Cleveland Park’s Very Own Vineyard

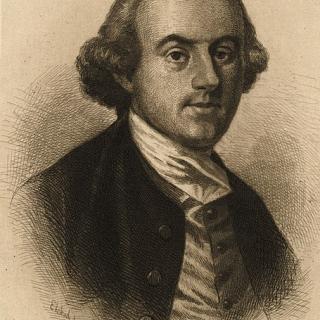

Local wine sales have reached record heights in recent years. But even though Virginia and Maryland’s 350+ wineries are beginning to enjoy the fermented fruits of their labor, the west coast remains the hub of wine production in the United States.[1] Over 92% of the country’s wine is produced on the west coast and Napa Valley remains the recognized capital of American wine.[2] However, the area's amateur sommeliers can take pride in the fact that John Adlum, “father of American viticulture,” called D.C. home.[3]

John Adlum was born in York, Pennsylvania in 1759 and joined the Revolutionary Army at the age of seventeen. After being captured by the British, Adlum returned home and became a land surveyor and speculator. His work introduced him to the east coast’s many wild grape varieties and left him with the fortune he would later use to develop his vineyard.[4]

In 1798, Adlum retired from land surveying and speculation, bought an estate in Havre de Grace, Maryland, and began cultivating grapes and making wine full time.[5] Like those before him, Adlum tried to recreate foreign wines by transplanting European vines but after disease and pests wreaked havoc on his crops, he made it his mission to use only native grape varieties.[6]

Before long, Adlum received presidential recognition for his work. On October 7, 1809, Thomas Jefferson wrote Adlum a letter. Jefferson said that while in office, a Maryland Congressman had given him a few bottles of Adlum’s Alexander-grape wine. Jefferson wrote:

This was a very fine wine, and so exactly resembling the red Burgundy of Chamberlin, (one of the best crops) that on a fair comparison with that, of which I had very good on the same table, imported by myself from the place where made; the company could not distinguish the one from the other.[7]

Adlum believed that it was his patriotic duty to document, preserve, and make use of native grapes and the president agreed. Jefferson closed his letter writing that the country ought “to push the culture of [the Alexander] grape, without losing our time and efforts in search of foreign vines, which it will take centuries to adapt to our soil and climate.”

In 1814, Adlum moved from Maryland to Washington D.C. and petitioned the government to lease him public land so he could start an experimental Vineyard.[8] In his memoir, Adlum wrote that he planned to:

“procure cuttings from different species of the native Vine, to be found in the United States, to ascertain their growth, soil, and produce, and to exhibit to the Nation a new source of wealth, which had been too long neglected.”[9]

Adlum’s application was denied and so, he was “obliged to prosecute the undertaking [himself].”

