During the Civil War, Roosevelt Island Was Home to Black Troops and a Freedman’s Camp

While it’s known today for its forested hiking trails and outdoor memorial to America’s 26th president, Theodore Roosevelt Island played a prominent role in Washington, DC’s Civil War history. In 1863, the island became home to Camp Greene, training grounds of the 1st United States Colored Troops (USCT), a Black infantry regiment recruited in the District.

Along with hosting DC’s first black Union soldiers, Roosevelt Island—then known as Analostan Island or Mason’s Island—also provided refuge for hundreds of formerly enslaved persons fleeing north. Through both these capacities, the island served as a powerful local reminder of black Americans’ fight for freedom on both the Southern battlefields and in DC, where slavery had only been abolished by an act of Congress in 1862 and deep racial tensions remained.

Prior to the outbreak of war, Roosevelt Island had a long history of human habitation. Native Americans used it as a hunting camp for thousands of years and John Smith recorded the nearby settlements of Namoraughquend and Nacotchtanck in 1607 and 1608.1 In 1717, the island fell under the ownership of the Mason family of Virginia, giving the island (which had also been referred to as “My Lord’s Island” and “Barbadoes” by colonists) yet another name.2

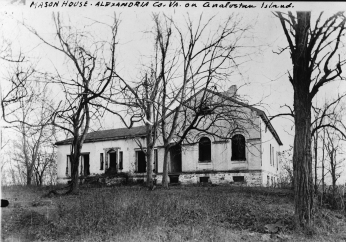

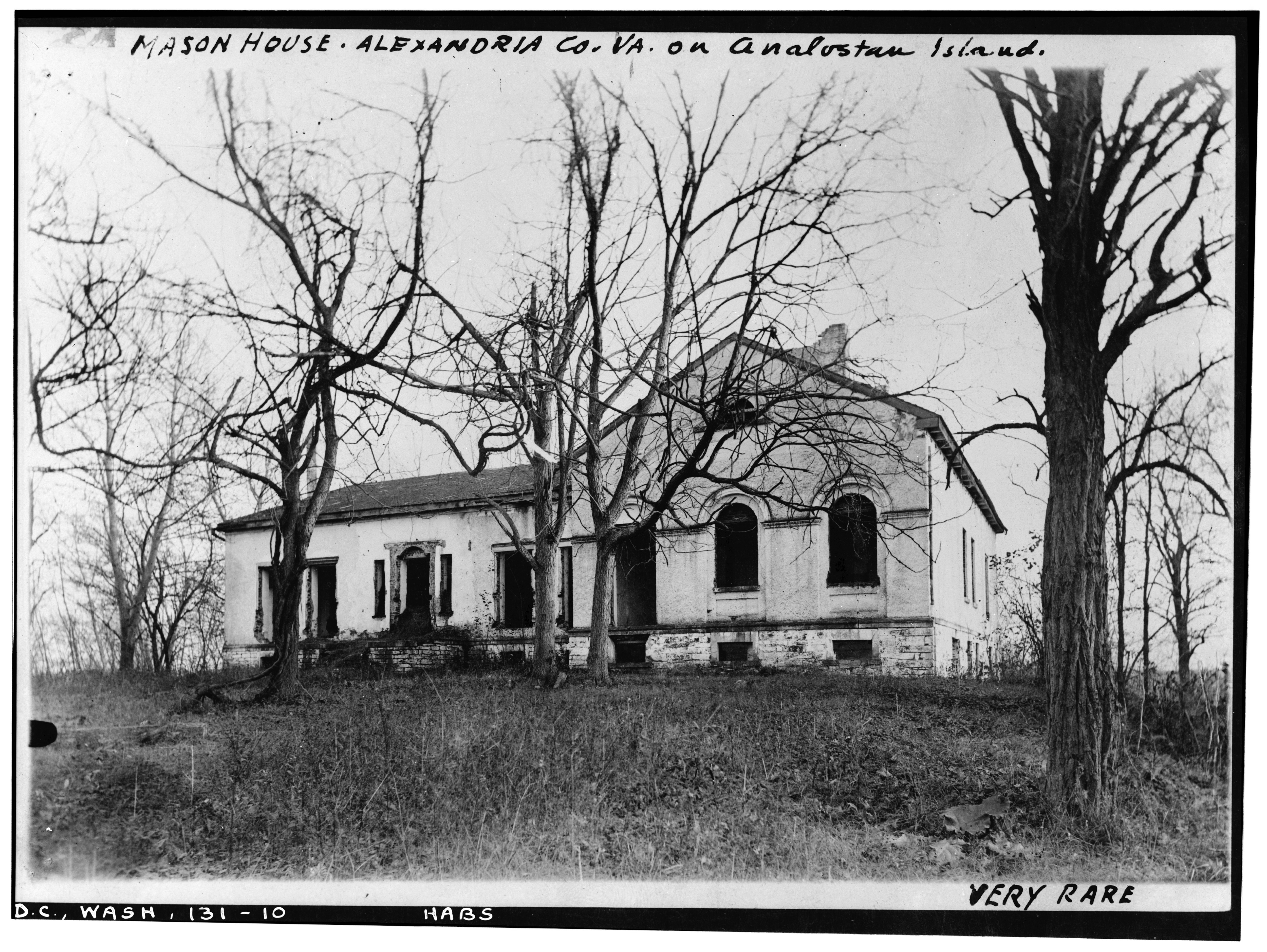

The Masons operated a ferry service to and from nearby Georgetown and in 1802 John Mason, the fourth son of Founding Father George Mason IV, completed a Classical Revival-style mansion on the island with the use of enslaved labor. The Masons ran a plantation, planted extensive gardens, and hosted extravagant parties before selling the island in 1833.3

As the Civil War kicked off, Mason’s Island found itself in a sticky situation, being at the literal crossroads of the North and South. Days after the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861, one New Orleans newspaper opined that secessionist forces could “easily get on that island and throw up batteries” to assault Georgetown and the city.4 Its strategic significance being obvious, the island and surrounding parts of Arlington were quickly occupied by Union troops.

