The National Mall was Once Home to a Huge Government Fish Farm That Wreaked Havoc on US Fisheries

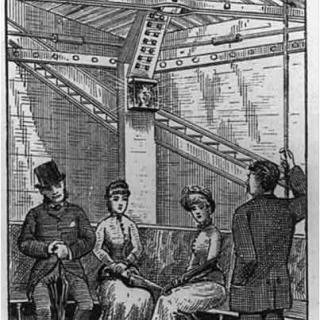

“It is one of the most attractive and interesting features of the city, these carp ponds. The grounds are so pleasant and well kept. The solid sod slopes so greenly down to the water and in these early spring days one would rather sit on the grass in the sunshine than to breathe the breath of the galleries and listen to Congressional debate. The sun shines; the warm cloudy water is full of lights and shadows; there is a dandelion within reach; the flags in the water are taking on new shades of green; now and then there is a flash of a fin and a shy carp swims away from you—a phantom fish of whose exact species you are painfully uncertain.” –The Washington Post, 1880[1]

Where is this Eden in the District of Columbia, brimming with blooming flowers, blanketed by lush lawns of bright green grass, and filled with silver carp lazing in tranquil waters? Well, it exists only in Washington’s past. Washington D.C. has its hidden gems, but none perhaps as hidden as the long-gone and long-forgotten carp ponds that were once a main attraction on the National Mall for close to thirty years. But you’ve probably never heard of them, and the U.S. government is happy about that.

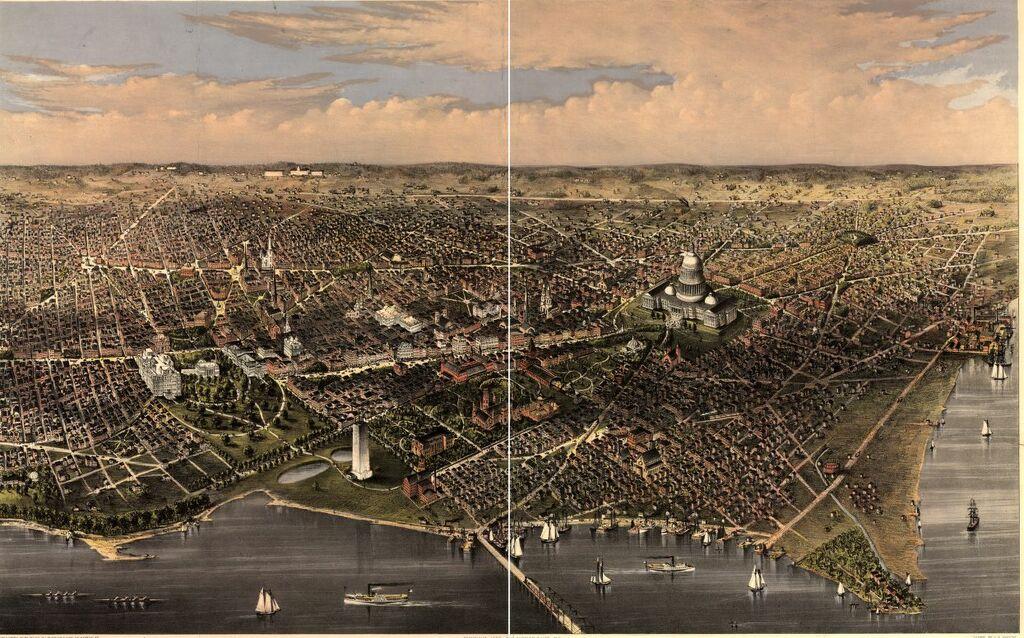

The carp ponds entered Washington’s landscape under the direction of the first commissioner of the United States Fish Commission, Professor Spencer F. Baird.[2] Created by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871,[3] the Fish Commission’s chief aim was “to stock the depleted waters of the United States with fish” after overfishing had dramatically reduced food fish populations across the nation.[4] Baird devised a plan to create a series of ponds within Washington, D.C. to breed and raise fish for distribution across the country. As the curator of the Smithsonian, Baird was familiar with the National Mall, so he proposed adapting the land around the emerging Washington Monument for his fisheries project. The 45th Congress agreed and provided $5,000 toward the effort in 1877.[5]

