The Dangerous Ghosts of WWI Research in Spring Valley

On January 7, 1993, an alarming headline greeted readers of The Washington Post: “25 HOUSES EVACUATED AS WWI SHELLS EXAMINED.” The previous day, a backhoe operator digging a trench in the Spring Valley neighborhood of Northwest Washington had uncovered a suspicious object. The construction company called the D.C. Fire Department… who called the police… who called the bomb squad. Within hours, 25 homes in the upscale neighborhood had been temporarily evacuated as munitions crews from the Army Technical Escort Unit at Aberdeen Proving Grounds investigated. Their verdict? The objects were unexploded mortar and artillery shells – and there might be more in the area.[1]

The neighborhood, long a popular spot for leaders of government to reside, was rattled in the wake of the discovery, which awakened the ghosts of World War I and an old agreement between American University and the United States Army.[2]

The year was 1916, and the Great War had raged on for nearly two years, with multiple countries involved in its conflicts. While the United States had managed to avoid becoming directly involved, the rising tensions made that option less and less viable as time went on. Even before President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917, the stories rising out of the European trenches caused major concern. A new weapon had been introduced into the battlefields: chemical gases.[3]

Though first researched by the French, the Germans had been the first to put chemical gases into action during the war in 1915.[4] The attacks were “the first major escalation of gas warfare and the start of the conflict’s chemical arms race,”[5] according to writer Theo Emery. Indeed, after seeing the harmful effects of what the gases could do – burning, blisters, respiratory damage, blindness, death – other nations hurried to understand what they were coming up against and looked to develop devastating chemical weapons of their own.[6]

With the United States getting closer to war, their interest in chemical gases meant not only developing new technology, but also testing it in order to make sure it worked. Wanting to keep every scientist and employee in one area, the Army decided to make Washington D.C. its center of activity.[7] It was, after all, the mainframe for the nation’s war effort.

But, while theoretically convenient, finding a place to actually conduct the experiments proved challenging. The Army needed a site that was large enough for testing and, at the same time, away from the public. After all, if the tests were successful, they could put anyone in close proximity in danger. In a city like Washington, it was a difficult needle to thread.

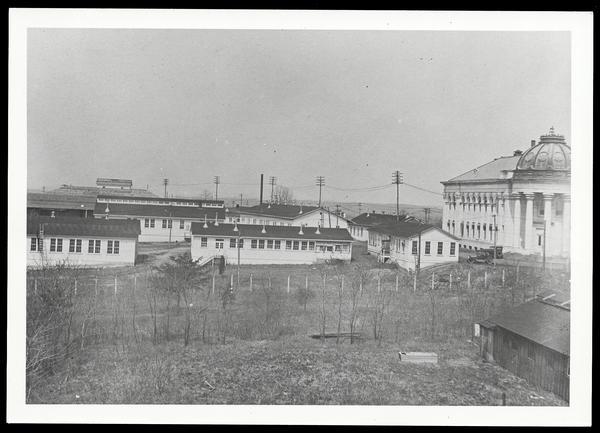

Before long, officials identified the campus of fledgling American University as their best option. Having just opened in 1914, the university had a very small student population. The onset of World War I had hindered student enrollment, and the possibility of a draft would decrease young men’s admission to universities even further.[8] In addition, the university only admitted graduate students at the time. The “still largely undeveloped campus” provided some of the key needs of the military, and the lack of people and buildings in the area made it easier to settle in quickly.[9]

With few options for their campus, the board of trustees reached an agreement with the Army for the land to be used for research purposes.[10] The school’s aspirations for becoming a premier university would be put on hold. Despite the change in direction for the campus, students and faculty alike accepted the idea that the decision could help in the fight against the Central powers.[11]

What resulted was the site first known as Camp American University, later officially known as Camp Leach. Its main projects included chemical experiments, testing, and training for support in the war effort. Testing included firing projectiles on a range; skin tests on soldiers; trying new, more effective gas masks, and more.[12]

