The Wright Brothers Prove Their Worth in Arlington and College Park

Ohio and North Carolina often get into a dispute about who can “claim” the Wright Brothers. The former was where the two lived and conducted most of their research, but the latter was where they actually took to the air for the first time. The debate rages on, with shots fired in forms from commemorative coins to license plates.

But the place where the Wright Brothers really fathered the American aviation age was right here in the DC area, where they taught the first military pilots to fly, proved to the American public that their machine was real, and took to the air at what is now the oldest airport in the world.

The Wright Brothers made their first flight on that famous beach in Kitty Hawk, NC, in December 1903. They made numerous other flights in 1904, gaining confidence with each trial. But for years, the Wrights’ experiments were discredited by the aviation experts of the day. They considered the brothers’ results too good to be true, and the Wrights’ reluctance to show people their airplane, fearing patent theft, certainly didn’t help convince anyone that they were anything more than con artists. The overblown claims of newspapers after their first flight - that they could fly “three miles at a time”[1] at “express train velocities”[2] - may have caused the Wrights’ actual achievements to seem disappointing in comparison. For years, when they would invite the press to see flights of their airplane, nobody came. Even an article in 1906, which acknowledged the importance of their discoveries with regards to pilot control, still referred to the mystery of flight as something that would be solved in the future.[3]

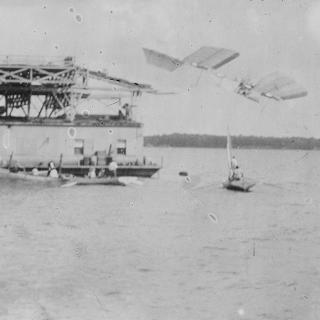

Residents of the District were quite familiar with inventors claiming to have solved the mystery of flight. Two months before the Wrights’ successful flight, they had seen the Smithsonian-backed Langley Aerodrome,[4] a project that had the respect of the aeronautical community and $50,000 of government funding[5] behind it, plunge into the Potomac within seconds. Understandably, people were considerably more skeptical of the claims of two unknown bicycle makers from Dayton.

However, this all began to change in late 1907. When the French and German governments began to show interest in the Wrights’ plane, the U.S. government finally decided to make its move. The Wrights had reached out to the government two years before, but they had been rejected. After the Wrights’ successful flights in France in 1908, the Department of War signed the Wrights for a contract, and commissioned the first army airplane, alternately called Signal Corps No. 1 and the Wright Military Flyer.

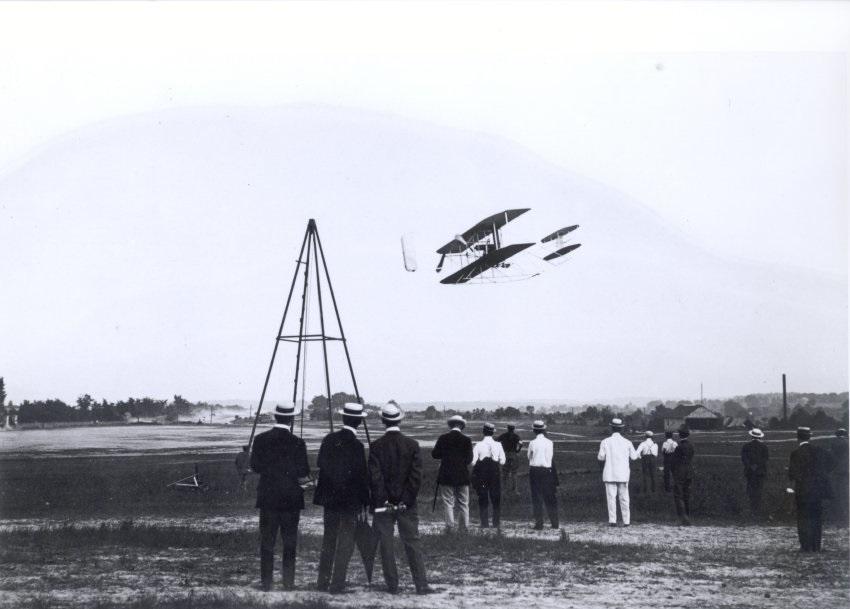

The Wrights would prove their machine’s qualifications at Fort Myer, a military base in Arlington County, VA. They met or exceeded all of the Army’s specifications, including flying at 40 miles per hour, carrying a combined passenger weight of 350 pounds, maneuvering in any direction in the air, landing without damage, and flying for at least an hour non-stop, which was a world record at the time.[6]

