The Anti-Flirt Club: The Movement to End Unwanted Attention in the 1920s

For many women living in cities, cat-calls from random men are a far too common occurrence. Sadly, this street harassment is nothing new and since at least the late 1800s, it has been a social issue targeted by reformers.

One of the early efforts to curb unwanted advances came from Virginia State Senator James G. McCune, who proposed a bill in December of 1897 that would “make it a misdemeanor… for any man or youth to loiter about any female school or seminary.”1

The idea was not well received by some members of the public, including an anonymous poet who penned a ballad in protest of the proposed legislation. It began:

“I will sing you a song, of words without tune.

About flirting, dear boys, by its author, McCune;

The bill he has offered should have little weight;

He’s over the age for a flirt loving state.

The girls will not thank him, of this I am sure;

The boys will condemn him and think him demure…”2

The bill, along with similar anti-flirtation legislation that was being proposed across the country, failed to pass. However, the fight against “flirtation” was just getting started.

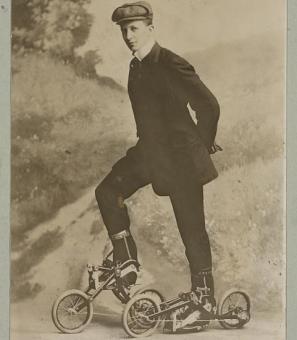

In the early 1910s, the advent of the automobile meant more Americans were on the move. At the same time, World War I brought many workers to Washington and other cities. It became common for male motorists to offer rides to female pedestrians as part of their civic wartime duty. While this practice was sometimes harmless, and maybe even helpful, it quickly became tainted by aggressive advances from male drivers. Many women quickly grew tired of this new kind of harassment and felt, as The Washington Post reported later, that “too many motorists [were] taking advantage of the precedent established during the war by offering to take young lady pedestrians in their cars.”3

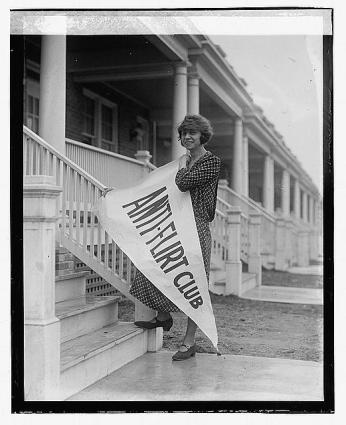

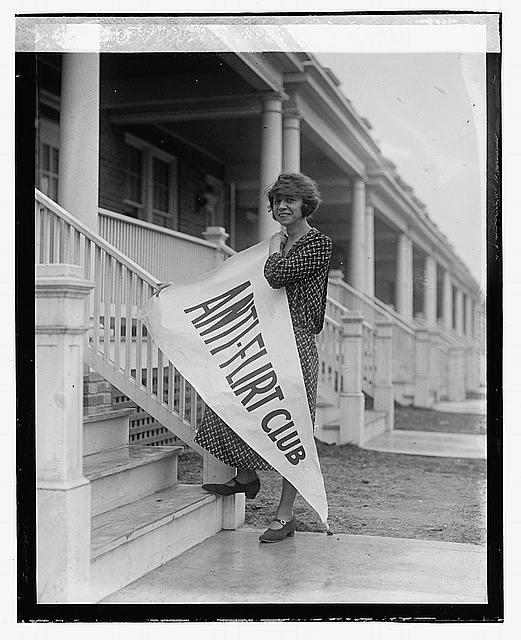

This was exactly the problem that Washington, D.C.’s Anti-Flirt Club aimed to solve. Founded in 1923 by ten D.C. women and led by Alice Reighly, the group was “a passive offensive against the curbstone loafer and flirtatious motorist”4 born out of the women’s desire to evade being “embarrassed by men in automobiles and streetcorners,” a reality that remains all too familiar.5 The club decided to start targeting drivers because, in the words of club secretary Helen Brown, “there are many other types of flirts, but the motorists are the worst.”6

News of the group’s first meeting on February 27, 1923, made the front page of the Evening Star, under a headline reading “‘Anti-Flirt’ Club to Launch Drive Against Auto Oglers.”7

The goals of the club were quite straightforward: they wanted to put a stop to the flirting and promiscuity that had become so prominent. This agenda was laid out in a list of ten rules, which were shared in the Evening Star and Washington Post:

- Don’t flirt: those who flirt in haste oft repent in leisure.

- Don’t accept rides from flirting motorists—they don’t invite you in to save you a walk.

- Don’t use your eyes for ogling—they were made for worthier purposes.

- Don’t go out with men you don’t know—they may be married, and you may be in for a hair-pulling match.

- Don’t wink—a flutter of one eye may cause a tear in the other.

- Don’t smile at flirtatious strangers—save them for people you know.

- Don’t annex all the men you can get—by flirting with many, you may lose out on the one.

