The Bizarre Adolescence of the Washington Monument

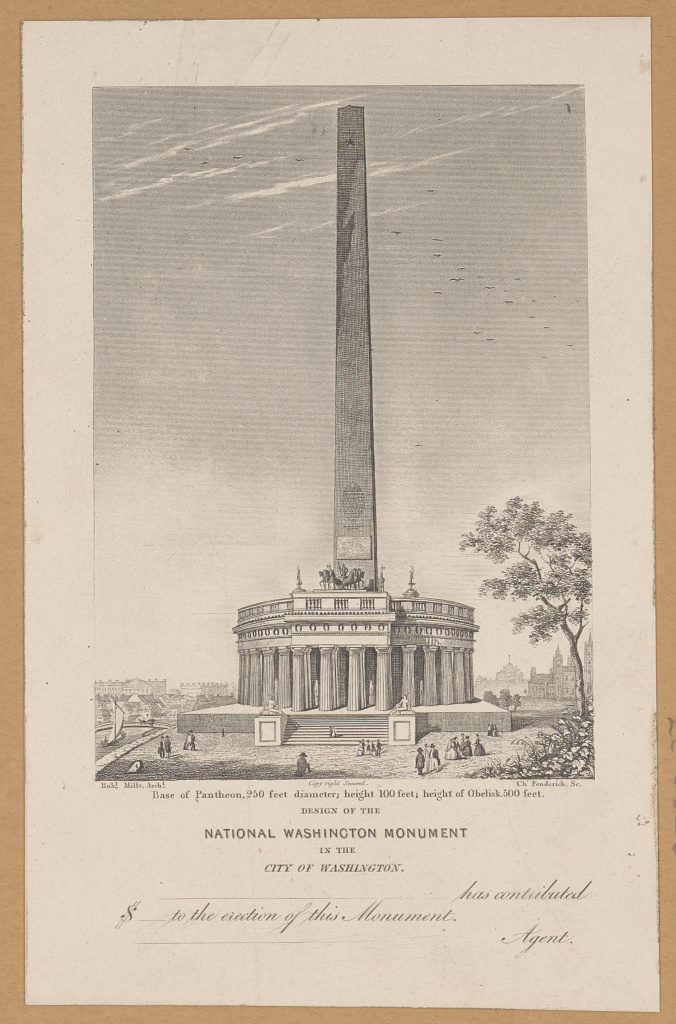

pantheon, and statues. [Source: Library of Congress]

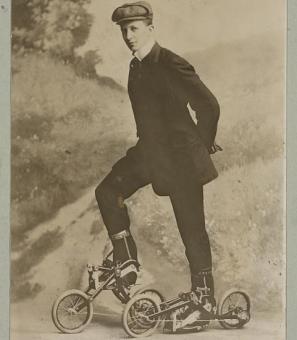

Yes, the Washington Monument had its awkward teenager phase, too. Today, the white, unmarked obelisk rising 555 feet over the National Mall is synonymous with Washington—the city and the man. But it had quite a rough and uncertain time coming to that charming simplicity. Had just a few things changed, we might well have ended up with a monument that looked very, very different.

We might have even gotten a National Sphinx.

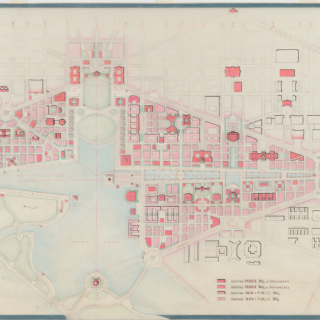

Construction of a monument to George Washington in DC was first bankrolled in the 1840s by a private group named the Washington National Monument Society. After a public architectural competition, Robert Mills’ design was selected: an intensely Classical 500-foot obelisk towering over a colonnade teeming with inscription and ornament. However, money troubles, political spats, and the Civil War paralyzed work for more than two decades.

