That was what he was doing when he overheard Constable Zell, a notorious slavecatcher, cursing about being unable to find the latest group of fugitives. Smallwood took Zell’s offhand remark about an “under-ground rail-road” and turned it into his own trademark. From then on, he used it consistently in his Sam Weller letters, calling himself “general agent of all the branches of the National Underground Railroad, Steam Packet, Canal and Foot-it Company” and writing that “they [slaveholders and -catchers] would give a plum to know where the under-ground Rail Road begins!”14

Though it took them awhile, authorities began to close in on Smallwood in 1843. The head of the Auxiliary Guard performed a search on his home (an escaped woman was there at the time, and was successfully hidden in a corn patch by Smallwood’s wife).15 Though nothing was found which provided grounds for arrest, Smallwood could tell it was time to get his family out of D.C. On his way to put his wife and children on a boat to Baltimore, the police accosted him again, this time blackmailing him, but he again avoided arrest. The encounter frightened him enough to cause him to forego his plan to take a train up to meet his family and he instead chose to walk, leaving as soon as the night watch ended.

The Smallwoods made it safely to Albany, then on to Toronto, where they began to establish themselves in a new life. Thomas Smallwood had always encouraged enslaved people not to stop until they reached Canada, believing that “The United States is the most hypocritical, guileful, and arrogant nation on the face of the earth. It is far preferable for coloured people to be subjects of any other nation on earth than that.”16 Escaped slaves would never be safe in the U.S. Now, he and his family joined some of those whom he had helped to send north over the past few years.

Within a few days of their arrival, four men that Smallwood had aided approached him, asking for help in getting their wives and children out of slavery. Smallwood agreed and got in touch with Torrey, who was in New York at the time, telling him what needed to happen. Torrey proposed that, while they were at it, they get a wagon and carry as many people away as possible. Just weeks after Smallwood’s own flight, they would make one more journey into the land of slavery together.

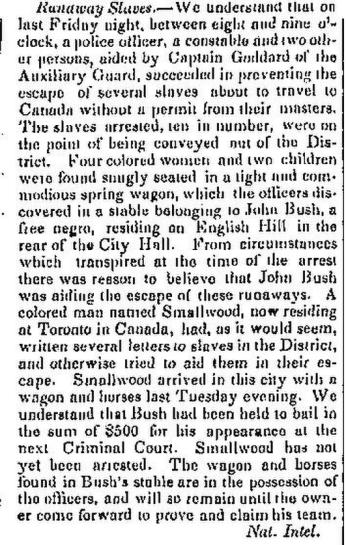

A local black man named John Bush allowed them to use his stable as a meeting place the night of the escape. Torrey and Smallwood parked the wagon inside and continued their preparations. After dark, people began to arrive. As usual, Smallwood had them arrive by ones and twos to avoid detection. Soon, ten refugees were settled into the wagon, waiting for the last handful of people so that they could set off. Before they could arrive however, Smallwood noticed a group of white men standing on the hillside outside of the stable. He sent Torrey to go investigate.

“He soon returned…trembling, saying they were constables, and requested me to try and get the people out of the waggon [sic].” But there wasn’t enough time. The constables were closing in. Smallwood had to make what was probably one of the hardest decisions of his life: “we had to make speed in making our own escape and leave the poor creatures to the mercy of the bloodhounds.”17

All of the would-be escapees were captured and arrested, along with John Bush, the owner of the stable. Most of the slaves would be sold south for their flight, while prosecutors attempted to have Bush executed by invoking an “old law of Maryland” which dictated hanging as the punishment for kidnapping a slave.18 Meanwhile, Torrey and Smallwood split up. Torrey stayed in town to try to get a lawyer for Bush and reclaim the wagon from the police. Smallwood made his way back to Canada, helping refugees along the way as he was able. (Bush’s case was later dismissed, though Torrey had hoped to take it to the Supreme Court and force the issue of abolition into the national spotlight.)