Video of a test at Ft. Myer, on July 27, 1909. Orville Wright is the pilot and Lt. Frank Lahm is the passenger. President Taft, his wife, and a crowd of others are in attendance.

The Wright brothers, however, hated Ft. Myer. The field was much too small to make any kind of significant maneuver, with only enough space to fly straight for at most a few hundred yards before being in danger of hitting the surrounding buildings and tall trees.[7] The crowds that the Wrights could never draw before flocked to Ft. Myer in the thousands; President Taft became a frequent spectator, and the flight ground became a popular picnic site for the upper crust. Needless to say, the Wright brothers were not happy about this further obstruction. Ft. Myer’s commander was not a big fan of the Wright brothers, either; the fort’s primary purpose was as a cavalry base, and the noise from the airplane spooked the horses.

In light of this, the Signal Corps sent Lt. Frank Lahm to search for a new, more suitable site through hot-air balloon flights (as was then the state of the art in aerial reconnaissance).[8]

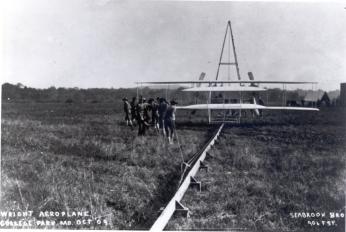

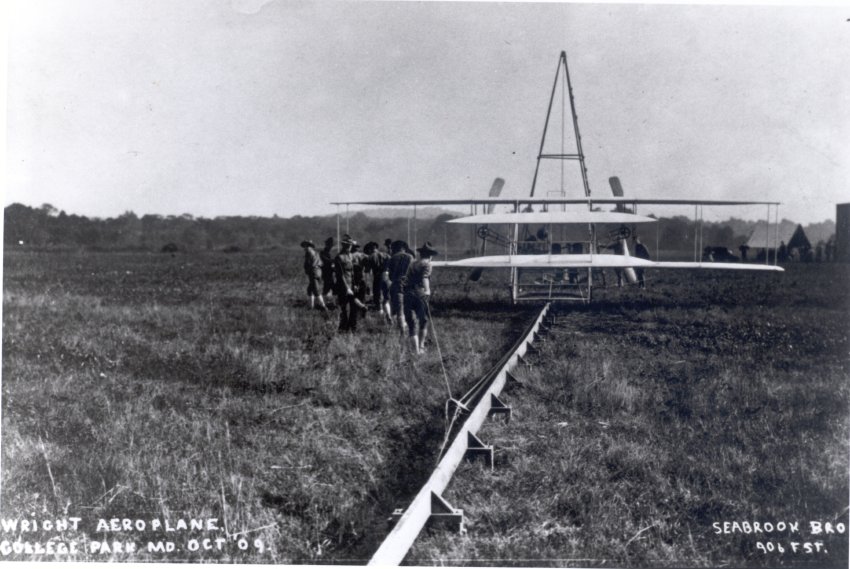

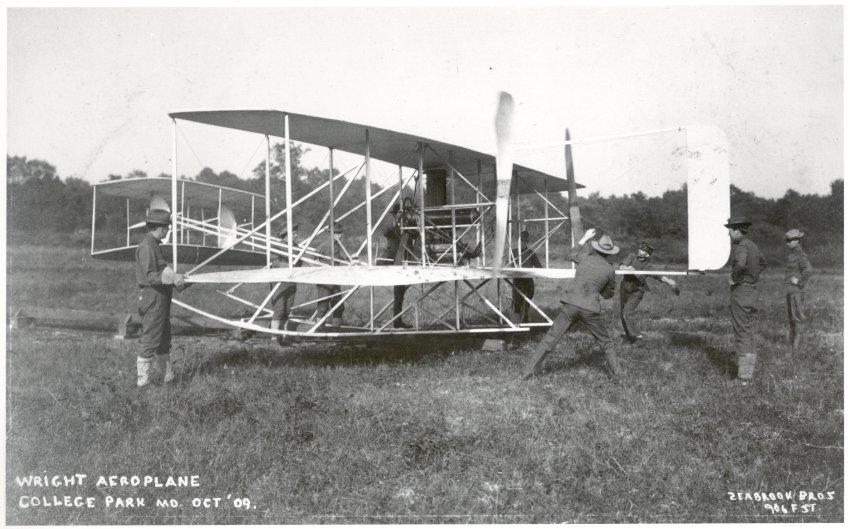

The Army selected a 160-acre field in College Park, close to the Maryland Agricultural College,[9] as the site for further testing, leasing it from a farmer on August 25, 1909. College Park was chosen for its proximity to the railroad tracks, making it easy to transport necessary material and personnel to the site, as well as the relative distance from more urban Washington, D.C., making for fewer obstructions and (they hoped) fewer spectators. Even moving to College Park, however, did not fully dissuade the crowds of flight-watchers, with visitors showing up despite the eight-mile rail journey to the airfield.

The final part of the Wrights’ contract specified that they had to train two Army men to fly their machine. Lieutenants Lahm and Benjamin D. Foulois were chosen to be the first officers to be trained by Wright, but due to Foulois’ selection for the International Congress of Aeronautics in France, he was replaced by Lt. Frederic E. Humphreys of the Corps of Engineers.[10]

