Then There Were No Coffins: The 1918 Influenza Epidemic Hits Washington

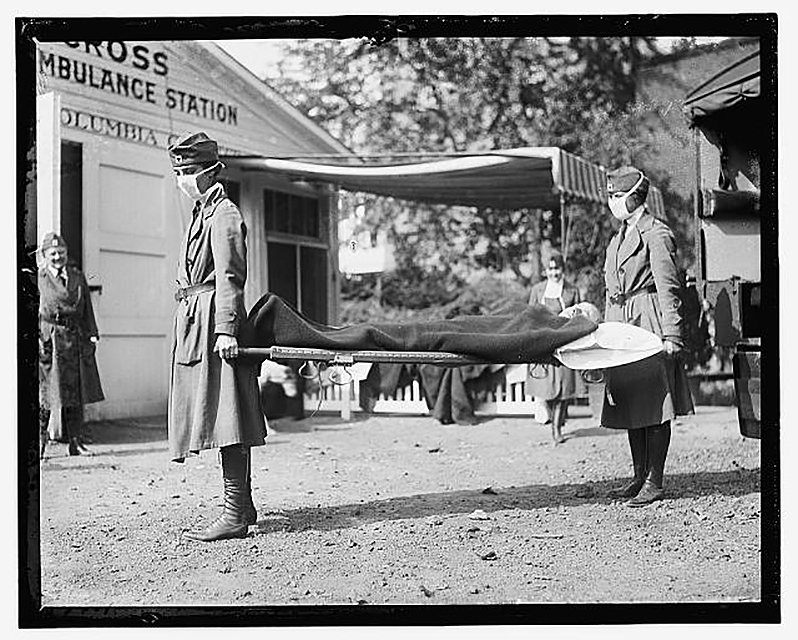

Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1918 was a ghastly place. The First World War was in its final days. In the city itself, a deadly influenza epidemic raged. Entire families were wiped out; some people died within a day of showing symptoms. “That’s how quickly it happened,” William H. Sardo, Jr., of Chevy Chase, recalled in a 2006 Associated Press article. “They disappeared from the face of the earth.”[1]

Ten days after the first reported death, at the beginning of October, city officials decided to act. On October 4, they required that all cases of the flu be reported to the Board of Health.[2] Calling influenza a “crowd disease,” they emptied the city of congestion.[3] They banned all large public gatherings. Federal agencies staggered working hours. Schools were shut down, churches closed.[4]

But no matter what these officials did, the death toll kept rising. By October 14, there were too many patients for available physicians to handle. Every hospital bed in the city got filled.[5]

This massive wave of cases came with an especially macabre task for city officials. They had to figure out what to do with the bodies. With a cremation rate of just 3.7% (today that number is closer to 40%), that wasn’t going to be easy.[6]

As the death toll rose during the epidemic, the city struggled to find people who were able and willing to bury the victims. Many of the gravediggers employed by the city were likely sick themselves; others, out of fear, refused to inter people who had died of the flu.[7]

Without gravediggers, the coffins remained above ground, in funeral homes and cemetery vaults. Sardo, whose father was a funeral director, remembered pine caskets stacked up in his family’s living room.[8]

William C. Fowler, the District health officer, had to come up with a solution. First, he hoped that he could convince people to work temporarily as gravediggers. In a statement that was printed in The Washington Post, Fowler begged for help, even offering to pay the volunteers. “There are 20 bodies of influenze [sic] victims in the vault at one cemetery and fifteen in another because of the want of gravediggers,” Fowler said. “Laborers will be well paid, and will at the same time perform a public service, if they will volunteer to me for this work at once.”[9]

But the gravediggers, out of fear, did not come.

