Meet Frances Benjamin Johnston, "The greatest woman photographer in the world"

In 1943, The Hampton Album, an anonymous leather-bound portfolio containing platinum photographic prints of students and educators was discovered in an antique bookstore in Washington, D.C., by writer, philanthropist, and collector Lincoln Kierstein.1 The handmade album had no indication of an author.

It spent years collecting dust on Kirstein’s bookshelf, only brought out to be viewed by historians – until 1965 when Monroe Wheeler, the Director of the Publications at the Modern Museum of Art persuaded Kierstein to hand the album over to the museum.2

Grace M. Mayer, MoMA’s photography curator, took on the role of detective. The album was determined to contain images from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia (now Hampton University) around the turn of the century. Mayer traveled to Hampton to learn more. She transcribed hundreds of archival documents, and returned with “conclusive evidence” that the creator of the album was none other than trailblazing Washington, D.C. photographer Frances Benjamin Johnson.

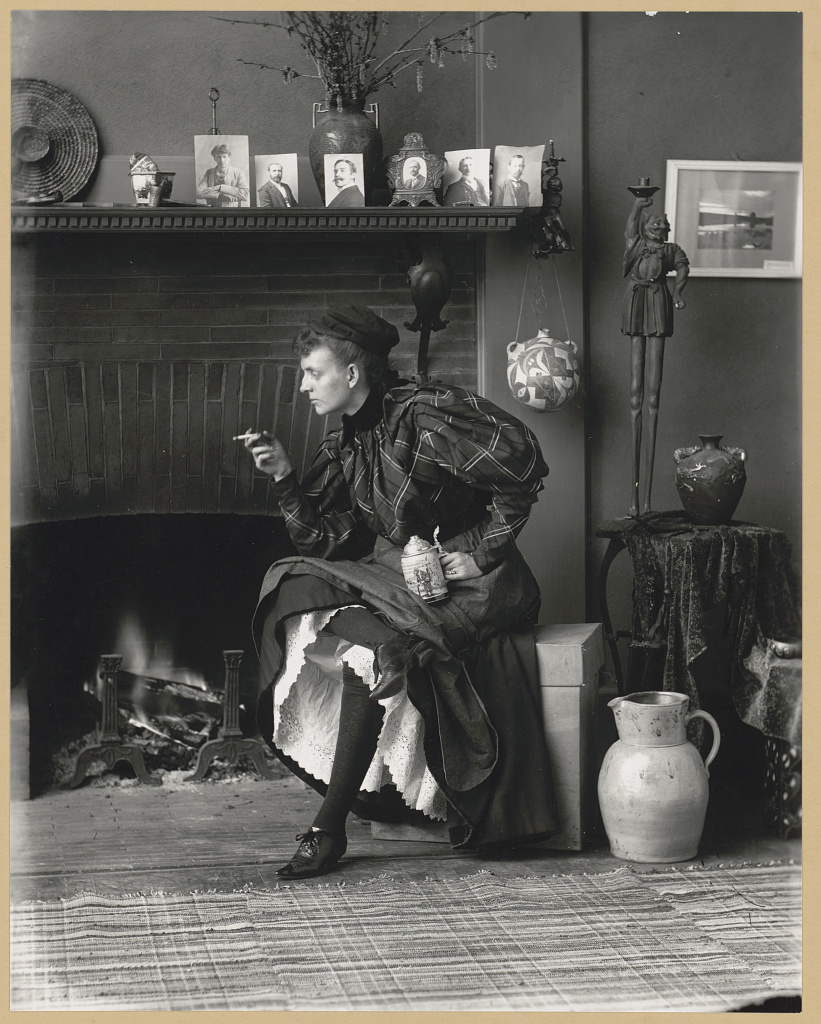

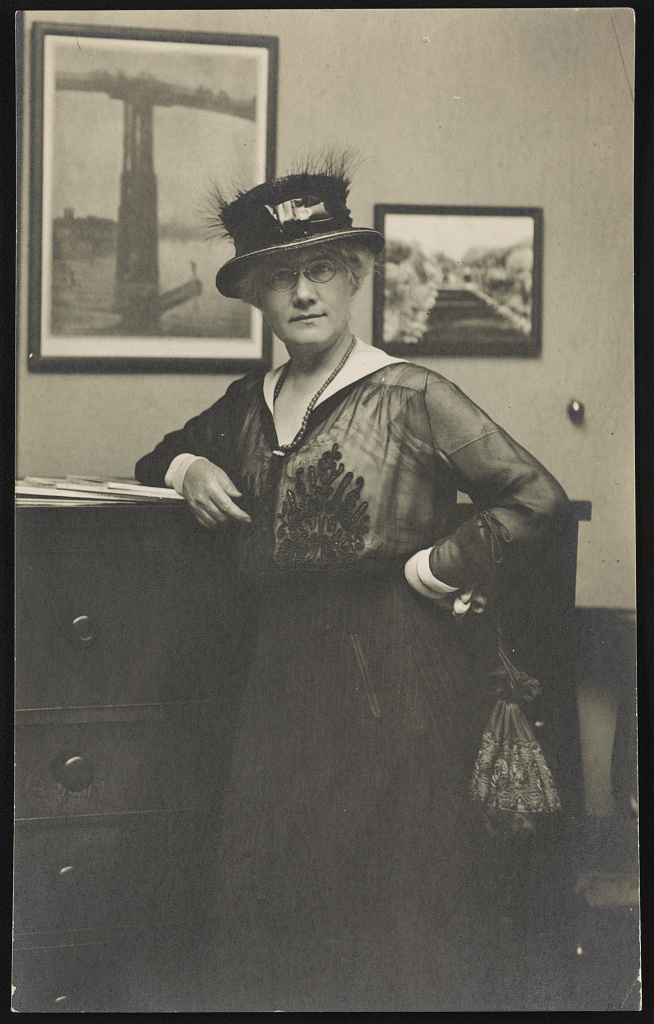

Frances Benjamin Johnston lived a life of wonders. Recognized as one of the first woman press photographers, she soared through the glass ceiling. Her life was one of mystery and slight controversy, defying gender norms, photographing racial matters, and being described as “the most famous lesbian you’ve never heard of.”3

Johnston was raised upon privilege. Her mother, Antoinette Benjamin Johnston, was one of the first woman political journalists for the Baltimore Sun and her father, Anderson Doniphan Johnston, was a bookkeeper for the National Treasury Department. Frances began her early education at home, before studying in Washington, D.C. private schools and graduating from Notre Dame Academy, a religious school for women in Govanstown, Maryland.

