Washington Confronts the AIDS Crisis

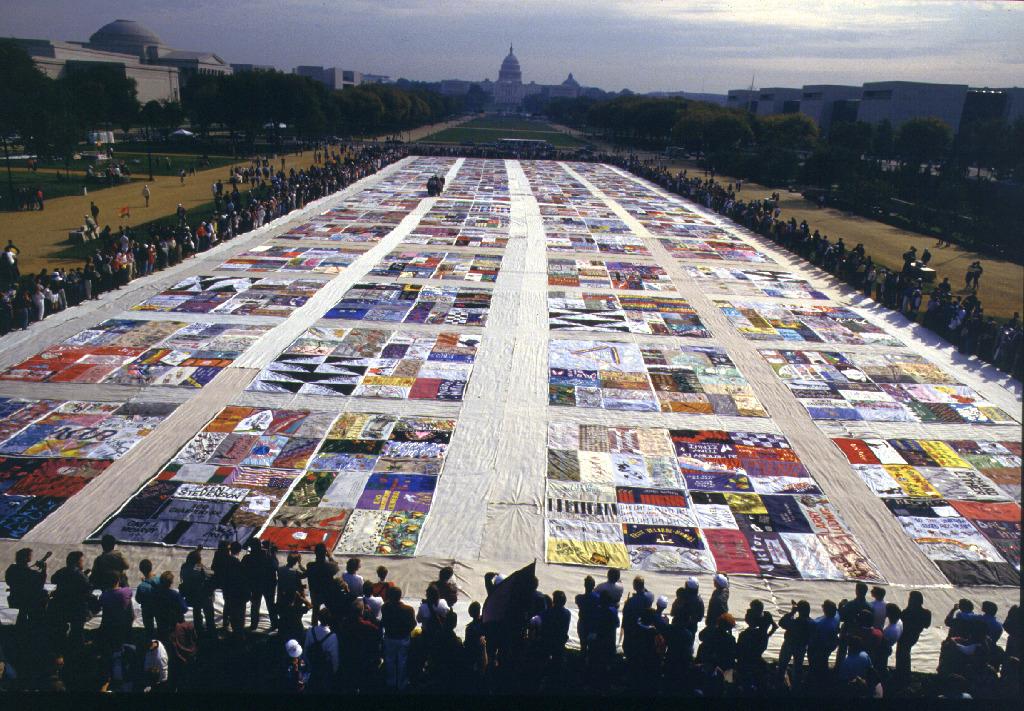

Although Washingtonians woke up to an elaborate quilt blanketing the National Mall on October 11, 1987, the atmosphere in our nation’s capital was far from warm and fuzzy.[1] Quite the opposite, the AIDS Memorial Quilt draped like a pall over two-blocks between the Washington Monument and the Capitol,[2] with 1,920 panels stitching together the memory of thousands of individuals who had already succumbed to the epidemic.[3] Each panel functioned like a headstone made of cloth, representing the deceased through dedications made by their friends and families.[4]

In a somber morning ceremony, relatives of victims and volunteers—including Whoopi Goldberg, Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, Robert Blake, and Harvey Fierstein—read the names of victims to a hushed crowd as the sun rose above the District.[5] With each section of the quilt delicately unfurled, messages, intricate designs, and tributes were spread out before a community desperate to heal. As organizers from the NAMES Project[6] hoped, the quilt served as “a poignant reminder of both the human suffering caused by the [AIDS] epidemic and the dignity and hope of those who remained.”[7]

As the opening event to the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, the inaugural display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt humanized a disease that had been considered, at best, taboo in mainstream culture. When discussing the quilt’s magnitude, one marcher living with AIDS stated that he “didn’t know anyone personally, but it’s not necessary to know people to feel it…In a way, we know them all.”[8]

Over the course of the weekend, nearly 500,000 people flocked to the Mall to see the tapestry and attempt to make sense of the disease.[9] For most, the quilt was a sober reminder of a crisis facing the nation. But for others, it was personal. The consequences of the crisis were hard for Washingtonians to miss. At the time of the March, the Greater Washington area was home to 1,542 reported cases of the disease, which ranked fifth-most among metropolitan areas nationwide.[10]