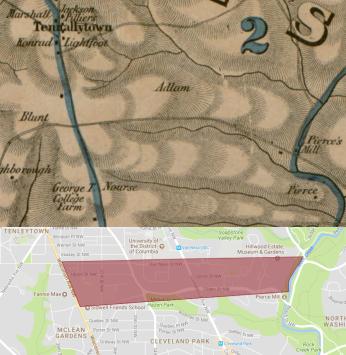

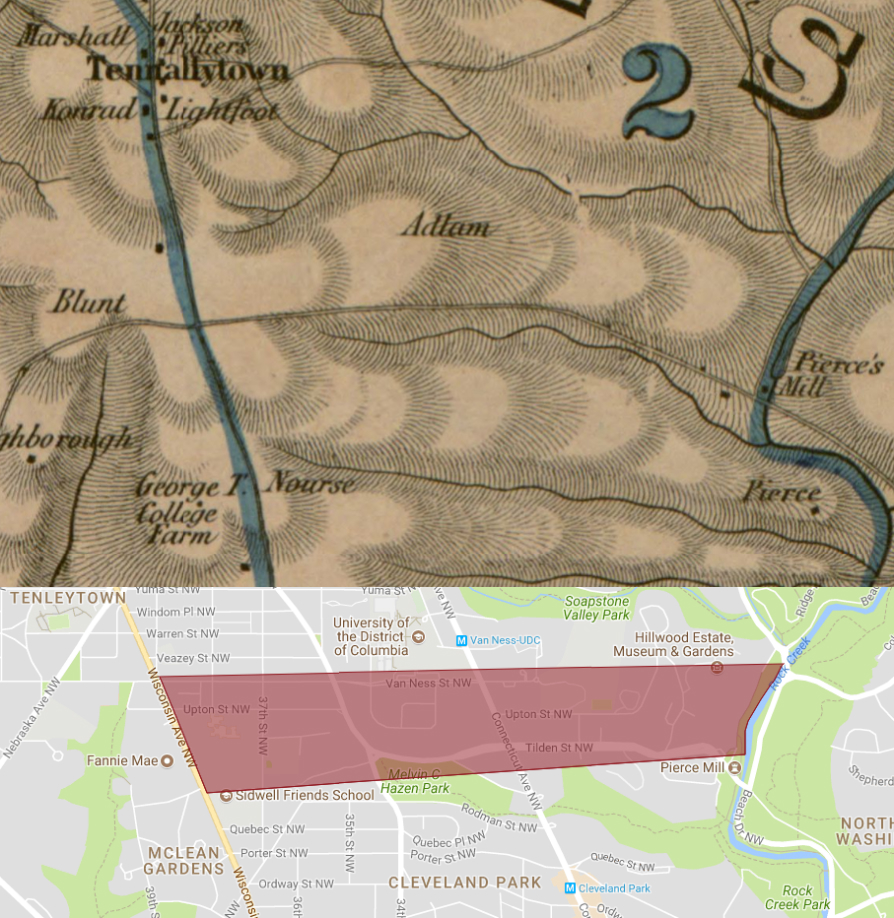

In 1814, Adlum bought 200 acres of land in what is now Cleveland Park, Van Ness, and Forrest Hills. He appropriately named the estate “The Vineyard” and planted a variety of vines.