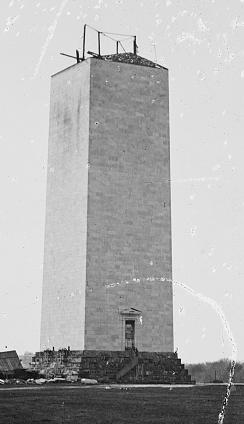

for Washingtonians. [Source: Library of Congress]

Throughout the 1860s the National Mall’s profile was defined by a stubby tower with scaffolding still poking out of the top. During the Civil War, its surrounding grounds were used to corral and slaughter cattle, leading it to be better known as the Beef Depot Monument than for its namesake.1 By the 1870s, the Washington Monument was little more than a deteriorating stump. Mark Twain called it a “a factory chimney with the top broken off.”2

No doubt the Society was disappointed, and Washingtonians weren’t too pleased with the stalled project, either: on DC’s front lawn stood a 150-foot marble “grave of buried American patriotism.”3 Finally, Congress stepped in, giving the cash-strapped Monument Society an ultimatum: the government would appropriate funds, but the Society would rescind ownership of the monument and the Army Corps of Engineers would take over construction. In protest, the Society made one last drive for donations but came up pitifully short of their goal.4 Grudgingly, they acquiesced to a Joint Committee, where the Society would have no rights but continue to “solicit funds” and act in the capacity of an “adviser.”5

Now with money, the question became not when the monument would be finished, but how. On one hand, engineers found serious problems with the foundation and ruled out building the monument to its full height.6 The second issue was Mills’ original design: it would be far too expensive and time consuming. Besides, its classically inspired architecture had fallen distastefully out of fashion with emotive Victorian sensibilities. The compromise was that the government would pay for reinforcing the foundation, and the Joint Committee would consider new ideas for construction upwards. In 1877, the Monument Society very quietly began accepting fresh proposals.

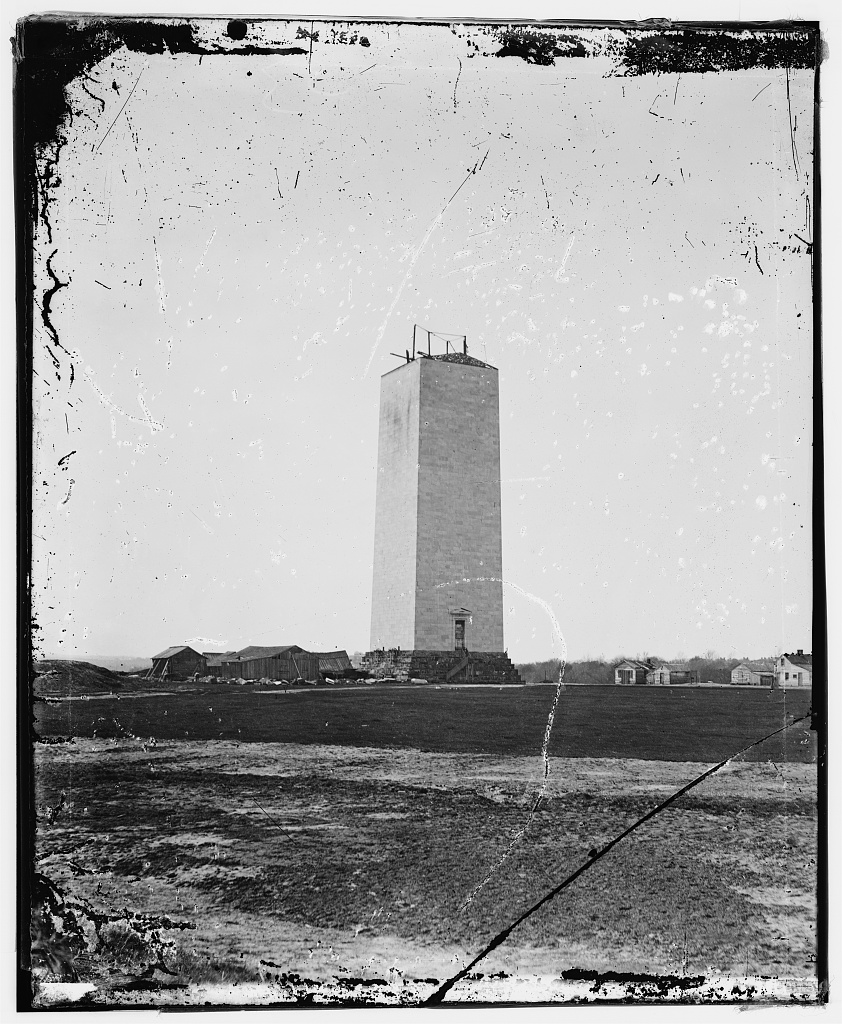

Washington. [Source: National Archives]