Still, reliable information about AIDS was hard to come by, particularly in the early days of the crisis. As community member Brian McNaught wrote in 1982, “Because so many of the victims of AIDS have been homosexual and because so little is really known about the diseases, there has been considerable psychological turmoil in the Gay male community. Rumors are flying right and left about who’s got it and how they got it and how not to get it. Because the rumors are generally contradictory and because medical reports are frequently difficult to understand and digest, the problem of understanding AIDS is compounded.”[11]

The Washington Blade, D.C.’s seminal LGBT newspaper, set out to fill the information void before AIDS even had a name. Headlines from as early as 1981 in the Blade reflect the nation’s understanding of an epidemic that was beginning to reveal itself.

“Rare, Fatal Pneumonia Hits Gay Men” and “Task Force to Study Rare Cancer in Gay Men” hid unassumingly within the pages of the Blade, foreshadowing the chaos that would come later. While the mainstream media reduced AIDS to the ‘gay plague’ in the early days of the crisis,[12] the Blade delivered on its masthead promise to provide “Straight Facts, Gay News.,” to Washington. As a part of Washington’s gay community, the Blade did not have the luxury of indifference. “AIDS became a main beat for us. We even had a section of the paper called the ‘AIDS Digest.’ We reported news about AIDS that the mainstream press wasn’t focusing on,” recalled Lou Chibbaro Jr., longtime reporter for the newspaper.[13]

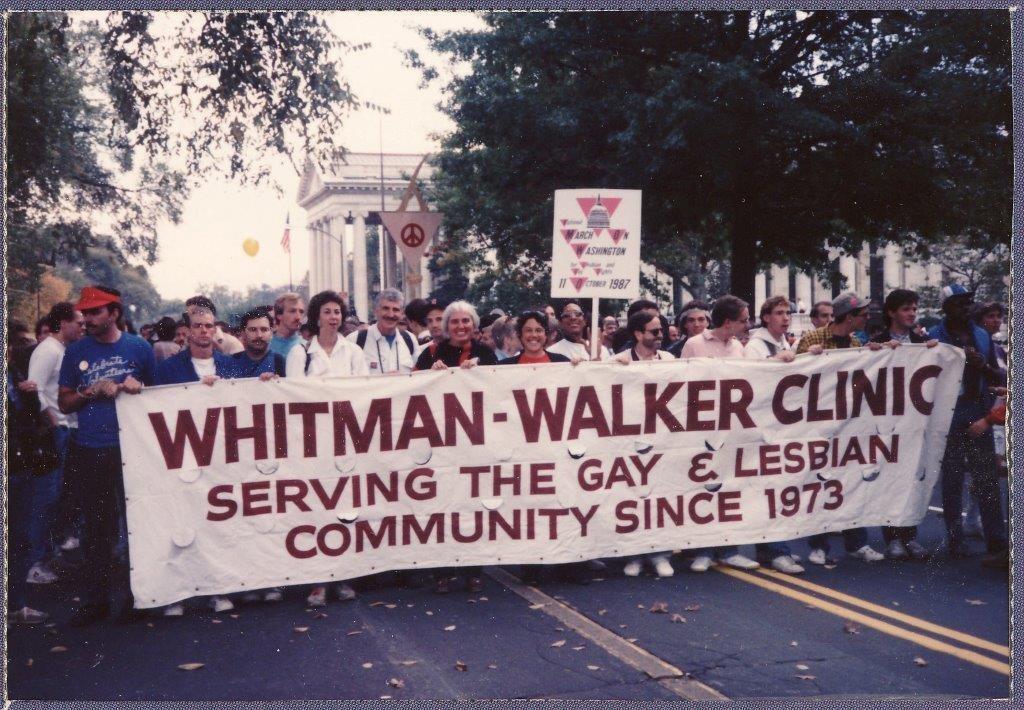

While reliable reporting was essential, it could only go so far in combatting the disease. Those afflicted with AIDS required medical treatment. As the crisis intensified, help came from a familiar place, as long-term AIDS survivor and activist Sean Strub remembered: “When the epidemic hit, a community emerged in New York City. It was different in DC—it was smaller and built around the Whitman-Walker Clinic.”[14]

