Was D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War?

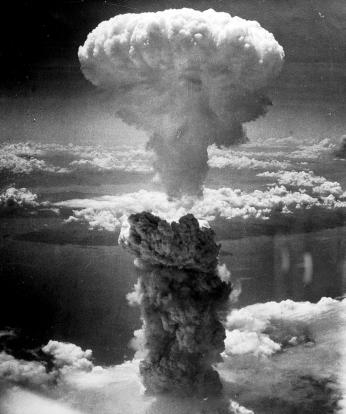

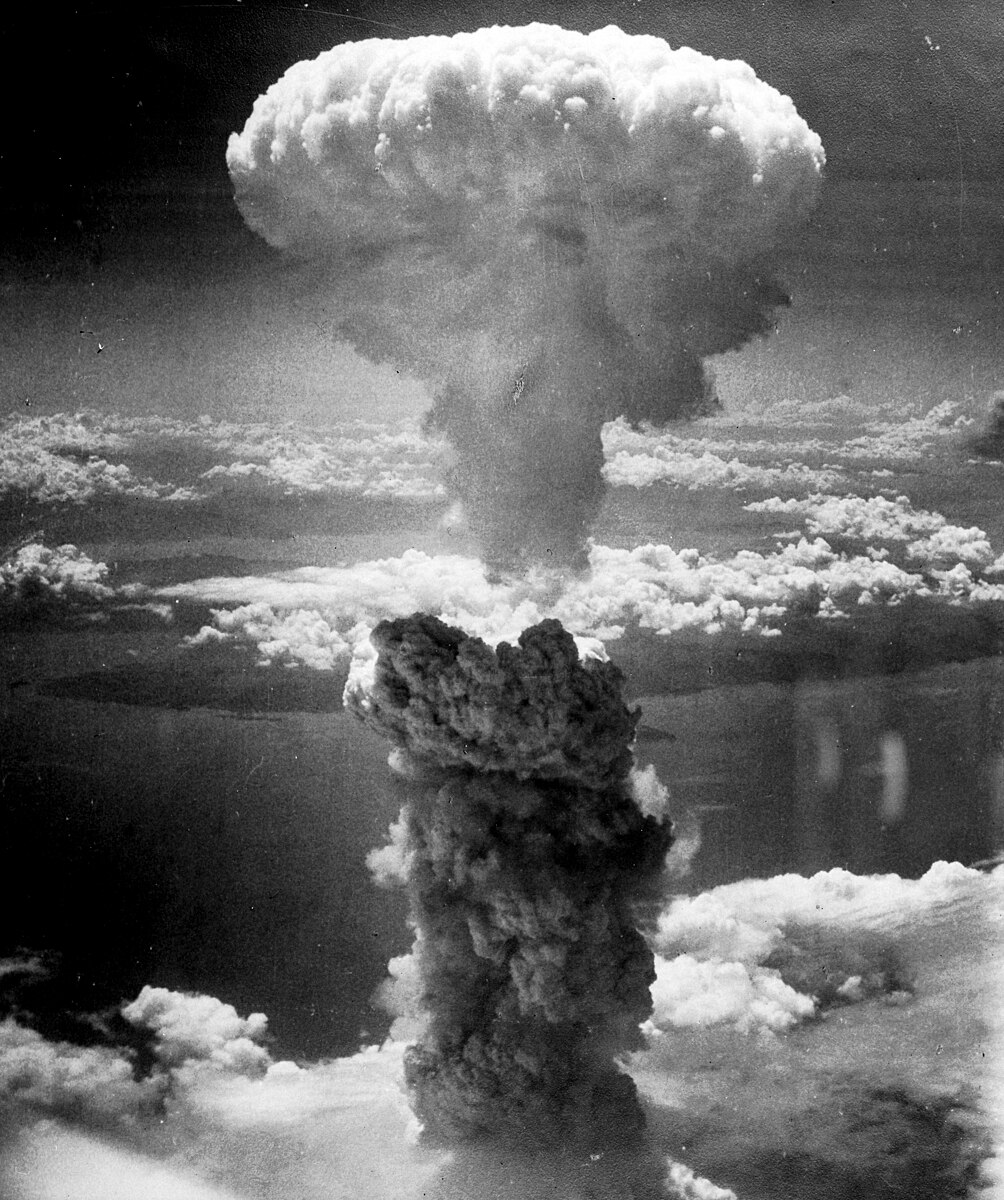

Thirty-two years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it is hard to imagine the pervasive fear of nuclear holocaust that permeated American society during the Cold War. The road to ruin would have entailed bellicose rhetoric, tactical escalation, and ultimately, decisions to launch missiles intended to wipe out entire countries. But that wasn’t the only threat. In the unlikely event of survival after a nuclear attack, humanity still would have been subject to nuclear fallout, a radioactive cloud of debris that threatened to rain down over any survivors even hundreds of miles away. Those contaminated would have contracted severe radiation sickness and likely would have suffered slow, agonizing deaths in a world of ash and ruin.1

