Ethel Payne: First Lady of the Black Press

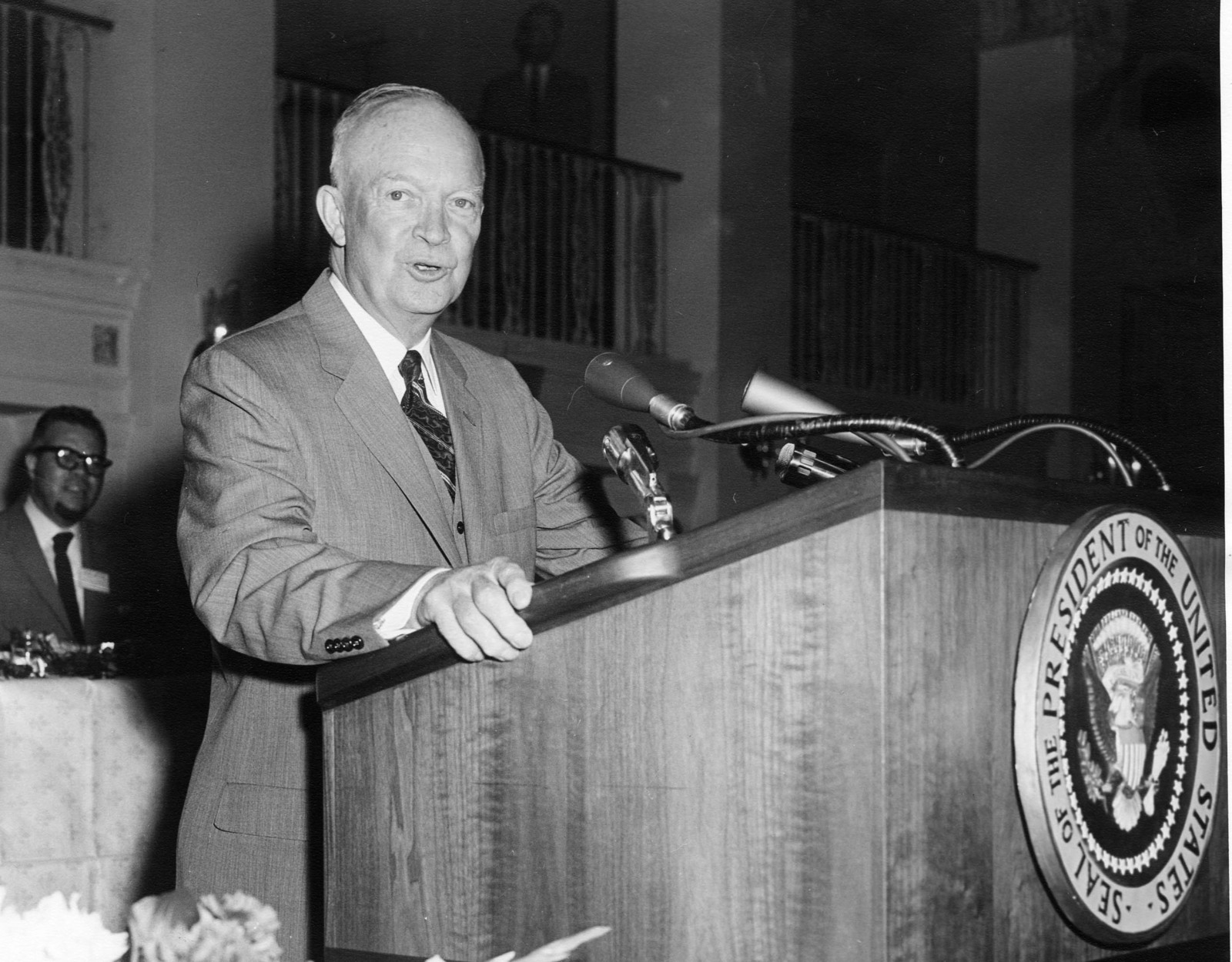

The year 1954 brought many changes, including the historic Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education ruling and increasing of the civil rights movement by the mainstream white media. Change often comes with friction though, as Black female reporter Ethel Payne was reminded on July 7, 1954, when her question pushed then President Dwight Eisenhower a bit too far – at least in his mind.

“Mr. President, we were very happy last week when the deputy attorney general sent a communication to the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee saying there was a legal basis for passing a law to ban segregation in interstate travel…I would like to know if we could assume that we have administration support in getting action on this?”[1] Payne asked when Eisenhower called on her at a White House news conference. She later remembered, “I remember my knees knocking and my voice quavering as Ike cupped a hand to his ear and asked me to repeat.”[2] The question, prepared by Payne and NAACP chief lobbyist Clarence Mitchell, evidently struck a nerve.

