The Enigmatic Poe Toaster of Baltimore

"By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes!" It is the middle of the night in Baltimore on the street outside of Westminster Hall, a deconsecrated church and burial ground. The temperature has plunged, but a small knot of people wait in the cold outside the cemetery. As the small hours of morning creep by, they finally see it: a figure all in black, creeping between the gravestones in the Gothic shadow of the church. He makes his way to Edgar Allan Poe’s grave and somberly places three roses and a half-empty bottle of cognac on the white memorial. Without a word, or any acknowledgement of his audience, he disappears back into the night.

This is the Poe Toaster, a Baltimore tradition of 80 years paying homage to a poet the city calls its own.

Edgar Allan Poe was a drifter during his lifetime. Cities as varied as Boston, Richmond, Sullivan’s Island, Philadelphia and New York City can each lay claim to a bit of the poet’s history. Poe came only briefly to Baltimore several times, penning minor works and marrying his wife (and cousin) in the city.1 Baltimore’s best claim to Poe is fittingly brief and morbid: in October 1849, the poet was found bedraggled and delirious on the street in the Fourth Ward. Taken to Washington College Hospital, he died of causes unknown and was buried without a headstone at a quiet, underattended funeral by Westminster Hall.

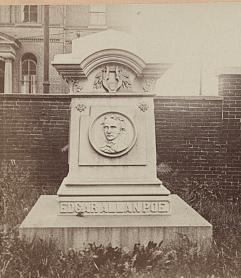

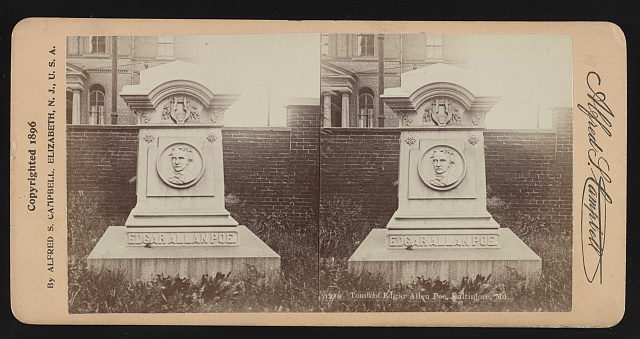

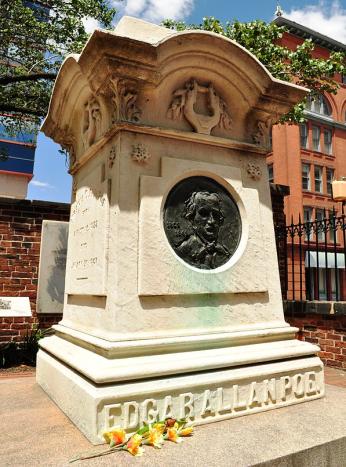

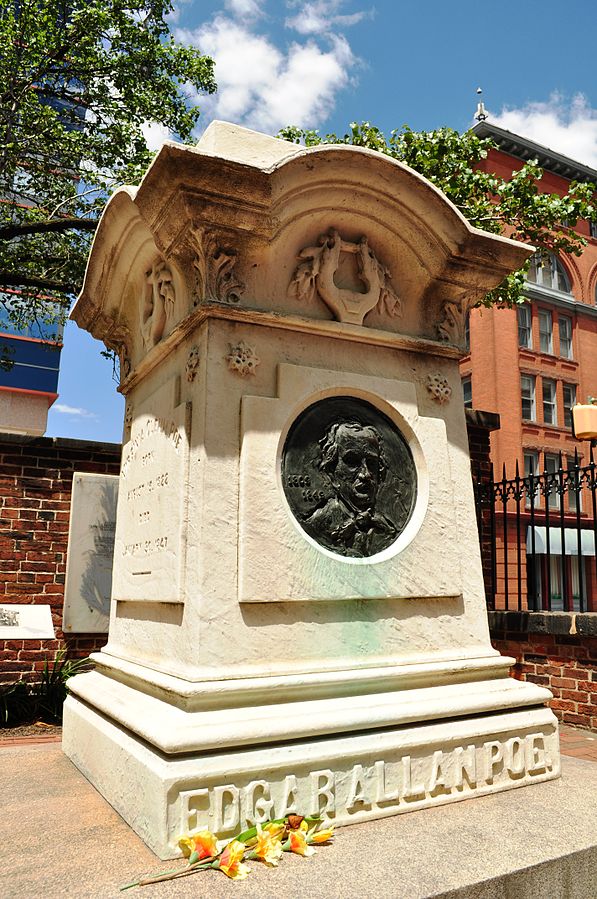

Baltimore has nonetheless cashed in on its Poe connection through his home-turned-museum on North Amity Street, ghost tours and Poe-themed taverns, and a football team named after his poem The Raven (though it was actually written in New York City). As Poe’s fame grew after his death, a Baltimore teacher named Sara Sigourney Rice succeeded in 1875 in reburying the poet beneath a new marble monument, which is now the setting of the Poe Toaster’s visits.2