Accidentally, this opened the floodgates to a contentious issue for late nineteenth-century America: the expression of a national style. The Washington Monument was going to be a permanent symbol of the nation, and perhaps predictably, no one could quite agree on what that essence was, leading to a spectacular array of architectural trends all reflecting their own version of America's self-image. 7

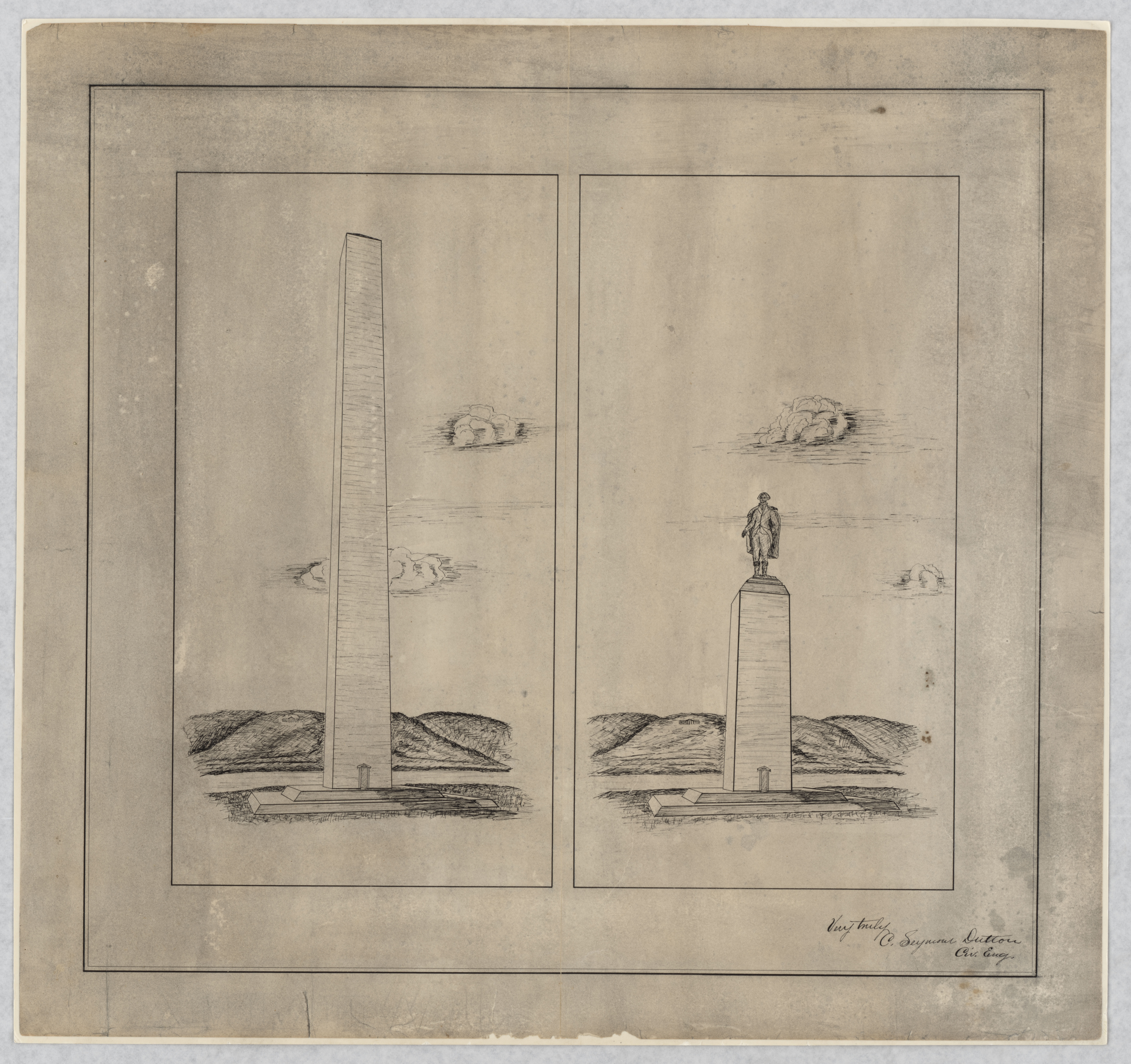

Many designs incorporated the unfinished base by simply capping it with a statue of Washington—the magnitude of which was up to the architect’s whims. Paul Schulze, designer of the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building, submitted plans to this effect. C. Seymour Dutton had a similar idea where a third of the monument would have been taken up by a large statue of the president.

