From New Columbia to the Douglass Commonwealth

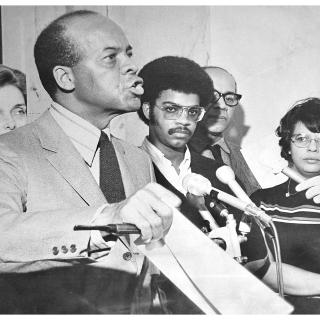

When Julius Hobson ran for the District Delegate seat under the banner of the new Statehood Party in 1971, his proposal to secure democracy in the nation’s capital was very similar to today’s H.R. 51. However, this now mainstream policy was a fringe idea for much of the past fifty years.

Following Democrat Walter Fauntroy’s victory over Hobson in the delegate race, both men continued their efforts independently; while Hobson was committed to achieving statehood, Fauntroy believed in fighting for home rule and congressional representation separately.

Although the race was over, the tension between the two dynamic District figures and their respective ideas persisted. Now a private citizen, Hobson continued his work on statehood outside of the mechanisms of elected office. He lobbied Representatives Ronald Dellums, a Democrat from California, and Fred Schwengel, a Republican from Iowa, to introduce a set of bills that would turn D.C. into the 51st state.[1]

Fauntroy blocked these measures in the House from ever coming to a vote, and when Senator George McGovern tried to introduce a similar bill in the Senate, Fauntroy threatened to turn his political network against the presidential hopeful ahead of the upcoming 1972 election.[2]

“The guy who’s holding up home rule in the District of Columbia right now is Fauntroy, not MacMillan [sic],” Hobson told the Washington Post in July 1972, correcting himself in the interview to say he meant statehood, not home rule.[2] In fact, Fauntroy blocked the initial statehood legislation because he was singularly focused on securing home rule.

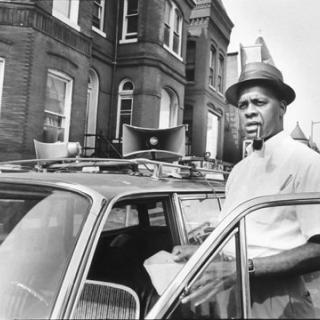

Fauntroy was a political organizer at heart, having built skills and connections through his work with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. After employing his organizing skills to defeat six other candidates for the Delegate seat, Fauntroy turned his political network toward unseating John McMillan of South Carolina, the ardent segregationist chair of the House District Committee who was the largest roadblock in Congress in the District’s path to self-governance.

He sent dozens of political organizers to McMillan’s South Carolina district to register and turn out Black voters, who made up 28% of the district, to vote for his opponent in the Democratic primary in 1972.[3] The power of the Black vote was successful in ousting McMillan from Congress.

Rep. Charles Diggs Jr, a Black Congressman from Michigan, replaced McMillan as chair of the District Committee, and Diggs and Fauntroy worked together to write the Home Rule Act of 1973. After several rounds of compromise, including regarding the management of the city’s budget, the bill passed both chambers of Congress with wide margins and was signed into law by President Nixon on December 24, 1973, giving a Christmas gift of democracy to the citizens of the District.[4]

Although the bill enjoyed large margins of support in Congress and among District residents, a small but vocal minority of white residents opposed home rule due to racial resentment towards the District’s Black majority. One member of an upper Northwest neighborhood association had testified openly about this resentment in front of the House District committee, arguing, “We just don’t want to be governed by the majority in the District of Columbia...District voters would probably take advantage of full self-government to vote themselves higher welfare payments.”[5]

This argument that Black voters would misuse their democratic power and weren’t politically capable of running the District and this willingness of some white voters to sacrifice their own enfranchisement to prevent this mishandling are pervasive themes in the chronology of District autonomy. This narrative originally played out in the first instance of Black political empowerment during Reconstruction, leading to the abolition of the District’s city government and congressional delegate seat at the time.

Conversely, Hobson also criticized home rule but instead for not going far enough in empowering the citizens of the District. He characterized the product of the congressional compromises as “Home Fool,”[6] but nevertheless, he still saw home rule as an opportunity to move his statehood efforts forward. In 1974, Hobson ran for and won an at-large seat on the new DC Council.

The 13-member council included many activists, like Hobson, but no other member was more committed to the idea of statehood than him. In 1976, Hobson introduced a bill calling for a referendum on statehood, but the council struck it down.[1] Before he could further use his new position to achieve his goal of statehood, Hobson died in 1977 from a bone cancer that had been ailing him since shortly after the Delegate race in 1971.[6]

The DC Statehood Party and the movement overall fizzled and grew quiet for several years after the death of its vociferous leader.

Meanwhile, with home rule now well-established in the District, Fauntroy pressed on with the second half of his two-part plan for District governance: full congressional representation. In 1975, Fauntroy introduced the DC Voting Rights Amendment [DC VRA], which would give the District full representation in Congress and would require that the District be treated as a state in the election of the President and Vice President and in the constitutional amendment process.[7]

After threatening to use the same organizing tactic employed against McMillan, Fauntroy gained the key support of segregationist South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond. Thurmond’s vote also brought the support of several conservative Republicans, putting the amendment just over the two-thirds threshold. Thurmond, in a speech on the Senate floor, said that “human rights begins here at home in the nation’s capital.”[8]

In 1978, the DC VRA was voted out of the House and Senate by the necessary two-thirds majorities. From there, it went to the states for the ratification process, but it met harsh pushback in state legislatures due to a conservative campaign against it. Congress had imposed an arbitrary ratification deadline for the DC VRA, and when this deadline came around in 1985, only 16 of the necessary 38 states had ratified the amendment.[8]

In late 1979, while the DC VRA was still being deliberated on by the states, Ed Guinan, a former Catholic priest and anti-poverty community activist, revived the campaign for statehood. Under a recently passed law allowing for District residents to submit referendums for voting in a general election, Guinan filed a referendum that would lead to a Congressional vote on statehood.[1]

Julius Hobson had proposed this referendum law and spoke in support of it at his last DC Council meeting, just days before his death.[9] Even posthumously, Hobson still had an impact on the fight for statehood.

