Washington's Lost Food Craze: Terrapin Soup

Before the days of Half Smokes and Jumbo Slices, D.C.’s collective stomach rumbled for a different delicacy: diamondback terrapin. The native turtle had long fed residents of the Chesapeake but by the 1830s the turtle had become one of the region’s most coveted foodstuffs and by the end of the 19th century, swanky eateries from New York to California featured turtle soup on their menus. While turtles from all over the U.S. were used to prepare this famous dish, the Chesapeake Diamondback was undoubtedly the turtle of choice.

Today, the diamondback is an important regional symbol. The endemic turtle was declared Maryland’s state reptile in 1994 and has been The University of Maryland’s mascot since 1933.[1] However, the very name of the turtle references its longstanding status as food. In her book, Diamonds in the Marsh: A Natural History of the Diamondback Terrapin, Biologist Barbara Brennessel writes:

[The terrapin] gets its name from Native American sources. In the 1600’s, it was called “torope” by Virginia Algonqiuans, “turepe” by the Abenakis, and “turpen” by the Delawares. Roughly translated, the name means edible or good tasting turtle.[2]

While Native Americans introduced colonists to the “good tasting turtle,” it soon fell out of favor with white land owners. Instead, colonists fed the abundant and easily-captured animals to servants, slaves, and livestock – a practice, which led to controversy according to local lore.[3] Numerous sources mention a story in which “tidewater slaves” from the Chesapeake region staged a protest against their terrapin heavy diet and prompted the State of Maryland to mandate that slaves be fed terrapin no more than three times a week.[4] However, no record of the supposed rebellion or the subsequent legislation exists in official state records.[5]