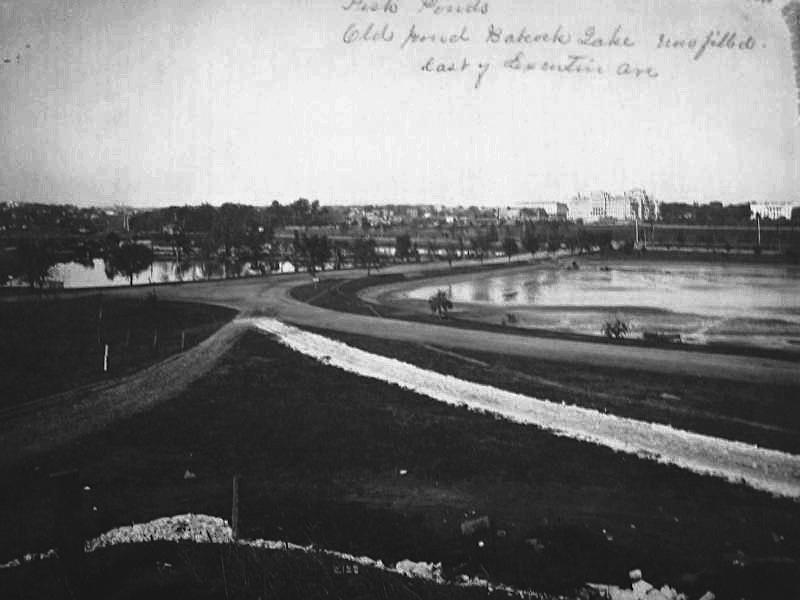

By 1878, construction of the fish ponds, originally called Babcock Lakes, began. Using material from Ripp’s Island, a small stretch of land in the historic Tiber Creek that flowed just north of the Washington Monument, two shallow breeding ponds were carved out and prepared for filling.[6]The finny inhabitants to occupy this prime D.C. real estate were so-called German carp, which were actually from Asia originally and not native to North America (or Europe for that matter).[7] Professor Baird selected the Teutonic pilgrims on merit. In Germany, carp had been successfully farmed and were known for their swift adaption to small spaces, low feeding costs, speedy propagation, and their ability to be “fattened like pigs to a great weight in a short amount of time,” according to the Evening Star, the apparent leaders of the piscine press.[8] (No, seriously. The Star ran HUNDREDS of carp-ticles during Washington’s thirty-year fish frenzy. Their news coverage was practically pescatarian. Carpe carpium, I guess.)

In 1877, a shipment of 65 German carp[9] safely arrived in Baltimore, where the new citizens were quickly naturalized after their trans-Atlantic journey.[10] The batch included three species—leather carp, mirror carp, and common carp—and all flourished under the watchful eye of Mr. Rudolph Hessel, a German scientist who became superintendent of the Monument ponds. Hessel transferred the carp to their headquarters on the National Mall when Babcock Lakes were ready for inhabitants,[11] where each species spawned in separate areas within the ponds, accompanied by European tench, the gold Ide, bass, crappie, and even a small cohort of turtles.[12]

The fish adjusted well to life in the District according to the Washington Post: “The carp ponds are bounded on the north by the White lot and the White House grounds and on the south by the [Potomac] river, and when some immense carp, in sheer ecstasy of wellbeing, leaps of for one shining minute into the sunshine, he sees the new State Department and the Treasury, the somber towers of the Smithsonian, and the more sensational rotunda of the new National Museum. And in the water or out of the water, he is always aware of the Washington Monument.”[13]

With an enviable view of the growing and changing National Mall, the young carp flourished as Professor Baird had hoped.[14] By the end of 1880—after only a single spawning season—an estimated 100,000 carp resided in the murky waters of Babcock Lakes.[15] This total excludes the estimated 350,000 fish that the U.S. Fish Commission had already extracted and distributed to eager communities throughout the country.[16] The Commission filled large tin cans with batches of carp and shipped them all over the U.S. in packed railroad cars. Accompanied by travelling agents, the carp made their way to New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Connecticut, Tennessee, Georgia, and Texas in the first year, with the promise of restoring depleted waters.[17]