Eisenhower snapped back, “You say that you have to have administrative support? The administration is trying to do what it thinks and believes to be decent and just in this country, and is not in the effort to support any particular or special group of any kind.”[3]

The incident caused an uproar amongst the press, many criticizing Payne’s choice to asked such a ‘loaded’ question. Fellow reporter Alice Dunnigan, one of the few that stood up for Payne, described, “The President’s lack of knowledge on many racial issues, raised by reporters of Negro newspapers, seems to have become embarrassing after awhile, and his impatience began to show.”[4] Dunnigan also commented on critiques that Payne received from within the Black journalism community. Harry McAlpin, the only other Black reporter in the White House press corps besides Payne and Dunnigan, was particularly critical of Payne’s questioning. Dunnigan reported: “This unethical journalistic action has resulted in a running word battle between the man reporter [referring to McAlpin] and those who would dare speak out in defense of the women [Payne and herself].”[5]

Payne’s response was to assert her views of what journalism, specifically in the Black press should be. “I stick to my firm, unshakeable belief that the black press is an advocacy press, and that I, as a part of that press, can’t afford the luxury of being unbiased…when it comes to issues that really affect my people, and I plead guilty, because I think that I am an instrument of change.”[6] The issue over objectivity in journalism is still debated the journalistic community today, but Payne was very up front – an unapologetic – about how her experiences as a Black woman living in America informed her writing.

Ethel Lois Payne was born in 1911 in the South side of Chicago, Illinois to William A. Payne and Bessie August Payne. She enjoyed reading, especially the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar, and was one of the first students to integrate Lindblom High School.[7] While at high school, she was not allowed to work for her school newspaper due to the color of her skin. She faced similar discrimination when she was denied admission to the University of Chicago law school because of her race.[8] These experiences shaped Payne into the advocate she was, determined to make space for Black people in white institutions. Payne’s nephew James Johnson, Jr. commented on the situation at the time, “You couldn’t control your opportunities, so you had to be prepared for whatever opportunity came along.”[9]

In 1948, she left Chicago and went to work as a hostess at the Army Special Services club in Tokyo, Japan.[10] She kept a journal while she was there, noting the poor treatment of African-American troops and the shunning of children of Japanese and African-American descent. Specifically, she noted that although President Truman had issued an executive order to integrate the troops, General McArthur had ignored it. While in Japan, Payne met Chicago Defender reporter Alex Wilson, who asked to send her work back to the Defender after reading through her journal. Payne agreed, and the Chief of the Defender offered her a full-time position in 1951.[11]

Her work about the African-American soldiers received pushback once published in the Defender, with people decrying it because it was supposedly “upsetting the morale of the troops.”[12] It would not be the first time Payne faced pushback for her frank style of writing and her ‘agenda,’ but she never let the critics affect her.

Payne moved to D.C. to work as a political correspondent for the Defender in 1953. John H. Sengstacke, editor and publisher of the Defender said of the assignment: “We purposefully waited to fill the Washington assignment in our organization until we were satisfied that we had a person capable of doing the same superb job of giving our readers the most accurate coverage possible of the Washington scene in the same excellent manner as Mrs. Spraggs and Al Smith who preceded her. The Defender has always been known to have had the best available persons to represent it in Washington. I am confident that Miss Payne is such a person.”[13]

D.C. further reminded Payne why her advocacy work was important. Biographer James McGrath Morris wrote: “As a correspondent in Washington, merely getting from her apartment to the White House could be a problem because a cab might not pick her up, as an African American.”[14] Her relationship with Eisenhower was not rocky at first, Morris said. “Eisenhower at first called on her repeatedly. And, at this point, she was discovering that asking a question at a national press conference, having a seat at the table, if you wish, made a huge difference, because when she asked a question, it forced the mainstream, i.e., white media, to report on an issue, civil rights, that they were ignoring.”[15] Eventually though, her questions about the discrimination Black people faced in D.C. and America at large began to grate on him, resulting in the infamous incident.[16]

After the incident, Eisenhower refused to call on Payne at press conferences. She later wrote, “I got the silent treatment for weeks at the news conferences, though I never stopped going.”[17] The struggle didn’t end there though. White House press secretary James Hagerty, taking matters into his own hands, searched for a way to revoke Payne’s White House accreditation by looking at her income tax returns.[18] A Baltimore Afro-American article reported that he even summoned her to the White House to warn her about asking further questions in the vein of her inquiry about Eisenhower’s support for banning segregation in interstate travel.[19]

During this time, Payne turned her gaze away from the White House and towards other civil rights issues. In 1955, she was the only Black correspondent at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, the first large-scale conference between Asian and African states, many of which were newly independent. Her interest in international affairs stemmed from her strong belief that international affairs and civil rights were deeply connected.[20] After returning home from abroad, Payne also began to cover the civil rights movement in the South, becoming one of the first reporters to talk about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.[21] She described him and the new angle of the movement: “Instead, this gladiator going into battle wears a reverse collar, a flowing robe, and carries a Bible in his hand.”[22]

Payne’s keen eye and frank writing style ruffled feathers, but also allowed her to report honestly on what she saw and she covered many historic moments from her home in Columbia Heights.[23] “The white press was so busy asking questions on other issues that the Blacks and their problems were completely ignored.” She reflected later.[24]