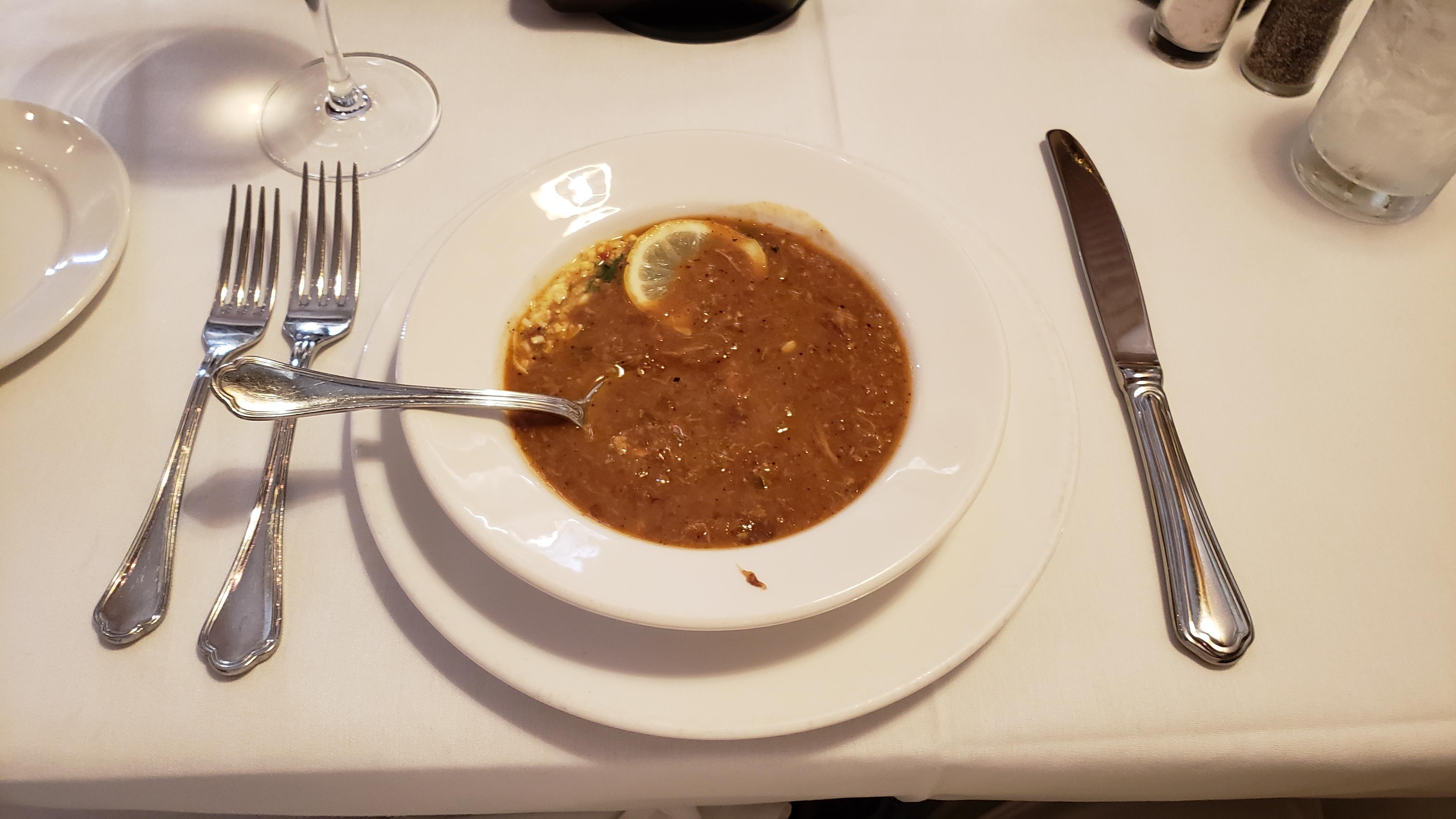

By the 1800s tastes had changed and demand for the turtle was growing. Terrapin was a mainstay on tables throughout Washington and the Chesapeake region. President Andrew Jackson was known to have had pre-prepared turtle soup shipped to the White House and it was common to see D.C. restaurants trying to tempt new customers by advertising their terrapin dishes.[6] An article from The Evening Star gives an idea of what these turtle-loving Washingtonians were after:

“The flesh is white and sweet, and the entire animal can be used with the exception of the shell, the claws, and the gall bladder. The variety of ways in which the flesh of the terrapin can be served is known to all lovers of good living. The soup is the most common, but a steak is said to be prime eating. At any rate the caterer always has a good word to say for the terrapin, and he is sorry when the season is over.”[7]

The humble terrapin gradually entered the nation’s fine dining scene. New York City’s Delmonico’s, considered by many to be the best restaurant in the country, was serving turtle soup to its discerning clientele by at least the mid-1800s. In 1851, Mississippi’s Senator Foote and Louisiana’s Senator Downs attended a dinner party at Delmonico’s at which they slurped down turtle soup and delivered speeches in favor of the 1850 Compromise.[8] Once a staple for slaves, terrapin was now feeding those who controlled the future of the slave-trade.

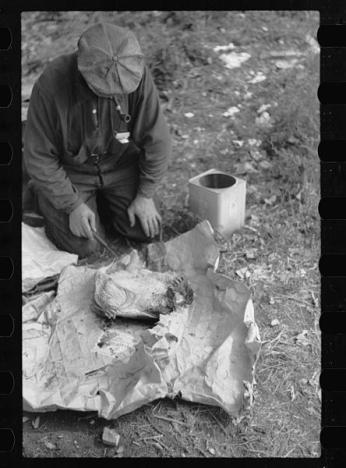

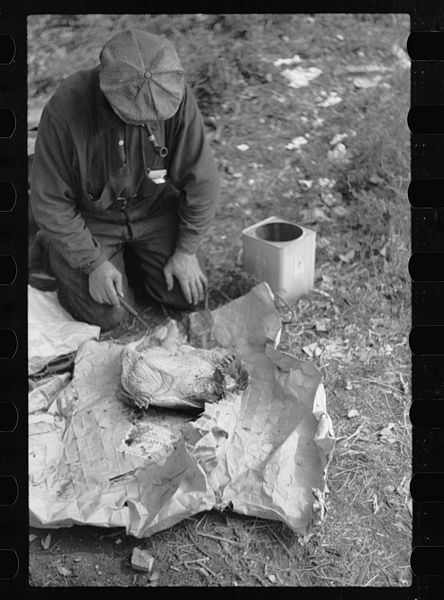

Demand for terrapin continued to grow and reached its height around the turn of the century. The nation’s gourmands believed that any restaurant worth its salt ought to serve turtle soup and they expected the best to use Chesapeake turtles. The Chesapeake region’s “tarpinners,” as those who caught and sold terrapin were known, worked hard to satisfy the now national appetite. Although terrapins were still relatively plentiful, Market prices for the Chesapeake diamondback tripled from 1881 to 1882.[9]

