Just Stick It in the Basement: Before the Archives

Today, the founding documents of America - the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights - are on display at the Charters of Freedom exhibit in the Rotunda of the National Archives. Tourists from across America and the world make pilgrimages to see the most revered documents in American history. Extensive preservation measures have been put in place, with each document placed in bullet-proof[1] titanium cases filled with noble, non-reactive argon gas,[2] to protect them from the wear and tear of the elements, or from Nicholas Cage-inspired treasure hunters (see right).

The Charters’ cases contain a mechanism to retract the documents back down into a 22-foot-deep bunker at a moment’s notice. The documents are even examined by a $3.3 million monitoring system, designed by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, so that signs of damage can be detected far before they could be by the human eye.[3]

But this wasn’t always the case. For most of our nation’s history, these charters, now considered priceless, were kept with the United States’ other government documents - that is, shoved wherever officials could find space. Before the National Archives was founded in 1934, these documents were stored essentially at random.

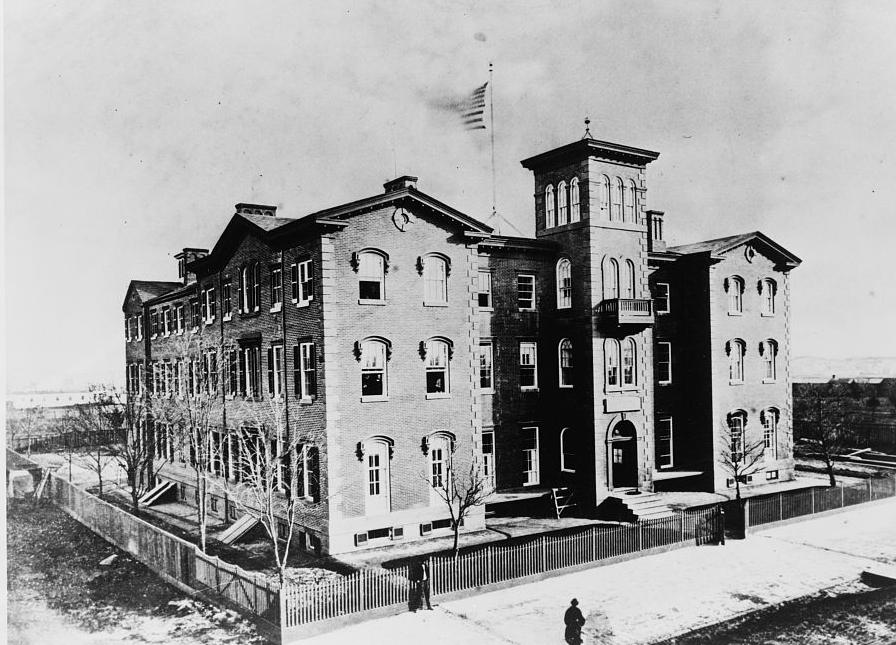

For instance, initially, there was no real plan for preserving the Constitution. After its approval by the Continental Congress in 1787, it was kept for a few years by the secretary of the Constitutional Convention, Roger Alden. It passed briefly into the hands of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, after which it was shuttled from unremarkable storage building to unremarkable storage building for years. In 1814, when government officials and documents were being evacuated from Washington ahead of the advancing British army, the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were unceremoniously stuffed in a sack along with assorted other documents and tossed on a cart. The Constitution spent the next century being shoved into storage space. It returned to the North Wing of the Treasury for forty years, and then spent an eleven-year stint at the Washington Orphan Asylum;[4] from 1875 until 1921, the Constitution sat in the State Department’s basement, until it was finally moved to a place of honor in the Library of Congress.[5]

This was not at all uncommon; the careless handling of the Constitution is characteristic of the United States’ treatment of historic documents for many years. The Declaration of Independence was tacked on a wall in the Patent Office, in direct sunlight, for several decades; repeated copies caused it to fade, so that even by 1814, when it was shoved in that bag, it already looked worn.[6] Copies of the Declaration made using a wet-pressing process in 1823 further damaged the original.[6] At one point, in 1940, someone even attempted to repair a tear with Scotch tape, which, in time, “turned the color of molasses and had itself to be carefully removed.”[7]

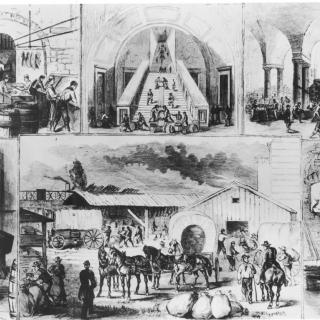

Most government documents were part of this pattern of astonishingly haphazard record-keeping; many documents in the Archives’ Department of Justice files today, for instance, are heavily charcoal-stained because they were kept next to a coal-burning stove for many years. Each government department kept its own archive, and so the documents that are housed in the modern-day National Archives were divided between the Departments of State, War, Justice, the Treasury, the Interior, the Navy, Commerce and Labor, Agriculture, and the Land Office, among others.[8] With federal records totaling 1.03 million cubic feet by 1916, it was an extremely difficult task for researchers to find anything they were looking for.[9] Different types of records were located in different buildings, and many records were not available to researchers at all, or were simply lost.