From an early age, image making was a calling. After high school, she requested that her parents send her to Paris to study drawing and painting at the Académie Julian. During her formative years, Johnston was gifted a camera from George Eastman himself, and taught to use it by Thomas Smillie, the Smithsonian Institution’s first photographer. 4

In the 1880s, Johnston began her career as a journalist, writing short form articles for newspapers and magazines and illustrating them with pen-and-ink drawings. In 1894, she opened her photography studio in Washington, D.C. on V St. NW between 13th and 14th streets.5 At the time, Johnston was the only woman photographer in the city. She opened her studio shortly after those on “photographer’s row,” like Mathew B. Brady, C.M. Bell, and Alexander Gardner, had closed up shop or passed.6 The Washington Times described her as, “the only lady in the business of photography in the city,” as she began picking up social attention. 7

The life she chose came with its challenges. As she told Ladies Home Journal in 1897:

“The woman who makes photography profitable must have, as to personal qualities, good common sense, unlimited patience to carry her through endless failures, equally unlimited tact, good taste, a quick eye, a talent for detail, and a genius for hard work.”8

Her family’s position gave her certain advantages, however – including access to many D.C. socialites, government officials and politicians. From the late 1880s to the 1910s, she documented life in the White House, from first families, to workers, to visitors, along with the architecture. After establishing her studio, she soon founded a business of professional portrait photographers and began working as a photojournalist and freelancer for numerous magazines and illustrative journals.9