Guinan’s referendum included a multiple-step process for attaining statehood, including the election of delegates to a constitutional convention, ratification of the new constitution by the voters, and finally submitting an application to Congress to become the 51st state.[1]

The grassroots referendum had little-to-no support among the political establishment, including in the waning Statehood Party, which was divided on whether to back the initiative with its dwindling resources. Fauntroy also sharply disagreed with the process, believing it would distract from DC VRA and give state legislatures a reason to vote down the amendment. Nevertheless, it passed by a 60-40 margin on Election Day in 1980.[1]

Ward 3, composed of the wealthy, predominantly white neighborhoods of upper Northwest, was the only ward in the city where the majority voted against the referendum. Only 38% of the ward voted for the initiative.[10]

In 1982, delegates gathered for the first ever District constitutional convention to debate and vote on the laws of the proposed state of New Columbia. The DC Council forced the delegation to wrap up their proceedings within 90 days, but even under this tight deadline, the convention produced a constitution with a full litany of policy, including guarantees of labor rights and gay rights. Convention President Charles Cassell described it as “the most progressive official state document...in the history of this nation.”[1]

When the new state constitution was turned over to the voters for ratification, it passed by only a slim margin of 53%. In 1983, Mayor Marion Barry submitted the constitution to Congress, and Fauntroy said it had a “snowball’s chance in July in Florida” of passing. The constitution never received a vote in either chamber.[1]

The issue of statehood slowly gained prominence over the course of the 1980s, and Fauntroy finally came to embrace the idea, introducing a version of the New Columbia Admission Act in 1987 that was voted out of the District committee for the first time. This bill also never came to a floor vote.[8]

The statehood idea also attracted the attention of Jesse Jackson Jr., a national Democratic figure who moved to the District in 1989 and ran for the newly created “Shadow Senator” position to lobby for statehood in Congress. In 1993, Jackson worked with the new District Delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton, to finally bring DC Statehood to a vote in Congress. The bill was defeated in the House with over 100 Democrats and almost all Republicans voting against it.[8]

Norton continued to push for statehood but focused primarily on other reforms to the District's status. However, in 2016, Norton and Mayor Muriel Bowser called a new convention which drafted a constitution and submitted it to the voters. In stark comparison to the lackluster support of the original constitution, the 2016 referendum passed with nearly 86% of the vote.

Shortly before the vote in November 2016, the DC Council unanimously voted to change the name of the proposed state from New Columbia to the Douglass Commonwealth.[11] The improved title is emblematic of the new chapter for the statehood struggle, one in which it has gained mainstream acceptance in the District and throughout the nation.

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d, e, f, g Musgrove, George Derek. ““Statehood is Far More Difficult”: The Struggle for D.C. Self-Determination, 1980–2017” Washington History. Vol. 29, No. 2 (Fall 2017), pp. 3-17 (15 pages)

- a, b "Fauntroy seen Stalling Home Rule." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Jul 03, 1972. https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/f….

- ^ Asch, Chris Myers, and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital [Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2017] p. 379

- ^ "NIXON SIGNS Bill ON D.C. ROME RULE" New York Times. Dec. 25, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/12/25/archives/nixon-signs-bill-on-dc-home…

- ^ Denton, Herbert H. "Home rule opposed on hill by 3 groups: 3 oppose home rule at hearing." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973) April 10, 1973. Retrieved from https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/h…

- a, b Solomon, Burt. The Washington Century: Three Families and the Shaping of the Nation's Capital. [Harper Collins: New York, 2004]

- ^ "District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment" Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/District_of_Columbia_Voting_Rights_Amendm…

- a, b, c, d Asch, Chris Myers, and George Derek Musgrove. "Democracy Deferred: Race, Politics, and D.C.’s Two-Century Struggle for Full Voting Rights" Statehood Research DC. March 2021. https://assets.website-files.com/5df7f915fcb12b538aa0494f/60541fb1af804…

- ^ Franklin, Ben. "Julius W. Hobson, a Black Activist In Washington for 20 Years, Dies" New York Times. March 25, 1977. https://www.nytimes.com/1977/03/25/archives/julius-w-hobson-a-black-act…

- ^ Schrag, Philip. Behind the scenes : the politics of a constitutional convention. [Washington: Georgetown University Press, 1985] https://archive.org/details/behindscenespoli0000schr/page/24/mode/2up

- ^ Cloherty, Megan and Moore, Jack. "DC Council settles on new name for District in statehood push" WTOP. October 18, 2016. https://wtop.com/dc/2016/10/washington-dc-statehood-name-change/

![Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.) Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/17058v.jpg?itok=egZM-IR9)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)