In 1912, historian and archivist Waldo Gifford Leland[10] deplored the situation in the American Historical Review:

“[N]o Government has more signally failed in the fundamental and...imperative duty of preserving and rendering accessible to the student the first and foremost of all the sources of the nation’s history, the national archives...[Documents] have been stored wherever space could be found for them. Thus they are in cellars and subcellars, and under terraces, in attics and over porticos, in corridors and closed-up doorways, piled in heaps upon the floor, or crowded into alcoves: this, if they are not farmed out and stored in such rented structures as abandoned car barns, storage warehouses, deserted theaters...Nor do the records in current use fare much better. They are, whenever that is possible, a little nearer the clerks who must consult them, but the line of demarcation between the current and uncurrent records is not a sharp one and the former are gradually absorbed into the mass of the latter.”[11]

The disorganization made it almost impossible for researchers to find records, and often poor conditions (such as being kept in a hot attic or near a boiler pipe) caused documents to deteriorate. (Some volumes in the Library of Congress, for a time in 1861-2, had been damaged by bakery soot.) Leland also reported having found “hundreds of volumes covered with mold and literally soaked through” in the archives of the Senate, which were located under a terrace, and that the carelessness with which documents had been piled up had made many government buildings into fire hazards.[12]

This proved to be prescient, as in 1921 a fire at the Commerce Building damaged and destroyed numerous records, including 99% of the 1890 census, not least because of the fact that the firemen had sprayed gallons upon gallons of water into the record room to put out the blaze. The damage was compounded by the fact that, since the fire occurred at the end of the workday, once it had been extinguished, everyone simply went home, leaving the records in ankle-deep water overnight. Eventually, the remaining, damaged records were actually ordered destroyed by the Library of Congress in 1933. Out of the nearly 63 million people counted, records for barely over 6,000 remain. The destruction of the 1890 census has been frustrating genealogists for decades, not to mention incurring the ire of the public at the time.[13]

That same year, largely spurred by this disaster and the public outrage that followed, President Warren G. Harding ordered the Declaration and Constitution transferred to the Library of Congress, and steps to be taken to found a national document archive. This measure was not actually passed until 1926, and ground was not broken on the Archives until 1931, but at the speed of government, that’s impressive enough.[14] In 1934, the National Archives officially opened, and the ever-growing pile of federal records finally had a single home. Eighteen years later, after one last detour to Fort Knox, the Declaration and Constitution followed, to be encased in their current gas-sealed shrine.[2]

The more systematic keeping of records in the modern-day Archives has made things much easier for researchers, and now the National Archives, in its multiple locations, boast the most visited research rooms in the world. The Archives, however, are filling up. The sheer volume of papers that government agencies generate annually necessitated the founding of a new, bigger “Archives II” in College Park, MD, in 1994. Even so, there is already almost no room left in the new Archives, and Congress has delayed plans for an Archives III. Let’s hope that lawmakers find a solution soon, or we'll have to go back to the days of storing documents in basements and hallways.

Footnotes

- ^ To my knowledge, no one has yet tried to shoot the Constitution, although I admire the Archives’ proactive stance on document preservation.

- a, b National Archives, “The Declaration of Independence: A History,” last accessed July 31, 2015, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_history.html

- ^ Pauline Meier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), x.

- ^ The Treasury building had moved some of their documents to the Asylum in the 1860s after the North Wing had been demolished. https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/buildings/section26

- ^ Michael G. Kammen, A Machine That Would Go of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture, (Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1986), 73.

- a, b Pauline Meier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), xi.

- ^ Ibid., xii. National Archives, “The Declaration of Independence: A History,” last accessed July 31, 2015, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_history.html

- ^ Waldo Gifford Leland, “The National Archives: A Programme,” American Historical Review 18, no. 1 (October 1912): 7-9.

- ^ Donald R. McCoy, The National Archives: America’s Ministry of Documents 1934-1968, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1978).

- ^ Who has an award named after him, by the way, in case that lends his testimony more weight.

- ^ Leland, “The National Archives: A Programme,” 5, 10. The practice of storing archival material wherever space can be found has not quite died out, as there are a significant number of archives stored in a cave system near Kansas City. Fortunately, the indexing system has progressed past “pile it on the floor”.

- ^ Leland, “The National Archives,” 11.

- ^ Kellee Blake, “First in the Path of the Firemen,” National Archives, last accessed July 31, 2015, http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1996/spring/1890-census-1.html

- ^ McCoy, The National Archives, 6. The process spanned four presidents - Warren G. Harding ordered the Archives created, the act was passed with President Calvin Coolidge’s support, ground was broken under Herbert Hoover, and the Archives were opened under Franklin D. Roosevelt.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)