Chuting Books to the Congressional Library

Until 1897, the Library of Congress, or Congressional Library as it was more commonly called, was located within the most convenient place for its Congressional patrons: the Capitol Building. A separate building for the Library was first proposed in 1871 by Librarian of Congress, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, who expressed concerns that the Library was gaining more volumes and quickly running out of space. By 1875, the Congressional Library had completely exhausted its shelf space, and “from sheer force of necessity began to pile its incoming books, maps, music, prints, photographs, and manuscripts on the floor.”[1] Construction on the new building finally began in 1889 and continued through February 1897. Although the 20 year wait for the physical structure was a long one, it seemed that the months between the building’s completion in February 1897 and its opening day on November 1, 1897 were the longest of all.

Throughout these nine months, librarians and engineers joined together to try and solve one major problem: how would they move all of the Library’s contents the quarter of a mile distance from the Capitol to the new library without “loss, damage, and confusion.”[2] This would be no easy task considering that “all of the Library’s contents” included 750,000 volumes of books, 250,000 pamphlets, 300,000 unbound periodicals, 200,000 pieces of music, at least 40,000 maps, and a vast amount of photographs and manuscripts.[3]

The librarians were especially keeping the Boston Public Library in mind while trying to come up with a solution. Just a few years prior, Boston had moved its 460,000 volumes into a new building—a project that occupied an entire year, plus months more of crippling confusion.[4] The Congressional Library would have to move over double what Boston had, and moreover, it would need to attempt to do so before Congress entered back into session at the beginning of December.

The transfer of books was supposed to begin in March of 1897, but an extra session of the 55th Congress forced a delay of the project.[5] In May, it was announced that the library move would begin immediately after Congress adjourned in July, and would take about 60 days to complete.[6]

On July 20, The Washington Post reported that the old library would likely be closed for three weeks while book removal took place, but on July 30, the newly appointed Librarian of Congress John Russell Young, announced that the Congressional Library in the Capitol would be closed indefinitely starting July 31, 1897.[7] The closure was met with surprise, but Librarian Young explained that the book transfer was an enormous task that they wished to finish without causing too much inconvenience to frequent library goers. The way to achieve this would be an uninterrupted transfer process beginning at a time in the summer when the library was always less populated, and hopefully ending when visitors increased again in the fall.[8]

The book transfer began on August 1, 1897 with an arduous book labeling process. The marking and carding of books and other material was the longest and most complicated phase of the entire operation because “various classes of books in the old library [were] widely scattered,” with some “on shelves, some in chaotic heaps, some classified, and much unclassified.”[9]

When labeling began, “all Library work was suspended in every department except what was necessary for the transfer of the books,” and every member of the Library staff was assigned to helping with this major task.[10] With all hands on deck, the labeling process moved along swiftly. In fact, on average, one worker was able to label about 2,000 volumes a day, which allowed this phase of the project to last several weeks, rather than several months.[11]

After those several weeks of labeling, the librarians were ready for phase two, which included chutes, wagons, and even an audience. Engineers constructed chutes made of pine wood that were 13 inches wide by 6 inches deep, and held in place by scantling and braces. “Two chutes extending from the upper gallery [in the Capitol] to the floor were constructed in each of the three old halls of the Library, and one down the east front steps of the rotunda.”[12]

Next, the pre-labeled books were packed into specially made boxes that fit one shelf’s worth of books and could slide down the “well-soaped” wooden chutes.[13]Superintendent of the Congressional Library Bernard Green explained the rest of the transfer procedure in his 1897 report to Congress:

“All transfer of the matter was made by means of wooden boxes, consisting of open trays and handbarrows. These were loaded and handled by workmen who generally carried them on the shoulder along the floors or upstairs, but the more heavily loaded boxes and all handbarrows, were carried by two men, one at each end. Where considerable descents occurred, as from the Library galleries or at the front steps of the Capitol, chutes were used, down which the loaded boxes were slid. Thence they were piled into wagons going between the Capitol and the Library building, carrying the loaded boxes and returning the empty ones. On arrival at the building, usually at the west or main entrance on the ground floor, under the porte-cochère, workmen again carried the boxes along that floor, either to the basement rooms, in which much of the unclassified matter was temporarily deposited and stacked, or to the elevators in the several book stacks…empty boxes were returned by the same route and method of handling to the Capitol to be reloaded, except that, where the chutes occurred, they were hoisted by hand with a single-whip tackle.” [14]

About 35 to 50 men carried out the physical moving portion of the transfer each day, with the addition of two to three “ordinary one horse express wagons,” which cost $2.50 per day to hire.[15]

Once the boxes were unloaded at the library, the “books were cleaned by a blast of air which raised clouds of dust even from volumes supposed to have been previously cleaned.”[16] When the books were dust-free, they were carried to predesignated locations, which were determined by four numbers penciled onto a colored 5-by-7 inch card attached to each box.[17] The numbered cards corresponded with a larger master plan of the new library.

“A plan showing every deck, and shelf, and division of the shelves, [had] been prepared, very much like the diagram of the seats in a theater. Each box of books [would] go to a certain seat, so to speak, and that seat [would] be crossed off as the box [was] sent out, properly marked. In this way no confusion [could] result.” [18]

When the location was determined from the plan and colored card, the box was “hoisted on the elevator to the proper floor or “deck,” as it [was] called, and the figures on the card direct[ed] just what row of shelves, what section of the row, and what shelf in the section, the books [should] be placed upon.”[19] Books were respectively shelved straight from the box, which had already been loaded in the correct order at the old library.