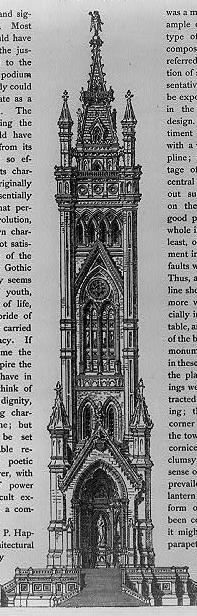

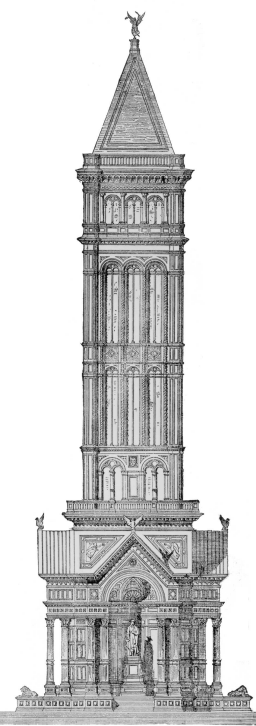

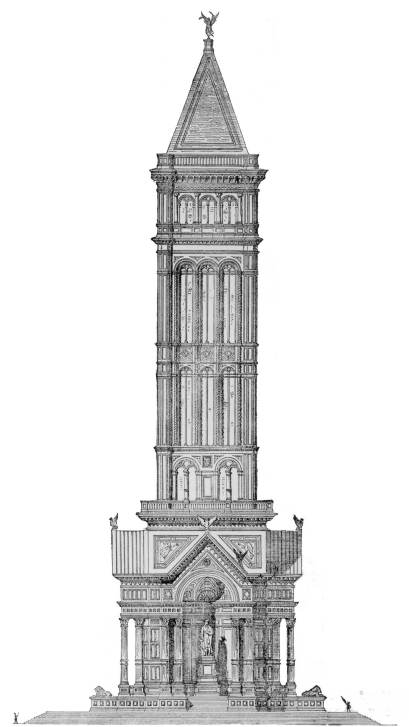

All the way from Boston, an architecture student named M. P. Hapgood submitted a design that incorporated the existing base, transforming it upwards into a gorgeously intricate tower in a medieval Gothic style. Most of the designs received in 1877 were towers, whether of Gothic, medieval, or Italianesque inspiration.8 Curiously, no one submitted any overtly Classical proposals.

