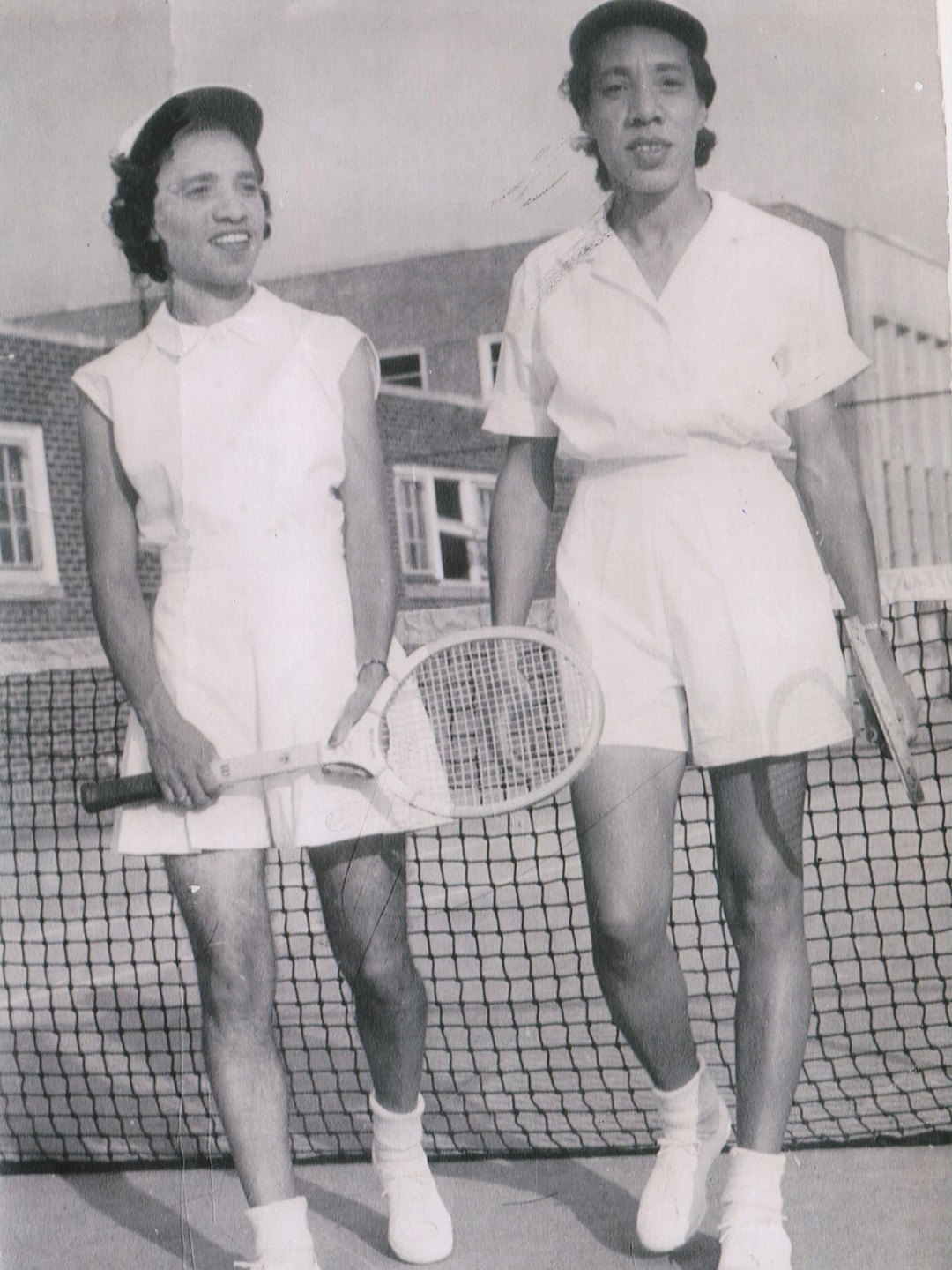

Tennis's Original Sister Act: Margaret and Roumania Peters

August 30, 1946 was an ideal day for a tennis match. The temperature was cool, the sky was clear and the sun shone brightly upon the court at Wilberforce College in Ohio.[1] An impeccably well-dressed crowd of over 3,000 spectators from all over the country – including a sizable contingent of Washingtonians – anxiously awaited the start of the Women’s Championship of the American Tennis Association (ATA), the country’s preeminent all-black tennis association.[2]

The excited crowd welcomed former champion Ms. Roumania Peters (29) of Georgetown, a Tuskegee graduate, and up-and-coming star Ms. Althea Gibson (17) of New York to the court for the final. The players would not disappoint.

