The Long Elevator Ride to the Top of the Washington Monument

Just after 1 p.m. on Oct. 9, 1888, 32 people crammed into the Washington Monument’s newly-opened elevator[1] for a 10-minute ride to the top[2] of the world’s tallest structure.[3]

This moment was the result of 105 years of on-and-off work to construct a monument to George Washington in the nation’s capital. The process began in 1783 when the Continental Congress proposed building an equestrian statue of Washington “at the place where the residence of Congress shall be established.”[4] Pierre L’Enfant’s 1791 design for the city included a space for the monument at the intersection of the road west of the Capitol and south of the executive mansion.[5]

For roughly the next 40 years, there were intermittent discussions about ideas for the future monument, including moving Washington’s body from his tomb at Mount Vernon to a mausoleum at the capitol, but no real progress was made toward a permanent monument.[6] In 1833, Chief Justice John Marshall, former President James Madison, and other prominent leaders formed the Washington National Monument Society[7] and began raising money to fund the project.[8]

By 1836, the society raised $28,000 — about $780,000 today — and they held an open competition for monument designs. Robert Mills’ plan for a monument including a flat-topped obelisk, a statue of Washington in a chariot, and 30 statues of Revolutionary era figures was the winner.[9] But, as would become a theme of the project over the next 50 years, progress slowed due to a lack of available funds.

The society continued raising money and in 1847, they had $87,000 — about $2.7 million today — a sum deemed large enough to begin construction.[10] On July 4, 1848, 20,000 people including current President James Polk, future Presidents James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, and Washington’s adopted son George Washington Parke Custis attended the groundbreaking ceremony,[11] where a white marble cornerstone was placed.[12]

