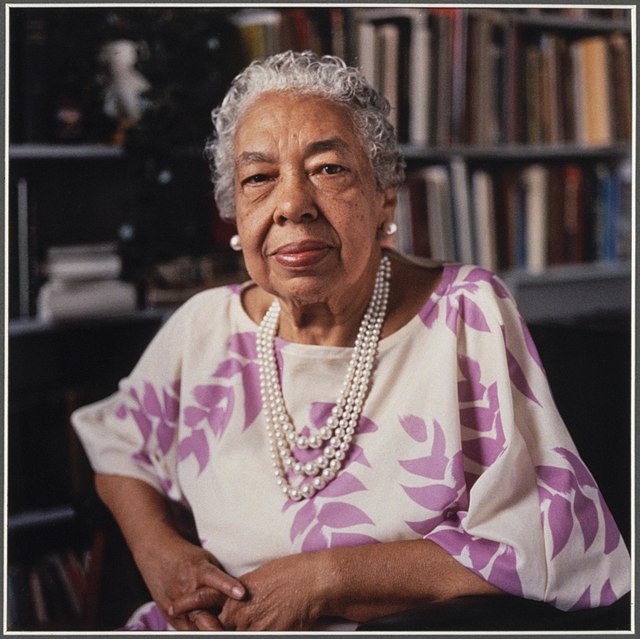

Alice Dunnigan Left Her Mark as the First Black Female White House Reporter

It was 1948. Segregation was the norm and the contemporary Civil Rights Movement had not yet taken off in the public eye. President Harry Truman was making his way across the United States on his Whistle Stop Tour, accompanied by several reporters, including one Alice Dunnigan. Dunnigan was the only Black reporter and the only female one, which at times made her a target. When the train stopped in Cheyenne, Wyoming, a military official attempted to rip Dunnigan away from the other reporters, believing her to be a bystander despite her press badge telling him otherwise. Her identity had to be proven by a fellow white reporter.[1] In this instance though, the injustice did not go unnoticed.

President Truman visited her room afterwards to apologize, an incident she recollected in her autobiography. “Truman poked his head in. I didn’t know what to do. In those days the press had awe and respect for the President. I tugged at my skirt. I couldn’t find my shoes. I knew I should be standing up. But I couldn’t move. And Truman said, very quietly, ‘I heard you had a little trouble. Well if anything else happens, please let me know.'”[2]

Unfortunately, this was not the only time Dunnigan was underestimated or treated poorly because of her race and sex. She had to fight tooth and nail for her position as a political correspondent in D.C. and even then, it was difficult. Dunnigan later explained, “Race and sex were twin strikes against me. I’m not sure which was the hardest to break down.”[3]

Dunnigan knew that she wanted to write from a young age. At just 13 years-old, her stories about her community were published in the Owensboro Enterprise, the African-American newspaper two hours away from her hometown Russellville, Kentucky.[4] Historian Michael Morrow noted: “I think this community put a lot of fight in Alice. You almost had to jump out the womb fighting here if you hoped to make it. She understood young enough that she would have to chart her own course.”[5] Before moving to D.C. in 1942, Dunnigan worked as a teacher in a segregated school system. While there, she would compile fact sheets about Black Kentuckians to ensure her students knew about the history the school didn’t teach them, exemplifying her strong belief system.[6]

Dunnigan moved to D.C. soon after the onset of World War II, following an ad for a typist job, leaving her son behind with her parents looking after him. When she got there, the administrator was shocked because he expected a white woman, not a Black one. Dunnigan got the job because the administrator could not afford to push her away. It was the first of many times she would receive shock or pushback in her time at D.C.[7]

Soon the young typist contacted Claude Barnett, the head of the Associated Negro Press (ANP), a news service which served over 100 Black newspapers across the U.S. and was incredibly influential in the Black press. Dunnigan asked Barnett if she could freelance for the agency. He agreed and she worked in that capacity until 1946, when – on an experimental basis – she was offered the job of Washington Bureau Chief for the ANP.[8] Even with the promotion, it was clear Barnett held some doubts as to Dunnigan’s capabilities to hold the job.[9]

Due to her gender, Dunnigan was often underestimated and received less pay than her male coworkers For a while, she had to pawn her pocket watch every Saturday to feed herself on the weekends and then buy it back once her paycheck came in on Monday.[10] “I was never allowed more than five dollars on it, just enough for Sunday dinner.” She recalled in her autobiography.[11] Dunnigan also struggled to gain access to the politicians she was charged to write about, as she did not have a government press pass at the time.