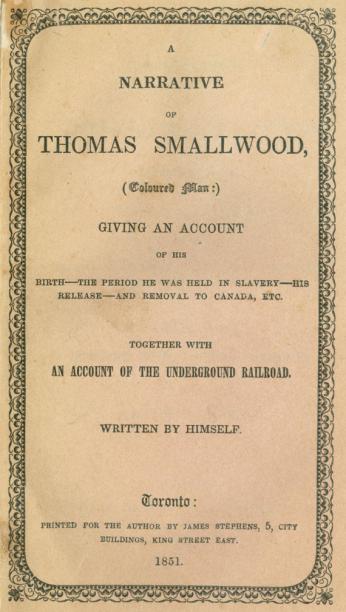

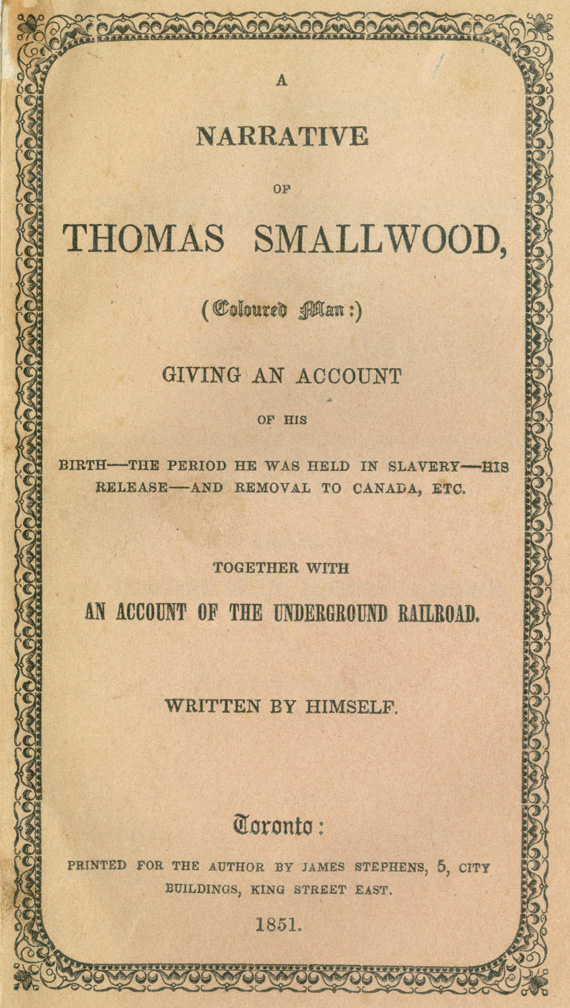

The failed escape in 1843 was the last time Thomas Smallwood would put himself directly in the line of fire in his quest to help enslaved people. However, he continued to do what he could from a distance. Smallwood became a leader in abolition societies and helped to organize conferences and collections to further the cause. He also wrote a memoir about his exploits.

Smallwood lived until 1883, building a home and a business in Toronto. About twenty years after his own flight north, he gave an interview to Samuel Gridley Howe of the American Freedman’s Inquiry Commission. Though he had written in his memoir that “I have never regretted one moment” moving to Canada, he told Howe “still I would rather go back to the old place, and intend to go back. Nothing but slavery and the wish to educate my children, in some part, brought me away from there.”19 He never made it back to the U.S.

Thomas Smallwood is not a household name and scholars have only recently begun researching his profound impact on slavery in Washington, D.C. (Flee North by Scott Shane, published in 2023, is the first book to discuss him as an activist and abolitionist in his own right). But over the course of his career, he personally changed the lives of about 400 former slaves,20 their families, and their descendants. And he did it all while laughing at the slave owners who he outsmarted and outwitted in the process.

Footnotes

- 1

Thomas Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), ed. Richard Almonte (Toronto: Mercury Press, 2000), 35.

- 2

Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), 36.

- 3

Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), 36.

- 4

Stanley Harrold, Subversives : Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 73, 77.

- 5

Scott Shane, Flee North: A Forgotten Hero and the Fight for Freedom in Slavery’s Borderland (New York, NY: Celadon Books, 2023), 55.

- 6

Charles T. Torrey, “Notes of Southern Travel by A Negro Stealer,”Albany Weekly Patriot, February 7, 1844.

- 7

Samivel Weller, Jr., “Property Become Man,”The Tocsin of Liberty, July 27, 1842; Samivel Weller, Jr., “More Fleeing From Happiness,”The Tocsin of Liberty, November 3, 1842.

- 8

Harrold, Subversives, 89–90.

- 9

Samivel Weller, Jr., “Runaway Property,”The Tocsin of Liberty, August 24, 1842.

- 10

“Twenty-Six Slaves in One Week,”The Tocsin of Liberty, September 21, 1842.

- 11

Samivel Weller, Jr., “Business in Washington, D.C.,”The Tocsin of Liberty, August 10, 1842.

- 12

Weller, "Business in Washington, D.C.”

- 13

Shane, Flee North, 131.

- 14

Shane, 297; Weller, “More Fleeing From Happiness.”

- 15

Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), 53–54.

- 16

Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), 65.

- 17

Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), 58.

- 18

Samivel Weller, Jr., “News from Washington: Arrest of John Bush!,”Albany Weekly Patriot, December 19, 1843.

- 19

Smallwood, A Narrative of Thomas Smallwood (Coloured Man), 56; Samuel Gridley Howe, Interviews of Black and White Residents of Canada West, 1863.

- 20

400 is an estimate made by Charles Torrey and one which scholars tend to believe given the quantity of people they aided at a time and the sheer number of trips north, though it’s difficult to come up with hard numbers when researching the escapes of enslaved people. Whether the figure is accurate or not, Smallwood’s impact was beyond significant. Charles T. Torrey, “Letter from Charles T. Torrey to Milton M. Fisher,” November 16, 1844.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)