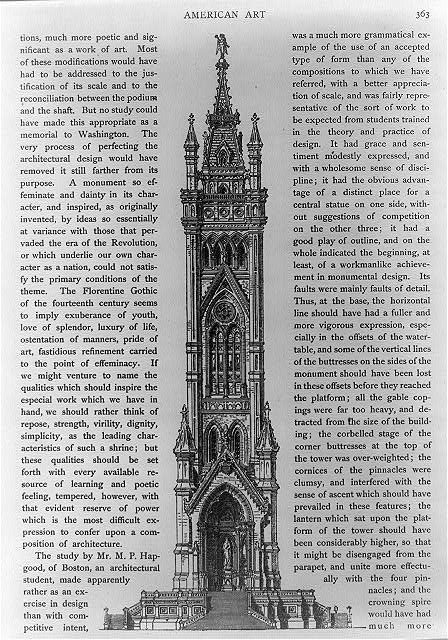

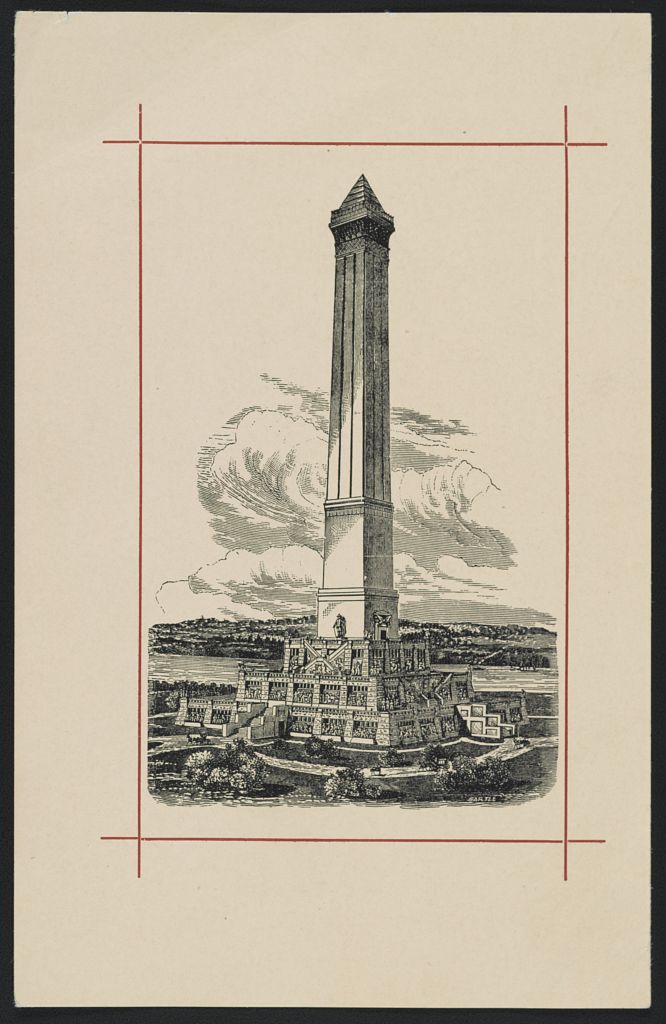

One standout in terms of style was H.R. Searle's proposal. Taking inspiration from Egyptian and Mayan architecture, featuring an obelisk atop a square three-step pyramid nearly 80 feet high. The structure came ornamented with buttresses, arches, and columns supporting nearly 100,000 feet of room for “tablets, bronzes, cenotaphs, busts” on which “the history of the past and future could be written, painted, and sculptured.”9 Of course, this design was often criticized for the wild discrepancy in style and ornamentation between the top and bottom halves, as the press and Commission’s expectation was something “characteristically American throughout.”10

[Source: Library of Congress]

elements of a Mesoamerican step pyramid and an

Egyptian obelisk. [Source: Library of Congress]

Of all the unrealized designs, perhaps most tragic was America’s missed opportunity for a National Sphinx. Part of a design by J. Goldsborough Bruff, this obelisk (much shorter than our current one) would have included unique designs for each face, topped by a triumphal arch and a statue of Washington. Around the monument were not one but four granite sphinxes. Each would have been inscribed: “An emblem of keen, far-sightedness, energy, strength, valor, and immortality.”11 To give the Egyptian style a suitably American twist, each one would have had an eagle’s head and medallions of American icons, like George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette.12

most support. [Source: NPS]

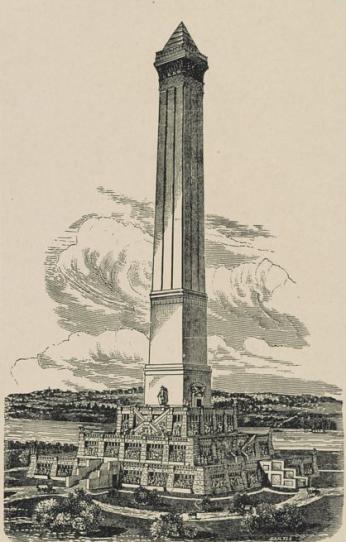

The most promising design, however, came from William Story, an expatriate living in Italy. He had a curious response to the problem of a “national style” for the monument: ‘American’ architecture, he argued, simply did not exist.13 As such, he drew from the cultural heritage of Italian republics, submitting a Renaissance tower with a statue of Washington looking down from the arched entrance. The Italianesque design quickly gained the affection of the press and public. Story also won the support of the Joint Commission’s head, William Corcoran (one of the biggest patrons of the arts in DC), securing his primacy among the candidates.

But we know that neither Story nor any other candidate would see their ambitious visions realized. Instead, the Washington monument grew into a silent, minimalist structure: a “triumph of modern abstraction” at the height of Victorian obsession with elaborate and emotional decoration.14 If these fantastical candidates didn’t properly reflect American progress and character—embodying that elusive “national style”—what about an undecorated white obelisk did?

Enter Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Casey, the man tapped by the Army Corps of Engineers to manage the monument’s construction. Professional and no-nonsense, Casey was in no mood to deal with the still-serious foundation issues and histrionics either from politicians or artists.15 Political infighting had plagued the development of the biggest public monument in the nation’s history nearly from the start. Casey’s tactic in response? Politely ignore all of it.