Wilbur Wright was to train the pilots; Orville was in Berlin at the time, demonstrating their Flyer to the German government. Wilbur first took to the air with his students on October 8, 1909, and over the course of four weeks, taught them to maneuver and land the plane, as well as how to coast to the ground with a dead engine. On October 26, Humphreys and Lahm flew solo for the first time. While at College Park, Wilbur also repeated several of Orville’s experiments from Berlin, as well as determining that the machine could lift itself from the starting rail under its own power, which it did for the first time; previously, they used a catapult-like device with a heavy weight to provide enough momentum for the Flyer to start.[11]

Once Wilbur had finished training Lahm and Humphreys, he gave the returning Foulois a total of 54 minutes of flight time, before Lahm and Humphreys crashed the plane on November 5, ending military flights for several months. Lahm and Humphreys, however, had to return to their divisions, leaving the undertrained Foulois the only military pilot.[12]

After a year and a half of inactivity, during which time Foulois had to teach himself to fly, the Army opened a flight school at College Park in 1911, where four army officers and 15 engineers convened to learn to operate four planes (two Wright B models, two Curtiss models, and one Burgess-Wright).[13] Over the next two years, hangars were built on the current site of the College Park Metro, although the modern hangars stand about a half-mile away, and more land was purchased to expand the airfield to 200 acres.[14]

However, College Park’s snowy winters proved to be a problem for flying during colder months, and so the school would migrate south to Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, TX until the weather improved back in College Park. This was a very cumbersome and inconvenient process, and so eventually, in 1912, the flight school moved permanently to California.

Even when the military flight school moved away, however, College Park remained an active airport, hosting further aviation experiments, serving as a base for some government aircraft, and opening to the public for flights of private planes. The College Park airport was the site of a host of other “firsts,” including the first woman in America to fly in a plane (1909),[15] the first machine gun fired from an airplane (1912),[16] the departure of the first airmail flight (1918),[17] the first controlled helicopter flight (1924),[18] and the first blind landing using only instruments (1931).[19] The airport is still active today, making it the oldest continuously operational airport in the world, and a few times a day, airplanes rise from the same ground on which America’s first pilots learned to fly over a hundred years ago.

