The Demise of DC's Streetcars

In a previous blog post, we told you about the history of the District's original streetcar system, which dated back to the 1860s when the coaches were pulled by horses. After going electric in the last decade of the 19th century, the streetcars quickly became a crucial part of transportation in the nation's capital, just as they were in other cities across the country.

But Washington's system — which gradually coalesced from a hodgepodge of small companies into a single entity, the sprawling Capital Transit Co. in 1933 — faced special problems. One dilemma was Congress' insistence that the power source be buried underground between the tracks. That made the system especially vulnerable to snow, ice, and summertime heat expansion of the metal slots into which the cars' plows were plugged in, which sometimes prevented them from drawing power and led to congestion-causing breakdowns. "The Demands of routine maintenance were relentless," transportation historian Robert C. Post writes. "Jammed plows were an everyday occurrence, and renewing trackwork was a truly formidable undertaking," because laborers had to make repairs beneath street level.

Another, even more difficult dilemma was financial. For years, Capital Transit was run by a board of local directors who built up a cash reserve and paid only small dividends to investors, which kept the company in strong financial shape but depressed the value of its shares. After federal antitrust regulators forced another big utility company to divest its stake in Capital Transit, the company turned into a tempting takeover target for a group of investors led by shipbuilding and movie business entrepreneur Louis Wolfson. They snapped up a controlling interest in the company for a mere $20 a share in 1949 and then proceeded to tap into the case to pay investors — including themselves — big dividends that exceeded the company's profits. By 1955, they'd burned through a $6.7 million treasury, reducing it to $2.7 million, and realized a 170% return on their investment.

Unfortunately, the owners pursued this strategy at a time when the system's ridership starting to decline, due to the rising popularity of cars in the Washington suburbs. Transportation historian Zachary M. Schrag notes that in 1948, just before Wolfson took over, Washington area residents owned 203,000 automobiles. By 1955, the number was up to 418,000. During that same period, the number of mass transit commuter trips declined by 39,000 a day. In addition, the composition of the customers began to shift, with well-to-do suburbanites staying away and the seats increasingly filled by schoolchildren and the poor.

As much as the resulting revenue shortfall hurt Capital Transit, it was endangered even more by worsening labor relations. Local 689 of the Amalgamated Association of Street, Electric Railway & Motor Coach Employees of America, which represented the streetcar workforce, had long bristled over the company's big cash surplus. Workers felt that they'd been shortchanged when gasoline rationing had packed the streetcars during World War II, and wage freezes had kept them from sharing in the profits. In 1945, the workers had gone on strike for three days, eventually prompting then-President Harry Truman to seize control of the company, ostensibly for reasons of national security.

The new owners had an even rougher relationship with the union, in part because they took a hard line in negotiations and refused to include an arbitration clause in their contract, according to Schrag. In 1951, 3,400 workers again abruptly walked out on strike over seniority rules, wages, pensions, and working conditions, plunging the nation's capital into what the Associated Press called "the biggest traffic jam in its history." The wire service reported the streets descended into chaos, with motorists, desperate to find parking places, leaving their cars parked in the middle of the streets where the streetcars normally ran. Additionally, "they parked in no-parking zones, headed their cars the wrong way, (and) blithely ignored fire plugs," the article noted. Since the company also provided the city bus service, there weren't any other public transit options.

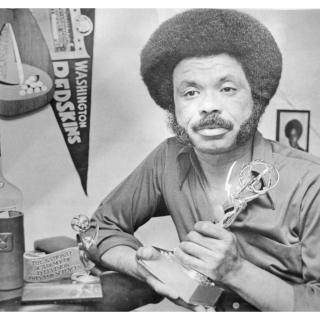

In the spring and summer of 1955, things got even worse. The District's Public Utilities Commission rejected Capital Transit's request for a fare increase so when executives began negotiating a new contract with the union in May, they had no new cash to put in to pay raises. On July 1, the union, which wanted a wage hike of 25 cents an hour, responded by walking out. This time, though, the strike lasted for seven brutal weeks, during which commuters struggled to find a way to their jobs, while Congress and the District's commissioners tried to pressure the intransigent Wolfson into giving some ground. After he defiantly dared the Senate's District Committee to revoke his franchise, Congress had enough. Democratic Oregon Sen. Wayne Morse, who denounced Wolfson as an "economic carpetbagger," introduced a bill to repeal Capital Transit's federally-approved charter, which was then passed by Congress. The District then set about finding a new owner. (Washington commuters eventually got their vengeance when Wolfson was convicted in 1967 of unrelated federal securities law violations and sentenced to a year in prison.)

The problem was that nobody wanted to take over Capital Transit, since there didn't seem to be a future in streetcar lines. After months of searching, the District's commissioners finally found the oddly-named O. Roy Chalk, a New York-based investor-entrepreneur whose eclectic interests over the years included Trans Caribbean Airways, a rail line that hauled bananas in Central America, and the Spanish-language newspaper El Diario-La Prensa. To buy Capital Transit, Chalk only had to put up $500,000 in his own money, borrowing the remaining $13 million from banks and the previous owners. Chalk worked out the deal with the assistance of Col. Gordon Moore, a retired Army officer who happened to be the brother-in-law of President Dwight Eisenhower (a connection that was brought to light by muckraking columnist Drew Pearson).

But the District commissioners imposed one condition upon Chalk. They wanted him to get rid of the streetcars, and convert the transit system entirely to buses, according to Schrag. Chalk, who around that time also unsuccessfully made a bid to take over New York City's subway system, tried to sway them. But buses seemed more modern and more compatible with an increasingly automobile-centric region.

As a farewell gesture to the city, children were allowed to ride free on Saturday, January 27, 1962, if accompanied by a paying adult. So many residents brought their kids to see a vanishing piece of local history that the company had to put 27 additional cars into service to accommodate them all. In the end, the operators also brought out a relic, an old-fashioned wooden trolley that dated back to 1919. As the AP observed, "black crepe was draped across the front and a funeral wreath was hung over the headlight."

Shortly after 2 a.m. on Sunday, January 28, the last Capital Transit streetcar finished its run and was taken off the tracks. It was the end of an era in Washington.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)