Founded in 1973, Whitman-Walker began as the Gay Men’s VD Clinic (part of the Washington Free Clinic) in the basement of the Georgetown Lutheran Church. Later rebranding as Whitman-Walker and moving to Adams Morgan, the clinic became ground zero for the gay community as the AIDS crisis reached Washington.[15] The clinic’s service to those living with AIDS and those at risk of contracting AIDS was extensive. Between 1983 and 1986, what was originally a private, part-time clinic dedicated to providing AIDS education and patient support[16] became a full-time clinic for AIDS patient treatment.[17]

Early efforts included creating an AIDS Education Fund, which allowed Whitman-Walker to directly disseminate information to persons living with AIDS in Washington.[18] The clinic’s revolutionary anonymous AIDS Infoline[19] coupled with public forums[20] bolstered these efforts to educate the District. Later, through their AIDS Evaluation Unit, the clinic began diagnosing and treating patients within their offices.[21] Individuals most deeply affected by the disease were invited to live in the clinic’s AIDS group homes.[22] Most notably, in 1985, the Whitman-Walker hosted the first AIDS testing program in the Washington area.[23]

Jim Graham, former head of the clinic, was test number one: “I wanted to show that this was important. It was controversial at the clinic. First, why would you want to know? There was no prospect of any cure, no medication, no vaccine. Just practice safe sex and let it go. Second, there was a stigma and fear about being found out.”[24]

Graham’s words allude to an unfortunate truth. Beyond the physical toll of disease, Washington’s gay community, which already battled discrimination independent of the AIDS crisis, faced other challenges, too. Breakthroughs in research relating to the spread of AIDS were made gradually, leading to misconceptions. High incidences of the disease in hemophiliacs, injection drug users, and—in particular—homosexual men led the public to believe that only certain groups were at risk of HIV and AIDS.[25] This disproportionate affliction within the gay community was seized by the media. Sensationalizing the epidemic as a means to increase readership was not uncommon at the time, even among reputable newspapers. Headlines such as “Mere Contact May Spread AIDS” fueled public hysteria[26], and the epidemic continued to be viewed by many as specifically a gay problem.

Leonard P. Matlovich, who moved to the District after being discharged from the Air Force for his homosexuality, voiced his frustration to The Washington Post in 1985. “There is no AIDS problem in America until it leaves the gay community and goes into mainstream America. Then it will be too late.”[27] To combat public indifference, the Washington, D.C. area became home to groups and activists outside of the Whitman-Walker Clinic, now Whitman-Walker Health, dedicated to supporting those living with AIDS and the LGBT community at large.[28] These organizations, such as the DC AIDS Task Force, Us Helping Us, Brother Help Thyself, local churches, political groups, and so many more, worked tirelessly to provide acceptance, gain visibility, forward AIDS research efforts, and encourage action in the fight against AIDS on a national scale.

Even as activists in Washington worked to overcome the AIDS crisis locally, the District’s most powerful resident, President Ronald Reagan, remained tight-lipped on the subject until well into his second term in office.[29] Reagan was, according to his supporters, waging a quiet war against AIDS by strategically appointing others, like the FDA, to fight the disease.[30] Sean Strub remembers the silence differently: “With Reagan, there was intentional neglect. Jesse Helms and Jerry Falwell had just come into prominence, so there was all this anti-gay sentiment: [AIDS] was nature doing its housecleaning.”[31] Whether Reagan was truly indifferent remains unclear, but an old friend from Hollywood left no room for uncertainty with respect to her involvement. Elizabeth Taylor’s reputation as a crusader in fighting HIV and AIDS almost eclipses her reputation as a serial monogamist.