Fowler had a second plan, one that would be highly controversial today. First, he had some Marines from the Quantico Marine Base serve as gravediggers. Then, to get enough people for the job, he found a population that couldn’t refuse to work: prisoners. With a group from Occoquan Prison, Fowler was close to dealing with the bodies.[10]

The coffins in the cemetery vaults now went into the ground to be buried. Those who died did not get a proper funeral — as a public health measure, public funerals were also prohibited by the city — but their bodies did get inhumed.[11]

Still, Fowler’s corpse-related problems were not over. With the country involved in a total war and up to 72 people dying in the city in a single day, the number of available coffins ran low. Around October 10, the city ran out. Bodies piled up in morgues, without anywhere to put them.[12]

Health officials put up calls to nearby cities, hoping one of them had available coffins. But none of them did. Baltimore, too, had a coffin shortage.[13] So did Philadelphia.[14]

Desperate, health officials came up with a questionable solution. If they couldn’t get cities to donate coffins, they would figure out a way to reroute a shipment toward D.C. — even if it was headed to another city that needed them.

According to Louis Brownlow, the D.C. Commissioner, health officials discovered two train cars filled with coffins headed on the Potomac railroad toward Pittsburgh. (Pittsburgh also had a coffin shortage at the time.)[15] The Board of Health mandated that the coffins be rerouted to the D.C. city hospital.[16] And so, around October 17, two train cars filled with a total of 270 coffins headed to D.C.[17]

With that, Fowler seemed to have solved his burial problems. But there was one catch. The coffin industry in the past month had followed simple economic principles: as the supply fell and the demand rose, the price skyrocketed. On October 13, an editorial in The Washington Post ripped into the so-called “coffin trust” that was “holding the people of the city by the throat and extorting from them outrageous prices for coffins and the disposal of the dead.”[18]

There was one thing left for Fowler to do. He required that all coffins be sent to him, and he sold them at a fixed price.[19] On October 21, Fowler and other health officials took to fixing D.C.’s burial problem. “All day long [that day] the coffins were distributed, the graves were dug, and the victims were buried,” Brownlow wrote.[20]

A few weeks later, the influenza epidemic was over. Churches opened, funeral services resumed, and people stopped having trouble finding coffins. The horror of the war, too, was about to end.

With the end of the war would come an end to Fowler’s immense power, as well. According to Brownlow, he was only able to procure the coffins and set their prices by using “the absolute power of the War Industrial Board.” The end of the war meant an end to that power.[21]

Life in the city was about to return to normal — sort of. The terror local residents got from the years of war and month of disease would never fade entirely. Every year he could, Sardo took his flu shot. “It scares the hell out of me,” he said of the disease. “It does.”[22] Sardo died in 2007.

Footnotes

- ^ “Survivors Remember 1918 Global Flu Pandemic,” Associated Press 17 December 2006.

- ^ “Ordered to Report Influenza Cases,” The Evening Star 5 October 1918.

- ^ “Washington Made Sanitary Zone to Combat Influenza,” The Evening Star 3 October 1918.

- ^ Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, Year Ended June 30, 1919, Vol. III: Report of the Health Officer (Washington, D.C.: 1919), 16.

- ^ Louis Brownlow, A Passion for Anonymity (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1955), 70-1.

- ^ Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, 15.

- ^ At least this was the case in Philadelphia. See John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York, NY: Viking, 2004), 223.

- ^ “Survivors Remember 1918 Global Flu Pandemic,” AP.

- ^ “72 Dead From ‘Flu’,” The Washington Post 11 October 1918.

- ^ Melissa V. Clough, “The Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919 in Washington, D.C., and its Impact on Public Health Services,” 8 May 1997, George Mason University Senior History Seminar.

- ^ Annual Report of the Commissioners of Columbia, 16.

- ^ “Coffins Short in District; Aid Asked from Outside,” The Washington Post 10 October 1918.

- ^ “Wants Plain Funerals,” The Sun 19 October 1918.

- ^ “Lack of Coffins Halts Grip Victims’ Burials,” Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, PA) 4 October 1918.

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 83.

- ^ Brownlow, A Passion for Anonymity, 71.

- ^ “ ‘Flu’ Deaths Climb,” Washington Post 19 October 1918.

- ^ “The Ghoulish Coffin Trust,” The Washington Post 13 October 1918.

- ^ Brownlow, A Passion for Anonymity, 71.

- ^ Ibid., 72.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Survivors Remember 1918 Global Flu Pandemic,” AP.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)