As the Soviet Union’s chief rival in the Cold War, America’s cities, especially Washington, D.C., would have been primary targets. The federal government built hundreds of fallout shelters throughout D.C. to protect Washingtonians in the event of a nightmare scenario. However, few believed they would be effective.2

By 1961, the threat of nuclear war was intensifying. The crisis over the construction of the Berlin Wall showed that aggressions by nuclear powers could escalate rapidly. After years of building its nuclear arsenal, the federal government didn’t really have a strategy to ensure the public’s survival should the Soviets launch an all-out attack against the U.S..3 For average citizens, their first best line of defense was found in the Office of Civil Defense’s booklet, “The Family Fallout Shelter”, which contained instructions on how to build one.4 Children learned to duck and cover under their desks from the Bert the Turtle cartoon at school.5 A city evacuation plan was laid out for D.C. that required sirens and radio announcements to go off at least an hour before a nuclear strike. Could over 2 million people reasonably be expected to evacuate the District in an hour? That plan supposes there would be an hour’s warning.6 And where would everyone go? America’s civil defense strategy raised many doubts.

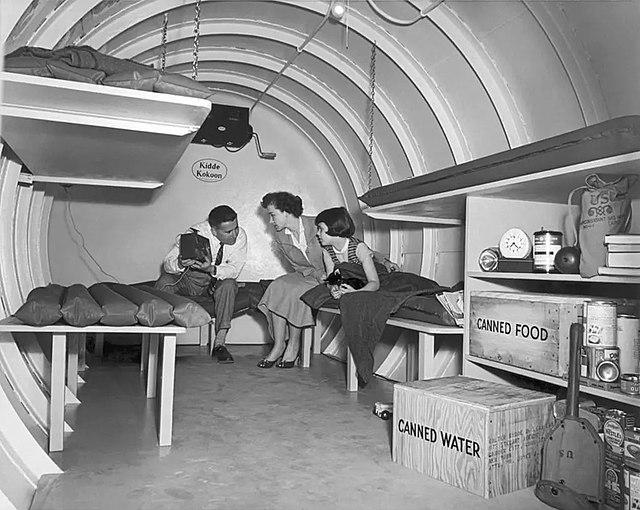

President John F. Kennedy agreed with the widely-held belief that fallout shelters were the most practical way to survive a nuclear attack. When addressing Congress on May 25, 1961, he recognized that while fallout shelters couldn’t save everyone, they offered “insurance we could never forgive ourselves for foregoing in the event of catastrophe.”7 Fallout shelters were meant to provide an enclosed space that could not only withstand a blast, but shield occupants from outside radioactive particles long enough for the radiation to decay to safe levels. Shelters would have to be properly ventilated and stocked with food, water, medicine, and sanitation equipment.8

In 1960, D.C. only had around 200 shelters built by private citizens.9 Clearly, with a population of 763,000 in just the District alone,10 there wasn’t enough space for everyone in D.C.’s private shelters, and no average citizen even knew about the top-secret government bunkers in West Virginia and Pennsylvania.11 To address this obvious shortfall, Kennedy called upon the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, to ensure “the survival of the American population in the event of nuclear attack on the United States.” The Office of Civil Defense (OCD) was created to achieve this goal. The OCD was preceded by the Federal Civil Defense Act in 1950, which divided the responsibility for civil defense between federal and state governments.12 Every region of the country already had civil defense offices, including the District of Columbia OCD, or DCD (a lot of acronyms, I know).13 Kennedy launched the National Fallout Shelter Survey in September 1961 to find spaces in buildings that could be designated as shelters and stocked with supplies. Congress appropriated $207 million in funds for the program. The survey was directed by the OCD with assistance from the Army Corps of Engineers and the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks. It was carried out by hundreds of architects and engineers trained in fallout shelter analysis.14