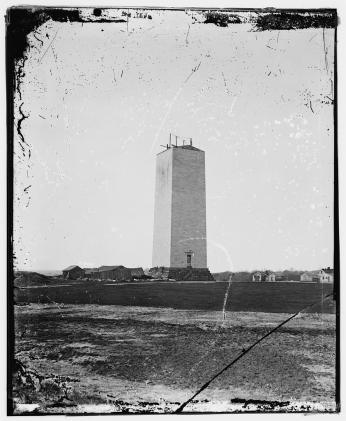

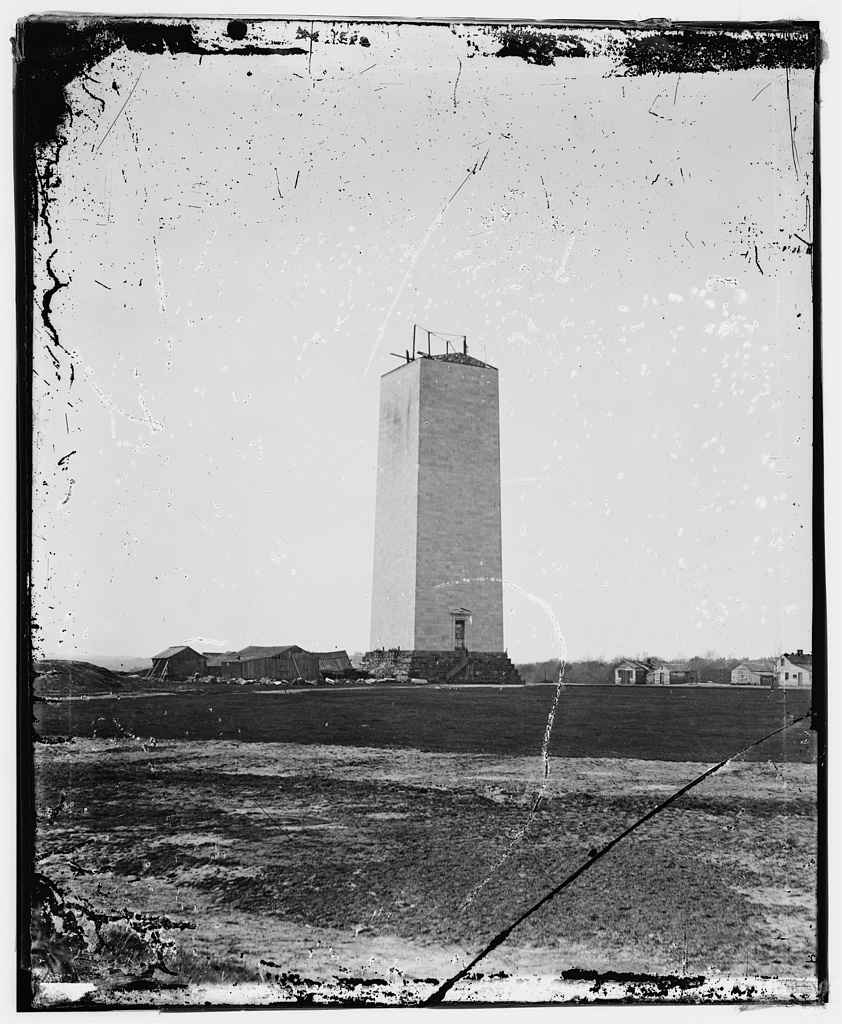

The first phase of construction ran until 1854 when a change in leadership scared donors and drove the society to bankruptcy. Mills died in 1855, and the incomplete monument sat unfinished for over 20 years — a 150 foot-tall stump on the National Mall.[13]

On July 5, 1876, Ohio Senator John Sherman introduced a concurrent resolution allowing Congress to “assume and direct completion of the Washington monument in the city of Washington, and instruct the Committees on Appropriations of the respective House to propose suitable provisions of law to carry this resolution into effect.”[14] Both houses unanimously passed the resolution, and it became law on Aug. 2, 1876. A Joint Commission formed to oversee additional work on the monument.[15]

Over the next two years, the commission determined the existing foundation wasn’t strong enough to support additional height, so they called in engineers to assess the structure and submit new construction plans. U.S. minister to Italy George Perkins Marsh studied smaller Egyptian obelisks and found that the ratio of the area of the base to the height was generally around 1:10. Given that the existing base was about 55 square feet, Marsh suggested the monument should be about 550 feet tall, instead of Mill’s original plans for a 600-foot monument.[16]

Marsh also advocated for a simple monument, saying the commission should “throw out all the gingerbread of the Mills design and keep only the obelisk.”[17]

In October 1878, the commission decided to follow Marsh’s plan and made plans to build the 555-foot obelisk we know today.[18] The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took over construction but despite trying a few different quarries, they could not find stone that was a perfect match for the blocks used in the first phase of construction. The subtle changes in color around the 150-foot mark are still visible on the monument today,[19] and are the source of one of D.C.’s most persistent myths.[20] (Despite what you may have heard, D.C. did not endure a giant flood in the 1870s, so there isn’t a water stain.)

Of course, when the Army Corps of Engineers set out to build what was then the tallest building in the world, they also had to devise a method to do so. Those stone blocks weren’t going to place themselves. To ferry the heavy stones up to the proper height, the builders installed an iron frame inside the monument. The frame had two parts: a staircase and a steam-powered elevator. The construction moved in segments of 20 feet[21] and the work was completed on Dec. 6, 1884, when workers placed a nine-inch aluminum capstone on the tip, 555 feet above the ground.[22]

Two months later, on Feb. 21, 1885 — the day before Washington’s birthday — an A-List cast of dignitaries gathered to formally dedicate the new monument.[23] After several opening speakers — and a public announcement that attendees could keep their hats on in light of the chilly temperatures — Army Corps of Engineers’ Col. Thomas Casey, stepped to the lectern and described the magnitude of the feat his team had accomplished:

“This is not the time, nor is this the occasion, to enter into the engineering details of the construction, to discuss all the strains and stresses in the several parts of the work, or the factors of safely against destructive forces. It is sufficient to say that although the dimensions of the foundation base were originally planned without due regard to the tremendous forces to be brought into play in building so large an obelisk, the resources of modern engineering science have supplied the means for the completion of the grandest monumental column ever erected in any area of the world.”[24]

President Chester A. Arthur praised the builders and accepted the obelisk on behalf of the nation.