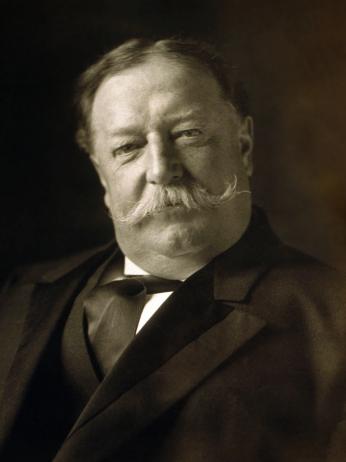

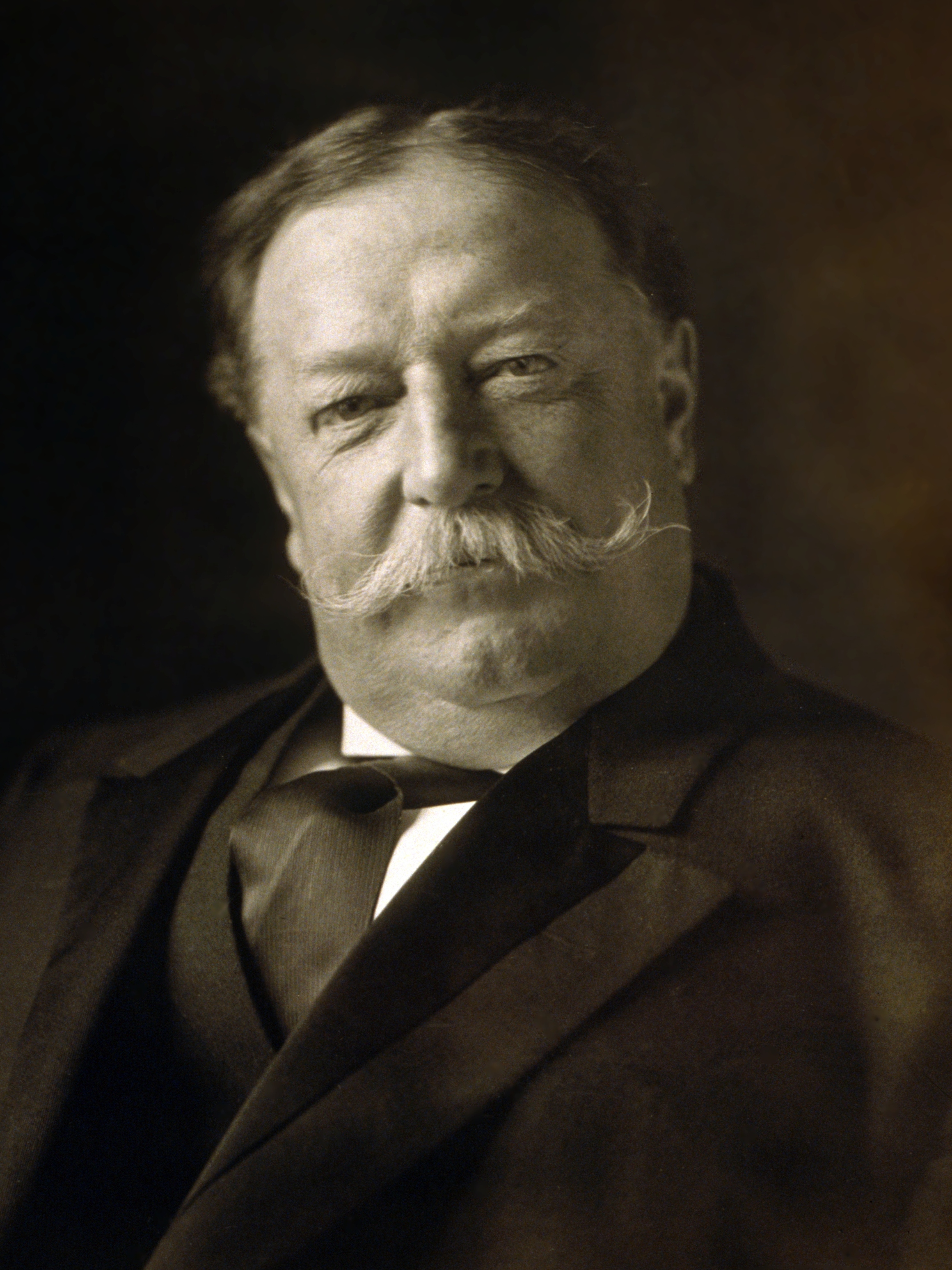

America’s obsession with turtle soup continued well into the 1900s despite dwindling terrapin numbers and steepening prices. President William Taft loved terrapin soup so much that a version of the dish was named in his honor. “Taft Terrapin Soup” was prepared by a specially commissioned chef, who, in addition to the meat of one large turtle, used 4 pounds of veal in the broth and was sure to serve the President his soup with glass of champagne.[10]

