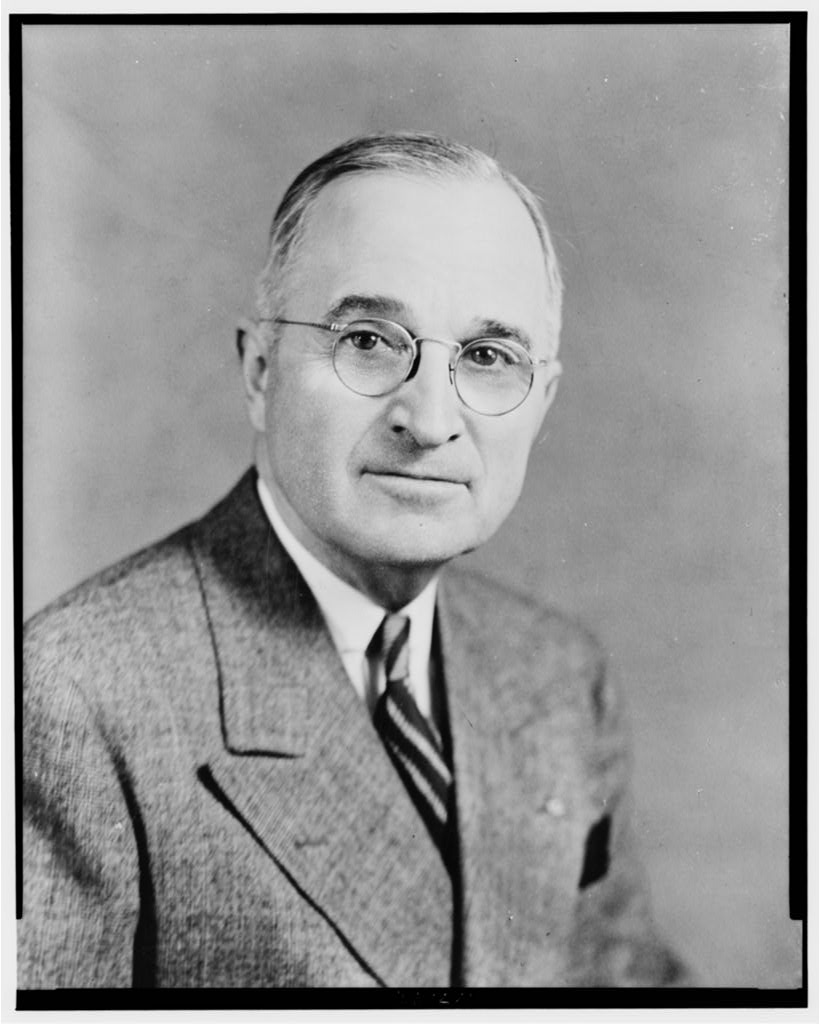

President Truman's Close Call at Blair House

November 1, 1950 was an unseasonably warm fall day in Washington. Thermometers reached 85 degrees by early afternoon, and White House Police officers wiped away beads of sweat as they stood guard outside of Blair House, the temporary residence for the first family while the White House was undergoing renovations.

President Truman, due to make an appearance at Arlington National Cemetery later that afternoon, laid down for a nap around 2pm. Across town, taxi driver John Gavounas had just picked up two men at North Capitol St. and Massachusetts Ave. The fares instructed him to take them to 17th and Pennsylvania Ave., NW, and then spent the ride talking to each other in Spanish. The only word that Gavounas recognized was “Truman.” As the cabbie recalled later, the passengers “acted very gentlemanly” and tipped well when he dropped them off around 2:15pm.[1] Upon exiting the cab, the passengers, who the world would soon learn were Oscar Collazo and Griselo Torresola, split up.

Back at Blair House, the guards were in the midst of a shift rotation. Enhanced security measures for the President’s stay had put two security booths on the sidewalk, on either side of the home’s entrance. Additional officers were stationed on the front steps.

As tourists wandered by, Torresola and Collazo approached Blair House from opposite directions.[2] Coming from the west, Torresola paused in front of the guard booth and addressed the guards loudly. Meanwhile, Collazo slipped by the eastern booth, drawing an automatic P-38 Walther pistol from his waistband as he approached the steps. Taking aim at officer Donald Birdzell, who was apparently focused on Torresola’s diversion, Collazo pulled the trigger.

Click… A misfire.

Hearing the noise, Birdzell turned to see Collazo’s gun raised, just as he fired again. This time the weapon discharged, and Birdzell was hit in leg.

In an instant, the street erupted in gunfire. Birdzell drew his weapon and shot at Collazo while limping toward the street, apparently trying to draw the bullets away from the building. Meanwhile, Torresola shot Officer Leslie Coffelt from close range as he sat in the western guard booth. Torresola then turned to hit Officer Joseph Downs by the basement steps as Downs scrambled inside to alert the Secret Service.

Hearing the commotion below, President Truman came to his third floor window, only to retreat when one of the policemen screamed, “Get back.”[3] From their position in the eastern guard booth, Officers Joseph Davidson and Floyd Boring fired at Collazo, who was wounded and fell to the sidewalk. Then, as Torresola took aim at Birdzell, a dying Coffelt raised his gun and shot him through the head. Falling into the Blair House hedges, Torresola died instantly. (See diagram of gun battle.)

Just like that it was over.