Among the most lethal projects developed at the Camp was lewisite, also known as the “dew of death,” which had the potential to be deadly, even in small doses.[13] The scientist credited with its creation, Winford Lee Lewis, had purified the compound after a doctoral candidate at his university’s experiment created a mixture that sent the student to the hospital.[14]

The United States planned on using Lewisite to capitulate German forces.[15] However, as it turned out, peace came before the dew of death was ever used in combat. Still, it remained controversial in the post-war years as chemical weapons were widely condemned. Speaking after the war about his involvement at Camp Leach, Lewis recalled, “’I have been cussed and discussed by my colleagues and cajoled and flattered and upbraided generally.’”[16]

In the years after the war, scientists and certain Army personnel argued for the continued usage of the Camp Leach site. Scientists invested in their projects argued that their work had been “important enough to warrant permanent retention” of their laboratories.[17] However, Major General W. M. Black reasoned, presciently, in 1918 that “such investigations might prove dangerous to the growing number of residents of one of the District of Columbia’s most beautiful and healthful suburbs and would certainly hurt the area’s property values and development.”[18] Without support from the War department and government, the once first-priority experiments would have to conclude, and all personnel were required to leave.

Cleanup efforts were not well documented though, from what information is available, and the process was very rudimentary. According to Army records from 1921, contaminated land “impregnated with mustard and other toxic gases that their removal would be dangerous were burned instead.”[19] An American University publication that same year reported that "Permission was given to go far back on the university acres, to dig a pit . . . bury the munitions there, and cover them up to wait until the elements shall melt with fervent heat."[20]

Other buildings, structures, and anything else related to the research station were destroyed, and the area was left for further development and expansion, both by private homes and American University. As far as anyone could tell, the clean-up process was meant to be the last time that the Army would need to conduct any business on the land.

After the Army’s departure, the development of the University’s campus and the surrounding neighborhoods accelerated throughout the mid-20th century, with more residents occupying land formerly used as the testing site.

The first homes in Spring Valley went up for sale in 1928, and the neighborhood grew into “one of D.C.’s most prestigious neighborhoods,” home to future presidents and Supreme Court justices amongst others.[21] While the neighborhood blossomed, developers, construction workers, and residents made some odd discoveries at the work sites.

As former resident Lauren Mara Miller described to Washingtonian magazine in 2013, her childhood experience in Spring Valley included going "treasure-hunting” in neighborhood construction sites. Strange to her then, she would often have to go home to her mother because her eyes and skin stung afterwards.[22] However, these incidents stayed under the radar for the most part.

That all changed when the backhoe turned up the munitions in 1993. The area’s past as a chemical weapons testing was thrown out in the open, along with questions about what else might be lurking underground – and the risks for neighborhood residents.

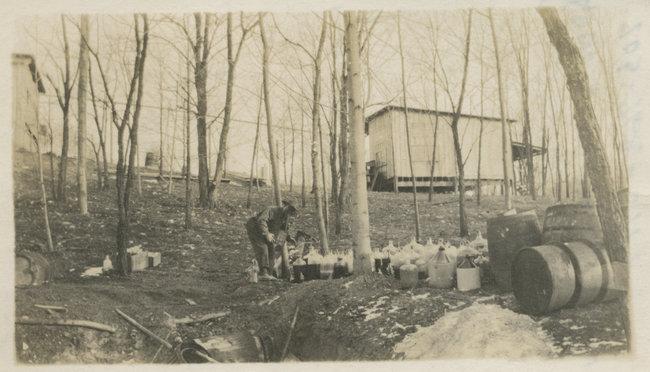

Initially, the result was a two-year study by the Army Corps of Engineers and the Environmental Protection Agency, and the removal of hundreds of pieces of buried ordnance. Officials did their best to quell fears and the initial studies seemed positive. In 1995 and again in 1996 Army reviews determined that no chemical weapons that required action remained. However, as the federal government was preparing to give the area a clean bill of health, the District’s Health Department pushed for more investigation and offered some alarming new evidence in the form of some grainy 1918 photographs.[23]

The photos had been passed down to Addie Ruth Maurer Olson whose father, Charles, had been an Army Sgt. at Camp Leach during World War I. One particularly frightening picture showed a soldier – presumably Charles – standing with canisters at the edge of a pit. On the back, Charles had written, “The Pit, the most feared and respected place in the grounds. The bottles are full of mustard to be destroyed here. In Death Valley. The hole called Hades. You know me?”[24] According to Olson, the site made such an impression on her father that he would not go near it late in his life.[25] (Sgt. Maurer died in 1980 and is buried in Alexandria.)