From the start of the conflict, abolitionists including Frederick Douglass called on the U.S. government to overturn a 1792 law that had effectively barred blacks from enlisting in the military (although many still served during the War of 1812).5 In July 1862, with Union casualties mounting and white volunteers dwindling, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act, freeing slaves owned by Confederates and allowing for limited black military service.6

It wasn’t until President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, that blacks were formally cleared for combat duty.7 Several months later in May 1863, the War Department issued General Order 143, creating the Bureau of United States Colored Troops to oversee recruitment and training.8

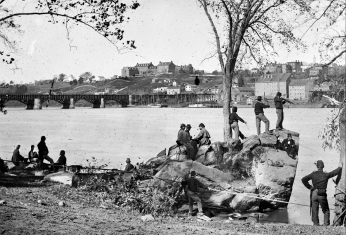

The 1st USCT was officially organized in DC beginning on May 19, 1863.9 A camp constructed on the north end of Mason’s Island that was named after the Chief Quartermaster for the Department of Washington, Lieutenant Colonel Elias M. Greene, would garrison the regiment.10 The Daily National Republican reported that recruits took a ferry across the Potomac that departed from the foot of High Street (today’s Wisconsin Avenue) on the Georgetown waterfront.11 Over 1,000 men had arrived by June 4, according to the papers.12

While blacks could now enlist, the all-black regiments were still commanded by white officers such as Colonel John H. Holman, a Missourian who was put in charge of the 1st USCT.13 Black enlisted men also initially received $3 less per month than their white counterparts (with an additional $3 withheld to pay for uniforms), despite facing the added dangers of re-enslavement or possible execution by Confederates.14

Men of the 1st USCT encountered a host of hostilities in DC, a city with strong ties to Southern culture and slavery. In early June 1863, Corporal John Ross, a black soldier, ventured into the city from Mason’s Island on recruiting duty for the regiment.15 Per one newspaper account, a group of boys began throwing stones at Ross as he passed Northern Liberty Market, near today’s Mount Vernon Square, and the situation worsened as one white onlooker threatened to knock the soldier down.16

“The corporal turned aside up an alley and appealed to policeman No. 84, John F. Parker to protect him,” the New-York Daily Tribune reported.17 “The policeman instead of doing his duty pursued the negro soldier himself and struck him with his ‘billy,’ knocked him down and tore off his chevrons ‘corporal straps.’ The soldier, to defend himself, undertook to draw his pistol, but the crowd were too strong for him.”