As AIDS reports surfaced, Taylor was flummoxed. “I kept seeing all these news reports on this new disease and kept asking myself why no one was doing anything. And then I realized I was just like them. I wasn’t doing anything to help,” she recalled later.[32] The opportunity to do something came quickly. Taylor -- whose longtime friend and Giant co-star Rock Hudson had contracted AIDS -- signed on as chairman of the first major AIDS benefit in the nation in June 1985, the Commitment to Life dinner held in Los Angeles.[33] She helped raise an unprecedented $1 million for the beneficiaries of this event, AIDS Project Los Angeles.[34] This was only the beginning of Elizabeth Taylor's work toward ending the epidemic.

Taylor co-founded the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) and served as their national chairman.[35] In this way, Liz was able to, as a 1992 Vanity Fair profile put it, bring AIDS “out of the closet and into the ballroom, where there was money—and consciousness—to be raised.”[36] In a now-famous letter, she requested that President Reagan join the effort.

On April 10, 1987, Taylor wrote from the heart. She asked Reagan to attend and deliver the keynote speech at a dinner hosted by amfAR, asserting that, “It would do so much for us the get rid of the archaic stigma attached to the disease and to make people realize that it is no longer a minority disease; it can happen to anyone. It’s nobody’s fault and everybody’s problem.”[37] Seven weeks later, on May 31, 1987, Reagan honored Taylor’s request. In front of 850 AIDS activists, philanthropists, and amfAR representatives at the Potomac Restaurant in Washington, he spoke about AIDS for only the second time in his tenure as Commander and Chief, eight years into the AIDS crisis. Reagan was met with a chorus of boos from attendees after calling for routine testing for HIV/AIDS,[38] which the community opposed for fear of discrimination, but his engagement in the conversation about the AIDS epidemic eventually garnered applause.

Just five months later, nearly a half million activists and visitors descended on Washington, D.C.[39] As notices about individuals who ‘died from complications associated with AIDS’ populated the obituaries section of the Washington Blade and waiting rooms filled at the Whitman-Walker Clinic, friends, family members, and supporters used their frustration, sorrow, and hope to create a mammoth memorial that honored those already lost to the AIDS epidemic. Despite the fact that an AIDS diagnosis was no less than a death sentence in the 1980s and incidents of the syndrome were growing exponentially, it was a pivotal moment. These activists wrapped Washington, D.C. in the AIDS Memorial Quilt to signify their refusal to be left out in the cold.

Footnotes

- ^ Betsy Pisik, “A Solemn Silence Surrounded the Mammoth AIDS Quilt,” Washington Blade, October 16, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Sandra G. Boodman, “A Somber Crowd Dedicates Quilt to AIDS Victims,” Washington Post, October 12, 1987, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Betsy Pisik, “A Solemn Silence Surrounded the Mammoth AIDS Quilt,” Washington Blade, October 16, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Sandra G. Boodman, “A Somber Crowd Dedicates Quilt to AIDS Victims,” Washington Post, October 12, 1987, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Inaugural Display,” Washington Blade, October 11, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ “History of the Quilt,” The NAMES Project Foundation, aidsquilt.org. Cleve Jones, San Franciscan and devoted gay rights activist, founded the NAMES Project and conceived the idea for the AIDS Memorial Quilt in 1985. When planning the annual memorial march for gay San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone that year, he asked fellow-marchers to write the names of those they had lost to AIDS on placards for display. When considering a larger scale memorial, Jones and fellow-activist Mike Smith devised the plan for a quilt. The NAMES Project organizers spread the word about the Quilt, to which Jones contributed the first panel, around the U.S. cities most affected by AIDS, and, soon, hundreds of panels arrived at their San Francisco workshop. Volunteers helped construct the Quilt, and donations allowed for the transportation of the memorial.

- ^ “Inaugural Display,” Washington Blade, October 11, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Betsy Pisik, “A Solemn Silence Surrounded the Mammoth AIDS Quilt,” Washington Blade, October 16, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Lisa M. Keen, “The National March Takes Washington by Surprise,” Washington Blade, October 16, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Robert Blizard, “271 New Cases Since August,” November 13, 1987

- ^ Brian McNaught, “AIDS: When Tragedy Strikes,” Washington Blade, October 8, 1982, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ German Lopez, “The Reagan Administration’s Unbelievable Response to the HIV/AIDS Epidemic,” Vox, December 1, 2016, Vox.com.