But where was the Hades pit, exactly? No one seemed to know.

The Army Corps launched a more in-depth investigation of the area, and no house was deemed off-limits. In 1996, a search began at 4835 Glenbrook Rd, home of American University’s president, after a landscaper uncovered some bottles containing chemicals.[26] Around the same time, other crews began digging at the nearby South Korean ambassador’s home, with even more evidence of Camp Leach discovered there. It seemed as though clean-up workers were following the trail to the elusive Hades pit.

To the horror of Tom and Kathi Loughlin, the homeowners at 4825 Glenbrook Rd, that trail led to their backdoor. Soil samples revealed that the levels of arsenic, which had been used in many of the chemical agents concocted at Camp Leach, were far above safe levels. Worse, officials suspected that the Loughlin’s home might actually sit atop the Hades pit – a disturbing thought considering they had watched hundreds of munitions, bottles and drums be unearthed from surrounding properties.

Fortunately for the family, a buy-back clause they had negotiated in 1994, when the house was first built, allowed them to sell the property back to the developers and leave in 2000.[27] Though, as writer Theo Emery has detailed, the impacts of the experience still resonate.

With the family out of the home, the Army Corps continued excavation at 4825 Glenbrook Rd. Neighbors concerned for their safety asked the Army Corps for relocations and updates. Others informed them of medical issues many residents faced across time and space in Spring Valley. The large tents, warning systems, constant presence of workers, and the media attention did not seem to help with the thought of an ever-present threat.

After years of excavation, the Army Corps decided that the only way to be certain that the land was safe was to completely demolish the structure in 2012. Post-demolition, workers continued removing contaminated soil, disposing of any remaining munitions, and re-filling the lot with clean, chemical-free soil. No chemical leaks exposed neighbors to harmful agents during the excavation but in 2017 seven workers were exposed and hospitalized.[28]

The actual clean-up ended in 2020, but the property wouldn’t be turned back over to American University until November 2021 due to final touches like leveling the property and final soil re-filling.[29] After two decades of excavation and cleaning, the now-empty lot looks as if it was never disturbed.

If you're curious about what workers faced everyday while working on-site, the Army Corps of Engineers made this video to explain their process:

Aside from 4825 Glenbrook Rd, the Army Corps of Engineers tested over 1,600 other properties in Spring Valley for elevated levels of arsenic and determined that 177 of them required remediation. In addition, the Corps identified 92 properties with possible buried ordnance. Remediation is ongoing and expected to be complete in the next several years.[30]

It seems that, for many, the ghost of Camp Leach won’t go away easily.

Footnotes

- ^ Thomas-Lester, Avis and Brooke Masters, “25 HOUSES EVACUATED AS WWI SHELLS EXAMINED.” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 7 January 1993. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1993/01/07/25-houses-evacu…

- ^ Willis, Haisten, “Spring Valley: Haven for the elite has walkability, diversity and now, places to eat.” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 11 August 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/realestate/spring-valley-haven-for-the-e…

- ^ Gross, Daniel. “Chemical Warfare: From the European Battlefield to the American Laboratory.” Science History Institute, published 14 April 2015, https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/magazine/chemical-warfare-…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Emery, Theo. “’History is Repeating Itself:’ A Century of Chemical Warfare.” The Alicia Patterson Foundation, updated 24 March 2021. https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/history-repeating-itself-century-ch…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Gross, Daniel. “Chemical Warfare: From the European Battlefield to the American Laboratory.” Science History Institute, published 14 April 2015, https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/magazine/chemical-warfare-…

