The Temperance Fountain Just Might Be the Ugliest Statue in Washington

In a city full of monuments and memorials like Washington, not all of them can be beautiful.

Exhibit A: The Temperance Fountain at Seventh Street and Indiana Avenue NW.1 It’s been called D.C.’s ‘ugliest statue’2 but it’s really more of an out-of-commission 19th century water fountain, which originally came with an ice tank, a bronze drinking cup and a basin for horses.3

Former Washington Post columnist John Kelly did his best to describe it in 2022:

“Though it doesn’t quench thirsts today, intertwined bronze stylized dolphins once spewed water from their mouths under a four-sided stone canopy, each side of which was chiseled with a different worthy quality: FAITH, HOPE, CHARITY, TEMPERANCE. The granite canopy is surmounted by a bronze heron, a bird that spends much of its life in the water.”4

So, to whom do we owe the honor of hosting this… unique piece of public art?

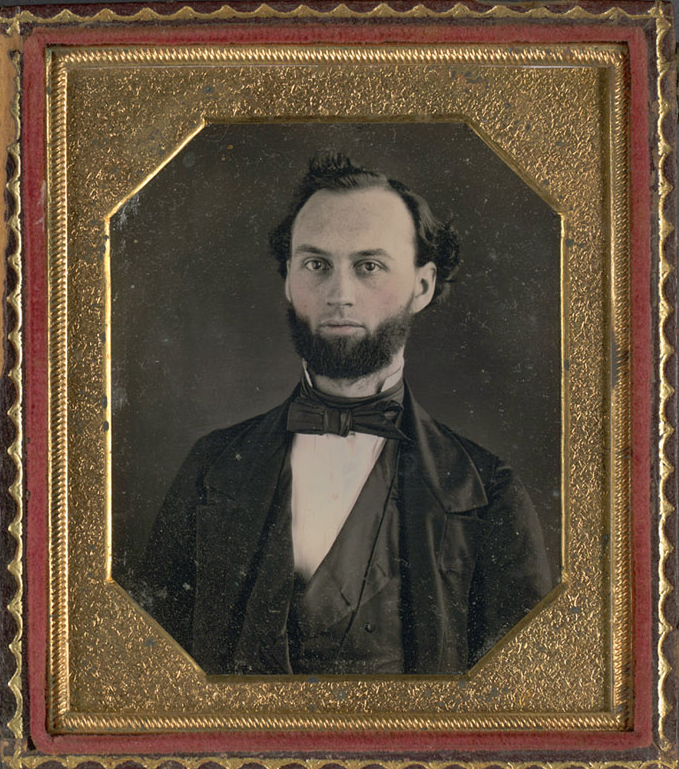

Well, that would be Henry D. Cogswell, a millionaire dentist from San Francisco with a passion for the Temperance Movement. An avid philanthropist and prohibitionist, his goal was to provide ice-cold drinking water to cities across the country in an attempt to curb people’s thirst for alcohol.5 Cogswell blamed alcohol for the country’s problems and figured that if people had refreshing water readily available, they might stray from saloons and pubs.6 When he originally began erecting fountains throughout San Francisco, Cogswell pledged to provide one fountain for every 100 saloons.7 He never achieved that goal but during the last decades of the 19th century, he did manage to send fountains (sources estimate between 20 and 40) to cities across the country. Here in D.C., we received ours in 1884.8

Cogswell designed and paid for each statue out of pocket. Some statues incorporated animals — D.C.’s and New York’s have likenesses of herons and “grotesque fish” — while others portray human figures like Benjamin Franklin or (often) Cogswell himself.9 Temperance fountains weren’t a totally unfounded idea, and other organizations such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union picked up the same strategy.10

But before too long, cities who originally accepted Cogswell’s statues began to abandon them and many declined them altogether.