The tradition of the Poe Toaster dates back at least to 1949, the first year the Baltimore Sun published a report of “an anonymous citizen who creeps in annually to place an empty bottle (of excellent label)” on Poe’s Westminster Hall gravesite.3 He would slip into the cemetery, leave his offering on Poe’s grave, and slip back out. Sometimes, he would leave a note expressing his admiration for Poe or assuring the poet that he had not been forgotten.

He would arrive for his toast between midnight and six o’clock on January 19th, Poe’s birthday, always wearing a large black hat and a white scarf. The original Toaster would always leave the roses in the same configuration, and left the same French label of cognac. After several years of visits, Jeff Jerome, the curator of the Poe House and Museum began waiting inside the church to await the Toaster. Neither Jerome nor anyone else ever uncovered the Toaster’s true identity, but Jerome knew the genuine Toaster from any copycats by “a secret signal” they began to exchange before the figure entered the cemetery.4

Sometimes Jerome waited with university students or friends to see the Toaster, who sometimes “outwitted” them by slipping out unseen.

“We would never attempt to photograph him, or stop him. We had no thought of confronting him,” Jerome said. “People… don’t want to know who he is. This is a nice mystery, and there aren’t a lot of mysteries left.”5

The Toaster’s rationale for the roses and the cognac remains a mystery. Neither feature as prominent symbols in his writing—cognac is never mentioned in Poe’s stories and roses appear only in passing. In the Toaster’s defense, cognac is significantly easier to find in the United States than Amontillado. The three roses are believed to represent Edgar Allan Poe, Maria Clemm (Poe’s mother), and Virginia Poe (his wife), both of whom are buried with Poe in the cemetery at Westminster.

This tradition continued uninterrupted (though hardly unobserved) for decades until, in 1993, a different type of note appeared after the Toaster’s visit. Cryptically, it announced that “the torch will be passed.” In 1999, another note was left to report that the original Toaster had passed away the year before.6 The visitor who slipped into the cemetery that year appeared to be a younger man.

The mantle of the Poe Toaster seemed to have been passed from the original down to one or two sons, who traded the yearly visit—now more of an obligation than ritual of respect—between them. A reporter, Bob McMillan, described how the gravitas and elegance of the original Toaster were not so evident in his replacements:

“The sons didn’t always take the tradition as seriously as their father. Sometimes the Toaster showed up in street clothes. Sometimes notes were left that strayed away from Poe or his work, and a disappointed [Jeff] Jerome withheld them” from the public.7

Two notes from the new Toaster stood out as particularly egregious. In 2001, the Toaster arrived at 2:25 in the morning and knelt at Poe’s grave to deliver the yearly offering. He then “flashed two thumbs up” at the gathered observers before leaving. Between the roses and the cognac, he had left a note referencing Poe’s Masque of the Red Death and The Cask of Amotillado. Right before the Baltimore Ravens faced the New York Giants in the 2001 Super Bowl, the Poe Toaster wrote:

“The New York Giants. Darkness and decay and the big blue [the Giants’ nickname] hold dominion over all. The Baltimore Ravens. A thousand injuries they will suffer. Edgar Allan Poe evermore.”8

The note caused a stir: why would the Toaster turn so sour on Baltimore and especially the Ravens, named after one of Poe’s most enduring images? How could he? (The joke was ultimately on the new Toaster: the Ravens won the match 34 to 7).

Three years later, in 2004, Jerome discovered a note whose “political tone” made him “nervous” about releasing to reporters. Tensions between the US and France had flared over the invasion of Iraq, and the new Toaster wrote that the grave and “sacred memory” of an American poet was “no place for French cognac.” That year’s bottle of Martell was left “with great reluctance.”9 It seemed the Toaster’s agenda had begun from slip from Poe’s works to sports and politics.

Nonetheless, Baltimoreans and fans of Poe continued to stand watch every January 19th, waiting for the Poe Toaster to make his annual visit to the poet’s grave. For one Baltimore resident, the yearly tradition matched the anticipation of Christmas morning: “You know it shows up, but the anticipation and the buildup and how it’s going to happen is ten times more fun.”10

But in 2009, as suddenly as the original Toaster had appeared, his successor failed to make an appearance. In 2010, it was the same. Four years of absences passed. In 2012, after waiting all night in Westminster Hall to no avail, Jeff Jerome officially declared the tradition over. It was an especially rough year for Poe fans: that past February, Jerome had announced that the Poe House and Museum was struggling financially and could close its doors.