Aesthetics were a deadly battle as everyone searched for something that could evoke Washington, America, its history, ideals, and future. As newspapers and artists bickered over the structure’s character and visual unity, Casey sidestepped the problem of style entirely by treating the monument as a technical project, not an aesthetic one. He quietly buried his own changes to its surface, proportions, and crown under dense terminology in his reports to the Joint Commission, slipping under the radar even as debates raged over scrolls and friezes.

As he did so, unified support for any other proposal—including the once-praised Story design— crumpled as politicians, artists, and journalists began again to pick favorites. The Joint Committee had “such doses of high art forcibly rammed into their craniums,” the Washington Gazette reported, “that they [were] all in a daze.”16 In Casey’s favor, they began to insist that they must build Mills’ obelisk, period, since that was the cause people had initially donated to. They were grateful for the designs, but would not be using any of them. This was not a particularly popular decision (an incensed Story wrote to the Evening Star calling obelisks “the refuge of incompetency in architecture”) but the Joint Committee stood firm.17

Of course, Casey wasn’t immune to flashy architectural fancies either. At one point, he wanted to try a construction technique pioneered by the spectacular Crystal Palace, which had made its debut at the 1851 World’s Fair. Under this plan, the Washington Monument would have been topped by a pyramid of glass and iron. The US ambassador to Italy (who was contributing research on proper historical proportions for obelisks) quickly dissuaded Casey, telling him it would look ridiculous, and he returned to a fully stone structure.18

After forty grueling years of work, the Washington Monument was finally dedicated in 1885. Despite it being an impressive feat of engineering, the final design was hardly popular: it was plain and square, more modernist than Victorian. For a while, its only visual merit was its scale, being the tallest structure in the world—only to be surpassed by the Eiffel Tower five years later.

But perhaps all worked out for the best. The nation’s collective image of George Washington is a quiet, stern, modest president rising head and shoulders above his peers. The size and smooth stillness of the Washington Monument inspired by Mills and adapted by Casey captures that character better than any Gothic tower or Classical colonnade. As a monument, landmark, and symbol, it really can’t be improved—unless they want to put a National Sphinx back in!

[Source: National Archives]

Footnotes

- 1

Finefield, Kristi. “The Washington Monument: A Long Journey to the Top.” The Library of Congress, September 19, 2019.

- 2 Twain, Mark, and Charles Dudley Warner. The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-Day. Musson Book Company, 1874. Pp. 255

- 3

Evening Star (Washington D.C.). “Independence Day: The Fourth in Washington,” July 5, 1870.

- 4 Gordon, John Steele. Washington’s Monument: And the Fascinating History of the Obelisk. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2016. Pp. 144

- 5 Torres, Louis. “To the Immortal Name and Memory of George Washington”: The United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Construction of the Washington Monument. US Government Printing Office, 1985. Pp. 37

- 6 Torres, Louis. “To the Immortal Name and Memory of George Washington”: The United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Construction of the Washington Monument. US Government Printing Office, 1985. Pp. 39

- 7 Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. Univ of California Press, 2011 p. 121

- 8 Freeman, Robert Belmont. “Design Proposals for the Washington National Monument.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 49 (1973): 151–86.

- 9

"THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT -- MR. SEARLE'S PLAN." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 05, 1879.

- 10

"WASHINGTON'S MONUMENT.: DESIGNS FOR ITS COMPLETION. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ORIGINAL OBELISK MR. STORY'S PLAN AND ITS INCONGRUITIES-THE PLAN OF MR. SEARLE AND ITS FAULTS." New York Times (1857-1922), Mar 17, 1879.

- 11 Division, Library of Congress. Prints and Photographs. Capital Drawings: Architectural Designs for Washington, D.C., from the Library of Congress. JHU Press, 2005. Pp. 17

- 12

By Sarah, Booth Conroy. "The Best-Laid Plans in the Minds of Men: Of Monuments and Fantasies." The Washington Post (1974-), Feb 18, 1974.

- 13 Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. Univ of California Press, 2011. P. 121

- 14 Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. Univ of California Press, 2011. 107

- 15 Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. Univ of California Press, 2011. 113

- 16 Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. Univ of California Press, 2011. Pp. 125

- 17

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 28 Dec. 1878. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 18 Gordon, John Steele. Washington’s Monument: And the Fascinating History of the Obelisk. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2016. pp. 149

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)