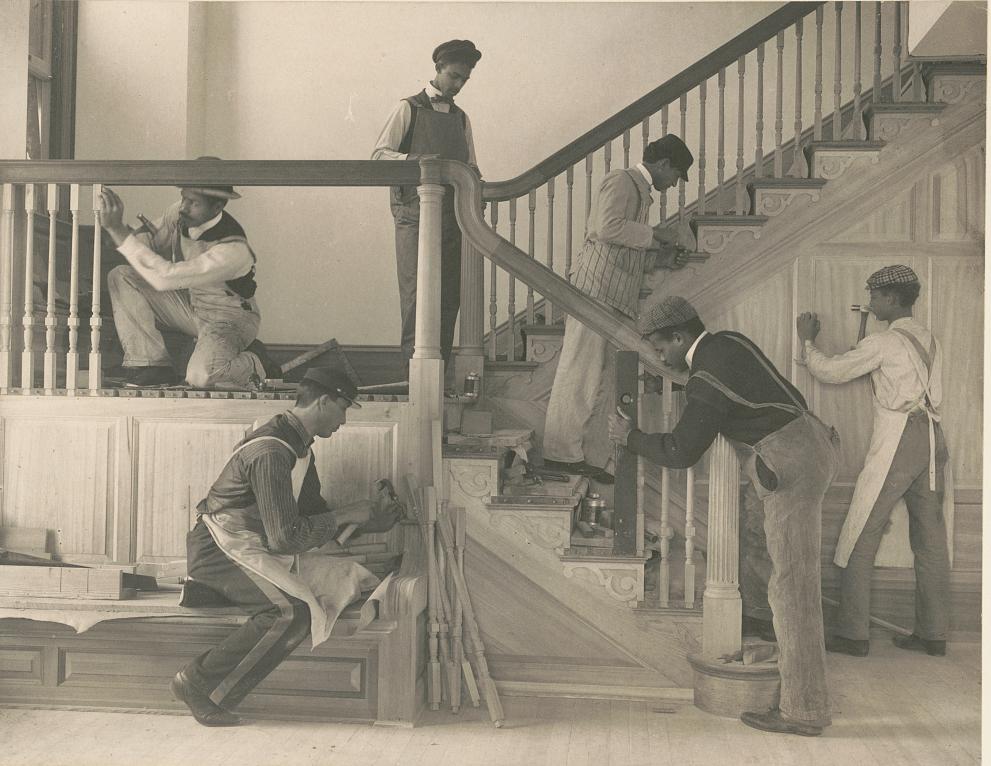

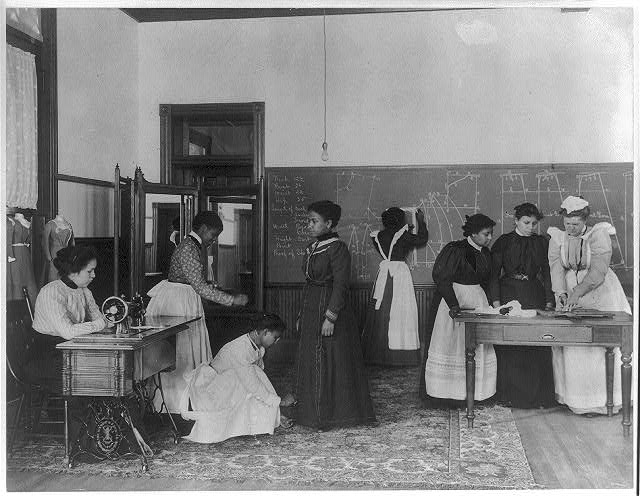

In 1899, Johnston was commissioned to photograph the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute for an exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition, a world’s fair meant to celebrate advancements over the previous century.10 Established in 1868, Hampton was founded with the purpose of instructing newly freed slaves of the South (and, after 1878, Native Americans as well).

Johnston spent weeks illustrating the school’s range of courses while also letting interested students get behind the camera.11 At the time her images were displayed, many felt like this documentation would bring a progressive, more humanistic view of recently freed slaves. However, critics have pointed out that Johnston failed to individualize her nonwhite subjects. Her photos, while described as “photojournalistic,” were mostly staged. In effect, she created the narrative for the students at the Hampton, showing them in “action” but controlling the frame.12

At the Exposition, Johnston’s photos were included in an exhibit entitled The Exhibition of American Negroes, which was organized and curated by Thomas Calloway and W.E.B. DuBois. The exhibit received several awards but, to the organizers’ frustration, relatively little mainstream American press attention.13 Perhaps that is why the prints in the book that Lincoln Kierstein would find 40 years later were not immediately identifiable.

In the years following the Paris Exposition, Johnston began shifting from a strict photojournalistic lens and moving into a more artful mindset. In 1905, she took a European tour to regain her sensibilities and interests that were being overshadowed by assignment after assignment. This was the root of her later work photographing architecture and landscapes.14

Upon returning the U.S., she moved to New York City to flourish her creative thinking in the commercial and artistic center of American photography. She moved in with photographer Mattie Hewitt, a long-time rumored love-affair and girlfriend. Together they opened a joint studio specializing in architectural photography as their romance blossomed.

