Dunbar: The Evolution of America's First Black Public High School

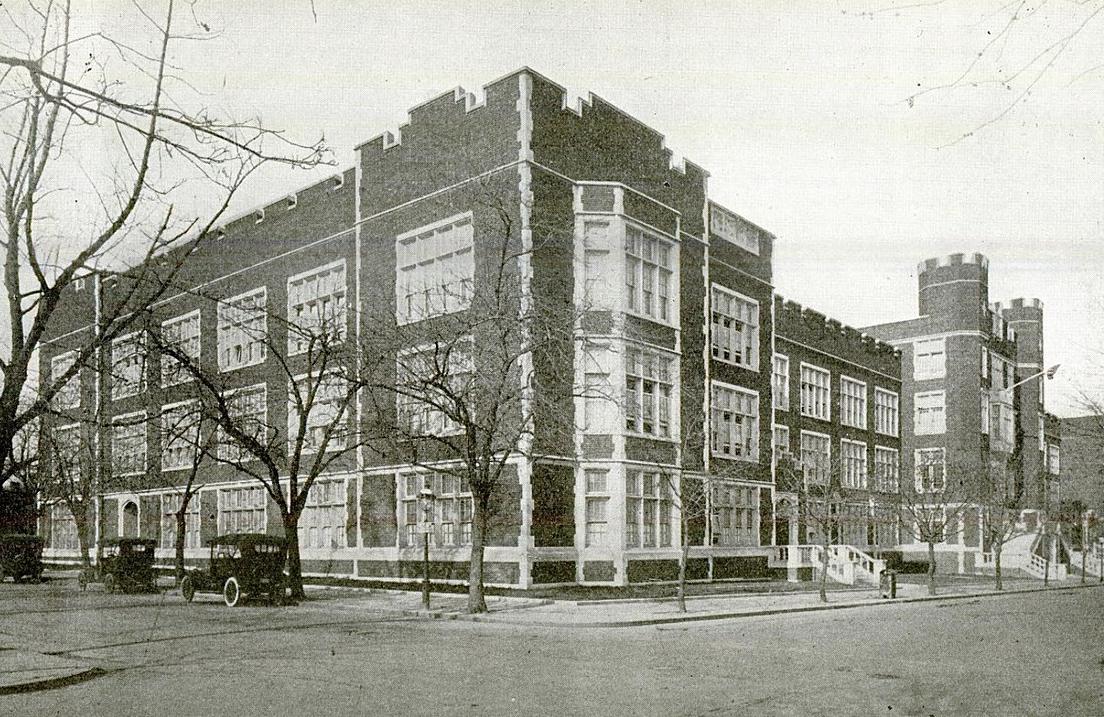

In January 1917, Paul Laurence Dunbar High School celebrated the dedication of its new $550,000 building with a week-long program, showcasing its prestige in the capital city. As the Washington Times reported:

“The Dunbar High School was characterized as the finest high school in this country for the education of colored youth by speakers at last night’s dedication exercises held at the school on First Street between N and O Streets…The school was dedicated to a “greater work than this city has ever known.”’1