“In the completion of this great work of patriotic endeavor there is abundant cause for national rejoicing, for while this structure shall endure it shall be to all mankind a steadfast token of the affectionate and reverent regard in which this people continue to hold the memory of Washington. Well may he ever keep the foremost place in the hearts of his countrymen ... I do now, as President of the United States and in behalf of the people, receive this monument from the hands of its builder, and declare it dedicated from this time forth to the immortal name and memory of George Washington.”[25]

As The Washington Post observed, “the speech ... eloquent and patriotic, evoked the most hearty applause” from a throng of thousands who gathered despite the cold weather. Following the program, a parade from the Monument grounds to the Capitol featured the Detroit Light Infantry, the Boston Light Guard, and the U.S. Naval Academy band.[26]

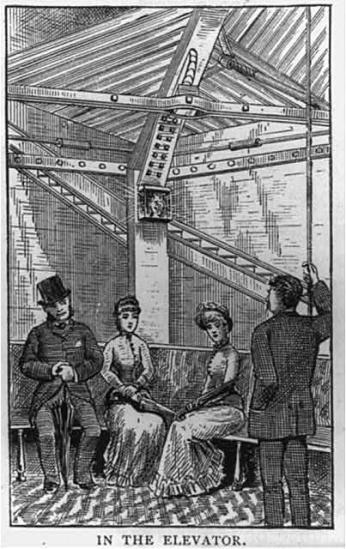

Not surprisingly, Washingtonians were eager to visit the top of the monument once the pomp and circumstance died down. Initially, the existing freight elevator was used to ferry visitors up and down, though this was only a temporary measure. (Interesting aside: elevator operator Edward Wayson told The Evening Star that in general, men seemed more scared in the elevator than women.[27]) In 1886, the 896-step[28] iron staircase opened to the public.[29] Visitors had to carry candles so they could find their way up the stairs (lights weren’t installed until January 1887),[30] and by the fall of 1886, more than 10,000 people had climbed to the top of the monument.[31]

The traffic took its toll. In the spring of 1887, the monument closed due to vandalism and The Washington Post noted “some of the damage is already beyond repair.”[32] The candles led to burn and drip marks on some of the memorial stones inside the monument and some particularly brazen visitors even took pieces of stone from the walls. The limited staff who were tasked with keeping an eye on the entire 555-foot-high structure and answering questions were unable to prevent the damage.[33]

Fortunately, efforts to improve the elevator and make it more visitor-friendly were already underway ... though, as usual, the project hit some delays due to funding.[34] Finally, in July 1888, Congress appropriated $10,500 — about $287,000 today — to care for the monument and operate an improved elevator.[35]

The grand debut of the new elevator took place on Oct. 9, 1888. At 1:16 p.m., 32 people “packed together like sardines in a box” for the maiden voyage. At the top, the visitors could see Arlington and parts of Maryland, but they didn’t stay long because it was too cold. The first group went back down, and the next 29 people took their turn in the elevator.[36]

The new elevator was an instant hit. The day after it opened, people waited in line for hours to ride to the top of the monument. On Oct. 13, The Evening Star reported that between 400 and 550 people went up in the elevator each day, with each trip taking about 30 people. The paper advised visitors to stand on one side of the elevator on the way up, and the other side on the way down so they’d have a chance to see all of the memorial stones inside the elevator shaft.[37]

Two days later, The Evening Star reported that elevator capacity increased to accommodate the demand.

“So great have been the crowds during the past few days that custodian Thomas had two benches in the car removed, in order to give more room. He discovered the necessity of this one day when the crowd inside forced the people to stand on the benches, whereby one of them was broken. Their removal gives room for fully ten more passengers. Before that, the greatest load carried was thirty-eight passengers, while on Friday afternoon on the last trip forty-seven made the ascent in the car.”[38]

The National Mall’s attractions and museums were not segregated, so all Washingtonians could visit the monument when it opened.[39]

The excitement was short-lived, however. Twice in the next two months — on Oct. 30[40] and Nov. 13, 1888[41] — the elevator briefly went out of service and had to be repaired. Despite another closure in November 1889 for additional repairs,[42] more than 50,000 people used the elevator in 1889.[43] An electric elevator replaced the steam-powered one in 1901.[44]

There have been periodic closures and outages in the decades since — including, notably in 2011 when a 5.8 magnitude earthquake damaged the monument[45] — but the modern elevator that was installed in 2019[46] is the only way for visitors ascend the monument these days because the stairs are closed to the public.[47]

Footnotes

- ^ “Making the First Trip: Thirty-Two Passengers in the Monument Elevator,” The Washington Post, October 10, 1888.

