The Action-Packed History of the Declaration of Independence

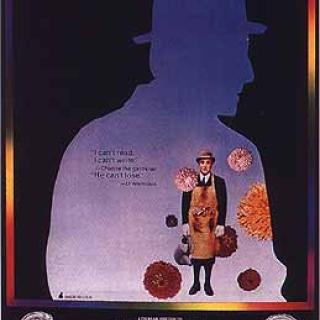

Washington, D.C. has been the backdrop for a number of films and TV shows throughout its history. But, at least in my lifetime, one movie just about everyone has seen is National Treasure. Known for its adventure-packed plot and witty characters, the film starring Nicolas Cage, Diane Kruger, and Justin Bartha, among others, has turned certain D.C. spots into places ripe with niche movie references, especially about the Declaration of Independence.[1] One Instagram account has even dedicated itself to everything National Treasure-meme related (@national_treasure_memes, for anyone wondering!).

In case you’ve forgotten the story, or haven’t seen it (no judgement!), here’s the general idea: main character Benjamin Franklin Gates is searching for a legendary treasure that his family has chased for generations. Ben and his tech-genius sidekick Riley Poole team up with questionable character Ian Howe and his crew to find the treasure and soon discover a clue leading to the Declaration of Independence. When it becomes apparent that Ian plans to heist the document, Ben determines there’s only one solution to keep the Declaration safe: he and Riley have to steal it first – and find the clue it holds for their treasure hunt.[2]

Seems pretty simple, right? According to Riley, not at all. Sitting in the Library of Congress, Riley tells Ben that in addition to a bulletproof, sensor-riddled case, they have to contend with security cameras, guards and “kids on their eighth-grade field trip” if he plans to steal it while on display.[3] If Ben wants to try to take it when it's not on-display, then he’d have to find a way to get through “a four-foot-thick concrete, steel-plated vault also equipped with an electronic combination lock and biometric access denial systems.”[4] In short, it’s impossible.

Of course, in his main-character fashion, Ben has a plan. They’ll nab the Declaration during maintenance work, where the only thing protecting it is the case. Easy, peasy. Well, not exactly… and the action is enough to fill two and half hours, full of twists and turns.

Obviously, the Declaration has great value to the history of the United States, but, perhaps more surprising than Ben and Riley’s plan to steal the Declaration is the fact that it was still around for them to nab when the movie came out in 2004. Indeed, the Declaration’s real-life 200+ year journey from its creation in 1776 to its current display in the National Archives Rotunda gives the plot of National Treasure quite the run for its money. The document has traveled many miles and withstood multiple threats – including some misguided preservation attempts that would make present day archivists shudder. Let’s take a look!

Next Time, Don’t Skimp on the Ink

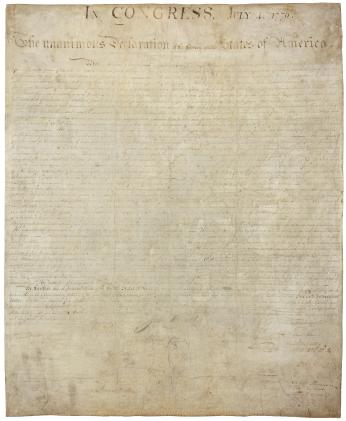

It’s 1776, and the Founding Fathers just wrote the Declaration of Independence. While they were responsible for the document’s writing, they weren’t the ones who actually put the pen to the paper of the document we know today; they simply signed it. The man responsible for actually writing the Declaration on its official paper was Timothy Matlack. National Treasure, for the most part, got this part right: “Fifty five in iron pen/Mr. Matlack can’t offend.”[5]

Timothy Matlack, per Ben, was the scribe for the Continental Congress at the time of its creation, and “iron pen” refers to the type of ink Matlack used to write the original Declaration called iron gall ink. It was “inexpensive and readily available,” and was in fact commonly used for centuries worldwide.[6] The ‘fifty five” then refers to the number of men who signed the Declaration at the time of writing.[7]

While all of that’s interesting (thanks, Ben!), how does iron gall ink hold up almost 250 years later? Not too well. According to experts, the make-up of iron gall ink (a mixture of tannin, vitriol, gum Arabic, and water) makes it easy to make and use when writing, but as time goes on, fades gradually into a brown color and even disappears if not preserved correctly.[8]

This is exactly what happened to the Declaration of Independence – the ink faded naturally, and, if you’ve seen the Declaration recently, even someone with perfect vision would have trouble deciphering it (aside from the fact that it’s written in 18th century cursive). It’s definitely a lighter shade of brown than its original black. For this reason, it might be even more impressive that Ben is even able to read from the Declaration before they steal it.