The OCD established minimum requirements for shelter spaces. Public shelters needed shielding from at least one-fortieth of the radiation released by a nuclear strike.15 They needed space and supplies for fifty people, and a minimum of 10 square feet to 500 cubic feet for each person, depending on the shelter’s ventilation. Surprisingly, many surveyed shelters were not underground, but in the core of buildings.16 Property owners with suitable spaces in their buildings could not be forced to commit their spaces to the shelter initiative. If they agreed, they would co-sign a Fallout Shelter License or Privilege form with the government, who would be responsible for the shelter’s stocking and upkeep. The property owner could revoke the license, but wouldn’t receive any compensation from the government for the loss of their space.17

Designated shelters were marked with the now iconic black-and-yellow fallout signs, and many were stocked with food, water, medicine, sanitation and radiation detection equipment.18 The food rations were mostly “All Purpose Survival Biscuits”; wheat wafers that were about as tasteless as they sound. “They’re good with a little bit of cheese on them with a martini on the side,” said a civil defense official, “but you wouldn’t want to eat them for a couple of weeks with nothing else.” Martinis were not provided by the government. All of a shelter’s food stocks were only meant to provide about 10,000 calories per person over two weeks.19 Toilets would have been empty water drums with rubber seats. There was no plumbing.20

By 1962, Washingtonians were growing wary of government efforts to provide adequate defense for their city. Citizens voiced their frustration. “I’m damned sore,” said building contractor Joseph Parry-Hill to The Washington Post in January. “It’s taken years for these defense people to even recognize the need for shelters.”21 The first public shelter had only opened on February 20 that year, at the Ambassador Hotel on 1412 K St. NW.22 Many citizens built and expanded their own expensive shelters. Businesswoman Marjorie Merriweather Post built five shelters for $20,000.23 Parry-Hill started a petition in his neighborhood to build a community shelter for a hundred people. “Private shelters are a selfish, immoral approach to the problem.” Parry said. His plan was rejected by the D.C. government, which decided that public shelters couldn’t be built by private citizens.24

Just five shelters were built and stocked by late October 1962, when the world arguably came closest to nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. All five shelters were built in downtown D.C., including one at Union Station. None could have survived just a one-megaton blast.25 You might think the situation in Cuba should have kicked things into higher gear, but only five more shelters were completed by that November.26 The majority of food stocks were still being produced or sat waiting in warehouses, due to a lack of storage space in shelters and a shortage of delivery trucks.27

Fortunately, the DCD began picking up steam by March 1963 thanks to a surge in funding and interest. More than half of the 1,301 eligible private and government buildings in the city were licensed as shelters and stocked with provisions.28 By April, D.C. had 45 completed shelters, the most of any municipality in the nation. Seven hundred black-and-yellow signs were scattered throughout the city by that summer.29 By June 1964, the city’s total shelter capacity surpassed 500,000 people with 928 shelters and were stocked with enough food and water for that number of people to survive two weeks.30 A thousand shelters were completed by March 1965. The shelters could be found in school basements, underground parking garages, boiler rooms, and tunnels underneath landmarks like Union Station and the Capitol. Not all shelters were built equal, with varying sizes, depths and designs depending on the buildings in which they had been constructed.31

Unlike the highly fortified underground lairs we sometimes see on TV, these shelters were cramped, claustrophobic spaces with no guarantee of adequate ventilation, unspoiled food stocks, or even accessibility in the event of nuclear disaster. Moreover, there was little defense against boredom or the psychological consequences of surviving a nuclear catastrophe. Even by 1960s standards, no one living in these shelters could claim they were riding out the apocalypse in comfort. Well, almost no one. If you wanted to live out your post-apocalyptic fantasy in style, your best option would have been the shelter underneath the National Geographic Headquarters. With a surge of funding and interest thanks to the Cuban Missile Crisis, this shelter included luxurious amenities like blankets, separate showers for men and women, toothpaste and diapers.32

By June 1965, the Community Shelter Plan Study for Washington, D.C. identified an astonishing 2.9 million potential shelter spaces in D.C.. With DCD estimates of 1.2 million to 1.4 million Washingtonians requiring shelters to survive a nuclear attack, that number of spaces was more than double the city’s need for shelters. But as much as they would have liked to, the DCD would never have been able to cram over a million Washingtonians into shelters when doomsday arrived. Seventy-three percent of those almost three million spaces were downtown, where only 23% of D.C.’s population lived. Residents of the suburbs and outskirts could almost certainly never reach a shelter in time before a detonation. The Community Shelter Plan Study foresaw the extremely high likelihood of mass deaths due to overcrowding and suffocation, caused by countless numbers of people cramming into shelters in certain areas.33