- ^ “In the Great Shaft,” The Evening Star, October 13, 1888.

- ^ Andrew Glass, “Washington Monument Completed, Dec. 6, 1884,” POLITICO, December 6, 2017, https://www.politico.com/story/2017/12/06/washington-monument-completed-dec-6-1884-277108.The Washington Monument was the world’s tallest structure for only about four years. The 1,043 foot Eiffel Tower overtook it in 1889.

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 1),” npshistory.com, November 18, 2003, http://npshistory.com/publications/wamo/history/chap1.htm.

- ^ “Washington Monument,” Nps.gov, 2011, https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc72.htm.

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 1)”

- ^ “Washington Monument”

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 1)”

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 1)”

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 1)”

- ^ “History & Culture - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service),” Nps.gov, August 26, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/wamo/learn/historyculture/index.htm.

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 1)”

- ^ “History & Culture - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service)”

- ^ U.S. Senate. (July 5, 1876). (J. Sherman, Author) [S. Res. 123 from 44 Cong., 1 sess.].

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 4),” npshistory.com, November 18, 2003, http://npshistory.com/publications/wamo/history/chap4.htm.

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 4)”

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 4)”

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 4)”

- ^ “History & Culture - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service)”

- ^ Mollie Reilly, “Washington’s Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales—Some of Which Are True | Washingtonian (DC),” Washingtonian, August 29, 2011, https://www.washingtonian.com/2011/08/29/washingtons-myths-legends-and-….

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 5),” Npshistory.com, November 18, 2013, http://npshistory.com/publications/wamo/history/chap5.htm.

- ^ “Washington Monument Construction Timeline - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service),” www.nps.gov, September 17, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/wamo/learn/historyculture/monumentconstruction.htm.

- ^ “History & Culture - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service)”

- ^ “DEDICATED: The Act Which Completes the Washington Monument,” The Washington Post, February 22, 1885.

- ^ “DEDICATED: The Act Which Completes the Washington Monument”

- ^ “DEDICATED: The Act Which Completes the Washington Monument”

- ^ “The Elevator Man,” The Evening Star, September 19, 1885.

- ^ “Washington Monument”

- ^ “Climbing up the Tall Shaft,” The Evening Star, October 28, 1886.

- ^ “The Monument Lit by Electricity,” The Washington Post, January 15, 1887.

- ^ “Climbing up the Tall Shaft”

- ^ “The Monument Closed,” The Washington Post, May 8, 1887.

- ^ “Climbing up the Tall Shaft”

- ^ “To the Monument’s Top,” The Washington Post, October 6, 1886.

- ^ “The Washington Monument,” The Evening Star, July 28, 1888.

- ^ “Making the First Trip: Thirty-Two Passengers in the Monument Elevator”

- ^ “In the Great Shaft”

- ^ “Monument Gossip,” The Evening Star, October 15, 1888.

- ^ “Histories of the National Mall | Was the Mall Ever Segregated?,” mallhistory.org, http://mallhistory.org/explorations/show/wasthemallsegregated.

- ^ “The Monument Elevator,” The Washington Post, October 30, 1888.

- ^ “The Monument Elevator,” The Evening Star, November 13, 1888.

- ^ The Evening Star, November 25, 1889.

- ^ “A History of the Washington Monument (Chapter 7),” npshistory.com, November 18, 2003, http://npshistory.com/publications/wamo/history/chap7.htm.

- ^ “History & Culture - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service)”

- ^ Michael E. Ruane, “Washington Monument Closed Indefinitely,” Washington Post, September 26, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/washington-monuments-elevator-dama….

- ^ “Guide to Visiting the Washington Monument,” Washington.org, August 22, 2018, https://washington.org/dc-guide-to/washington-monument.

- ^ “Frequently Asked Questions - Washington Monument (U.S. National Park Service),” Nps.gov, April 10, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/wamo/faqs.htm.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)