The Wawaset Disaster of 1873

Few remember it today, but in 1873 “the Waswaset horror” broke the hearts of many in D.C. and the surrounding area.

On August 8, 1873, the Wawaset was heading towards Cone River from Washington. Around 11:30 a.m., near Chatterson’s Landing, the fireman of the steamer raised the alarm that a fire had broken out on board. The boat was very dry, “almost like timber,” and it spread quickly on the oiled machinery of the steamer. Captain Woods immediately steered the boat towards shore. He stayed in the pilot’s house in order to keep the steering ropes from catching on fire; if those were lost, there would be no way to direct the steamer. If the steamer could make it to shore before the fire became too much for those on board, any loss of life could be avoided.

Sadly, it didn’t happen that way.

Because the fire broke out in the middle of the steamer, communication between the forward and rear parts of the boat entirely ceased and, unfortunately for those at the front, the lifeboat was at the back of the boat. Not that the lifeboat did much good anyway. It broke under the weight of frightened passengers and sank upon entering the water, drowning everyone in it. The other safety boats aboard the Wawaset were unreachable, as they were being consumed by flames.

The life preservers, too, were being steadily engulfed in flames while the passengers of the Wawaset contemplated death by water. Only two of the people aboard, a Mr. Emerson and his daughter, were able to benefit from the life preservers. Mr. Emerson was later so grateful that he and his child had been spared that he took the preserver back with him to his home in Alexandria and vowed to keep it as long as he lived.

As the boat neared the shore, the engine suddenly went out. Many passengers jumped from the ship, thinking that the sound of the engine had stopped because they’d hit land. Most of those souls drowned in the deep water. One woman was lost immediately; she’d jumped from the bow of the ship and the Wawaset, still having momentum, sailed right over her. Those left aboard tried to save those that had jumped by throwing boards and other loose things about the deck. The accounts of survivors tell us that this measure saved very few; the drowning passengers were too panicked to make use of it.

As the Wawaset drifted nearer to shore, there were many aboard who could not wait for the safety of shallow water; fire forced them off. Women, in particular, struggled to reach the water as their clothing was more vulnerable to stray flames; many perished in the fire. There were few who escaped entirely unscathed from the Wawaset disaster; most survivors suffered severe burns.

Even when the Wawaset grounded and came to a dead stop, the trouble was not over. People on the bow of the boat could jump to the safety of water five feet deep, it luckily being low tide, but people on the stern were still trapped between the fire and nine feet of water. The rear of the ship also held the rudder and the rudder ropes, all of which frantic passengers attempted to cling to escape death. Steward Charles Tolson, who also sought temporary safety on the rudder, had this to say about what he saw at the stern, as recorded in the Evening Star:

During the time he was on the rudder some six women caught hold of the chain, and were pulled off by others trying to save themselves; that the screams and cries were so pitiful that it nearly made him frantic, but he could do nothing. The coals began to fall on his head, and the smoke and flames forced him off…

That scene was not an uncommon one, nearly every survivor had a similar story. Miss Kate M’Pherson reported seeing “four little children hanging by their hands on the waist of the steamer, and one after the other drop into the water, the flames driving them off.”

A great many jumped over with their children in their arms; some whole families were lost this way. A lucky few were able to grab onto crates of peaches that had either spilled from the ship or been thrown overboard. Some were additionally rescued by boats that arrived at the last second by a second steamer responding to the Wawaset’s distress, the National. Unfortunately, the National arrived too late to avoid the task of retrieving bodies and ferrying them up to D.C. The task of dragging for bodies would be shared by many vessels in the coming days.

The scene back in Washington was heart-wrenching as more and more bodies were brought back for identification. The police commandeered a building by the wharf for the purpose, and escorted friends and relatives past a guard to have a look at the corpses. The agony of those who had lost loved ones was “fearful to witness” and even the crowds who had simply come to gawk felt great sorrow at the sight.

If there was a silver lining it’s that half of the passengers did survive the ordeal. Additionally, there were heartwarming accounts of heroism aboard the ship, mostly from the experienced crew. A later inquiry into the disaster not only found the captain and crew free of negligence, but the brave sailors were also commended. Each stayed aboard the ship for as long as they were able, attempting to douse the fire. When the heat forced them off, the sailors helped passengers in the water reach shore.

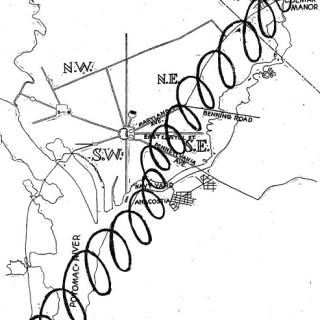

Though the sinking of the Wawaset faded from regional memory, divers rediscovered the wreck 250 yards offshore from King George’s County in 2010. The King George County Historical Society dedicated a small monument to memorialize the event.

Sources:

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 09 Aug. 1873. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1873-08-09/ed-1/seq-1/>

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 11 Aug. 1873. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1873-08-11/ed-1/seq-1/>

“Wawaset Memorial – On The Potomac.” Virginia Council of Chapters of the Military Officers Association of America.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)