Ebola Comes to Reston

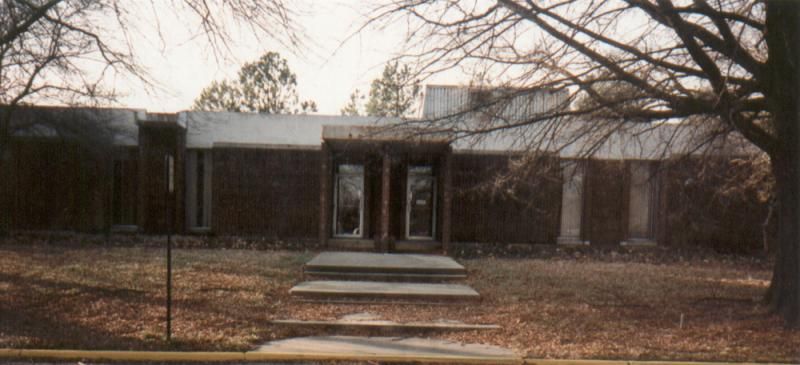

Looking at old photos of Isaac Newton Square in Reston, Virginia you would never guess that a silent killer once lurked here.[1] But in the fall of 1989 that’s exactly what happened.

Back then, the square was home to The Reston Primate Quarantine Unit, a facility in charge of looking after newly-imported monkeys during the government-mandated 31-day quarantine period. Nicknamed the “monkey house,” the unit was owned by Hazelton Research Products and handled thousands of monkeys each year, which were brought to the U.S. for scientific, educational and exhibition purposes.[2][3]

On October 4, 1989, the Quarantine Unit received a shipment of 100 monkeys from a Philippine facility.[4] By November, nearly one-third of the animals had died – a much higher percentage than normal – of mysterious causes.[5] Dan Dalgard, the consulting veterinarian of the unit, was alarmed and contacted the US Army Medical Research Institute (USAMRIID). Located at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland, the USAMRIID focuses on the development of medical solutions to diseases in hopes of protecting soldiers.[6] Dalgard talked to Peter Jahrling, a virologist at USAMRIID, who told him to send a few samples of the dead monkeys.