- ^ Dave Singleton, “Anniversary of AIDS in Washington: 30 Years Later,” Washingtonian, June 24, 2011, Washingtonian.com. Some of the paper’s standout offerings include a six-part series that explained and contextualized AIDS in 1983, weekly interviews with prominent D.C. attorney Ray Engebretsen as he died of AIDS in 1985, and a continued commitment to dignify AIDS victims through honesty in their obituaries.

- ^ Dave Singleton, “Anniversary of AIDS in Washington: 30 Years Later,” Washingtonian, June 24, 2011, Washingtonian.com

- ^ “Our History,” Whitman-Walker Health, 2012, Whitman-walker.org.

- ^ Margaret Engel, “Private NW Clinic Has Support Plan For Victims of AIDS,” Washington Post, September 22, 1983, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Margaret Engel, “Full-Time Clinic to Treat AIDS Planned in D.C.,” Washington Post, September 6, 1986, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Our History,” Whitman-Walker Health, 2012, Whitman-walker.org.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Lisa M. Keen, “AIDS Forum Draws 1,200,” Washington Blade, April 8, 1983, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ “Our History,” Whitman-Walker Health, 2012, Whitman-walker.org.

- ^ Tam Cummings, “Schwartz House Officials Meet with Neighborhood,” Washington Blade, December 21, 1984, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Dave Singleton, “Anniversary of AIDS in Washington: 30 Years Later,” Washingtonian, June 24, 2011, Washingtonian.com

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Margot Joan Fromer, “AIDS: Mystery Illness Leaves Its Victims—Most of them Urban Gay Men—Virtually Defenseless,” Washington Blade, January 14, 1983, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Larry Bush, “Media Hype: Business as Usual is Not Good Journalism,” Washington Blade, July 1, 1983, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Marcia Slacum Green, “Initiatives Aim at AIDS Virus: Baths Would Be Regulated” Washington Post, March 8, 1985, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “The ‘80s: The Decade in Review,” Washington Blade, December 29, 1989, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Dave Singleton, “Anniversary of AIDS in Washington: 30 Years Later,” Washingtonian, June 24, 2011, Washingtonian.com.

- ^ Peter W. Huber, “Ronald Reagan’s Quiet War on AIDS,” City Journal, Autumn 2016, City-journal.com.

- ^ Dave Singleton, “Anniversary of AIDS in Washington: 30 Years Later,” Washingtonian, June 24, 2011, Washingtonian.com.

- ^ “Dame Elizabeth Taylor: Founding International Chairman,” amfAR, amfAR.org.

- ^ From the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation: Elizabeth was asked to spearhead APLA’s effort to raise $500,000 and be the honorary host for the first Commitment To Life event on June 4, 1985. She asked her publicist and close friend, Chen Sam who worked out of New York, to rent a temporary office in Los Angeles where they worked full time on the event.

- ^ Nancy Collins, “Liz’s AIDS Odyssey,” Vanity Fair, November 1992, Vanityfair.com.

- ^ From the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation: Elizabeth and Dr. Michael Gottlieb started the National AIDS Research Foundation (NARF) with $250,000 that Rock Hudson left to them for that purpose. Dr. Gottlieb is the physician who first described the new disease that would later become known as AIDS. He was treating Rock and that’s how Elizabeth met him. David Geffen was also involved in the AIDS crisis and he was friends with Arthur and Dr. Mathilde Krim, along with Elizabeth. Mathilde had started an AIDS research foundation in New York. Geffen felt that between Elizabeth’s huge fame and Mathilde’s scientific background, they would make a powerful combination and he was right. So the two organizations were combined to create the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). The co-founding members were Elizabeth Taylor, Dr. Mathilde Krim and Michael Gottlieb.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/aids/docs/taylor.html

- ^ Lisa M. Keen, “Reagan v. Taylor: Speeches Mirror Debate Over AIDS,” Washington Blade, June 5, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

- ^ Lisa M. Keen, “The National March Takes Washington by Surprise,” Washington Blade, October 16, 1987, DC Public Library: Washington Blade.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)