In total, 7,000 shelters were completed in D.C. out of the 2.9 million potential spaces, though only 500 were ever fully stocked.34 But just one year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, public apathy about nuclear war set in, despite the progress made by the National Fallout Shelter Program. By the end of the 1960s, spaces for 131 million people had been identified across the country, though only spaces for 46 million people were marked with fallout signs.35

In July 1972, a D.C. air raid siren test received an indifferent response from the public. A civil defense veteran summed up the public’s attitude. “You’ll find people who say, ‘There must have been a helluva fire someplace.’” After over 20 years of living with the threat of nuclear war, the public’s attention seemed to shift to other, more immediate events in the world. A period of détente saw tensions cool between the U.S. and Soviet Union, reducing national fear of nuclear war. Funding for the national shelter program declined in the early 1970s.36 The Office of Civil Defense was renamed the Office of Emergency Preparedness (OED) and pivoted towards combating natural disasters and riot control. The OED was dissolved in 1979, and its activities were transferred to FEMA, the country’s primary disaster response agency to the present day.37

In 1974, the shelter beneath Dupont Circle had twenty tons of wheat biscuits removed and sent to Bangladesh as humanitarian relief after severe flooding. But the supplies in most of the other shelters were rotting by the early 80s. Homeless people inhabited at least one shelter, making use of the wheat biscuits, water drum toilets, cots and mattresses. Most shelters were repurposed by building owners, and supplies were discarded.38

Fast forward to 2024. An estimated 1,624 shelters remain, some virtually untouched from their Cold War days.39 The blog District Fallout has a map of all of the locations. With the fear of nuclear holocaust, one big question remains. Would they have actually saved people? The government never enthusiastically claimed their shelters would save Americans. Many believed that the shelters were unlikely to survive a nuclear blast.40 Even if they did, as William Brownell, a civil defense consultant and nuclear survival expert said in 1982, “How are they going to get people out when the entire building has collapsed on top of all the exits?” Even at its 1962 peak, the National Fallout Shelter Program was never adequately funded to ensure the shelters were built and stocked properly. Brownell’s assessment of the program was grim. “The real number of fallout shelters is zero…. You put garbage in, and you get garbage out.”

The nuclear disarmament advocate Dr. Gerald F. Winfield compared a nuclear strike to the firebombing of Dresden, Germany in World War II. He thought that just a one-megaton bomb dropped on a city would suck all of the oxygen out of shelters and bake the occupants. The biggest Soviet nuclear bomb was 58 megatons. What kind of a world would any survivor face? Catastrophic climate effects like nuclear winter may have starved the rest of the world into famine.41 In assessing the government’s efforts to protect its citizens decades after the end of the Cold War, the National Fallout Shelter Program can be summed up as the federal government wanting proof that it was doing something to protect its civilians from the devastation caused by a nuclear war.42

Tragically, the fear of nuclear war feels closer today than perhaps at any other time since the Cold War. With about 12,500 nuclear weapons spread across nine countries, and nuclear powers like Russia, China and North Korea threatening US partners and allies, some believe the Doomsday Clock may be inching closer to midnight.43 The fallout shelter signs littered throughout D.C. may be dark reminders of the tension that gripped the city decades ago, but they should remind us of the apocalyptic future never more than a few miscalculations and a locked briefcase away. While there isn’t any current plan to revitalize the shelters,44 hopefully there will never be such a need.

Footnotes

- 1

Atomic Archive. “Radioactive Fallout.” Accessed February 15, 2024.

- 2 Krugler, David F. This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- 3

Irish, Adam, and Melissa Hopper. “Impetus and Impotence.” Blog. DISTRICT FALLOUT (blog), September 30, 2010.

- 4 The Family Fallout Shelter. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, 1959.

- 5

Duck And Cover (1951) Bert The Turtle. Social guidance film. Archer Productions, 1952.

- 6

Reporter, Morton Mintz Staff. “New Civil Defense Plan Maps D.C. Evacuation: Proposals Made.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), July 30, 1961, sec. City Life.

- 7

Address to Joint Session of Congress May 25, 1961 | JFK Library. CBS, 1961.

- 8 The Family Fallout Shelter. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, 1959.

- 9

Reporter, Carole Bowie Staff. “D.C. School Shelter Adequacy Reviewed.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), November 10, 1961, sec. City Life.

- 10

Corrigan, Mary Beth. “Guides: Washington, D.C., History Resources: Timeline.” Georgetown University Library, November 17, 2023.