- Don’t fall for the slick, dandified cake eater—the unpolished gold of a real man is worth more than the gloss of a lounge lizard.

- Don’t let elderly men with an eye to a flirtation pat you on the shoulder and take a fatherly interest in you. Those are usually the kind who want to forget they are fathers.

- Don’t ignore the man you are sure of while you flirt with another. When you return to the first one you may find him gone.8

As humorous as some of these missives may seem today, the rules were intended to be sound and serious advice for women feeling overwhelmed by various types of so-called flirts. Notably, the list puts the responsibility of deterring catcalls on the woman – the ones being catcalled – rather than the men doing the harassing.

The Anti-Flirt Club shared their list of “don’ts” with other women’s organizations, who they hoped would also adopt them. Meanwhile, they began to put their words into action with the first (and last) Anti-Flirt Week, which began March 4, 1923, not even a week after the club was founded. The organization produced buttons and flyers and encouraged other groups to recognize this newly declared week.

The effort made headlines across the country, though the reporting was, unsurprisingly, a little sexist. As one newspaper from Indiana noted, while winking was explicitly banned for club members, club founder Reighly “wields a wicked eyelash.”9 The media coverage caught the attention of Manuel Herrick, a Representative from Oklahoma known as the “Okie Jesus Congressman” due to his mother’s belief that he was Jesus.10

In a letter to the club, Herrick said he saw a lot of potential in their mission and suggested that “any young man who wishes to call upon a member of the club should give a complete history of himself, which shall be verified by the club before he is granted the privilege of calling.”11 He also claimed to be particularly fond of rules four, seven, and eight but cautioned: “[You] will fall far short of your opportunity for doing something really worthwhile for the female sex if you do not make your club the nucleus of a nation-wide order of anti-flirts.”12

Herrick was, to put it blunty, an odd “ally.” In 1921, he had obtained the contact information for 49 women in a District beauty pageant. He sent letters to each of them -- and even visited some at their homes -- with an invitation to participate in another contest. The winner would receive the hand in marriage of “one of the 15 men who is now living on the earth who can look God in the eye and say, 'Against my body and against my soul there rests no moral stain, for I have kept my soul and my body free from all moral stain in order that I may look my virgin bride in the eye without guilt and shame in my heart.’"13 Herrick, of course, was referring to himself.

When news of his actions began to get out, he claimed the whole thing was a stunt to demonstrate how pageants preyed on young women -- a follow up to a recent House bill he had introduced banning such contests. "While this may be a little bit underhanded or seem so to some people, it is for the protection of these girls, it is for their own good, and for a worthy cause," he told the Washington Times. 14 The ban failed to pass, but apparently Herrick found a new way to “protect” the young women of America with his endorsement of the Anti-Flirt Club.

As Herrick was offering his unsolicited support in Washington, similar anti-flirting clubs began to pop-up in other cities, such as New York and Chicago, around the same time. In New York, the “Anti-Flirt Association” was composed of five men who wanted “to educate public opinion to the point where a woman will consider it her duty to prosecute the masher who attempts to force his attentions upon her.”15 Although responsibility would still fall on the woman to take action against the “masher,” at least action would being taken. The New York Anti-Flirt Association even intended to have its own council who would aid in prosecuting the overzealous flirters.16

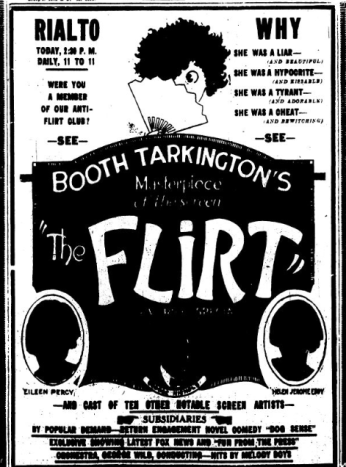

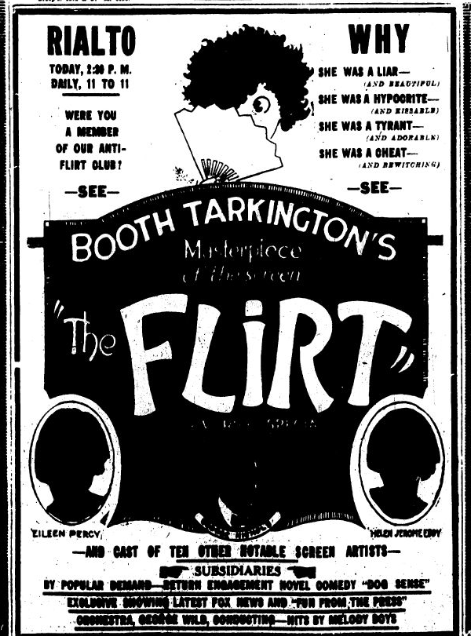

Interestingly, the rhetoric from the Anti-Flirt Club also found its way into the advertisement campaign for a movie called “The Flirt.” The movie was based on a 1913 Booth Tarkington novel of the same name and shared the “story of a girl who had to have her own way.”17 Ads for “The Flirt” appeared in newspapers, with a nod to the Anti-Flirt Club and their rules. One ad in the Evening Star read "A smile in time saves a formal introduction. . . . When the wife's away even nice men play."18 Another teased “Were you a member of our Anti-Flirt club?” 19