The first time she applied, she was denied her because the ANP was a weekly news service, not a daily one. Barnett’s sexist outlook didn’t help either. “For years we have tried to get a man accredited to the Capitol Galleries and have not succeeded. What makes you think that you–a woman–can accomplish this feat?” She remembered him saying.[12] Dunnigan never stopped trying though, and six months later, she was in. She earned a press pass to Congress, becoming the first Black reporter to do so.[13]

Her next mission was to break into the White House press pool, which Harry S. McAlpin had integrated in 1944. She and one other reporter joined him there in 1948.[14] Soon, word got around that President Truman was planning a Whistle Stop Campaign tour across the country. Dunnigan could join the other reporters, if she could pay her way (the trip was $1,000, about $10,000 now).[15] Barnett refused to help her with getting the funds for the trip, telling her “Women don’t go on trips like this.”[16] Dunnigan would prove him – and other doubters, of which there were many – wrong. She found a friend whose bank allowed her to borrow money to make the trip. As she stepped onto the train with the others, she became the first Black reporter to go on a trip with the president.[17]

Dunnigan got her first major story on that tour. It was midnight, and the train was stopped in Missoula, Montana. A curious onlooker asked Truman if Civil Rights would be part of his 1948 platform.[18] He responded: “I’ll say that civil rights is as old as the Constitution of the United States and as new as the Democratic platform of 1944.”[19] Dunnigan’s headline the next morning read “Pajama Clad President Defends Civil Rights at Midnight.”[20]

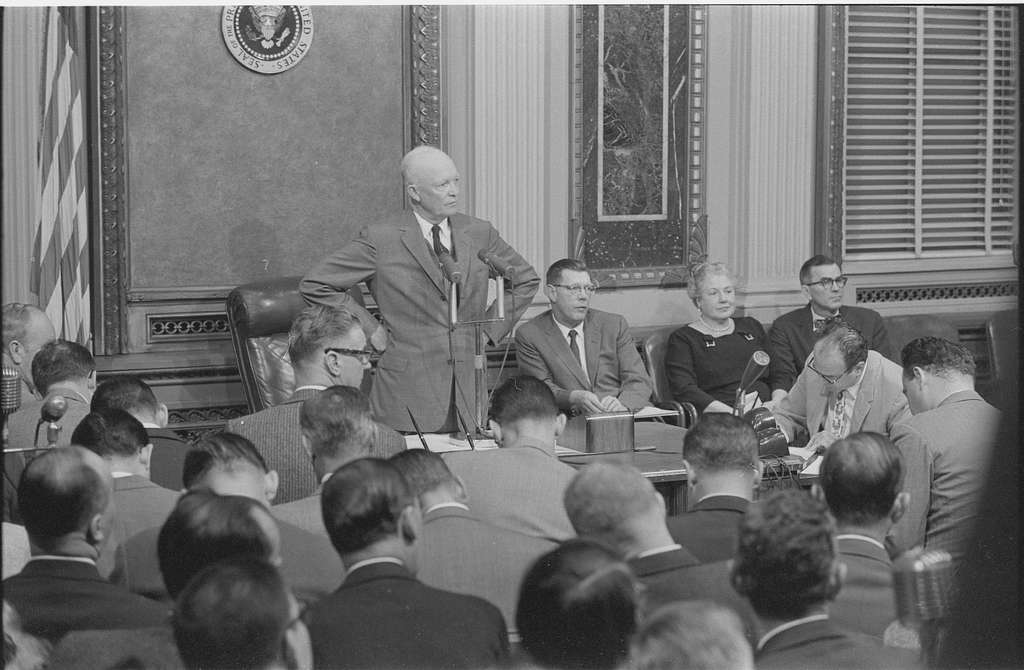

As the 1940s melted into the 1950s, Dunnigan continued to focus on civil rights, covering several events in D.C. including the sit-ins at the White Tower hamburger stand and the Greyhound terminal restaurant.[21] When Dwight Eisenhower became president in 1953, Dunnigan continued to ask provocative questions about civil rights. She said later: “I always felt a journalist should be a crusader. I went to every press conference with a loaded question. And if I got an answer or a no comment or nothing, I had a story.”[22] This approach soon led to a clash with President Eisenhower.