Truman was quick to downplay the attack. When aids asked whether he still intended to make his scheduled appearance at Arlington Cemetery, the President responded, “Why, certainly.”[4] (He did, indeed, go to Arlington.) Later, he called the gunmen “as stupid as can be,” quipping, “I know I could organize a better program than they put on.”[5] It was gallows humor, but the President had a point. His plans to visit Arlington had been publicized in the Washington papers. So, if the Collazo and Torresola had waited about twenty minutes, the President would have walked right out on the street to meet them on the way to his motorcade.

Police, of course, took the incident very seriously and immediately set out to piece together what had happened. From his hospital bed at Emergency Hospital, Collazo was eager to provide details.

“We came here for the express purpose of shooting the President,” he said.[6]

Calling himself a martyr, he told police that he and Torresola were Puerto Rican Nationalists. Their attempt to kill Truman was an effort to start a revolution in the U.S. and win independence for Puerto Rico. He accused the United States of enslaving his countrymen and making Puerto Rican politicians “tools” of the U.S.[7] (The island nation had been a U.S. territory since the Spanish American War, 50 years prior, and had been governed by a presidentially-appointed governor and executive council, a legislature, and a judicial branch.)

According to Collazo, the two would-be assassins had hatched the plot two weeks earlier in New York. Collazo had little experience with guns, so Torresola had taught him how to load and handle a weapon.[8] On the day before the assault, they had taken a train to D.C. and spent the night in the Harris Hotel near Union Station, where they checked in separately using fake names – Collazo was “Anthony DeSilva” and Torresola was “Charles Gonzalez.”[9] Collazo denied any connection to communism – an important question in the midst of the red scare – and claimed that they had hatched the plot by themselves.

Sadly, Officer Coffelt succumbed to his injuries and passed away in the hospital. The President expressed his condolences. “I wasn’t in any danger—never have been—but it was a terrible thing to have one of the finest fellows you ever knew murdered outright…. It just makes you sick.”[10] Truman also struggled to understand the motives of the gunmen, telling the Evening Star, “Puerto Rico has had the best treatment in this administration it has ever had in its history. They’ve got free government and their own government.”[11] The statement was likely a reference to the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act, which he had signed a few months earlier. That legislation cleared the way for Puerto Ricans to organize a local government and ratify their own constitution, which would be finalized in 1952.

For Collazo and Torresola, however, such policy changes were immaterial. They wanted full independence and Truman represented a barrier. As Collazo said after his arrest, “Truman was… just a symbol of the system…. You don’t attack the man, you attack the system.”[12]

Though Truman seemed eager to move past the incident and resume his normal routine, the episode prompted changes to security procedures. The President would no longer be permitted to walk between Blair House and the West Wing. Instead he would be driven back and forth in a bulletproof car.[13]

Truman lamented the new policies in his diary a few days later: “Because two crackpots or crazy men tried to shoot me a few days ago my good and efficient guards are nervous. So I’m trying to be as helpful as I can. Would like very much to take a walk this morning but the S[ecret] S[ervice]… and the 'Boss' and Margie are worried about me—so I won’t take my usual walk. It’s hell to be President.”[14]

In 1952, Oscar Callazo was sentenced to death for his role in the attack but one week before his execution, Truman commuted the sentence to life in prison. In 1979, President Carter commuted the life sentence and Callazo was freed. He died in Puerto Rico on February 20, 1994.

Footnotes

- ^ Bradlee, Benjamin. “Blair Killings Described to Grand Jury: 12 Witnesses Testify; Cabbie Says He Took Gunmen to Death Site Blair Killings Are Described.” The Washington Post (1923-1954); Washington, D.C. November 9, 1950.

- ^ McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, 809-811.

- ^ Andrews, Marshall. “Truman Goes Calmly to Rites For Dill After Killings.” The Washington Post (1923-1954); Washington, D.C. November 2, 1950.

- ^ Andrews, Marshall. “Truman Goes Calmly to Rites For Dill After Killings.” The Washington Post (1923-1954); Washington, D.C. November 2, 1950.

- ^ McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- ^ “Truman Plotter Faces Execution; Puerto Rico Siezes Rebel Chiefs: Move Smashed; Guard Bolstered at Blair House.” Evening Star, November 2, 1950.

- ^ “Truman Plotter Faces Execution; Puerto Rico Siezes Rebel Chiefs: Move Smashed; Guard Bolstered at Blair House.” Evening Star, November 2, 1950.

- ^ “FAQ: Assassination Attempt on President Truman’s Life.” Harry S. Truman Presidential Library & Museum. Accessed October 30, 2018. https://www.trumanlibrary.org/trivia/assassin.htm.

- ^ Reiff, Jean, and Alfred E. Lewis. “Truman Plot Related by Collazo; Says He’s a ‘Hero’: Assassin Tells Of Hatching Plan With Torresola; Charged in Slaying Gunman Confesses His Part In Plot to Kill President.” The Washington Post (1923-1954); Washington, D.C. November 3, 1950.

- ^ “Truman Feels ‘Sick’ Over Coffelt Slaying in Defending Him,” Evening Star, November 2, 1950.

- ^ “Truman Feels ‘Sick’ Over Coffelt Slaying in Defending Him,” Evening Star, November 2, 1950.

- ^ McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, 812.

- ^ McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, 813.

- ^ McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, 813.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)