The Revolutionary Road Show

So, the ink used to write the Declaration’s natural fading made preservation necessary, but what about the physical document? Unfortunately, it has been through the historical wringer too.

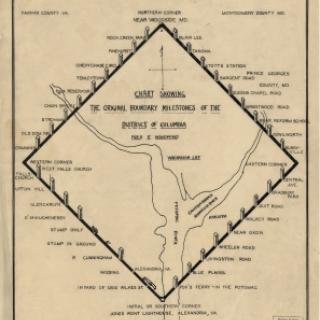

After Timothy Matlack created the large parchment document and the Revolutionary War began, the need to protect the original was essential. Because keeping it safe was more pressing than keeping it pristine, this resulted in it being rolled, folded and concealed in a number of ways. The Declaration travelled with Congress throughout the war and, based on the best estimates from the National Archives, would’ve spent various amounts of time in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.[9]

After the successful creation of the Union, the document stayed with Congress in Philadelphia for a number of years before Washington, D.C. became the seat of government in 1800. Congress moving to D.C. meant that the Declaration would naturally follow. Having had its fair share of touring the fledgling country, going to the new capital would finally let the Declaration rest.

Not really.

While D.C. has been the Declaration’s home since 1814, the document still did a lot of moving around, and some of its many homes in the District did a better job than others in keeping it safe. From 1814-1841, it was housed in three different State Department records building, the final one having “no security against fire.” Yikes.[10]

Copperplating: The Best of Intentions

Around 1820, concerns about safety and a push for preservation created a need to make copies of the Declaration, which had been done previously, but not on a large scale. Then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams undertook a project to create copies of the Declaration for wider circulation, as well as minimizing exposure of the original.[11] But, while we have access to photography, copiers, and other technology now, the solution available to Adams was to make copies right from the original.

This process – copperplating – involved pressing damp fabric against the document and transferring some of the existing ink to a transfer plate, creating the copies from there.[12] This wasn’t ideal for a few reasons: the ink, as we’ve learned, was cheaply made, and therefore less suitable for this process; also, the parchment itself had already been folded and worn down during the Revolutionary War, which had already compromised its integrity. Safe to say, while Adams and those involved in the project had good intentions, the process didn’t help to preserve the original, as much as the copies made sure more existed. Copies in-hand, the original Declaration was then relegated to display.

It’s a Sunshine Day

In 1841, the Declaration found a home in the Patent Office (present day Smithsonian Portrait Gallery). While the building was constructed to be fireproof (a great step forward in theory – more on that later!), the display of the Declaration was… less than ideal. It hung on a wall facing a window, exposing it to direct sunlight and humidity for 35 years. Its position in the building and lack of substantial protection against the elements caused the ink to fade even more.

Visitors to the Declaration that had the chance to see it were not impressed, even making fun of its appearance out of concern. One writer in 1856 off-handedly called the Declaration “that old looking paper with the fading ink."[13] Throughout the 1800s, calls to restore and preserve the original document were made by newspapers and government officials alike.

100 Years Later: Centennial Concerns

Concerns about the Declaration’s condition escalated even further with the pending centennial in 1876, which included plans to display the document in Philadelphia. After spending time in the city where it’d been written, major conversations about preservation came to a head. Congress event adopted a joint resolution providing "that a commission, consisting of the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and the Librarian of Congress be empowered to have resort to such means as will most effectually restore the writing of the original manuscript of the Declaration of Independence, with the signatures appended thereto."[14] But again, little action was taken. Committees charged with examining the Declaration’s condition noted its degradation, but had no serious recommendations for the future.