Ross was stripped of his enlistment papers by the mob and subsequently taken to a courthouse by Parker, who “entered a complaint against him for disturbance of the peace.”18 A white colonel who witnessed the whole affair fortunately came to Ross’s defense and threatened the judge that he would “deliver [Ross] from his hands if it took his whole regiment to do it.”19 The corporal was eventually sent back to Camp Greene.

The following month Walt Whitman, at the time a local hospital volunteer, decided to pay the 1st USCT a visit. He took an ambulance up Pennsylvania Avenue through Georgetown and crossed the Potomac via the Aqueduct Bridge, which also transported boats for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to Virginia, before arriving at the regiment’s camp.20

“The tents look clean and good; indeed, altogether, in locality especially, the pleasantest camp I have yet seen,” reflected Whitman, who wrote under the shade of trees lining the old Mason House.21 “The spot is umbrageous, high and dry, with distant sounds of the city, and the puffing steamers of the Potomac, up to Georgetown and back again. Birds are singing in the trees, the warmth is endurable here in this moist shade, with the fragrance and freshness.”

The poet witnessed the regiment receive its pay and noted the fine appearance of the troops, writing that “no one can see them, even under these circumstances—their military career in its novitiate—without feeling well pleased with them.”22 That sentiment was echoed by General Silas Casey, who pronounced the 1st USCT “equal to white troops no longer drilled than these men” upon reviewing the regiment on the island.23

At the end of July the 1st USCT departed Mason’s Island for war and served at Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Yorktown, Virginia until April 1864.24 That June the regiment took part in the Union assaults on Petersburg while attached to Major General William F. Smith’s XVIII Corps of the Army of the James. The campaign ultimately featured the war’s largest concentrations of black troops and bitter fighting that foreshadowed the industrialized carnage of World War I.25

At around 7pm on June 15, under the cover of artillery fire, the 1st USCT charged across a field towards a section of earthworks defended by Confederates under Brigadier General Henry Wise, a former governor of Virginia.26

“Away went Uncle Sam's sable sons across an old field nearly three-quarters of a mile wide, in the face of rebel grape and canister and the unbroken clatter of thousands of muskets,” according to regimental chaplain Henry Turner, the unit’s only black officer, who witnessed the fighting.27 “Nothing less than the pen of horror could begin to describe the terrific roar and dying yells of that awful yet masterly charge and daring feat. The rebel balls would tear up the ground at times, and create such a heavy dust in front of our charging army, that they could scarcely see the forts for which they were making.”

Both sides reportedly began crying out “Fort Pillow!,” a reference to a battle from that spring in which Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederates massacred surrendering black troops in Tennessee.28

“But onward they went, waxing stronger and mightier every time Fort Pillow was mentioned,” wrote Turner, whose regiment successfully took the position and leaped into the trenches.29 “The next place we saw the rebels, was going out the rear of the forts with their coat-tails sticking straight out behind. Some few held up their hands and pleaded for mercy, but our boys thought that over Jordan would be the best place for them, and sent them there, with a very few exceptions.”