More Information

This article wouldn’t have been possible without the invaluable research assistance of Ameena Mohammad and Scott Allen of the College Park Aviation Museum. Even though the airport is still active, there is a fairly sizable Smithsonian-affiliated museum on its grounds, with exhibits about the history of the airport and aviation. It’s definitely worth a visit, especially given that the museum features an animatronic Wilbur Wright, who polishes a propeller at you while he gives you a friendly rundown of the airport’s early history.

More on the Wright brothers’ struggle for recognition and their tour of Europe: http://generalaviationnews.com/2011/05/09/fliers-or-liars/

Footnotes

- ^ “Flying Machine Soars 3 Miles…,” Virginian-Pilot, December 18, 1903.

- ^ “Aerial Navigation Exhibit by Santos Dumont and Other Scientists to be Given in New York,” Evening Star, January 4, 1906.

- ^ “Darius Green’s Progeny: Progress Made Toward the Navigation of the Air,” Evening Star, February 4, 1906.

- ^ Piloted by Langley’s chief research assistant, Charles M. Manly (no, really).

- ^ $1.3 million today.

- ^ The fort was also the site of a more unfortunate first - the first fatality from an airplane crash. On September 17, 1908, Orville was flying with Lt. Thomas Selfridge when the plane’s propeller struck part of the rudder. In the ensuing crash, Lt. Selfridge was killed and Orville was severely injured. The trials were delayed several months to allow Orville time to heal. [http://tinyurl.com/cpairporthistory; Charles deForest Chandler, How Our Army Grew Wings: Airmen and Aircraft Before 1914, (New York: Ronald Press Company, 1943), 154.]

- ^ Charles deForest Chandler, How Our Army Grew Wings: Airmen and Aircraft Before 1914, (New York: Ronald Press Company, 1943), 152.

- ^ Chandler, How Our Army Grew Wings, 162.

- ^ Who would eventually host Wilbur and several Army officers for a luncheon. Chandler,How Our Army Grew Wings, 164.

- ^ Chandler, How Our Army Grew Wings, 163. It’s rumored that the real reason that Foulois was transferred was that he was too enthusiastic about promoting the airplane for the army’s liking.

- ^ Chandler, How Our Army Grew Wings, 163-4.

- ^ Meghan Cunningham, ed., The Logbook of Signal Corps No. 1: The U.S. Army’s First Airplane, (Government Printing Office, 2004), 5-6.

- ^ During this time, New York bicycle maker Glenn Curtiss had built and patented a rival airplane design, which the Army had also purchased.

- ^ Over the course of the training, the airport was also the site of two more fatal crashes, both of which killed both passengers. [College Park Aviation Museum, “Army Signal Corps Aviation School,” last accessed July 27, 2015,http://www.collegeparkaviationmuseum.com/About_Us/History/Army_Signal_Co...

- ^ Mrs. Sarah Van Damen, wife of visiting Cpt. Ralph Van Damen, was Wilbur Wright’s passenger. (In May 1909, the Fort Worth Star-Telegramactually reported that Annabelle Whitford, star of Ziegfield’s “Follies of 1909,” had beaten Mrs. Van Damen to the punch by finding a flying machine on the ground and blundering her way into a flight over New York City and back, blown by the wind. This level of hardball journalism was somewhat characteristic of early coverage of flight. [“Young Woman’s Perilous Ride in Aeroplane,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 10, 1909.])

- ^ The gunner, by the way, was Cpt. Charles deForest Chandler, author of How Our Army Grew Wings, the book that is so frequently referenced above.

- ^ College Park Aviation Museum, “Radio Navigation Aids,” last accessed July 27, 2015, http://www.collegeparkaviationmuseum.com/About_Us/History/Airmail.htm

- ^ College Park Aviation Museum, “Radio Navigation Aids,” last accessed July 27, 2015, http://www.collegeparkaviationmuseum.com/About_Us/History/Berliners.htm

- ^ James Kinney accomplished this feat while the National Bureau of Standards was testing radio navigation at College Park. (College Park Aviation Museum, “Radio Navigation Aids,” last accessed July 23, 2015,http://www.collegeparkaviationmuseum.com/About_Us/History/Radio_Navigation_Aids.htm.)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)