Cogswell’s fountains often faced criticism because people saw them as self-advertising. With no children, it seemed Cogswell was openly trying to strengthen his legacy through philanthropy. He used the temperance fountains to place his likeness in city-centers throughout the United States. (Indeed, Cogswell originally wanted to gift D.C. a fountain with his likeness, but the design was rejected and replaced by the bronze heron that now stands at the top of the statue’s canopy.) Senator Sheridan Downey, a huge critic of Cogswell and his pet project, told The Evening Star in 1945, “He was a wealthy eccentric who believed he could perpetuate his name through the centuries by giving away monuments — usually of himself — to any city that would accept one.”11

Others wanted the fountains gone because of their message. Temperance divided the nation, and its opponents felt that the fountains were “hectoring” or useless.12 But many of Cogwell’s designs faced criticism simply because, well, people just thought they were ugly. To that point, Senator Downey called D.C.’s fountain a “monstrosity of art.”13

For these reasons, people tore down or desecrated Cogswell’s fountains all over the country, including In 1894, a mob tore down one of his fountains inhis hometown of San Francisco.14 In Rockville, Connecticut, townspeople took the extra step of throwing their Cogswell fountain into nearby Snipsic Lake.15

The reaction in D.C. was less severe though mere months after the statue’s D.C. placement in 1884, the city stopped maintaining its ice-bucket, and later disconnected its water.16 For the better half of the 20th century, a fountain meant to fight against alcohol sat idly in front of Apex Liquor Store on Seventh Street and Pennsylvania Avenue until it was moved about 100 feet to Indiana Avenue NW.17

Today only a handful of Cogswell statues remain. So, when it was all said and done, Cogswell succeeded in his goal of building a legacy for himself, but perhaps not in the way he hoped. Prohibition passed in 1919, 19 years after his death, banning alcohol across the country. But, like most of Cogswell’s fountains, Prohibition was unpopular and had a short lifespan — it was officially overturned in 1933.

We can say one thing for Henry Cogswell, however. In the 1970s, his philanthropy inspired the creation of the Cogswell Society, a group of 12 men “devoted to drinking, good food, and joke-telling” who meet on the first Friday of every month “to discuss ‘the study of man’s excesses and the lack of temperance in past and present cultures.”18 Their slogan is “Temperance….I’ll drink to that!”19 Now, the Cogswell Society is also dedicated to protecting D.C.’s ugliest statue, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.20

Footnotes

- 1

- 2

- 3

John Kelly, “In 1884, a cantankerous millionaire gave D.C. a fancy water fountain,” The Washington Post. August 27, 2022.; “The Temperance Fountain,” DC Design Tours.

- 4

- 5

“Temperance Fountain,” DC Historic Sites, accessed April 10, 2025.

- 6

Thomas Crosby, “A Bit of April Foolishness, and Fun,” The Evening Star, April 2, 1977. 21.

- 7

Gloria Lenhart, “Henry Cogswell and His Monuments,” FoundSF, Summer 2013.

- 8

Gloria Lenhart, “Henry Cogswell and His Monuments,” FoundSF, Summer 2013.

- 9

- 10

- 11

“Temperance Drinking Fountain Removal Asked by Senator,” The Evening Star, April 12, 1945. 23.

- 12

- 13

“Temperance Drinking Fountain Removal Asked by Senator,” The Evening Star, April 12, 1945. 23.

- 14

“Image Breaker’s: Dr. Cogswell’s Statue Overturned,” The Morning Call, January 3, 1894. 8.

- 15

Jessica Ciparelli, “Cogswell Statue Dedication,” ReminderNews, October 22, 2005.

- 16

- 17

“…Toasted Temperance,” The Washington Post, September 21, 2003. C02.

- 18

Thomas Crosby, “A Bit of April Foolishness, and Fun,” The Evening Star, April 2, 1977. 21.; “The Temperance Fountain,” DC Design Tours.

- 19

Greg Kitsock, “All’s Well That Ends With a Drink to Cogswell,” Washington City Paper, March 6, 1992.; Thomas Crosby, “A Bit of April Foolishness, and Fun,” The Evening Star, April 2, 1977. 21.

- 20

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)