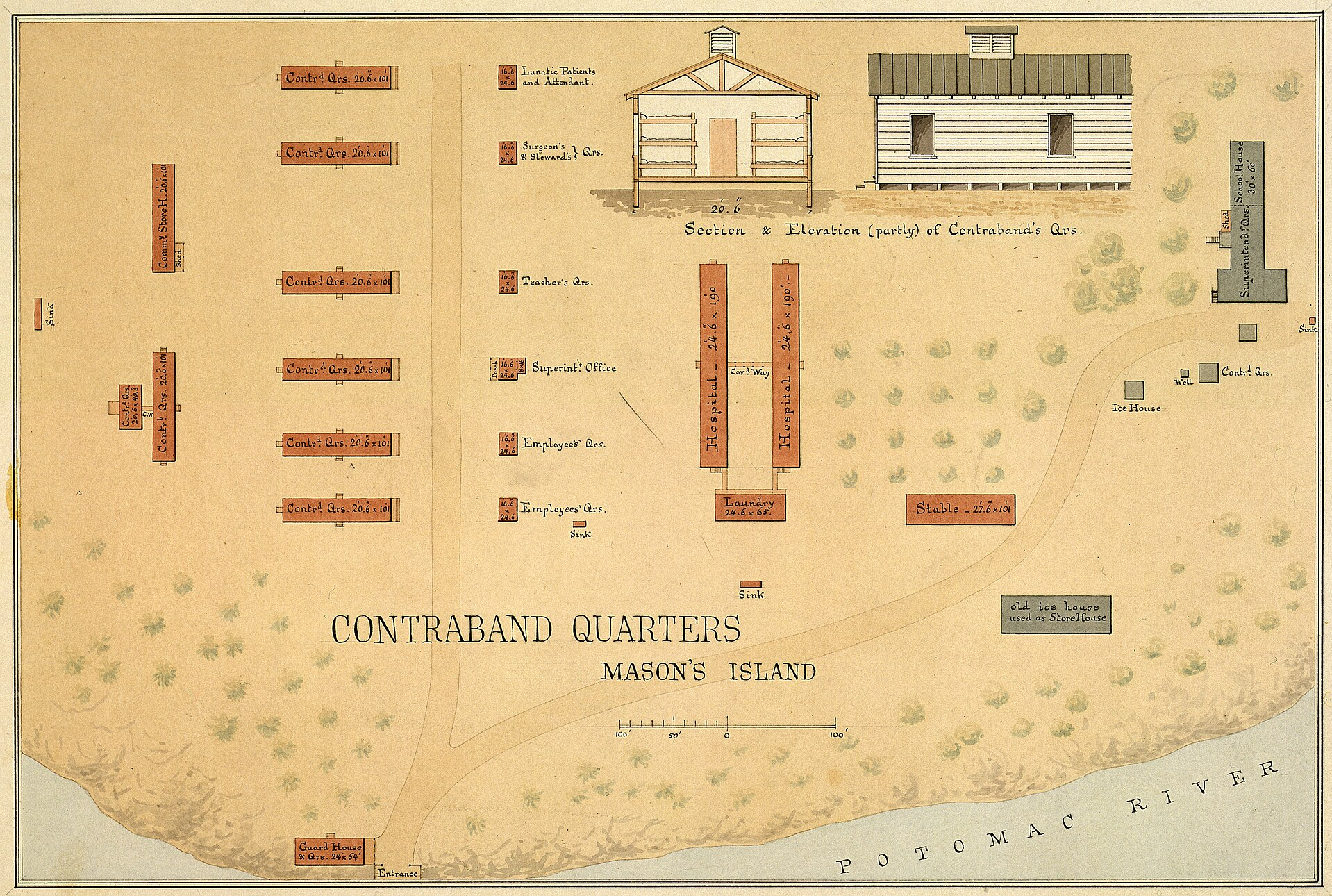

While the 1st USCT fought in the Petersburg campaign, Camp Greene was in the process of being converted to house newly freed and escaped enslaved people seeking jobs in the federal capital.30 Since the regiment departed the camp had been expanded to include wooden barracks, hospitals, stables, and even an icehouse.31 Even so, the island struggled to handle the influx of over a thousand men, women, and children.