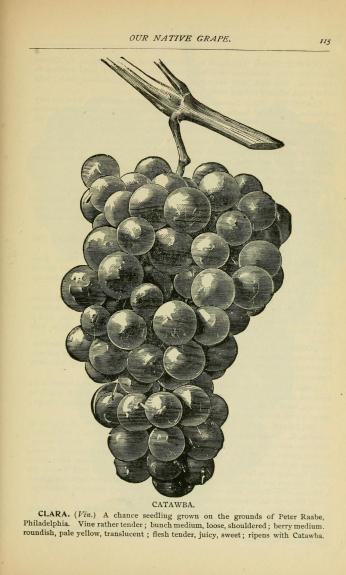

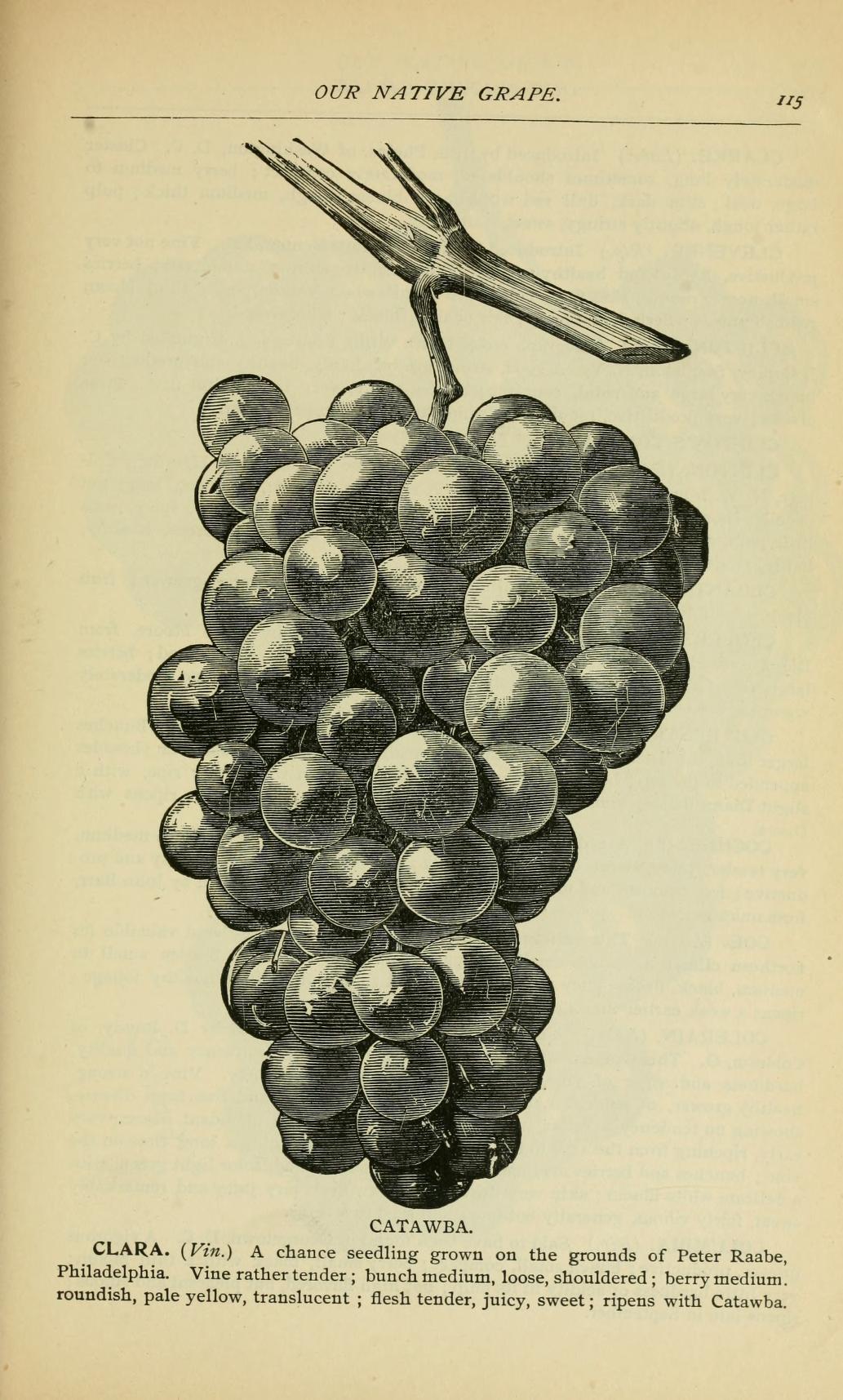

Having previously focused on the Alexander grape, Adlum switched his attention to the Catawba. In April 1822, Adlum sent one of his first bottles of Catawba wine to his old pen-pal Thomas Jefferson. On April 20, Jefferson wrote back affirming that the new grape made for a “truly a fine wine, of high flavor.”[10] With this show of approval, Adlum placed his first ad in the American Farmer on June 28.

In addition to simply reprinting Jefferson’s complimentary letters, Adlum placed ads encouraging Fourth of July parties to show their patriotism by celebrating with American wine.[11] In 1823, he published his book: Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America, and the Best Mode of Making Wine. The book was the first of its kind in the United States and helped establish the Catawba as the foremost grape in American winemaking.

Adlum remained the most famous figure in America’s emergent winemaking community throughout the 1820s. He published a number of writings on American vines and wines and received correspondence from winemakers near and far. However, Adlum’s fame didn’t last. By 1830, more successful winemakers had arrived on the scene and the community left Adlum behind.[12] He passed away March 14, 1836 and was buried in Georgetown’s Oak Hill Cemetery.[13] His vineyard was gradually carved up after his death.