The entire book removal system was efficient, practical, and despite what it may seem, fast. The Evening Star explained the system further:

“The work of removing the books seems to the casual onlooker to be progressing slowly and laboriously. The spectacle of a handful of men carrying boxes of books across the rotunda of the Capitol, tobogganing them down a chute and transporting them a wagon-load at a time over the plaza to the new building, where another handful of men takes them in charge, seems at first glance to be a piecemeal method of handling the collection, when the vast number of books is taken into calculation. As a matter of fact, however, the work is not dragging along by any means, but is progressing with a great deal of rapidity. Although it is not shown on the surface, it means more than it appears on account of the system which is being followed. There is no duplication of labor, no waste of effort and every lick counts.” [20]

The transfer operation, though focused on efficiency, was quite the sight to see in the District, and provided Washingtonians plenty of entertainment in August 1897. According to The Washington Post, “hundreds of people congregate[d] at the east front of the Capitol daily to watch the books swiftly descend in the wooden troughs to wagons waiting below.”[21] With large crowds around, library staff took great care to prevent theft of the moving material by stationing watchmen in the Capitol rotunda, at the foot of the portico steps, in the hallways of both the new and old libraries, and especially in the moving wagons.[22]

Despite the hundreds of thousands of materials that were moved, not a single book or document was lost, stolen, or misplaced throughout the entire transfer process, which lasted from August through October.[23] With the books securely and carefully arranged in their new home, the Congressional Library was set to reopen on November 1, 1897, and thanks to the meticulousness and efficiency of the transfer method, every volume was available for use on opening day.

Footnotes

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.” 466.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1897. “Open Only This Week: Library of Congress Closed to Visitors To-Morrow,” July 30, 1897. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Evening Star. 1897. “Uncle Sam’s Books,” September 18, 1897. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A3….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1897. “Open Only This Week: Library of Congress Closed to Visitors To-Morrow,” July 30, 1897. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.” 466.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1897. “Sixty Days of Moving: Required to Transfer the Congressional Library,” May 25, 1897. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1897. “Open Only This Week: Library of Congress Closed to Visitors To-Morrow,” July 30, 1897. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.” 466.

- ^ Evening Star. 1897. “Opening the Library,” September 2, 1897. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A3….

- ^ Bernard R. Green. 1897. Report of the Superintendent of the Congressional Library Building.

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.” 466.

- ^ Bernard R. Green. 1897. Report of the Superintendent of the Congressional Library Building.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cole, John Y. 1972. “Library of Congress Information Bulletin.” 466.

- ^ Bernard R. Green. 1897. Report of the Superintendent of the Congressional Library Building.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1897. “Open Only This Week: Library of Congress Closed to Visitors To-Morrow,” July 30, 1897. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Evening Star. 1897. “Opening the Library,” September 2, 1897. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A3….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1897. “Watching the Book Chutes: Transfer of Volumes to the New Library Attracts Large Crowds,” August 20, 1897. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Bernard R. Green. 1897. Report of the Superintendent of the Congressional Library Building.

- ^ Ibid.

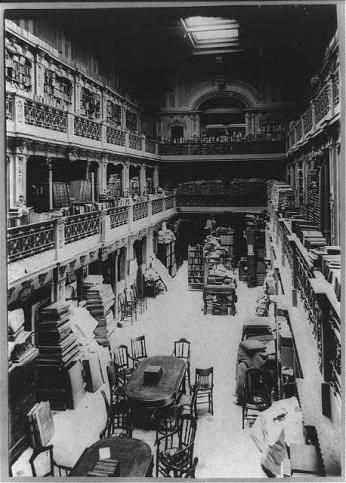

![“Washington D.C., Library of Congress 1897-1910.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Washington, D.C., Library of Congress. District of Columbia United States, Washington D.C, None. [Between 1897 and 1910] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/4a28645v.jpg?itok=DBSDxKZ_)

![“Washington D.C., Library of Congress 1897-1910.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Washington, D.C., Library of Congress. District of Columbia United States, Washington D.C, None. [Between 1897 and 1910] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/](/sites/default/files/4a28645v.jpg)

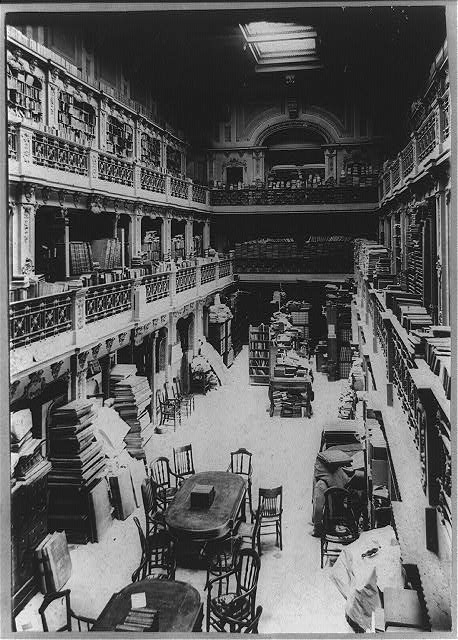

![“Library of Congress deposits in basement.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Library of Congress ... deposits in basement to. , None. [Between 1909 and 1920] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016821636/. “Library of Congress deposits in basement.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Library of Congress ... deposits in basement to. , None. [Between 1909 and 1920] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016821636/.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/20063v.jpg?itok=kTm6rNyR)

![“Library of Congress deposits in basement.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Library of Congress ... deposits in basement to. , None. [Between 1909 and 1920] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016821636/. “Library of Congress deposits in basement.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Library of Congress ... deposits in basement to. , None. [Between 1909 and 1920] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016821636/.](/sites/default/files/20063v.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)