The ads were apparently not a coincidence. In 2021, Washington Post columnist John Kelly did some digging and discovered that Anti-Flirt Club founder Alice Reighly and another club member worked for the Interstate Film Corp, which may have been involved with the promotion for the movie. So was the Anti-Flirt Club a publicity stunt to generate interest in the film?20

If so, it may explain the relatively lackluster approach to combating street harassment that the Anti-Flirt Club in D.C. seemed to take. While mashers in New York and Chicago were being arrested for their actions, D.C.'s Anti-Flirt Club was placing the brunt of preventing street harassment on the women being harassed. For many, this might raise some questions about the true purpose of the Anti-Flirt Club in D.C.

The 1920s were a time of great progress for white women – the 19th Amendment was passed, new employment opportunities opened up, and the strict codes of behavior that had existed pre-WWI were being challenged. Women began wearing shorter skirts, they drank and smoked outside the home in gathering places like speakeasies, and sexual freedom became slightly more acceptable.21 With all that in mind, it might seem like an organization that encouraged women to act more modestly goes against the progress being made socially.

Whether or not the Anti-Flirt Club was born out of a true desire to stop street harassment, an effort to encourage women to be demure despite social progress being made, or to promote a film, there was a clear need for the club, as evidenced by similar organizations that popped up across the country. However, the movement was far from revolutionary, and by the end of the 1930s, the anti-flirt campaigns around the country died out.22 Unfortunately, the mashers, lounge lizards, and flirtatious motorists are still going strong. Nevertheless, it is interesting to consider a world where street harassment was taken more seriously.

Footnotes

- 1

“The Anti-Flirtation Bill,” The Daily Times (Raleigh, North Carolina), January 29, 1898, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn95072296/1898-01-29/ed-1/seq-4/.

- 2

“The Anti-Flirtation Bill,” Daily Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), January 24, 1898, https://www.virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DS18980124.

- 3

“10 GIRLS START WAR’S ON AUTO INVITATION,” The Washington Post (Washington D.C), February 28, 1923.

- 4

“‘Anti-Flirt’ Club to Launch Drive Against Auto Oglers,” Evening Star (Washington D.C), February 27, 1923.

- 5

Helen H. Fetter, “Girls and Their Affairs,” Evening Star (Washington D.C), March 4, 1923.

- 6

The Washington Post, “10 GIRLS START WAR’S ON AUTO INVITATION.”

- 7

Evening Star, “‘Anti-Flirt’ Club to Launch Drive Against Auto Oglers.”

- 8

Evening Star, “‘Anti-Flirt’ Club to Launch Drive Against Auto Oglers.”

- 9

John Kelly, “In 1923, Washington Women formed the Anti-Flirt Club,” The Washington Post, April 20, 2021.

- 10

Carolyn G. Hanneman, “HERRICK, MANUEL (1876–1952),” in The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=HE018.

- 11

"This Here Anti-Flirt Move --- Well, It Gets Manuel's O.K.," Evening Star, March 2, 1923.

- 12

"This Here Anti-Flirt Move --- Well, It Gets Manuel's O.K.," Evening Star, March 2, 1923.

- 13

John Kelly, "This Congressman Wanted to Ban Beauty Pageants. So Why Did He Have His Own Contest?" The Washington Post, April 20, 2021.

- 14

John Kelly, "This Congressman Wanted to Ban Beauty Pageants. So Why Did He Have His Own Contest?" The Washington Post, April 20, 2021.

- 15

“Article 1 -- No Title,” The New York Times, November 21, 1922, https://www.nytimes.com/1922/11/21/archives/article-1-no-title.html?searchResultPosition=4.

- 16

The New York Times, “Article 1 -- No Title.”

- 17

“The Flirt (1922),” BFI, n.d., https://web.archive.org/web/20191006132936/https:/www.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b6aa4f9ae.

- 18

“Amusements,” Evening Star (Washington D.C), March 6, 1923.

- 19

“The Flirt Ad,” Evening Star (Washington D.C), March 11, 1923.

- 20

Kelly, “Anti-Flirt Club in 1923: Rules to Dodge Mashers.”

- 21

“Women in the 1920s,” BBC, n.d., https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zdvfydm/revision/1

- 22

Alexis Coe, “Stop That Skirt-Chaser! The Movement to Outlaw Flirting in the 1920s,” The Atlantic Web Edition, February 12, 2013.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)