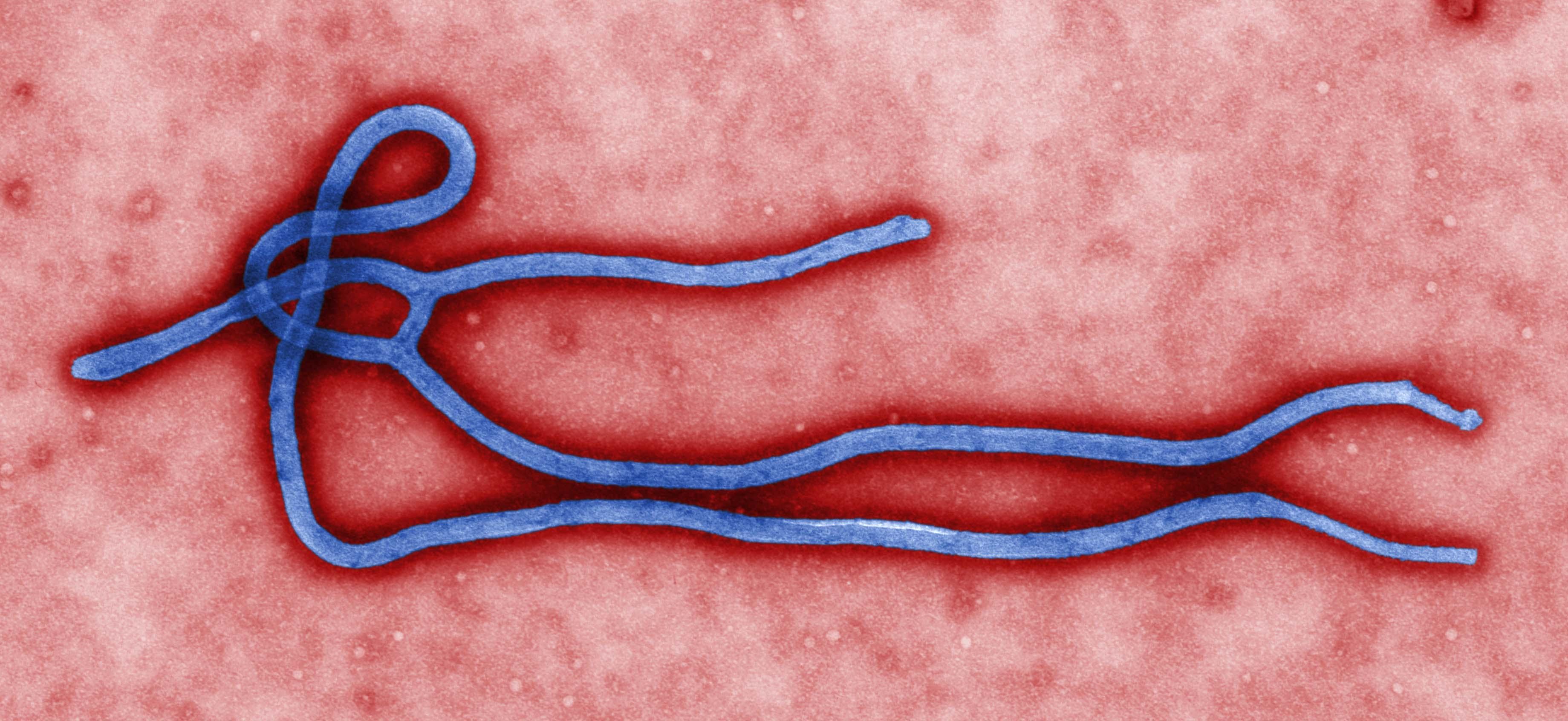

Fourteen days later, officials realized what they were dealing with. An intern at USAMRIID, Thomas Geisbert, analyzed the samples from Reston and found a filovirus-thread virus. The next day, Jahrling tested the samples twice and they tested positive for Zaire ebolavirus, the most dangerous Ebola strand.

"We have a national emergency in our hands," General Philip K. Russell, the Major General of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command, told colleagues. "This is an infectious threat of major consequences."[7]

Officials at Fort Detrick contacted the Center for Disease Control. They had a lot of questions to consider. What were they going to do with the monkeys? How would they handle any people that got sick? What if the Ebola strand was not Zaire ebolavirus but something worse? Would the army and the Center for Disease Control work together or would the CDC take over the case?

"I can still remember that day," Frederick Murphy, then the director of the National Center for Infectious Diseases at the CDC, told FOX News in 2014.[8] "Everyone at the table was very concerned that this was going to be a very dangerous episode."

While officials were fearing the worst, the public was largely oblivious. Back in 1989, Ebola was not nearly as well known as it is today.

"The big difference between now and 1989 is that nobody else knew what Ebola was," remembered Colonel Gerald Jaax, the leader of the Army unit handling the outbreak.[9]

In the end, it was decided that the army would handle the monkeys and the monkey house, and the CDC would look after any sick humans.

From December 4–7, soldiers were sent to the monkey house in Reston to euthanize the 450 monkeys that were left in the building and get samples to take back to USAMRIID.

To avoid arousing suspicion, the soldiers wore civilian clothes when they arrived, so that neighbors would not suspect anything out of the ordinary. Once out of sight, they would change into protective suits.

The process was not without incidents. On the first day, Jaax and his soldiers ran into a group of monkey handlers and Dalgard with no protective gear. On the second day, a monkey in Room C escaped.

In an interview for a veterinary medical journal in 2005, Jaax said:

"Several of us spent the better part of a day trying to catch it. When we talk about the Reston incident, we compare the frustration of that day with the Hollywood version in the movie 'Outbreak,' in which an infected monkey was coaxed from a tree and captured within minutes. It is a great example of reality vs. Hollywood."[10]

After all the monkeys were disposed of, the building underwent days of decontamination that ended on December 18.

Two of the four handlers in the monkey house came down with signs of disease. The first was the man who had the heart attack. The second was a worker who threw up on the front lawn of the building and had a fever of 101. He was put in isolation in Fairfax Hospital. At the time, these workers tested negative for Ebola.

Months later, on April 6, 1990, the four workers were tested again, and their blood showed that they had antibodies against Ebola proving that they had been infected during an outbreak, but the virus had not made them sick.[11]

How had they – and the entire community – avoided the worst? As it turned out, the infection in the monkey house had been misidentified. It was most certainly Ebola, but it was not the deadly Zaire ebolavirus strain that officials had feared. Rather, it was a previously unknown strain, which closely resembles Zaire ebolavirus, but is not harmful humans. Officials named this new strain Reston ebolavirus.[12]

"It turned out, unbelievably at the time, that the strain of the virus that killed the monkeys was almost as virulent as the African Strain – even though the caretakers were not infected," Murphy explained in 2014.[13]

It wasn’t until several years after the incident that the public began to grasp the severity of what might have been. In 1994, Richard Preston published his best-selling book, The Hot Zone, which explored the Reston outbreak in detail. Reviewing the book for The Washington Post, Malcolm Gladwell hit on the salient point:

"The only known strain not lethal to man, fortunately, is the strain found in Reston, which by some genetic fluke kills monkeys but not human beings. But that is not what the Army and the Centers for Disease Control thought when they first examined blood samples from the monkey house. They thought that the Hazelton monkeys – with whom numerous lab workers had had repeated and close contact before going home to wives and children and bars and restaurants all over the Washington area – were infected with the deadly and highly infectious Ebola Zaire. Preston's description of the long days and hours during which the Army and the Centers for Disease Control were still under the misapprehension will make your blood curdle."[14]

Indeed, the containment operation went on with less public attention than one might expect, considering what we now know about Ebola. According to Preston, officials gave statements that "were designed to create an impression that the situation was under control, safe, and not at all that interesting."[15] But based on the mistakes that had been made – from workers continuing to work in the monkey house with little protection to the 14 days it took to identify the disease – the outbreak could have been devastating if the strain had been Zaire ebolavirus as originally feared.

