Sunday Baseball Comes to D.C., 1918

Spending a Sunday afternoon at the ol’ ballpark is pretty commonplace nowadays. But 100 years ago? Not so much.

In the early 1900s, debate raged about whether it was appropriate – or, for that matter, legal – for ballclubs to suit up on Sundays. Blue laws in many states put severe restrictions on what could and could not be done/consumed/enjoyed/observed on the traditional day of rest.

In the District, regulations stipulated that “no public exhibition of any entertainment, play, opera, circus, animals, gymnastics, game, dance or dances, or vaudeville performance of any kind, except the exhibition of moving or other pictures, vocal or instrumental concerts, artist or artists, not in character costume, lectures, and speeches” could take place on Sunday.[1]

But, in 1913, despite the law on the books, Washington Nationals fans presented a petition with 5,000 signatures to team officials asking that the club start playing games on Sundays. The petition argued that the early start time of games during the week (remember—this was before night baseball) made it difficult for Federal employees to attend without using their precious vacation days. And, when the government clerk-fans did take afternoons off to head to the ballpark, “work cannot be well handled when men are splitting days instead of taking a week or more at one time for vacational purposes.”[2] So, in essence, baseball was a drain on government efficiency.

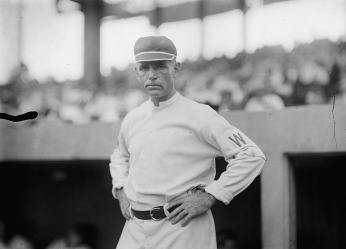

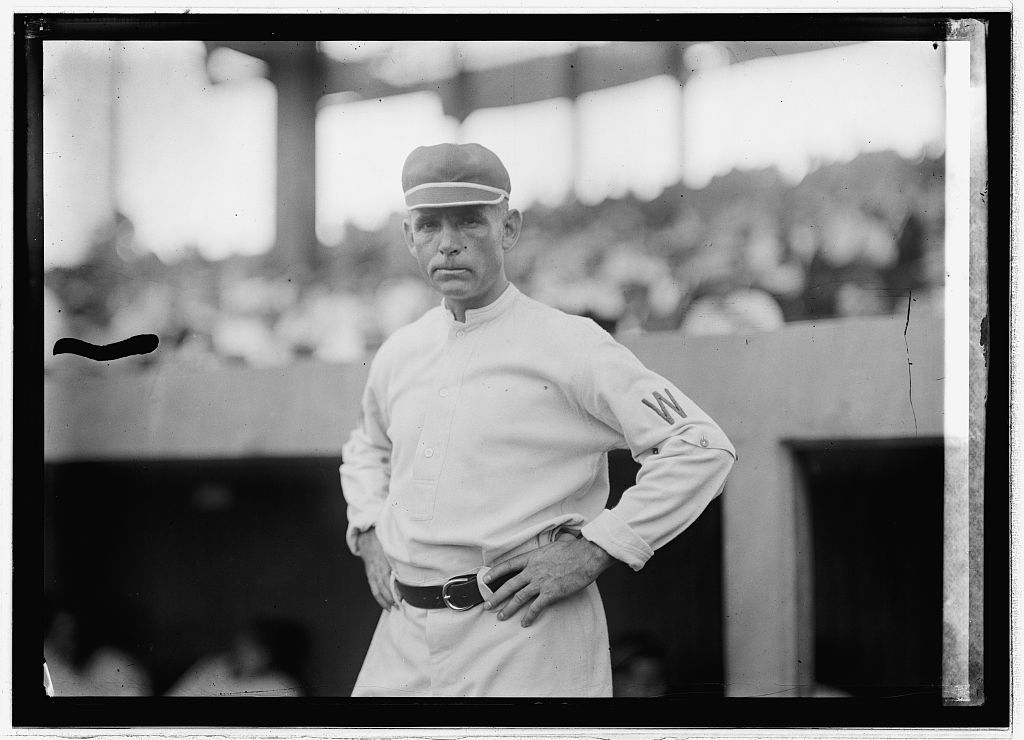

Then Nationals Manager Clark Griffith, who would later own the team, expressed his support for the idea to The Washington Post:

Personally, I would like to see Sunday baseball introduced here, and if it were given a trial, I feel that much of the prejudice of the game on Sunday would disappear…. As all the games would be started after church services are over, there would be no conflict in the matter, and if the demand for the games is strong enough I would favor giving them a trial.[3]

Other team officials, however, were hesitant – even though the Nationals stood to make a considerable amount of money and the legal authority of the City Commissioners to prohibit Sunday amusements was murky. In fact, the regulation against Sunday amusements was challenged in the courts in 1914 and briefly overturned, but the Nationals decided against scheduling Sunday games out of fear it would alienate church-going fans.

Indeed, most area ministers were staunchly opposed to the idea of playing ball on Sundays. In the words of Rev. George A. Miller, pastor of the Ninth Street Christian Church, the proposal represented a big step “toward Sunday desecration.”[4]

The ministers and like minded followers were successful in pushing off Sunday amusements, including baseball, for several more years. However, when America entered World War I, the culture in Washington, D.C. began to change quickly. Soldiers and government workers flocked to the nation’s capital and, as Episcopal Bishop Alfred Harding lamented, “Our formally serene and quiet Washington has become a city overrun with a vast influx of people.”[5]

“Wandering and aimless crowds filling the streets on Sundays, with no place to go and few amusement places open for them,” became a big problem according to The Washington Post. Police linked the lack of Sunday entertainment options to “a great increase in the illicit sale of liquor in Washington and the consequent demoralization of soldiers and civilians in the city.”[6] Not a good scene, considering that many were looking at D.C. to become a model dry city for the nation. (Wishful thinking.)

Authorities came to believe that playing baseball on Sundays would help keep residents on the straight-and-narrow. And so, on May, 14, 1918, the ban on Sunday baseball in D.C. was lifted.

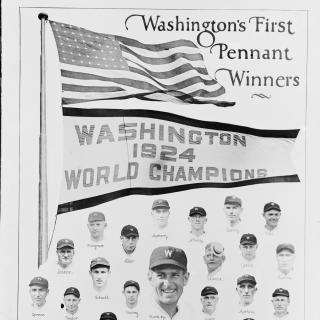

Five days later the Nats hosted the Cleveland Indians in the District’s first Sunday game. 17,000 spectators packed Griffith Stadium (then called “American League Park”) and enjoyed a dramatic, 1-0 victory by the home team in extra innings. It was the largest crowd in the stadium’s history to that point, and included some 2,000 soldiers, who were guests of the club, several Senators and a Supreme Court justice.[7]

Sunday baseball in D.C. was here to stay.

Footnotes

- ^ “Amusement Men Begin Fight on Sunday Restrictions,” The Washington Post, 20 May 1914, p. 16.

- ^ “Fans Ask Sunday Baseball in a Petition to Nationals,” The Washington Post, 29 Mar 1913, p. 8.

- ^ “Clark Griffith in Favor of Sunday Baseball Here,” The Washington Post, 30 Mar 1913, p. S1.

- ^ “Oppose Sunday Games,” The Washington Post, 25 May 1914, p. 9.

- ^ “Deplores Work Here on Sunday,” The Washington Post, 16 May 1918, p. 9.

- ^ “Yanks May Start Sunday Ball Here,” The Washington Post, 15 May 1918, p. 10.

- ^ “Yanks May Start Sunday Ball Here,” The Washington Post, 15 May 1918, p. 10.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)