"And Other Bloody Happenings": Rosslyn and the Dangers of Dead Man's Hollow

“No locality in the vicinity of Washington can boast of so many mysteries as ‘Dead Man’s Hollow.’ It begins just beyond Rosslyn, where Spy Run crosses the river road to Falls Church, and is about a mile in length, being a tortuous ravine, through which the little stream runs on its way to the river…But for the terror-inspiring history of the hollow, the drive would be romantic and picturesque. As it is, however, many hesitate to go that way even in the daytime, unless in company, while at night only the bravest men run the gauntlet of bad men and weird shapes popularly supposed to be met with there.” – The Washington Post, July 30, 1895.[1]

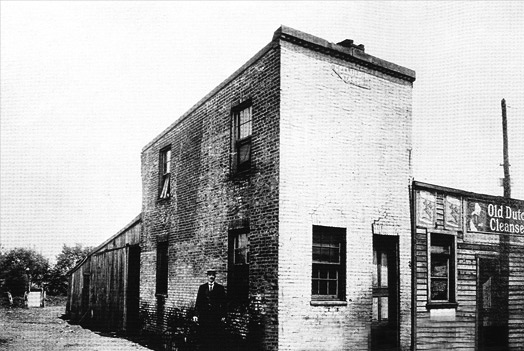

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the Virginian outskirts of Washington were very different from the modern communities that now exist in Arlington. Rosslyn was a notorious den of gambling and prostitution awash in alcohol, while the nearby ravine known as Dead Man’s Hollow was a site of murder, robbery, assault and suicide.

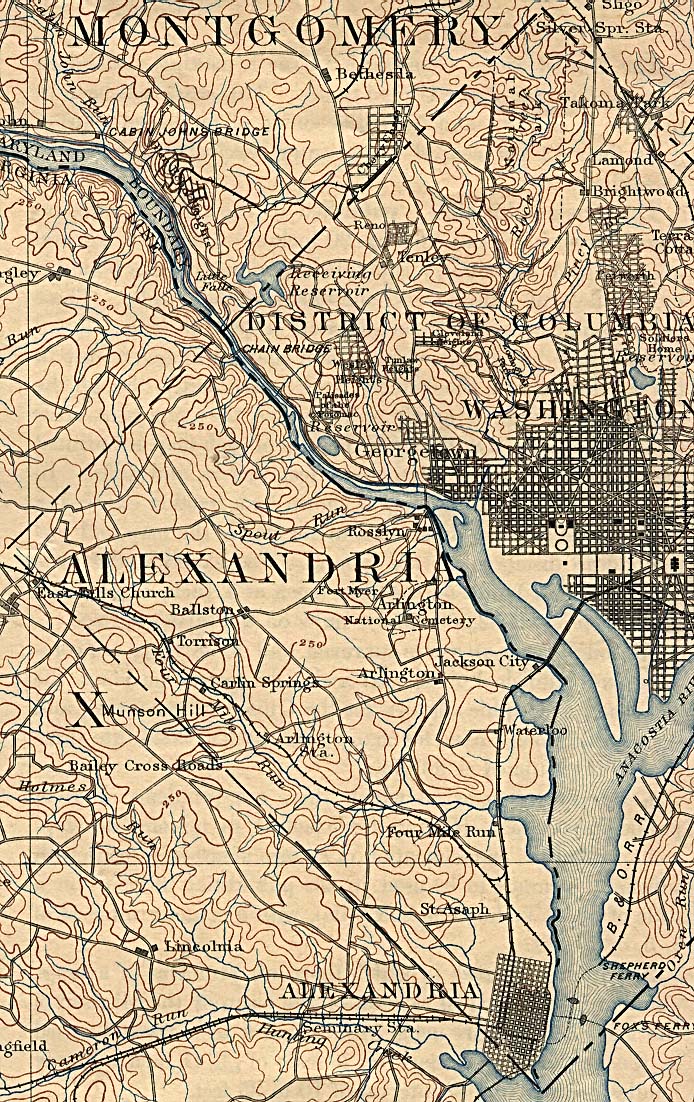

During the American Civil War, Federal soldiers were stationed in Arlington in three forts, and much of the existing civilian population fled from the area. The name Rosslyn, after one family who held property, first appears in an 1865 map illustrating the wartime defenses of Washington. Following the end of the American Civil War, soldiers remained encamped in the vicinity, prolonging the wartime atmosphere of the town. Union soldiers were stationed at Fort Whipple, which was renamed Fort Myer in 1881.

