Remembering the American Indian Movement's Occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

“If we go, we’re going to take this building with us. If we go, this building’s not going to be here. There’s going to be a helluva smoke signal.”[1]

That’s what Russell Means, an Oglala Dakota, told Evening Star reporters on November 6, 1972, a few days after he and a group of several hundred other Native Americans broke into the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in Washington, D.C. and refused to leave.

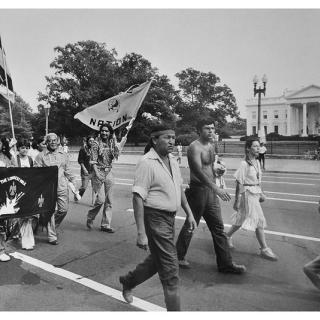

The rag tag band was made up of angry Native Americans of varying ages and genders who had traveled across the country for a march on Washington, much like the one staged by Black Americans in 1963.[2] They rallied together calling themselves the American Indian Movement (AIM). Led by Means, Dennis Banks (Leech Lake Chippewa), and Clyde Bellecourt and his brother Vernon (White Earth Ojibwe), the AIM caravan began in California and ended at the capital, picking up people along the way.[3]

Frances Wise (Waco-Caddo) of Oklahoma recalled, “A lot of people joined us. I remember driving around a freeway cloverleaf outside of Columbus, OH. All I could see were cars in front of us and behind us, their lights on, red banners flying from their antennae. It was hard to believe, really. We were that strong. We were really doing something. It was exciting and fulfilling. It’s like someone who’s been in bondage. Indian country knew that Indians were on the move.”[4]

But what was the driving purpose behind the action? According to AIM leaders:

“We seek a new American majority—a majority that is not content merely to confirm itself by superiority in numbers, but which by conscience is committed toward prevailing upon the public will in ceasing wrongs and in doing right. For our part, in words and deeds of coming days, we propose to produce a rational, reasoned manifesto for construction of an Indian future in America. If America has maintained faith with its original spirit, or may recognize it now, we should not be denied.”[5]

That manifesto came in the form of a paper known as The Twenty Points, each one outlining a demand. Among other things, the AIM argued for relief against treaty violations, land reform, and replacement of the BIA with an office that gave equal authority to the President, Congress, and individual Native nations. The main goal of the trip to the capital, dubbed the Trail of Broken Treaties, was to unite Native Americans from across the country, garner national attention, and present The Twenty Points to President Nixon.[6] Because the Nixon administration previously established a strong track record with Native Americans by returning tribal lands to Taos Pueblo and Yakima tribes and passing a bill to “resolve land claims of the Alaska natives,” the AIM expected their demands to be taken seriously.[7]

The AIM, which had begun in 1968, was unique because it framed Indigenous identity “as a way of living and viewing the world” as opposed to a racial issue. As a result, the AIM appealed to Native Americans without a “strong ethnic or cultural awareness.” Banks, Means, and the Bellecourt brothers wanted to get Natives from both cities and reservations involved in their cause, and the Trail of Broken Treaties seemed like an effective way to do just that.[8]

According to the Evening Star, around 400 protesters gathered outside the BIA on November 2, 1972 from as many as 250 tribes for a week of demonstrations and discussions (other sources reported that there were 700 or 800 people in total).[9] Over 80% came from reservation towns.[10] Although the protests were intended to be peaceful, Means suggested the group would take a more hardline approach in the future if their demands were not met. Upon arriving in Washington, he vowed that he would “give the country until 1976 when the white man will be celebrating the bicentennial. If they haven’t produced meaningful change by then, they’re not going to have a happy celebration.”[11]

Almost immediately, however, the mood of the demonstrations became tense. Before they made the journey to D.C., AIM leaders arranged for local churches to provide the protesters with food and housing for the week. Then, once the caravan got there, the churches revoked those offers for unknown reasons. While some were able to stay at a prearranged site the night of November 2, there was not enough space for everyone, so most of the demonstrators looked to the BIA for help in finding food and lodging.[12] When none came, they decided to settle inside the BIA headquarters building itself.[13]

By Suzan Harjo’s (Cheyenne and Hondulgee Moscogee) account, “It was the end of the workday for Washington bureaucrats and few BIA employees remained in the building after 4:30 p.m….[General Services Administration] police clashed with [Indigenous] people in the lobby at the very time that American Indian Movement leader Dennis J. Banks, Leech Lake Chippewa, was conducting a press conference out front. Within minutes, GSA withdrew from the building and the [Trail of Broken Treaties] was barricaded inside.”[14]

They were fed up with bureaucracy as a whole, not just the federal government. As Martha Grass, a 50-year old Ponca woman from Oklahoma, put it, “The other minorities have made progress since 1968, but not the American Indian. We just have to deal with too many bureaucrats - the Interior Department here, the counsels in our own areas, and all the rest of them – and we can’t get anything done. Other minorities don’t have this kind of bureaucratic structure to deal with.” Grass joined the Trail of Broken Treaties with several young people, some of whom were still in grade school, explaining, “I took them out of school and told them you’ll learn more up there in Washington than you ever will here.”[15]