In extolling the virtues of the Catawba, Adlum undoubtedly contributed to the advancement of American winemaking. But, Professor Thomas Pinney argues that Adlum was a relatively poor winemaker.[14] In his memoir, Adlum acknowledges that, while European winemakers ferment their wine at about 70 degrees, he believed fermenting at 115 degrees provided better results and he suggested “adding a few pounds of sugar” to each batch of wine.[15]

To be fair to Adlum, Americans’ tastes likely differed from those of today. America-bound European wines were often preserved with the addition of sugar or brandy and these wines were exposed to warm topical temperatures en route. Sweeter wines, such as Madeira and Port, were among the most commonly imported wines during Adlum’s time.[16] Adlum’s contemporaries may have found his wine more palatable than drinkers today, but while Thomas Jefferson seemed to enjoy the free samples, there are a number of other less favorable accounts of Adlum’s wine.[17]

It may be because of his peculiar methods that Adlum’s wine never earned him much money. He spent his retirement eating through his fortune and died a relatively poor man.[18] However, this line from the title page of his 1823 book suggests he wasn’t in it for the payday:

“What is life to a man that is without wine? for it was made to make men glad. Moderately drank, and in season, bringeth gladness of the heart, and cheerfulness of the mind.”[19]

The quote makes a perfect toast for anyone wishing to honor Adlum. So, let’s raise a glass to the father of American viticulture and be thankful it’s not full of Adlum’s own vintage!

Footnotes

- ^ Abha Bhattarai, “As wine sales hit record highs, Virginia wineries are in a race for grapes,” Washington Post, Sept. 23, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/capitalbusiness/as-wine-sales-hit-record-highs-virginia-wineries-race-to-keep-up/2016/09/23/acbaadb6-750e-11e6-be4f-3f42f2e5a49e_story.html?utm_term=.2115400ff7bf.; Going Out Guide, “You know about Virginia wineries. These Maryland ones are worth visiting, too,” Washington Post, Oct. 27, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/going-out-guide/wp/2016/10/27/you-know-about-virginia-wineries-these-maryland-ones-are-worth-visiting-too/?utm_term=.e35ae21a65ba.

- ^ Northwest Farm Credit Services, “2017 Industry Perspective Wine/Vineyard” Industry Insights, https://www.northwestfcs.com/-/media/Files/Industry-Insights/Industry-P….

- ^ Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition (Berkley: University of California, 1989), 139.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John Adlum, Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America, and the Best Mode of Making Wine 2nd ed. (Washington: William Geer, 1828), 11. Penny, A History of Wine in America, 139.

- ^ Adlum, Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America, 11.

- ^ Ibid., 149.

- ^ Pinney, A History of Wine in America, 141.

- ^ Adlum, Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America, 3-4.

- ^ Ibid., 150.

- ^ John Adlum, “Fourth of July Parties,” American Farmer (Baltimore, MD), Jun 28, 1822. Internet Archive https://archive.org/stream/americanfarmer2223balt#page/112/mode/2up.; John Adlum, “Cultivation of Grapes and Fabrication of Wine,” American Farmer (Baltimore, MD), Nov. 29, 1822. Internet Archive https://archive.org/stream/americanfarmer2223balt#page/342/mode/2up.

- ^ Pinney, A History of Wine in America, 148-149.

- ^ “Maj John Adlum,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37190253/john-adlum

- ^ Pinney, A History of Wine in America, 141.

- ^ Adlum, Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America, 37.

- ^ Jackson Rohrbaugh, “What is Madeira? The Island Wine,” Wine Folly, Mar. 25, 2017, http://winefolly.com/review/what-is-madeira-wine/.

- ^ Pinney, A History of Wine in America, 145.

- ^ Ibid., 148.

- ^ Adlum, Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America, Title Page.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)