The popularity of terrapin led to overharvesting and a shrinking supply of turtles, which became a matter of national importance. Some Chesapeake tarpinners took it upon themselves to establish terrapin farms and, in 1902, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries followed suit, successfully petitioning Congress to fund a multimillion dollar terrapin test farm in North Carolina. Around the same time, herpetologist Clifford M. Pope was attempting to crossbreed Texas and Chesapeake diamondbacks to improve the flavor of the Texan turtle and undermine the Chesapeake diamondback’s status as the best tasting turtle.[11]

Efforts to bolster the nation’s quality turtle supply ultimately failed, but an impending shift in national eating habits would have undermined these endeavors regardless of their success. Mechanized farming was starting to take off and, when compared with chicken, beef, and pork, terrapin was far too difficult to efficiently rear and butcher. Mechanized farming saw the American palate narrow. The terrapin, and other peculiar foodstuffs, experienced a rapid decline in popularity.[12] While turtle-free “Mock Turtle Soup” had a slightly longer shelf life, it has also since fallen out of favor.

Though some restaurants, such as Acadiana on New York Ave., still include turtle soup on their menus, the death of the turtle trend, coupled with state and federal restrictions on terrapin harvesting, make it unlikely that we’ll see a major rebound in popularity anytime soon. Maryland Crabs remain a draw for hoards for diners but terrapin soup appears to be a thing of the past.

Footnotes

- ^ “Maryland State Reptile – Terrapin Turtle.” Maryland Manual On-Line. Last modified July 27, 2017. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/01glance/symbols/html/reptile.html. “School Mascot.” Maryland Athletics. Last modified April 29, 2015. http://www.umterps.com/ViewArticle.dbml?ATCLID=210056927.

- ^ Brennessel, Barbara. Diamonds in the Marsh: A Natural History of the Diamondback Terrapin. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New Hampshire, 2006. 137-138.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.; Cook, Bob. “A Natural History of the Diamondback Terrapin.” Underwater Naturalist 18, no. 1 (1980): 250-30.; Roosenburg, Willem. “The History of Commercial Exploitation of the Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin): Lessons for Turtle Conservation.” PowerPoint. Ohio University, Athens, OH, Date Unknown.; “Save the Terrapins.” The Baltimore Sun, Aug. 17, 2016.

- ^ Terrapin was known to be fed to slaves but although the story of the slave rebellion and subsequent legislation appears in a number of sources, there is little evidence supporting its validity. Additionally, it is also important to note that the terrapin story bears a striking resemblance to stories concerning the consumption of New England Lobsters, which suggests the terrapin story may be an adaptation. (See: Tarantola, Andrew. Lobsters were once only fed to poor people and prisoners. Gizmodo, Aug. 13, 2014. https://gizmodo.com/lobsters-were-once-only-fed-to-poor-people-and-pris….)

- ^ Jackson, Andrew, and Marshall Parks. “Marshall Parks to Andrew Jackson, August 31, 1829.” 1829. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/maj011720/. “McGrath’s Washington Coffee-House.” The Whig Standard (Washington), Nov. 1, 1844. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.; “Old Point Hotel.” The Daily Union (Washington), May 31, 1845. Library of Congress, Chronicling America.; “Oyster for the Million.” The Daily Union (Washington), Oct. 5, 1846. Library of Congress: Chronicling America. “The Empire.” The Republic (Washington), Jan. 4, 1951. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ “The Terrapin and its Habits.” The Evening Star (Washington), Jun. 17 1882. Library of Congress: Chronicling America

- ^ “True to its Instincts.” The Daily Union (Washington), Jan. 22, 1851. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ “The Terrapin and it’s Habits.”

- ^ Brennessel, Diamonds in the Marsh, 142.

- ^ Ibid., 143-144.

- ^ Hitt, Jack. “What Ever Happened to Turtle Soup.” Saveur. Oct. 14, 2015. https://www.saveur.com/history-of-turtle-soup-hunting.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)