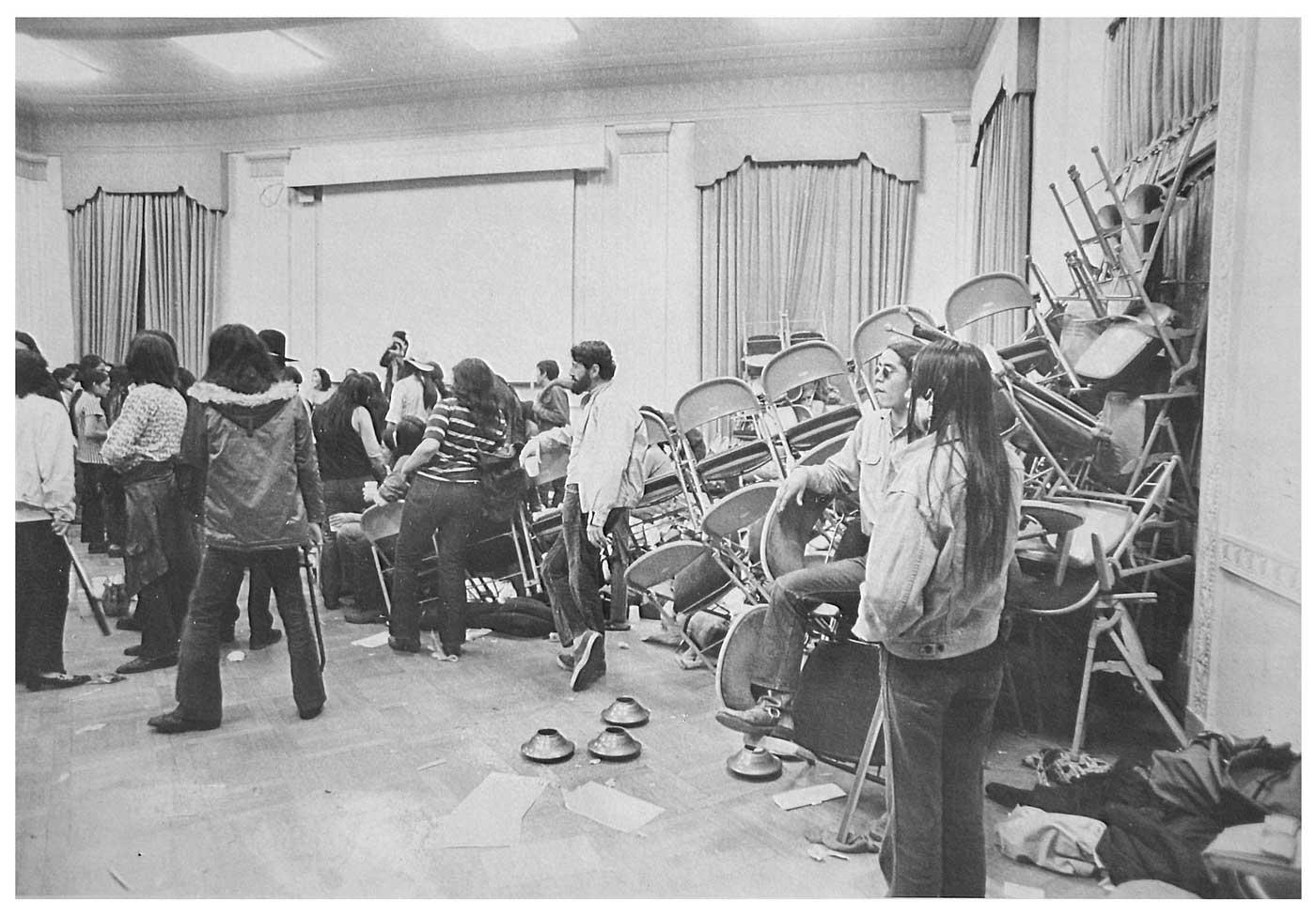

On the morning of November 6, the Department of the Interior offered “comforts” to the remaining protesters if they ended the occupation. About 100 people did leave, but the rest of the demonstrators piled furniture to block the doors, enraged after Nixon sent a letter rejecting the AIM’s multiple requests to meet with him.[16] They also began arming themselves, fashioning weapons out of steel rods, chair legs, and letter openers. The possibility of violence grew with each government request to leave the BIA.[17]

At one point, Harjo recalled seeing Means lighting a Molotov cocktail and hearing him yell, “It’s a good day to die.” But Harjo and others around her couldn’t let that happen, and together they stomped on the fuse until it was completely shredded. Oren Lyons, one of the other men there, chastised Means’ rash actions, saying, “You can’t do that. You can’t kill the people and destroy all those records. This is only a battle, not the war.”[18]

Although most of the group dispersed by November 8, around 150 protesters remained and wouldn’t budge, so the government decided it was time to hear them out by creating an interagency task force to discuss the AIM’s proposals.[19] Early on in the process, the main negotiator, Henry Adams (Assiniboine-Sioux), got a call from Democratic Representative Julia Butler Hansen of Washington. Adams observed, “Just the fact that she was calling strengthened our hand and made them pay close attention. They were impressed because she chaired the House subcommittee on Interior appropriations." He added that Hansen even remarked, “It's about time someone went in there and tore that damn place apart."[20]