Reflecting on those tense days later, Peter Jahrling remarked, "My concern is that people are saying, 'Whew, we dodge a bullet.' And the next time they see Ebola in a microscope, they'll say, 'Aw, it's just Reston,' and they'll take it outside a containment facility. And we'll get whacked in the forehead when the stuff turns out not to be Reston but its big sister."[16]

Fortunately, that worst case scenario hasn’t happened yet, though Reston ebolavirus was seen again in Philadelphia, Texas and Reston in 1990, Italy in 1992, and again in Texas in 1996.[17] In January 1997, Ferlite Scientific Research Farm, the farm in the Philippines which supplied the monkeys to Hazleton Research Products was permanently closed.[18]

In June 1995, Hazelton’s Reston Primate Quarantine Unit building where the original outbreak took place was demolished.[19] “I don't know any broker that wanted to step foot in the place," real estate broker John McEvilly told the Washington Post at the time. A new building went up, which now houses a Kindercare.

See more of Jan Bradshaw's photos of the Reston Monkey House →

Footnotes

- ^ Haggerty, Maryann. “Years After Scare, Reston 'Monkey Building' Coming Down." The Washington Post January 17, 1995. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1995/01/17/years-after-scare-reston-monkey-building-coming-down/34191093-f9be-4f57-8e09-2435eb84851a/?utm_term=.906dd225822d

- ^ Haggerty, Maryann. “Years After Scare, Reston 'Monkey Building' Coming Down." The Washington Post January 17, 1995. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1995/01/17/years-after-scare-reston-monkey-building-coming-down/34191093-f9be-4f57-8e09-2435eb84851a/?utm_term=.906dd225822d

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. "42 CFR 71.53 - Nonhuman primates." October 1, 2007. sec. Definitions, Uses for which nonhuman primates may be imported and distributed. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2003-title42-vol1/xml/CFR-2003-title42-vol1-sec71-53.xml

- ^ Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. New York: Random House, Inc., 1994. pp. 111

- ^ Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. New York: Random House, Inc., 1994. pp. 115

- ^ Wheeler, Gary A. USAMRIID: Biodefense Solutions to Protect our Nation. December 4, 2016. http://www.usamriid.army.mil/index.htm

- ^ Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. New York: Random House, Inc., 1994. pp.155

- ^ Vlahos, Kelley Beaucar. "How a Virginia suburb became an Ebola epicenter." Fox News September 19, 2014. http://www.foxnews.com/science/2014/09/19/how-virginia-suburb-became-ebola-epicenter.html

- ^ Barakat, Matthew. "25 years ago, a different Ebola outbreak - in USA." USA Today August 10, 2014. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/08/10/ebola-1989-outbreak/13860929/

- ^ dvm360.com staff . "An Interview with... Drs. Jerry and Nancy Jaax." dvm360 March 1, 2005. http://veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/interview-with-drs-jerry-and-nancy-jaax

- ^ Cohn, D'Vera. "4 Handlers in VA. Get Ebola Virus." The Washington Post April 6, 1990. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1990/04/06/4-handlers-in-va-get-ebola-virus/01e45589-99da-4264-956d-84c20f297244/?utm_term=.3c49823e0523

- ^ The Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease). December 27, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/about.html

- ^ Vlahos, Kelley Beaucar. "How a Virginia suburb became an Ebola epicenter." Fox News September 19, 2014. http://www.foxnews.com/science/2014/09/19/how-virginia-suburb-became-ebola-epicenter.html

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm. “Killer Monkeys Of Reston.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C. October 16, 1994, sec. Book World.

- ^ Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. New York: Random House, Inc., 1994. pp. 203

- ^ Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. New York: Random House, Inc., 1994. pp. 257

- ^ Brown, David. "Exporter's Monkeys Tested for Ebola Virus." The Washington Post April 20, 1996. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1996/04/20/exporters-monkeys-tested-for-ebola-virus/0094d353-ce05-46cf-8816-5bd6e6db7047/?utm_term=.80aaddabeb13

- ^ Berry-Cabán, Cristóbal S. "Reston’s Hot Zone ─ 20 Years Later." The Internet Journal of Preventive Medicine (2010). sec. Conclusion http://ispub.com/IJPRM/2/1/12768

- ^ Haggerty, Maryann. “Years After Scare, Reston 'Monkey Building' Coming Down." The Washington Post January 17, 1995. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1995/01/17/years-after-scare-reston-monkey-building-coming-down/34191093-f9be-4f57-8e09-2435eb84851a/?utm_term=.906dd225822d

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)