- 11

The Center for Land Use Interpretation. “The Lay of the Land: Bunkers beyond the Beltway: The Federal Government Back-Up System,” Spring 2002.

- 12

Durkee, William P. “Civil Defense 1965.” Department of Defense - Office of Civil Defense, 1965.

- 13

McNamara, Robert S. “1962 Annual Report of the Office of Civil Defense.” Government. Washington, D.C., April 8, 2021.

- 14

Reporter, Morton Mintz Staff. “New Civil Defense Plan Maps D.C. Evacuation: Proposals Made.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), July 30, 1961, sec. City Life.

- 15 “Community Shelter Plan Study for Washington, DC, Volume I: Plan Study and Recommendations.” Washington, D.C., United States: Office of Civil Defense, June 1965.

- 16

Durkee, William P. “Civil Defense 1965.” Department of Defense - Office of Civil Defense, 1965.

- 17

“Fallout Shelter License Form and Example.” The Corps of Engineers and Bureau of Yards and Docks, 1962.

- 18

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “D.C. Leads In Number of CD Shelters - ProQuest.” April 2, 1963.

- 19

Writer, Lawrence Feinberg Washington Post Staff. “Bangladesh Hungry to Get Biscuits Kept in CD Tunnel: Bangladesh to Get D.C. CD Biscuits.” The Washington Post (1974-), September 14, 1974, sec. SPORTS Local News Obituaries Classified.

- 20

Civil Defense Museum. “Civil Defense Museum-Community Fallout Shelter Supplies - Sanitation Kits,” 2011.

- 21

The Washington Post, Times Herald. “D.C. Rejects 100-Person Shelter Plan - ProQuest.” January 14, 1962.

- 22

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “Ambassador Becomes District’s First Shelter.” February 21, 1962, sec. City Life.

- 23 Krugler, David F. This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- 24

The Washington Post, Times Herald. “D.C. Rejects 100-Person Shelter Plan - ProQuest.” January 14, 1962.

- 25

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “Federal CD Officials Speed Drive To Line Up Fallout Shelter Space: No New Program.” October 25, 1962.

- 26

DISTRICT FALLOUT. “Establishment of D.C. Fallout Shelters,” September 30, 2010.

- 27

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “10 Shelters Get Food Stocks-- Only 990 to Go.” November 7, 1962, sec. City Life.

- 28

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “673 Buildings Licensed As Fallout Shelters Here: Anti-Rabies Clinics.” March 28, 1963, sec. City Life.

- 29

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “CD Head Fends Questions On Closed Dupont Shelter.” June 1, 1963.

- 30

The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973). “D.C. Has 928 A-Shelters.” June 30, 1964, sec. Comics.

- 31 Krugler, David F. This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- 32

Anderson, Ward. “No Good Place to Hide.” Washington Post, December 25, 2023.

- 33 “Community Shelter Plan Study for Washington, DC, Volume I: Plan Study and Recommendations.” Washington, D.C., United States: Office of Civil Defense, June 1965.

- 34

Anderson, Ward. “No Good Place to Hide.” Washington Post, December 25, 2023.

- 35 Krugler, David F. This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- 36

Writer, David R. Boldt Washington Post Staff. “Public Is Indifferent to Tests of Air Raid Sirens.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), July 16, 1972, sec. METRO Local News Obituaries Classified.

- 37 Krugler, David F. This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- 38

Writer, Lawrence Feinberg Washington Post Staff. “Bangladesh Hungry to Get Biscuits Kept in CD Tunnel: Bangladesh to Get D.C. CD Biscuits.” The Washington Post (1974-), September 14, 1974, sec. SPORTS Local News Obituaries Classified.

- 39

Boschetti, Sianna. “The Past, Present and Future of the District’s Fallout Shelters.” The Wash, November 17, 2019.

- 40

Irish, Adam, and Melissa Hopper. “DISTRICT FALLOUT.” Blog. DISTRICT FALLOUT (blog), 2010.

- 41

Anderson, Ward. “No Good Place to Hide.” Washington Post, December 25, 2023.

- 42

Irish, Adam, and Melissa Hopper. “DISTRICT FALLOUT.” Blog. DISTRICT FALLOUT (blog), 2010.

- 43

Kristensen, Hans M., Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Kate Kohn. “Status of World Nuclear Forces.” Federation of American Scientists. Accessed February 16, 2024.

- 44

Irish, Adam, and Melissa Hopper. “DISTRICT FALLOUT.” Blog. DISTRICT FALLOUT (blog), 2010.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)