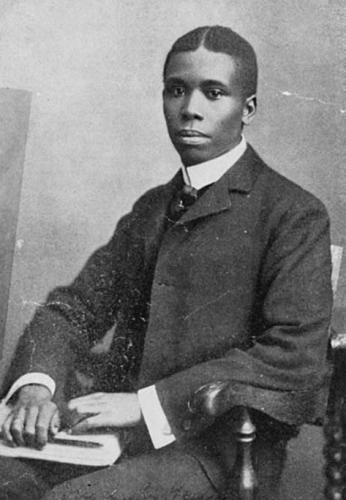

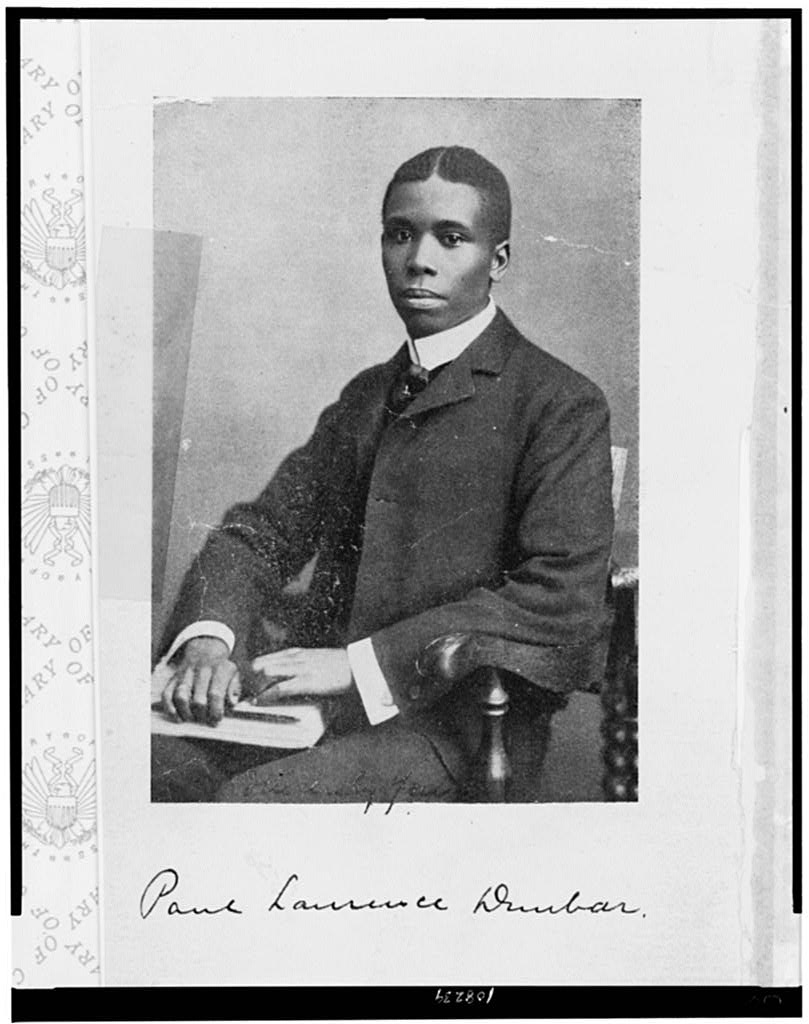

The weather was cold but that didn’t stop a great exhibition of the school’s chorus, basketball and volleyball teams, and performance clubs. A prayer and musical performance opened each ceremony and past principals such as Justice Robert Terrell and Dr. Richard Greener gave addresses to an audience that included former students, members of Congress, the Board of Education, city officials, and the school’s architect, Snowden Ashford. The most memorable attendee was Matilda Dunbar, the mother of the late “Keep a Pluggin Away” poet who was the school’s namesake. Dunbar had passed ten years earlier, yet readings of his poetry were central to the school’s dedication.2

The celebration was decades in the making. Dunbar – America’s first public high school for black students – could trace its roots back to 1870 when some of the District’s most prominent black families pushed to open a school for their children. The school was publicly funded and organized under the supervision of the Board of Trustees of the Colored Schools in Washington.3

Just five years after the Civil War, the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth began holding classes in the basement of 15th St Presbyterian Church. Its purpose: “economize teaching force” and “present to the pupils of the school incentives to higher aim in education.”4

By the fall of 1891, enrollment had skyrocketed, so the school settled into a building on M Street, NW, near the intersection of New York and New Jersey Avenues where it built an impressive faculty.5

Particularly influential was Anna Julia Cooper, who served as principal during the high school’s M Street years and continued to teach at Dunbar after its 1917 christening. While education was recognized as a tool for progress, she steered the school’s curriculum toward the W.E.B. Du Bois philosophy of classical liberal arts education.6 Courses included English, history, sciences, foreign languages, and fine arts. Dunbar was among the first black public schools to have a “Negro History” class.7 Five to seven courses by day equated to five to seven hours of homework for students in the evening. And for those students who needed to accommodate an education and regular employment, the school provided both night and summer classes.8

Cooper and others held to this philosophy even as white school officials like P.M. Hughes widely supported vocational studies for African American students as championed by Booker T. Washington.9 While Washington’s industrial curriculum appeased racial tensions farther South, parents who sent their kids to Dunbar maintained a commitment to classical education, not industrial service. For this, M Street/Dunbar stood apart from its rival, the Armstrong Manual Training School, which opened in 1902 and offered a more vocational curriculum.10

The results were impressive. As historian Rayford Logan wrote of his alma mater, “M Street High School was one of the best high schools in the nation, colored or white, public or private.”11 Indeed, M Street/Dunbar was an anomaly in the Jim Crow era. There wasn’t any place like it, and it outperformed white schools which followed the same classical curriculum.12

Writing in the Journal of Negro History in 1917, Mary Church Terrell described the school’s impact:

“It is very clear that this high school has given a wonderful intellectual impetus to the youth of Washington, many of whom would have been unable to get even a sip at the fountain of knowledge, if they could not have quenched their thirst without money and without price…And here in Washington, if you meet a skillful physician, an excellent teacher, an expert typewriter, or stenographer, a faithful, efficient letter carrier, a distinguished officer in the national guard, or a good citizen on general principles, you are likely to find a graduate of this high school or somebody who has studied there.”13

Dunbar was “the destination” for hundreds of high school age children and its promise of “creating generations of leaders” attracted students from all over the country.14 The expectations were clear. “Everybody who went to that high school was expected to go to college,” recalled alumna Florence Ladd who went on to become a dean at Harvard. And that wasn’t all: “We were taught that we had to be better than white students at the next level when we went to university.”15

Students’ post-graduation accomplishments reflected the investment of their teachers. “Teachers were achievement-motivated…pushing to do the best, but the parents were pushing; everybody was pushing…yet we had a camaraderie among ourselves,” remembered Roscoe Brown, an alum who went on to become a Tuskegee Airman.16

Due to the isolating boundaries of Jim Crow, the black community of Washington became self-dependent. Though college educated, teachers at Dunbar found that racial prejudice inhibited employment outside of black institutions and the federal government. As a result, graduates of the Dunbar School often returned to teach and serve their own communities in medicine, law, religion, and otherwise. Jazz musician Billy Taylor reflected, “Dunbar was a unique place at that time because I was taught by teachers on the faculty who had doctorates.”17

Given its track record and popularity, Dunbar had prolonged overcrowding issues. Since the end of Reconstruction, African Americans had fled the South for the opportunities that urban life could provide such as work, education, and distance from racial terror. Ten years after its 1917 opening, the Washington Tribune reported: “Dunbar is still congested. It was originally built to accommodate 1,200 students. This congestion will be relieved by a staggered-program. Many classes will meet as early as 8:15 in the morning. A double lunch period will be put into effect. One-half of the school will be at recess and the other half in recitations. It may be necessary also to add an hour for certain classes after the closing period.”18 That year, Washington’s black school system broke enrollment records. Dunbar’s newest class entered with over 1500 pupils.19 The overcrowding would get worse in the decades to come.

Insufficient funding and resources were a common hardship for most black educational facilities during Jim Crow. Just as they had been the backbone of the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth decades before, black parents in Washington actively protested the clear inequality of Dunbar compared to its white counterpart, Central High School. In 1948, the Chicago Defender reported that “a survey conducted by a parent’s committee” revealed that “considerable unused space is going idle in so called ‘white’ schools in the District while Negro students are forced to double up.”20 It angered parents that while over enrollment at Dunbar and other black schools required that classes be held after regular school hours, Central High was operating at less than capacity. And yet, Dunbar lacked recreational facilities whereas white schools enjoyed newer stadiums and better swimming pools.21

In the late 1940s, frustrated parents formed the Consolidated Parent Group in hopes of ratcheting up pressure on the city to address the inequalities. Focused initially on Brown Junior High School, the group soon allied parents with civil rights attorneys — among them Dunbar graduate Charles Hamilton Houston — to combat the inadequacies of black schools across Washington. Flyers invited the community to bake sales and church meetings to garner more support for a legal battle against the Board of Education’s neglect of black school conditions.22 After Houston died of a heart attack in 1950, his prodigies Thurgood Marshall, James Nabrit, and George EC Hayes took the legal reins over the school cases. The desegregation campaign eventually arrived to the nation’s highest court in the form of Bolling v. Sharpe, a companion case to Brown v. Board of Education.

Separate schooling had been “an established part of the District’s social fabric” for eight decades before the high court’s 1954 court ruling in Brown outlawed segregation in schools on the basis of race.23 Legal integration in the city did not result in white and black students attending Dunbar or Central together. Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, many whites moved to the suburbs while more southern black migrants flocked into the city. As a result, Dunbar retained its racial makeup – the school remained almost completely black.24 It also ceased being a magnet for students across the city and beyond thanks to the D.C. Board of Education’s new policies, which restricted Dunbar’s population to those students living in the vicinity of the building: “Attendance of pupils residing in school boundaries…shall not be permitted at schools located beyond such boundaries.”25

To a large degree, Dunbar students in the following decades were not the children of parents who had attended Dunbar and gone on to places like Howard University, Miners Teachers College, and Amherst. They were not middle class and “college bound”, programmed for the rigor and discipline of Dunbar’s academic methods. New students were estranged from the school’s heritage on account of their lower-class backgrounds. A well-equipped faculty and classical curriculum could not protect them from the implications of urban poverty.