- ^ Emery, Theo. Hellfire Boys: The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service and the Race for the World’s Deadliest Weapons. Little, Brown, 2017

- ^ “AU History.” American University, accessed 1 February 2022. https://www.american.edu/about/history.cfm

- ^ Gordon, Martin, Barry Sude, Ruth Ann Overbeck, and Charles Hendricks. “A Brief History of the American University Experiment Station and U.S. Navy Bomb Disposal School, American University.” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, June 1994, https://www.nab.usace.army.mil/Portals/63/docs/SpringValley/AUES_Report…

- ^ Emery, Theo. Hellfire Boys: The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service and the Race for the World’s Deadliest Weapons. Little, Brown, 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Martin, Barry Sude, Ruth Ann Overbeck, and Charles Hendricks. “A Brief History of the American University Experiment Station and U.S. Navy Bomb Disposal School, American University.” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, June 1994, https://www.nab.usace.army.mil/Portals/63/docs/SpringValley/AUES_Report…

- ^ Emery, Theo. “’History is Repeating Itself:’ A Century of Chemical Warfare.” The Alicia Patterson Foundation, updated 24 March 2021, https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/history-repeating-itself-century-ch…

- ^ Emery, Theo. “The Scientists Who Created America’s War Gases.” The Alicia Patterson Foundation, updated 31 March 2021, https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/scientists-who-created-america’s-war-gases

- ^ Emery, Theo. “The Chemists’ War.” The New York Times, (New York City, NY), 10 November 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/10/science/chemical-weapons-world-war-1…

- ^ Emery, Theo. “The Scientist Who Created America’s War Gases.” The Alicia Patterson Foundation, updated 31 March 2021, https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/scientists-who-created-america’s-war-gases

- ^ Gordon, Martin, Barry Sude, Ruth Ann Overbeck, and Charles Hendricks. “A Brief History of the American University Experiment Station and U.S. Navy Bomb Disposal School, American University.” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, June 1994. https://www.nab.usace.army.mil/Portals/63/docs/SpringValley/AUES_Report…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Vogel, Steve. “Evidence of D.C. Toxins Unheeded; New Findings Back ’86 Warning to U.S. on Buried Weapons,” The Washington Post (Washington, D.C.), 9 July 2001.

- ^ Jaffe, Harry. “The Toxic Waste Pit Next Door.” The Washingtonian, published 28 February 2013. https://www.washingtonian.com/2013/02/28/the-toxic-waste-pit-next-door/

- ^ ibid. While Miller’s experiences confused her as a child, as an adult she realized that her and her friends had most likely been finding munitions connected to Camp Leach. Without knowing it, she had been exposed to the chemicals in the developing neighborhood along with her friends.

- ^ Vogel, Steve. “Search to Resume near AU for WWI Chemicals,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 24 January 1999. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1999/01/24/search-to-resum…

- ^ ”Sgt. Maurer Burial Pit.” US Army Corps of Engineers, accessed 8 Feb 2022. https://www.usace.army.mil/Media/Images/igphoto/2000745896/

- ^ Emery, Theo. "Zeroing In on Mystery of an Old Site Called Hades.” The New York Times, (New York City, NY), 17 March 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/us/hunt-zeros-in-on-the-mystery-of-a…

- ^ Emery, Theo. “The House Over Hades.” The Alicia Patterson Foundation, updated 16 August 2018. https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/house-over-hades

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Auguenstein, Neal. “WWI chemical munitions cleanup ‘is complete’ under former Northwest DC home.” WTOPnews, published 13 August 2020. https://wtop.com/dc/2020/08/wwi-chemical-munitions-cleanup-is-complete-…

- ^ Fenston, Jacob. “Cleanup Complete at WWI Chemical Weapons Dump in D.C.’s Spring Valley.” DCist, published 26 November 2021, https://dcist.com/story/21/11/26/cleanup-complete-chemical-weapons-dump…

- ^ ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)