Conditions were somewhat improved thanks to donations from local Quakers and families received fresh milk daily courtesy of cows confiscated from rebel farmers.32 Church services were held in the Mason House’s former dancing saloon.33 The island must have made for an eclectic scene, with its mixture of military and plantation buildings, livestock and gardens, all framed by a “dark border of woods along the shore.”34

By late 1865 the camp had shut down and remaining refugees were relocated to the Freedman’s Village at Arlington House.35 Following the closure the government returned the island to its prewar owner, William A. Bradley.36 Few traces remain today of Camp Greene on the island, aside from foundations of the stables and “some large stones that could have been used for building foundations at the camp,” according to the National Park Service.37

As for the 1st USCT, the regiment participated in the capture of Wilmington, North Carolina, on February 22, 1865, before taking up occupation duty and eventually getting mustered out on September 29.38 By war’s end, some 3,500 black Washingtonians had enlisted in the Union Army, with the 1st USCT losing 185 men.39 You can still find a historical marker honoring the regiment on Roosevelt Island today, situated at the same corner of the island where the men first pitched their tents and took up arms for the Union over 160 years ago.

Footnotes

- 1

“A History of Native American Life on Theodore Roosevelt Island,” NPS.gov.

- 2

“Mason House,” NPS.gov.

- 3

“Mason House,” NPS.gov.

- 4

“Washington City,”New Orleans Daily Crescent, April 27, 1861.

- 5

“Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War,” National Archives.

- 6

James A. Percoco, “The United States Colored Troops,” American Battlefield Trust, November 2, 2017.

- 7

James A. Percoco, “The United States Colored Troops,” American Battlefield Trust, November 2, 2017.

- 8

“United States Colored Troops History,” African American Civil War Memorial Museum.

- 9

“United States Colored Troops 1st Regiment Infantry,” NPS.gov.

- 10

“Camp Greene,” NPS.gov.

- 11

“Local News,”Daily National Republican (Washington, DC), June 22, 1863.

- 12

“From Washington,”Chicago Daily Tribune, June 4, 1863.

- 13

“Camp Greene,” NPS.gov.

- 14

United States Colored Troops History,” African American Civil War Memorial Museum.

- 15

“Disgraceful Assault,”New-York Daily Tribune, 11 June, 1863.

- 16

“Disgraceful Assault,”New-York Daily Tribune, 11 June, 1863.

- 17

“Disgraceful Assault,”New-York Daily Tribune, 11 June, 1863.

- 18

“Disgraceful Assault,”New-York Daily Tribune, 11 June, 1863.

- 19

“Disgraceful Assault,”New-York Daily Tribune, 11 June, 1863.

- 20

Walt Whitman, “Some War Memoranda-Jotted down at the Time,”The North American Review, 144, no. 362 (January, 1887): 55-60.

- 21

Whitman, “Some War Memoranda-Jotted down at the Time,” 58.

- 22

Whitman, “Some War Memoranda-Jotted down at the Time,” 60.

- 23

“Review of Colored Troops,”New-York Daily Tribune, July 23, 1863.

- 24

“United States Colored Troops 1st Regiment Infantry,” NPS.gov.

- 25

“African-Americans at the Siege,” NPS.gov.

- 26

“United States Colored Troops in Opening Assaults,” NPS.gov.

- 27

“United States Colored Troops in Opening Assaults,” NPS.gov.

- 28

“United States Colored Troops in Opening Assaults,” NPS.gov.

- 29

“United States Colored Troops in Opening Assaults,” NPS.gov.

- 30

“Freedman's Camp,” NPS.gov.

- 31

“Freedman's Camp,” NPS.gov.

- 32

“A Freedmen’s Village,”The Liberator (Boston, MA), September 16, 1864.

- 33

“A Freedmen’s Village,”The Liberator (Boston, MA), September 16, 1864.

- 34

A Freedmen’s Village,”The Liberator (Boston, MA), September 16, 1864.

- 35

“Freedman's Camp,” NPS.gov.

- 36

“Freedman's Camp,” NPS.gov.

- 37

“Freedman's Camp,” NPS.gov.

- 38

“United States Colored Troops 1st Regiment Infantry,” NPS.gov.

- 39

“United States Colored Troops 1st Regiment Infantry,” NPS.gov.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)