D.C. Education administrator, Barbara Dodson Walker explained that prior to Brown, Washington’s black community, “had one school that was college preparatory, one school that was vocational and one school that was clerical and when you came out of those schools, you had a skill…when we broke up that system, it tried to make every school a community school.”26 The circuit of black schools in Washington prior to desegregation provided pathways for every kind of student. The boundary policies that followed that era restricted students, with a wide range of academic interests, into one specific school.

After decades as a beacon of black excellence in the face of Jim Crow and destination for the highest achieving students, Dunbar transitioned into a neighborhood school and lost much of the prestige that had been its calling card for decades.27 A well-equipped faculty and classical curriculum could not protect them from the implications of urban poverty. Meanwhile, the city continued to transform around the aging campus that had opened to so much fanfare in 1917.

Following the unrest of the late ‘60s, proposals for a new Dunbar High School building kicked off a debate between Dunbar alumni and a new generation of community leaders. As scholar Amber Wiley has noted, the debate reflected an intracommunity struggle between the sentiments of an older class and the desires of a newer, younger Washington.28Those in favor of demolition – which included the school’s administration and many city officials – argued that a new, more modern campus would serve students better. Meanwhile, preservationists and many graduates, like alumna Marjorie Parker, argued for the preservation of the 1917 building, as a monument of black excellence, which had flourished “in spite of the handicap of a segregated school system.”29 As Washington Post columnist William Raspberry wrote:

“The old Dunbar building is more than fine architecture, although it is assuredly that. It is the embodiment of the proposition that black children, rich and poor, can, if excellently taught, achieve excellently.”30

In 1975, a newly elected D.C. city council approved the old Dunbar’s demolition. It was replaced in 1977 by a new building next door, which touted an open floor plan and brutalist aesthetic. The 1917 campus “succumbed to the wrecking ball” to make room for a football stadium and track.31

The demolition marked a change for the Dunbar community but the spirit of the original school lived on. As alumnus Brigadier General Elmer T. Brooks recalled, long after the demolition, alumni supported pupils of later decades to “increase scholarships and financial aid…and help the school along.”32

As it turned out, the high-rise structure which opened in 1977 failed to be the innovative, nurturing campus planners intended. By 2010, D.C. officials unveiled plans to replace the school yet again. Then Mayor Adrian Fenty hoped the new campus would tie back to Dunbar’s rich history. “The historic building was so much a part of the fabric of Washington that I am proud to say we are now poised to build a facility that honors that past…and I anticipate the new Dunbar will not only encourage our students to reach greater heights, but become a catalyst for the ongoing revitalization of this neighborhood.”33 Dunbar’s current building opened in 2013, and featured an original piano from the 1917 building and a statue of Paul Laurence Dunbar.34

Today, the school’s story continues to be written. Despite its changing face over nearly a century, the essence of the original institution lives on in the school’s mission statement: “to ensure that every student reaches their full potential through rigorous and joyful learning experiences provided in a nurturing environment.”35

Footnotes

- 1

“Praise for Dunbar High School Given,” The Washington Times, January 16, 1917, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1917-01-16/ed-1/seq-14/.

- 2

“Dedication of the Dunbar High School, Washington, D.C., Monday-Friday, January 15-19, 1917 at 8 p.m.,” accessed October 17, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t8039/?sp=10&st=text.

- 3

Donald Roe, “The Dual School System in the District of Columbia, 1862-1954: Origins, Problems, Protests,” Historical Society of Washington 16, no. 2 (2004): 26–43, https://www.jstor.org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/stable/40073395.

- 4

Mary Church Terrell, “History of the High School for Negroes in Washington,” The Journal of Negro History 2, no. 3 (July 1917): 252–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/2713767.

- 5

Henry S. Robinson, “The M Street High School, 1891-1916,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 51 (1984): 119–43, https://www.jstor.org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/stable/40067848.

- 6

Kenneth Alphonso Mitchell, “The Story of Dunbar High School: How Students from the First Public High School for Black Students in the United States Influenced America” (M.A.L.S., United States -- District of Columbia, Georgetown University, 2012), https://www.proquest.com/docview/1010995644/abstract/BF3656A8D28D427CPQ/4.

- 7

“Negro History Week,” The Hilltop, February 18, 1926.