Fortunately, the State Department did take one action in 1877 that proved prescient, by moving the Declaration to a new fireproof building shared by the State Department, War Department and Navy Departments. And it was just in the nick of time. A few months after the move, the Patent Office – you know, the supposedly fireproof building where the Declaration used to live – caught fire. Though catastrophe had been avoided, the spot chosen in the new digs wasn’t perfect: smoking was still legal indoors, and the room held a usable fireplace. After 17 years of display in the new building, a new committee tasked with examining the Declaration suggested a custody transfer to the Library of Congress to ensure the best care possible. It would take a few years to officiate the change, but the Declaration would soon be on the move yet again.[15]

A New Home in the World’s Largest Library

When President Harding was considering the executive order that would grant the custody change, Secretary of State Charles Evan Hughes assured him that the documents “[would] be in the custody of experts skilled in archival preservation, in a building of modern fireproof construction, where they can safely be exhibited to the many visitors who now desire to see them.”[16]

Harding signed the executive order and on September 30, 1921, the documents were brought to the Library, which was celebrated as “a more suitable place” for their exhibition and preservation.[17] In the next three years, the Library of Congress would build what many called a ‘shrine’ to the three documents for their display and protection. When the case was finally ready on February 28, 1924, the dedication ceremony to their permanent display commenced, with President Coolidge, members of Congress, and numerous political figures coming to celebrate the founding documents.[18]

Not Your Mother’s Preservation Methods

While the venue change was undoubtedly an improvement, preservation methods during the early 20th century left something to be desired – and the Declaration suffered because of it. As Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler, the Archives retired chief of conservation, and Catherine Nicholson, the Archives’ retired chief of conservation wrote in the fall 2016 issue of Prologue, the National Archives quarterly magazine, “The defining damage that made the Declaration what it is today was not the result of 19th-century copying or excessive exhibition, but occurred in the 20th century.”[19]

The most prominent defacement is a smudged handprint that “someone may have tried to rub out” on the bottom left corner. It was originally blamed on a 19th century mistake, but photographs prove it occurred after 1903 (photographs in 1903 show no handprint, but one in 1940 does).[20] Unfortunately for preservationists, in addition to the handprint, another (or perhaps the same) person also took the fading ink situation into their own hands.

Someone who had access to the document attempted to re-trace Timothy Matlack’s original script to darken it. Exactly when this happened – or why it was permitted to happen – is a mystery. While the re-writing is not as visible as the handprint, experts say that in the present day, major changes such as these would be considered defacement and would never be conducted. Phew.[21]

Under Lock and Key

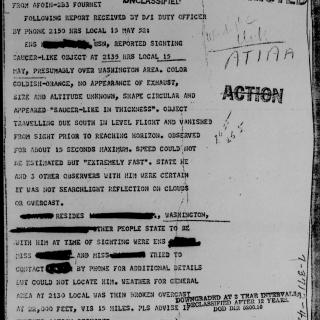

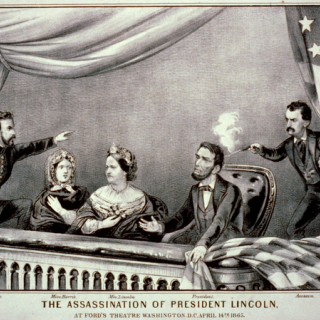

Although these defacements were concerning during the 1940s, the United States had much bigger concerns with the abrupt entrance into World War II due to the attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 23rd, the Declaration, Constitution, and other important documents were escorted to various safe locations, including Fort Knox, where they would remain for the rest of the war. While the Declaration received regular maintenance, its disappearance from display was a heavy reminder of war and the threat of another domestic attack.

After three years at Fort Knox, the Library of Congress was eager to have their documents returned and the Declaration was returned to D.C. in October 1944, much to the delight of both the Library of Congress and the public.

Seems like a fitting ending to the Declaration’s journey, right? Almost. In the 1950s, the Declaration came under yet another custody battle between the National Archives and the Library of Congress.

The (Not So) Long Journey to the Archives

While the Library of Congress had cared for the Declaration for 31 years, the National Archives petitioned for custody under the Federal Records Act. When the move was approved in 1952, many at the Library felt the loss. As security guard Joseph Sloan told the Washington Post, he was “proud to have the honor of guarding them. We’re sorry to see them leave.”[22] While the Library of Congress still had the Jefferson-annotated Declaration for display, the original printing and its fellow Charters of Freedom moved down Pennsylvania Ave to the Archives.[23]

The general public celebrated the chance to see the documents’ transfer; multiple reports of the day and at the dedication ceremony had positive remarks for all the events. At precisely 11 o’clock on December 13, 1952, the processional party made its way through downtown D.C., with the Charters escorted by military-grade protection, tanks, and a color guard for the mile-long journey.[24]

President Truman’s dedication speech two days later on the 15th at the enshrinement ceremony implored that “[t]he external threat to liberty should not drive us into suppressing liberty at home,” among other statements that condemned Communism, using the Charters of Freedom as evidence of the stability of democracy, especially with their continued preservation.[25]

The End of a Wild 200-Year Journey (Hopefully!)