Tearing the place apart is exactly what happened. In addition to breaking furniture, some of the demonstrators raided file cabinets, uncovering information related to Native American affairs that would incriminate multiple members of Congress. Rather than revealing the content of documents, Means only told the press, “What we are taking is secret. For the past 72 hours, we have been sorting through all this with our attorneys. We know what is important.”[21]

Amidst the havoc, negotiations did take place. The task force agreed to “draw up recommendations on Indian problems to be presented to President Nixon by June 1.” With that, the remaining protesters felt their mission had been accomplished. On November 9, the Evening Star reported, “The last two dozen Indian activists, who were under a court order to evacuate the building by 9 p.m. yesterday, quietly filed out at 9:15 p.m. and got in their cars. Then, escorted by two District police cruisers, the last of the “Trail of Broken Treaties” caravan headed west on Constitution Avenue and out of the city.”[22]

In the short term, the federal government gave the demonstrators money to travel home and promised not to prosecute any of them for occupying the BIA (the amnesty did not extend to the damages).[23] But over the course of the following year, The Twenty Points were pretty much discarded, because according to one administration official, “A government makes treaties with foreign nations, not its own citizens.” The AIM even came to be viewed as a threat, leading the FBI to classify the movement as an extremist organization. Furthermore, “the Nixon administration, the FBI, and local police began a deliberate widespread attempt "to discredit, isolate, and imprison AIM leaders,"” overshadowing earlier efforts to listen to the group’s complaints and suggestions.[24]

Not surprisingly, members of the movement were extremely disappointed with the government’s response to their efforts, but many continued to fight back in other ways.[25] When all was said and done, Frances Wise emphasized, "We came from Indian communities. When the flamboyant stuff was over, most of us went back home to help make our communities strong."[26]

Footnotes

- ^ “Indian Protesters Defy Eviction,” Evening Star, November 6, 1972, 1.

- ^ David Kent Calfee, “Prevailing Winds: Radical Activism and the American Indian Movement,” PhD diss., East Tennessee State University, 2002, 44.

- ^ Suzan Shown Harjo, “Trail of Broken Treaties: A 30th Anniversary Memory,” Indian Country Today, last updated September 12, 2018. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/trail-of-broken-treaties-a-30th-…;“Clyde Bellecourt,” Project Humanities, Arizona State University, accessed October 25, 2021, https://projecthumanities.asu.edu/content/clyde-bellecourt.

- ^ Alvin M. Josephy, et al., Red Power: The American Indians’ Fight for Freedom (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 44.

- ^ “Trail of Broken Treaties 20-Point Position Paper,” American Indian Movement, accessed October 18, 2021, http://www.aimovement.org/archives/index.html.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Deloria, Behind The Trail of Broken Treaties, 61.

- ^ Jeffrey Stotik, et al., “Social Control and Movement Outcome: The Case of AIM,” Sociological Focus 27, no. 1 (February 1994): 57.

- ^ David Holmberg and Harriet Griffiths, “Indian Leader Sees Future Violence,” Evening Star, November 2, 1972, 3. Harjo, “Trail of Broken Treaties.” “The Trail of Broken Treaties: March on Washington, DC 1972,” Rising: The American Indian Movement and the Third Space of Sovereignty, Muscarelle Museum of Art, 2020. https://muscarelle.wm.edu/rising/broken-treaties/.

- ^ Vine Deloria, Jr., Behind The Trail of Broken Treaties: An Indian Declaration of Independence (Texas: University of Texas Press, 2010), 57.

- ^ Holmberg and Griffiths, “Indian Leader Sees Future Violence,” 3.

- ^ “Indian Protesters Defy Eviction,” 1.

- ^ Harjo, “Trail of Broken Treaties.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ David Holmberg, “Indians ‘Doing Their Own Thing,’” Evening Star, November 4, 1972, 7.

- ^ “Indian Protesters Defy Eviction,” 1 & 6. “The Protesting Indians: Sit-In and Negotiations Continue,” Evening Star, November 5, 1972, 61

- ^ “Indian Protesters Defy Eviction,” 1 & 6.

- ^ Harjo, “Trail of Broken Treaties.”

- ^ Donald Lott, “Indian Cadre Remains in BIA Building,” Evening Star, November 8, 1972, 8.

- ^ Harjo, “Trail of Broken Treaties.”

- ^ Lance Gay, “Indians Go With ‘Incriminating’ Files,” Evening Star, November 9, 1972, 23.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Mitchell Satchell and Toni House, “Indians Held Liable: BIA Damage Hits $1.9 Million,” Evening Star, November 10, 1972, 1.

- ^ Stotik, et al., “Social Control and Movement Outcome,” 59.

- ^ Deloria, Behind The Trail of Broken Treaties, 61.

- ^ Harjo, “Trail of Broken Treaties.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)