In the face of the Toaster’s disappearance, on subsequent nights of January 19th several people began to leave other tokens of appreciation on Poe’s grave. Perhaps they hoped to be recognized as the successor to the original Toaster. By the media, though, they were “referred to somewhat dismissively as ‘Faux Toasters’.”11 Jerome gave them “an A for effort” but would not acknowledge any replacements.12

It seemed the Poe Toaster had indeed croaked “nevermore,” but in 2015, the Maryland Historical Society made an unexpected announcement. Partnering with the Westminster Burying Grounds, Baltimore was searching for a new Toaster. The competition was open to anyone willing to submit a pitch for a three-minute performance “honoring the life and spirit of Edgar Allan Poe.” The committee would consider anything from song to dance to orations, “as long as it’s connected to our dear friend Edgar.”13

The very next year, the Toaster did indeed return, although in a far more visible ceremony than ever before. Festivities were held outside of Westminster Hall in daylight on January 16 to attract a weekend crowd. Fans of Poe listened to a reading of The Cask of Amontillado, toasted with apple cider, and bid on a Poe-themed cake—but the real star of the show was the figure in black that had been absent for half a decade.

The new Toaster—still kept anonymous—entered in the traditional black ensemble and white scarf. In a new twist, he had a violin and performed Camille Saint-Saëns's Danse Macabre as he approached the grave marker. Before the crowd of spectators, he solemnly laid the three roses and over the white stone, toasted a glass of cognac, and left his violin leaning against the grave before retreating back into the cemetery.

Why “resurrect” the Toaster? To Jerome, it seemed like time. The candidate chosen by the Maryland Historical Society created a “solemn, yet touching” tribute that paid homage to the original and added his own flair. And the city needed its mysterious visitor back. As Jerome told a reporter: “This is just so Baltimore.”14

Ever since, the Poe Toaster has made his visit with the same conscientious consistency, respect, and mysterious flair as the original Toaster in 1949. Fans of Poe both local and distant still gather outside Westminster Hall in the freezing January night to catch a glimpse of him or hear the lilting sound of a violin as the newest Toaster approaches the grave of Baltimore’s favorite poet.

Footnotes

- 1

Ayers, Ed. “Edgar Allan Poe’s America - New American History - Medium.” New American History, January 17, 2024. https://medium.com/new-american-history/edgar-allan-poes-america-304e64115fea.

- 2

Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. “Miss S. S. Rice.” Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Baltimore - Poe’s Memorial Grave. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://www.eapoe.org/balt/poesrice.htm.

- 3

Nuckols, Ben and Joseph White. 2010. "Visitor to Poe's Grave Fails to show." Los Angeles Times (1996-), Jan 24, 1.

- 4

Maryland Public Television. “The Poe Toaster.” Knowing Poe: The Poe Library, 2002. https://knowingpoe.thinkport.org/library/news/toaster.asp.

- 5

Chip Brown Washington Post,Staff Writer. 1983. "Evermore: Roses, Cognac at Poe's Grave: Frock-Coated Man Pays Homage at Grave."

- 6

Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. “Poe’s Memorial Grave.” Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Baltimore, 2016. https://www.eapoe.org/balt/poegrave.htm.

- 7

Eschner, Kat. “Who Was the Poe Toaster? We Still Have No Idea.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 19, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/who-was-poe-toaster-we-still-have-no-idea-180961820/.

- 8

"A Fan Takes Poetic License." 2001.Los Angeles Times (1996-), Jan 20, 2001.

- 9

Washington Times. “‘Toaster’ Rejects French Cognac at Poe’s Grave.” The Washington Times, January 19, 2004. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2004/jan/19/20040119-100633-6879r/.

- 10

Washington Times. “‘Toaster’ Rejects French Cognac at Poe’s Grave.” The Washington Times, January 19, 2004. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2004/jan/19/20040119-100633-6879r/.

- 11

Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. “Poe’s Memorial Grave.” Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Baltimore, 2016. https://www.eapoe.org/balt/poegrave.htm.

- 12

Kaltenbach, Chris. 2012. "Poe's 'Toaster' Visits Nevermore: A Tradition is Declared Dead as an Annual Visitor to the Author's Grave Fails to show." Los Angeles Times (1996-), Jan 20, 1.

- 13

Debczak, Michele. “The Search for Baltimore’s Next Poe Toaster.” Mental Floss, October 7, 2015. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/69564/search-baltimores-next-poe-toaster.

- 14

Watson, Jack. “WMAR 2 News Baltimore.” WMAR 2 News Baltimore, January 19, 2023. https://www.wmar2news.com/news/local-news/poe-toaster-tradition-carries-on-at-famed-poets-gravesite.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)