America’s appetite for Mall carp was insatiable. Applications arrived daily to Baird’s office requesting shipments of all sizes. From stocks that would fill private ponds to supplies that could populate entire states’ reservoirs, the Fish Commission filled thousands of orders for little more than a written request to one’s congressman and payment for the cost of shipping.[18] Thousands of other orders went unfilled as the Fish Commission struggled to keep up with demand. Although the carp were known to thrive in southern waters more so than northern waters, Professor Baird would procure a shipment of his precious poissons to be delivered anywhere the railroads could take them.[19]

With such tremendous success, expansion of the ponds became inevitable. The original Babcock Lakes covered only about 12 acres across two ponds.[20] An additional 8-acre pond would bring the total to 20 acres by 1881, as Prof. Baird discussed further expansion.[21]

It was not all smooth swimming for the carp, however. With the 36-year construction of the Washington Monument finally completed in 1884, the fate of Babcock Lakes became uncertain. Engineers worried that the lakes contributed to alarming settling on the north side of the Washington Monument.[22] Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey, who oversaw the completion of the Monument, explained that, while the existence of the lakes didn’t necessarily threaten the stability of the monument, he believed the fish ponds “should be done away with for precautionary reasons.”[23] On this basis, the Senate approved the closure of Babcock Lakes during the spring of 1887.[24]

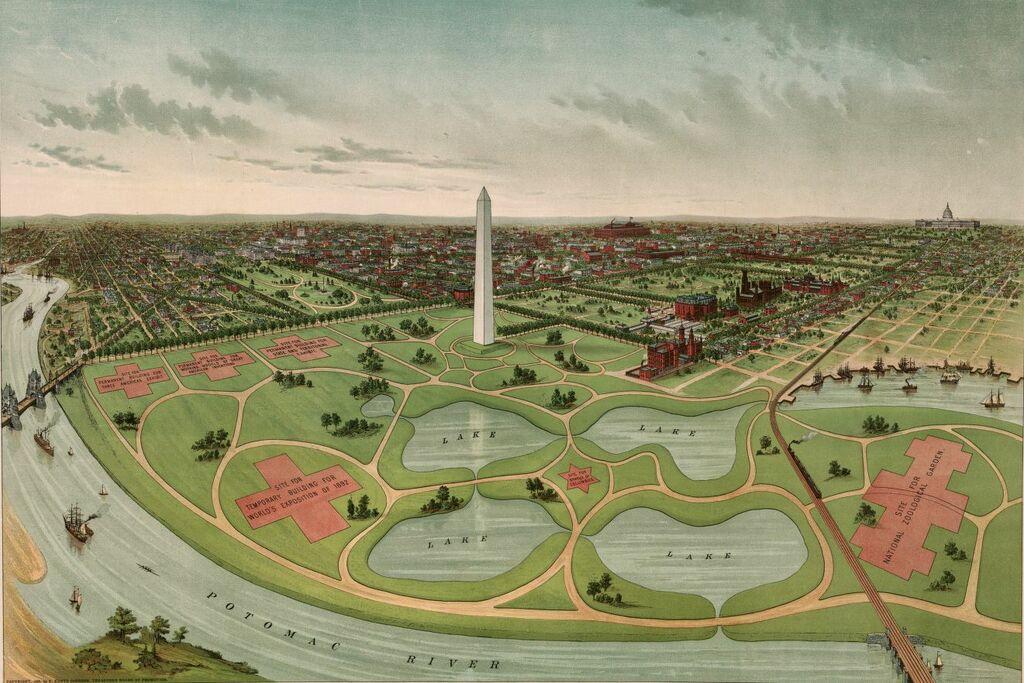

To continue the breeding operation, four new lakes were created where the Tidal Basin now sits by 1888.[25] A year later, however, the all-too-common floods on the banks of the Potomac River swept a reported 4,000,000 youthful fishes out of their nursery ponds into the raging waters of the Potomac. It was a “catastrophe by which millions of innocent creatures, as yet too young to know their dorsal from their ventral fins, were engulfed in an irresistible torrent rushing toward the sea,” mourned the Evening Star.[26]

Despite these challenges, 300,000 carp were still distributed annually from the Mall ponds a decade into the operation. The U.S. Fish Commission, now under the new leadership of Colonel Marshall McDonald, took pride in the successful effort to replenish American waters with fish. The Star (of course) was an eager cheerleader:

“Already the progeny of the original sixty-five finny pilgrims from the fatherland have become so numerous, through the fish commission, that carp is today—though unknown to America fourteen years ago—one of the most common and widely distributed fishes of the United States. There is, in fact, not a county in any state in the union that has not carp, and it is estimated that its introduction has added $1,000,000 annually to our national food supply.”[27]

The carp’s omnipresence in America’s rivers and streams proved lucrative and was widely celebrated, but as bureaucrats patted themselves on the back, an unfortunate truth lurked beneath the waters’ surface. In the early 1890s, scientists discovered that native fish species were in sharp decline, even from the diminished levels seen 20 years earlier.[28] Since the carp in those same waters seemed to be thriving, officials were forced to consider some painful questions: Was it possible that the very fish they had so carefully cultivated as the answer to America’s fish problem had actually made the situation worse? Had carp spent the last decade destroying native populations in every pond, lake, stream, and river to which they were introduced?[29]

There was strong evidence that the answer was yes. Carp are bottom feeders, known to scavenge the floors of their habitats for vegetation. But it was not in sucking up the nests of their fishy friends that carp influenced native fish populations. Rather, when carp uprooted plants, they muddied their watery homes. The excess of muck didn’t bother the carp, but it compromised native species’ ability to feed.[30] After all, if you can’t see, you can't eat, and if you can’t eat…

In short order, public perception of the transplants changed dramatically. (The fact that American-raised carp were deemed less tasty than their German counterparts didn’t help the carp’s case, either.) In 1896, Fish Commissioner John J. Brice declared war:

“We do not propose to introduce fish in a stream without a full investigation as to its characteristics and the effect it will have on the natural denizens of such waters…The carp is a natural scavenger, and he destroys the spawn of a fish wherever he can find it. The carp follows the schools to their spawning beds and sucks up nest after nest without fear of interruption, because he is too big and wieldy for the fish he pursues to drive him away. There will be no more carp distributed by the fish commission while I am in charge of it, and they will be cleaned out of all the ponds wherever they may be that come under the authority of this office.”[31]

The criminalization of carp became a main beat for news outlets still willing to cover the apparently corrupt creatures (including the Star, though we suspect they did so reluctantly). The general sentiment was this: carp should be sleeping with the fishes.

Initiatives began immediately on a national scale to control the gilled invaders. Initially, efforts were less aggressive, with fishermen killing any carp they caught.[32] But as the bottom feeders survived this more passive strategy, mass extermination began and continued through the turn of the century. In California, seals were captured from coastlines and placed in carp-filled lakes to feed.[33] In Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, where waters were “almost boiling as the big, repulsive fish lolled about like a lot of overfat hogs,” extreme measures were taken: entire lakes were screened with nets, and any captured carp—up to twenty tons in a single lake[34]—were destroyed.[35] Across the country, bodies of water were completely drained to kill the fish that were thought to turn mud puddles into gold mines just two decades prior.[36]

In 1901, as the anti-carp campaign raged, the government ponds that remained in the District were strictly devoted to the propagation of bass and crappie for stocking the Potomac River.[37]Over the next six years, operations of the U.S. Fish Commission on the National Mall were slowly abandoned. The Eden that once flourished in the shadow of the Washington Monument, regarded as “the most beautiful picture of adorned nature in the District of Columbia” and “one of the prettiest of the capital’s parks,” became a ruin.[38] As the Evening Star lamented in 1907, “The place is the resort of tramp dogs and stray felines. The pretty buildings are empty, and the grounds vacated, except by gaunt gray herons, kingfishers, and other birds that prey upon fishes. One of the ponds is still stocked with goldfish, but there is evidence of neglect on all sides. Several of the golden fishes floated on the surface of the pond dead."[39]

By 1908, all of the fish ponds around the Washington Monument were filled in or repurposed.[40]The carp were out of sight in the District, but the notorious nuisances lived on in infamy. As one particularly resentful reporter for the Washington Post put it: “The carp are still with us. They are scattered over the entire country, and have done more damage to the fisheries than has been done even by the sewerage of cities.”[41]

That sort of hyperbole would make a great place for us to leave this fish tale, but there’s one last twist to the D.C. carp case: The Post and the majority of the American public were misinformed.