- 8

“Open Summer Schools for D.C. Colored Pupils,” The Washington Times, July 7, 1920, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1920-07-07/ed-1/seq-5/.

- 9

Mitchell, “The Story of Dunbar High School: How Students from the First Public High School for Black Students in the United States Influenced America”.

- 10

Robinson, “The M Street High School, 1891-1916”.

- 11

Rayford W. Logan, “Growing Up in Washington: A Lucky Generation,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 50 (1980): 500–507, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40067833.

- 12

Mitchell, “The Story of Dunbar High School: How Students from the First Public High School for Black Students in the United States Influenced America”.

- 13

Terrell, “History of the High School for Negroes in Washington”.

- 14

Paul Brock, Jay Harris describes his mother’s childhood in Washington, D.C., October 7, 2005, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/428452.

- 15

Larry Crowe, Florence Ladd describes her experience at Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., April 11, 2003, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/86536;q=dunbar%20high%20school%20%28washington%20dc%29%20.

- 16

Julieanna Richardson, Roscoe C. Brown describes the competitive academic environment at Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., September 16, 2003, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/178777.

- 17

Shawn Wilson, Billy Taylor describes his educational experiences in Washington, D.C., August 29, 2005, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/290531;q=billy%20taylor%20%22dunbar%20high%20school%22.

- 18

“Registration in Schools Breaks Previous Records,” The Washington Tribune, September 23, 1927, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062236/1927-09-23/ed-1/seq-1/.

- 19

Ibid.

- 20

“Overcrowding Lowers Rating of D.C. Schools,” Chicago Defender, May 29, 1948, https://www.proquest.com/docview/492845806/5D855B7094884AE2PQ/1?accountid=11490&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers.

- 21

Amber N. Wiley, “The Dunbar High School Dilemma: Architecture, Power, and African American Cultural Heritage,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 20, no. 1 (2013): 95–128, https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.1.0095.

- 22

“Consolidated Parent Group Flyers,” accessed October 31, 2024, https://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/4-five/detail/cpg-flyers.html#flyer4.

- 23

“High Court Ponders Big Decision,” The Evening Star, December 14, 1952, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1952-12-14/ed-1/seq-27/.

- 24

Wiley, “The Dunbar High School Dilemma: Architecture, Power, and African American Cultural Heritage”.

- 25

Amber N. Wiley, “The Dunbar High School Dilemma: Architecture, Power, and African American Cultural Heritage,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 20, no. 1 (2013): 95–128, https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.1.0095. Wiley cites Board of Education, "Bolling v Sharpe," n.d., Series 2: Speeches, Statements, and Remarks, 1961-1967, Box 1, Folder 33, Walter Tobriner Papers, Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University.

- 26

Sandra Ford-Johnson, Barbara Dodson Walker talks about the benefits of racially segregated schools and separate vocational schools in Washington D.C., March 4, 2004, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/201793.

- 27

Wiley, “The Dunbar High School Dilemma: Architecture, Power, and African American Cultural Heritage”.

- 28

Ibid.

- 29

LaBarbara Bowman, “Council Votes to Raze Dunbar High School,” The Washington Post (1974-), April 15, 1975, sec. METRO Local News/Obituaries/Classified, https://www.proquest.com/docview/146400949/abstract/838A448006442CBPQ/1.

- 30

Wiley, ‘The Dunbar High School Dilemma: Architecture, Power, and African American Cultural Heritage”.

- 31

Ibid.

- 32

Robert Hayden, Brig. Gen. Elmer T. Brooks describes Paul Laurence Dunbar High School’s facility in Washington, D.C., November 10, 2006, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/392905;q=new%20dunbar%20high%20school%20dc.

- 33

“Dunbar Design Team Named,” Washington Informer, December 16, 2010, sec. EDUCATION: Briefs, https://www.proquest.com/docview/820633755/abstract/E4EFF875E901412EPQ/3.

- 34

Emma Brown, “D.C. Leaders to Celebrate New Dunbar High School Facility,” Washington Post, August 18, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/dc-leaders-to-celebrate-new-dunbar-high-school-facility/2013/08/18/19f8374c-0832-11e3-8974-f97ab3b3c677_story.html.

- 35

“Mission and Vision,” accessed September 18, 2024, https://www.dunbarhsdc.org/about_us/mission_and_vision.

![This integrated classroom at Anacostia High School is the culmination of a seven year struggle against DC's segregated school system. [Source: LOC] Integrated classroom at Anacostia High School](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/AHS%20Class_0.jpg?itok=GNxSJFox)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)