Some of these soldiers were regular visitors at the Old Bachelor Roadhouse, a brothel located near the entrance of the fort. What had been fields and farmland before the war became increasingly dominated by businesses that offered opportunities for vice and violence, including saloons, brothels, and gambling houses. In 1903, a riot would break out at Gary’s Sunday bar and gambling house after a soldier was shot nearby. Following the shooting, hundreds of soldiers later arrived and wrecked the establishment in retaliation.[2]

In 1903, the Good Citizens’ League for Alexandria County chose a new candidate for Commonwealth’s Attorney, with the intention of having Rosslyn and Dead Man’s Hollow cleared. For both moral and economic reasons, these citizens sought to improve the area, and they chose Crandal Mackey as the man for the job.

In 1904, Mackey took office, and soon took action, recruiting a group of a dozen men and meeting them in DC near the Long Bridge. Riding together on a trolley line to Rosslyn, he equipped them with axes, guns and sledgehammers for a day raid on Rosslyn’s vice district. They smashed their way through saloons and gambling halls, destroying equipment, furniture, bottles of alcohol, and paintings they viewed as “obscene.” While only successful in arresting six men that day in Rosslyn and Jackson City, the raids were a dramatic act that put Arlington’s red-light districts on notice.[3]

Yet even while Mackey would be successful in clearing Rosslyn and Jackson City, Dead Man’s Hollow remained a location known for murder and tragedy. Documented within local newspapers were numerous crimes, solved and unsolved, which took place in the confines of the hollow.[4]

Evidence of the prevailing racial attitudes of the time, the violence was often attributed to unknown colored men, as was the case in the shooting October 1896 shooting of William McClure. Following the attack on McClure, the Baltimore Sun reported on local feeling in a Special Dispatch. “Intense excitement prevailed in the locality, and a party has surrounded the woods in which the colored man is supposed to be concealed. It is intended to lynch him if he can be found."[5] The alleged assailant was never found and the anticipated lynching never took place.[6]

The Washington Post reported extensively upon the murders, shootings, stabbings and other assaults that took place near Dead Man’s Hollow between 1880 and 1910. Reporting on the murder of Fred Miles in 1906, the newspaper discussed the haunting atmosphere of this quiet ravine.

“With such a grewsome (sic) record to intimidate the wayfarer, the Hollow, whose deathlike silence in the daytime is broken by naught save the murmuring of a shallow stream, and is disturbed by nothing at night save the lonely hoot of a stray owl, is looked upon with apprehension by the stray pedestrian or rider who is forced to enter its lonely confines."[7]

For Arlingtonians who grew up in the area, the ravine’s reputation for violence made a deep impression. As, Frank Ball, who had been a supporter of Mackey as a young man, recalled decades later: “Some committed suicide, some were killed by the gamblers and liquor people, some got in fights and a little bit of everything happened. I would not have gone up Dead Man’s Hollow after dark for all the money in the world."[8]

As time passed, tighter law enforcement gradually lowered the crime levels around Rosslyn and fewer bodies turned up in the hollow. Still, the area remained dangerous for other reasons. Automobile accidents injured many drivers and passengers, including Crandal Mackey himself, along with his family. In August 1912, Mackey drove his car into Dead Man’s Hollow after being blinded by the lights of another driver, resulting in minor injuries for his wife and two daughters and the fracturing of his shoulder.[9] In 1923, Arlington County placed a new strong wooden fence and a series of danger signs onto the nearby highway in order to prevent cars from skidding into the Hollow.[10]

Footnotes

- ^ A PLACE OF MYSTERIES. (1895, Jul 30). The Washington Post (1877-1922)

- ^ Shotgun Justice: One Prosecutor's Crusade Against Crime & Corruption in Alexandria and Arlington by Michael Lee Pope

- ^ The Nation's Capital Brewmaster: Christian Heurich and His Brewery, 1842-1956 By Mark Elliott Benbow

- ^ BULLET TAKEN FROM MULLEN. (1907, Oct 08). The Washington Post (1877-1922)

- ^ Special Dispatch to the,Baltimore Sun. (1896, Oct 17). SHOT BY A COLORED MAN.The Sun (1837-1992)

- ^ DEAD MAN'S HOLLOW ROBBER. (1896, Oct 18). The Washington Post (1877-1922)

- ^ DEAD MAN'S HOLLOW IS AGAIN SCENE OF TRAGEDY. (1906, Jul 25). The Washington Post

- ^ The Pentagon: A History By Steve Vogel

- ^ HURT IN AUTO'S FALL. (1912, Aug 08). The Washington

- ^ ARLINGTON COUNTY, BUREAU OF THE POST, Falls Church, Va tel Falls,Church 104. (1923, Jul 19). MOVES TO BUY PARK AS TOWN HALL SITE IN FALLS CHURCH, VA. The Washington Post

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)