The match was a back-and-forth affair. Peters won the first set 6-4, but dropped the second 7-9. In the decisive third set, Peters “pushed back the fighting young threat” from Gibson, and took the championship, 6-3.[3] With the win, Peters recaptured the ATA singles title she’d first won in 1944, and added another championship to her family’s trophy case.

Indeed, from the late 1930s to the early 1950s, Roumania and her older sister Margaret dominated the black tennis circuit, at one point winning 14 doubles titles in 15 years.[4]

Born in 1915 and 1917,[5] Margaret and Roumania lived at 2710 O St. in Georgetown.[6] As teenagers, the girls taught themselves to play tennis at Georgetown’s Rose Park, spending hours every day perfecting their strokes. It was not a country club atmosphere, as Roumania recalled later: “Sand, dirt, rocks, everything. We would have to get out there in the morning and pick up the rocks and sweep the line and put some dry lime on there. That’s what we played with. We didn’t have any fancy courts. We learned there.”[7]

“Pete” (Margaret) and “Repeat” (Roumania) began playing in local tennis tournaments organized by the D.C. Municipal Playground department in the late 1920s, representing Rose Park Playground.[8] They quickly made a name for themselves.

In 1935 Cleveland Leigh Abbot offered Margaret a full scholarship to attend the prestigious Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.[9] She declined the offer at first, choosing to wait for her sister to graduate from high school the following year so they could attend college together.

In the interim, the American Tennis Association invited the Peters to participate in their first ATA national tournament in 1936. Roumania made it all the way to the finals, where she lost to three-time champion Lulu Ballard.[10]

In 1937, Margaret and Roumania began their undergraduate education and collegiate tennis careers at Tuskegee.[11]

From 1937-1941 the sisters won the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Championship and were four-time ATA National Tournament doubles Champions from 1938-1941.[12]

The Peters living room was filled with dozens of trophies, as Roumania recalled years later:

One time [Margaret] would win this tournament; the next time I’d win the tournament. Then the next time she’d win the tournament, then I’d win the next. And so on, and we kept it going like that and every year we still won the doubles. No one in college beat us in the doubles so that’s how we reviewed so many so many trophies because we’d each bring about two trophies apiece from the schools.[13]

In 1941 they graduated, each with a B.S. in Physical Education.[14]

The two young women returned to Georgetown as celebrities. Crowds gathered to see the sisters play at the Rose Park courts, they posed with movie stars, and they even played exhibition matches for British Royalty.[15] While stationed in DC during World War II actor, dancer, and singer, Gene Kelly often played tennis with the Peters sisters at Rose Park.[16]

Despite their fame and continued success on the court, the Peters faced a difficult road. Amateur tennis players (regardless of race or gender) did not receive prize money for winning tennis tournaments until the Open Era in 1968.[17] The sisters paid for their own equipment and traveling expenses, financing their careers by working as physical education teachers.[18]

Furthermore, at the time that Margaret and Roumania were at the height of their careers, tennis was strictly segregated. Even as they dominated the ATA circuit, they were denied the opportunity to compete against the leading white players of the day.

But, by the time Roumania faced off with Althea Gibson at Wilberforce in 1946, the winds of change were starting to blow in American sporting circles. In 1947, Jackie Robinson would break baseball’s color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers. A few years later, Alexandria’s Earl Lloyd made history as the first African American player in the N.B.A.

ATA officials aggressively lobbied the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association to open up tournaments to African American players, and it finally happened in 1950 when the USLTA invited Gibson to play in the U.S. National Championship at Forest Hills, New York.[19] Debuting on her 23rd birthday, Gibson would go on to win five USLTA grand slam titles. She also continued to compete in ATA events, winning an astounding 10 consecutive national titles between 1947 and 1956. (The 1946 match against Roumania Peters would be the only tennis match Gibson lost to a black woman at a major tennis competition in her career.[20]) She is widely known today as one of the greatest to ever play the game.