At Eisenhower’s first press conference, Dunnigan asked him a question about civil rights that he could not quite answer. Later, his spokesman would ask Dunnigan to have her questions screened beforehand, which Dunnigan refused because no other reporter had to be screened.[23] She faced discrimination in access to the president as well. In 1953, she couldn’t attend one of Eisenhower’s speeches inside a whites-only theater and later she had to sit in the ‘servant’s section’ at Ohio Senator Robert Taft’s funeral. Eventually Eisenhower got tired of her constant questioning and refused to call on her, a refusal that would last 2 ½ more years until the end of his presidency.[24]

“She was iced. But she kept going. She didn’t just give up. She went to every news conference.” Carol McCabe Booker, editor of Dunnigan’s autobiography, observed.[25] Other reporters noted the snub, which her fellow reporter Ethel Payne also faced. One Baltimore Afro-American article said: “Each time the President would look away to the other side of the aisle, or would recognize someone at Mrs. Dunnigan’s back, at her side, or in front, but never the ANP reporter.”[26]

Despite Eisenhower’s snub, Dunnigan continued to put out stories for the ANP, defying those who wished to silence her. After the lynching of Emmett Till, Dunnigan wrote a heart wrenchingly honest article for the Baltimore Afro-American. One section from her article reads: “One can’t help wonder how real freedom is when a 'northern' youth has his brains beaten out and his body sunk into the bottom of the deep. Why? He dared to exercise freedom of speech to a 'southern' white woman.”[27]

It wasn’t until President John F. Kennedy’s first press conference on January 25, 1961, that Dunnigan was called on again, leading to a flurry of headlines about the moment. She asked about a voting rights conflict in Tennessee, to which he responded that he would protect the voting rights of Black voters using the Civil Rights Act of 1957.[28] During Kennedy’s brief administration, Dunnigan worked for the President’s Committee on Equal Opportunity.

She continued her work under President Lyndon B. Johnson after Kennedy’s assassination and earned an award for her contributions in 1964.[29] The Chicago Defender detailed some of her accomplishments for readers: “Mrs. Dunnigan is Education Consultant to the President’s Committee on Equal Job Opportunities, having been appointed by President Johnson when he was Vice President. She is also the recipient of 25 citations for outstanding work in the field of journalism. Among the many ‘firsts’ in her notable career are these: first Negro woman to receive a White House Press Pass and first Negro woman to belong to the National Press Club (only members).”[30] She continued her advocacy work within the government until 1970, when she retired.

Though Alice Dunnigan is not a household name, her work broke open the doors for marginalized writers, something she was extremely passionate about. In the preface to her autobiography, Dunnigan wrote: “It is my fondest hope that the story of my life and work will…encourage more young writers to use their talents as a moving force in the forward march of progress and that their efforts will soon result in giving Americans the kind of nation that those of my generation so long hoped and worked for.”[31]

Alice Allison Dunnigan passed away on May 6, 1983, but her legacy still thrives.

Footnotes

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. “The Black Press: New Archive for An Embattled, Battling Institution.” The Washington Post. The Washington Post Inc. March 18, 1977.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kelly, Kate. “Alice Dunnigan: First Black Woman Reporter to Cover White House.” America Comes Alive. America Comes Alive. 2022.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Guttman, Leslie. “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.” The Washington Post. The Washington Post Inc. September 15, 2018.

- ^ Woodson, DonnaMarie. “Alice Allison Dunnigan: White House Correspondent trailblazer.” Sarah Stevenson Tuesday Forum. Sarah Stevenson. February 1, 2022.

- ^ Kelly, "Alice Dunnigan."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Guttman, “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Aykroyd, Lucas. “Alice Dunnigan, the First Black Woman Journalist to Get White House Press Credentials.” Mental Floss. Minute Media. October 21, 2020.

- ^ Kelly, "Alice Dunnigan."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Guttman, “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kelly, “Alice Dunnigan.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Guttman, “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.”

- ^ Kelly, “Alice Dunnigan.”

- ^ Trescott, “The Black Press.”

- ^ Kelly, "Alice Dunnigan."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Guttman, “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.”

- ^ "Why does Ike Snub Colored Reporters?" Afro-American (1893-), Apr 27, 1957, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Dunnigan, Alice. "What Good is Freedom if You are Dead?: Till Exercised Freedom of Speech; Now He is Dead." Afro-American (1893-), Oct 29, 1955, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Guttman, “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.”

- ^ Kelly, "Alice Dunnigan."

- ^ LBJ citizens' group to honor Alice Dunnigan. 1964. The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), Oct 24, 1964 (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Guttman, “The first black female White House reporter had to pawn her watch every week just to eat.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)