Since the 1952 move, millions of tourists have visited the Declaration at the National Archives Museum and by the late 1970s, the case had been equipped with more high-tech sensors and monitors to ensure its safety and stability. Perhaps the security is similar to what Riley detailed in the movie, but who really knows? As Archivist of the United States David Ferriero joked to New York Magazine, “We do have a plan, BUT I’d have to kill you if I told you.” More seriously, he said that protocols for the Charters of Freedom are top-secret to ensure their safety, even in the case of nuclear warfare.[26]

And in case you were still wondering if there’s anything hidden on the back of the Declaration as suggested in the movie, or if lemons and heat can reveal secret writing on a document, here it is straight from the National Archives themselves:

While we all love a good adventure movie and treasure hunts, I think it’s safe to say the Declaration’s had enough action since it's been written, and deserves to sit-out any future interesting history.

Footnotes

- ^ “National Treasure – Cast,” IMDB, accessed 5 April 2022. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0368891/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

- ^ National Treasure, directed by Jon Turteltaub (2004; United States: Buena Vista Pay Television, 2020), Amazon Prime Video.

- ^ “National Treasure – Impossible Heist,” YouTube, accessed 25 March 2022, TIME. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muCBy6Y4_ok

- ^ ibid.

- ^ National Treasure, directed by Jon Turteltaub (2004; United States: Buena Vista Pay Television, 2020), Amazon Prime Video.

- ^ “Iron Gall Ink – Ink of kings, monks and poets,” The Iron Gall Ink Website, accessed 8 March 2022. https://irongallink.org/iron-gall-ink-ink-of-kings-monks-and-poets.html

- ^ Some of Ben’s information is slightly off or inaccurate; while we don’t discuss these flaws here, an article from the Harvard University Declaration Resources Project does a good deep dive on what the movie got right and wrong: https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/blog/facts-nationaltreasure

- ^ “Iron Gall Ink – Ink of kings, monks and poets,” The Iron Gall Ink Website, accessed 8 March 2022. https://irongallink.org/iron-gall-ink-ink-of-kings-monks-and-poets.html; for a more in-depth look at iron gall ink’s ingredients, see this page: https://irongallink.org/iron-gall-ink-ingredients.html

- ^ Our historical timeline for the Declaration’s lifespan came from this article done by the National Archives: “The Declaration of Independence: A History,” National Archives, accessed 25 March 2022. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-history

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Joe Pappalardo, “Declaration of Independence Preservation – the Science of Saving the Declaration of Independence,” Popular Mechanics, 3 July 2020. https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/a22025447/declaration-of-in…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ “The Declaration of Independence: A History,” National Archives, accessed 25 March 2022. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-history

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ “Library of Congress To House Documents Of Nation’s Birth,“ The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 30 September 1921, https://www.proquest.com/docview/145876932/FF1F827AC7D41BFPQ/4?accounti…; All significant dates were provided by the National Archives’ official history on the Declaration of Independence as cited before.

- ^ Another article detailing the ceremony highlights the symbolic meaning of the Declaration and its counterparts, and can be found here: https://www.proquest.com/docview/149447606/fulltextPDF/715EC7FC392B42BB…

- ^ Michael E. Ruane, "Was the Declaration of Independence ’defaced’? Experts say yes." The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 21 October 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/was-the-declaration-of-independenc…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ The National Archives hasn’t missed their opportunity to tell the story of these mysterious changes – read their article here: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/fall/declaration

- ^ Library Sad at Losing Prized Documents,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 12 December 1952, https://www.proquest.com/docview/152509736/BDD248F0A9EE4B89PQ/2?accountid=46320

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Paul Campson, ”Charters of Nation’s Liberty To Move Under Tank Guard,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 7 December 1952, https://www.proquest.com/docview/152510935/BDD248F0A9EE4B89PQ/1?account…

- ^ Paul Sampson. "Hysteria Peril to Liberties, Truman Says: Truman Sees Liberty Menaced by Hysteria," The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), 16 December 1952. https://www.proquest.com/docview/152507116/fulltextPDF/BDD248F0A9EE4B89…

- ^ Dan Amira, "How the Government Would Protect the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence During a Zombie Apocalypse," Intelligencer, (New York City, New York), 25 June 2013. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2013/06/zombies-constitution-world-war-z-plan-declaration.html

>

>