Conversely, by the time tennis integrated, Roumania and Margaret Peters were in their 30’s — considered to be the retirement age for elite players. As a result, they barely missed their own opportunity to make history. As Roumania's daughter, Fannie Walker Weeks put it,

"My father always said that they just came along at the wrong time but they were happy with their lives. They were happy with what tennis did for them.[21]

Indeed, after retiring from the ATA in the early 1950s, Margaret and Roumania earned master’s degrees and worked in the D.C. Public Schools, while continuing to inspire and encourage the next generation of D.C. tennis players. For twelve years, Roumania taught tennis in the Department of Recreation’s summer tennis camp at Rose Park.[22] Many of her protégés went on to receive four-year-athletic scholarships to college.[23]

Years later, the Peters sisters received overdue recognition for their athletic accomplishments. In 2003 the USTA presented the sisters with an "achievement award" and inducted them into the Mid-Atlantic Section Hall of Fame. In 2015, the DC Government officially dedicated the Rose Park Tennis Courts to Margaret and Roumania Peters.[24]

Footnotes

- ^ Lula Jones Garrett “3000 fans Add Color to the ATA Tennis Tournament” The Afro-American, 13 Aug 1946: 12.

- ^ The American Tennis Association (ATA) founded on November 30, 1916 by more than a dozen black tennis clubs is an all-black tennis association that functioned parallel to the white-only United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA). For more, see “ATA History: History of the American Tennis Association” http://www.americantennisassociation.org/ata-history/

- ^ Lula Jones Garrett “Roumania Peters Regains Women’s Crown With Win Over Challenger,” The Afro American, 31 Aug 1946:16.

- ^ Cecil Harris and Larryette Kyle-DeBose, Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis from Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe to the Williams Sisters (United States: Ivan R. Dee, 2007), p.109-110

- ^ “Peters, Margaret and Matilda Roumania,” Contemporary Black Biography Copyright 2005 Thomson Galehttp://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/peters-margaret-and-matilda-roumania

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991), p.66-69.

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991),p.66

- ^ “The Sportswoman” The Afro American 8/29/1928

- ^ Jon Krawczynski, “Trailblazing Sisters Finally Getting Their Due,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; July 20, 2003; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: St. Louis Post-Dispatch D.10 Accessed December 31, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Keith R.. "Peters, Margaret and Matilda Roumania Peters." African American National Biography, edited by Ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr.. , edited by and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. Oxford African American Studies Center, http://www.oxfordaasc.com/article/opr/t0001/e2347 (accessed Thu Feb 19 16:25:30 EST 2015).

- ^ Jon Krawczynski, “Trailblazing Sisters Finally Getting Their Due,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; July 20, 2003; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: St. Louis Post-Dispatch D.10 Accessed December 31, 2016.

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991),p.69

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991), p.68

- ^ Cecil Harris and Larryette Kyle-DeBose, Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis from Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe to the Williams Sisters (United States: Ivan R. Dee, 2007), p.110

- ^ “Roumania Peters, 85, Tennis Star in ‘40s-50s.” Newsday, Combined Editions The Washington Post, May 23, 2003. Accessed December 31, 2016.

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991), p.68

- ^ “Open Era” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tennis#Open_Era

- ^ “Roumania Peters, 85, Tennis Star in ‘40s-50s.” Newsday, Combined Editions The Washington Post, May 23, 2003. Accessed December 31, 2016.

- ^ Althea Gibson Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Althea_Gibson

- ^ Cecil Harris and Larryette Kyle-DeBose, Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis from Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe to the Williams Sisters (United States: Ivan R. Dee, 2007), p.110

- ^ Interview with Fannie Walker Weeks in "WETA Neighborhoods: Dupont Circle, Georgetown, Anacostia and Capitol Hill," 2016.

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991), p.69

- ^ Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, and Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991), p.69

- ^ Jon Krawczynski, “Trailblazing Sisters Finally Getting Their Due,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; July 20, 2003; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: St. Louis Post-Dispatch D.10 Accessed December 31, 2016.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)