While the carp did cloud and crowd the waters of their native counterparts (especially in small lakes and fisheries), most native species were accidentally poisoned to death by the public.[42] In the late 19th century, the real culprit was pollution, which humans were pumping into every pond, lake, stream, and river that the bowels of their newly industrial cities could reach.[43] Through land mismanagement and the expulsion of waste into bodies of fresh water nationwide, it was man, not carp, who caused native fish populations to plummet.[44] But in an era when the impacts of pollution were not fully understood or appreciated, the carp became a scapegoat—pinned with the crime because they were more tolerant of contaminated water and, thus, able to survive as natives’ numbers sank.

All these years later, we can say this: They might be hideous fish that taste like mud,[45] but carp certainly aren’t the worst thing to come out of Washington, D.C. in the past 140 years.

Footnotes

- ^ “Cultivating Fish: Results of the New Hatching Process,” The Washington Post, May 10, 1880, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “About the “Smithsonian.” The U.S. Fish Commission,” The Evening Star, December 22, 1877, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ John Kelly, “The world according to carp: Answer man visits the fish ponds on the Mall,” Washington Post, November 18, 2017, https://wapo.st/2DZxXfK.

- ^ “About the “Smithsonian.” The U.S. Fish Commission,” The Evening Star, December 22, 1877, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Government Fish Ponds, Important Work of the Fish Commission.” The Evening Star, May 3, 1879, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Fish that Are Raised By Hand: The Carp Ponds Near the Monument and Their Finny Occupants,” The Evening Star, January 4, 1890, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “The Government Fish Ponds, Important Work of the Fish Commission.” The Evening Star, May 3, 1879, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “Carp Culture, an Interesting Operation—One Hundred Thousand Young Fish Removed” The Evening Star, November 17, 1880, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “The Government Fish Ponds, Important Work of the Fish Commission.” The Evening Star, May 3, 1879, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “Cultivating Fish: Results of the New Hatching Process,” The Washington Post, May 10, 1880, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Carp Culture, an Interesting Operation—One Hundred Thousand Young Fish Removed” The Evening Star, November 17, 1880, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Carp Ponds,” The Evening Star, June 25, 1881, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Danger from the Lake: Why Col. Casey wants the Carp Pond Filled Up,” The Evening Star, February 21, 1885, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Bits of Local News,” The Washington Post, January 19, 1887, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Washington Post.

- ^ E. Kurtz Johnson, and A. Hoen & Co., “Birdseye view of the National Capital, including the site of the proposed World's Exposition of and Permanent Exposition of the Three Americas.” [Washington, D.C,, 1888] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/80694601/.

- ^ “Fish that Are Raised By Hand: The Carp Ponds Near the Monument and Their Finny Occupants,” The Evening Star, January 4, 1890, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Some Big News about Fish,” The Evening Star, January 11, 1890, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “A Friend of Fish,” The Evening Star, April 4, 1896, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “History of Common Carp in North America,” National Park Service, September 18, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/nature/carphist.htm.

- ^ “A Friend of Fish,” The Evening Star, April 4, 1896, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “The Bass are Biting,” The Evening Star, April 7, 1897, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “Getting Ride of Carp,” The Washington Post, December 11, 1986, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Exterminating German Carp,” The Evening Star, November 12, 1904, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Will H. Dilg, “The Call of the Outdoors,” The Evening Star, December 25, 1924, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “Getting Ride of Carp,” The Washington Post, December 11, 1986, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Fish Commission Change,” The Evening Star, March 11, 1901, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ “Government Fish Ponds Will Be Abandoned,” The Evening Star, March 30, 1907, DC Public Library: The Evening Star.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “A War of Extermination,” The Washington Post, May 30, 1927, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “History of Common Carp in North America,” National Park Service, September 18, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/nature/carphist.htm.

- ^ Rob Buffler and Tom Dickson, Fishing For Buffalo: A Guide to the Pursuit and Cuisine of Carp, Suckers, Eelpout, Gar, and Other Rough Fish, (Minneapolis: First University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 74.

- ^ “History of Common Carp in North America,” National Park Service, September 18, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/nature/carphist.htm.

- ^ Rob Buffler and Tom Dickson, Fishing For Buffalo: A Guide to the Pursuit and Cuisine of Carp, Suckers, Eelpout, Gar, and Other Rough Fish, (Minneapolis: First University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 74.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)