Throughout the sixties, she continued to report on civil rights events in D.C. President Lyndon B. Johnson even invited her to the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, where he also gifted her one of the pens used for the signing.[25] She earned an award from the Capital Press Club in 1967 for her work on the Vietnam War, the second she had earned from them.[26] She also wrote about how Dr. King advocated for sit-ins in D.C. in response to housing conditions, which would later evolve into the infamous Poor People’s Campaign of 1968. Payne described King as “the leading apostle of nonviolence,” a vivid image reflective of her writing skills.[27]

In 1972, she was hired by CBS and became the first Black woman radio and television commentator on a national network, a position that paved the way for others who looked like her.[28] Morris noted “I met a man who became an anchor in several major markets, an African-American male who is now retired, and he said, when he saw her on TV, he realized that that career was possible.”[29] She continued to work for the Chicago Defender and CBS for many years, eventually earning her way into the D.C. Women’s Hall of Fame in 1988. Payne continued to stand up for other Black writers, even lamenting about fellow reporter Alice Dunnigan’s lack of notoriety. “The late Alice Dunnigan who was the first black woman to be accredited as a White House correspondent, and whose experiences spanned a rich period in American history, tried in vain to have her manuscript accepted for publication. Finally, she had to personally underwrite her 671-page tome and assume the burdensome task of marketing it herself at a great sacrifice.”[30]

Throughout her long career, Payne faced many critics, many of whom found issue with her unwillingness to be “objective.” A 1974 Defender article summarized it best: “Ethel’s romance with the Black press is passionate, and some of her colleagues condemn her for championing the causes of the little man at the expense of 'objectivity' – one of journalism’s touted canons that gives no room for a reporter’s emotions and politics.”[31] They never stopped her from reporting what she felt to be true though. Yet, despite Payne’s many accomplishments and contributions to the journalistic community, not many know about her. After her death in 1991, The Washington Post gave a frank answer to the conundrum, writing: “Had Ethel Payne not been black, she certainly would have been one of the most recognized journalists in American society.”[32]

Footnotes

- ^ Morris, James McGrath. “Ethel Payne, ‘first lady of the black press, ‘asked questions no one else would.” The Washington Post. The Washington Post Inc. August 12, 2011.

- ^ Payne, Ethel L. "Eisenhower as Ethel Payne Knew Him." Chicago Daily Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1966-1973), Apr 05, 1969, (accessed August 12, 2022).

- ^ Morris, “Ethel Payne.”

- ^ Dunnigan, Alice A. "Why Press Query Fired Ike's Ire." The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jul 24, 1954, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Morris, "Ethel Payne."

- ^ Golden, Jamie Nesbitt. “Chicago’s Ethel Payne, ‘First Lady of The Black Press,’ Is Buried In An Unmarked Grave — But A Historian Is Working To Change That.” Block Club Chicago. Block Club Chicago. October 18, 2021.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “First two Black women in White House press corps honored with lifetime achievement awards.” CBS News. CBS Interactive Inc. April 29, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Ashlee. “Ethel L. Payne.” National Women’s History Museum. PwC Charitable Foundation. 2018.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Ethel Payne to Cover Capital for Defender." The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Nov 28, 1953, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ PBS NewsHour. “Black journalist Ethel Payne changed the national agenda with coverage of civil rights.” YouTube Video. 6:33. February 26, 2015.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Anderson, “Ethel L. Payne.”

- ^ Payne, Ethel L. "Eisenhower as Ethel Payne Knew Him." Chicago Daily Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1966-1973), Apr 05, 1969, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Anderson, “Ethel L. Payne.”

- ^ "Why does Ike Snub Colored Reporters?" Afro-American (1893-), Apr 27, 1957, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Levy, “Journalist Ethel Payne Dies.”

- ^ Morris, “Ethel Payne.”

- ^ DC Historic Preservation Office, “Civil Rights Tour: Civic Activism - Ethel Payne, Washington Correspondent,” DC Historic Sites, accessed August 10, 2022.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Golden, “Chicago’s Ethel Payne.”

- ^ "Ethel Payne Wins Press Club Award." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Jun 14, 1967, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ ETHEL, PAYNE CORRESPONDENT. "King Wants Congress to Act on Ghettos: Advocates Massive Sit-in in Capital." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Oct 25, 1967, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ Gibson, Tammy. “Forgotten Heroine, Ethel Payne: Pioneer of the Black Press.” Chicago Defender. Real Times Media. October 8, 2021.

- ^ Morris, “Ethel Payne.”

- ^ "ETHEL PAYNE: BEHIND THE SCENES THE STRUGGLE FOR RECOGNITION BLACK WOMEN WRITERS." Afro-American (1893-), Dec 14, 1985, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ "Have You Met Miss Payne?" Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1973-), Mar 30, 1974, (accessed August 10, 2022).

- ^ “Ethel Lois Payne,” The Washington Post. Washington Post Inc. June 2, 1991. The Post article credits Howard University journalism professor Raymond H. Boone for this observation.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)