As Hewitt wrote to Johnston, “…Ah I love you, love you better than even you know… Yes my dear we will turn over a new leaf and stand together in time of weakness or need of help and we must not ever again turn away head or take hand away but when I need you or you need me—must hold each other all the closer and with your hand in mine, holding it tight, I will clear away all misunderstandings or doubts and the sun will shine again…”15

Johnston and Hewitt eventually parted ways, and by 1920 Johnston found a new photographic niche: giving slide lectures to garden clubs and civic improvement organizations across the United States. With each hand-painted slide (known as a glass lantern) her images represent an American narrative that reveals class divisions.

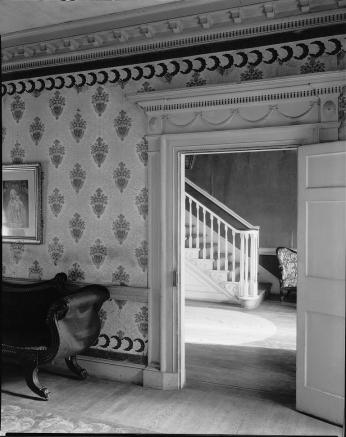

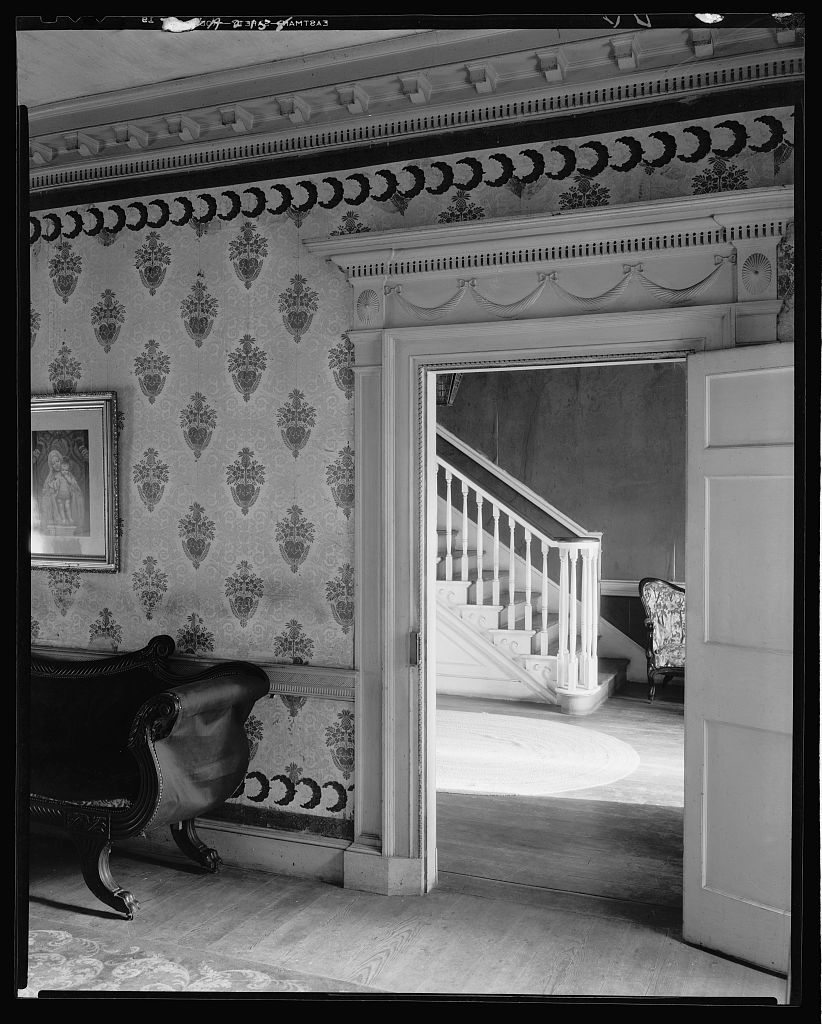

In the summer of 1927, Johnston was commissioned to photograph Chatham Manor in Fredericksburg, Virginia for Helen Devore, who had recently restored the estate. This commission led her to pursue more work documenting historic structures. Johnston dedicated much of her later career to preserving historic buildings and promoting interest in American architecture. Funded by Andrew Carnegie, her Virginia fieldwork in 1933 portrayed more than one-thousand views of buildings in sixty-seven Virginia counties.16 She spoke to local historians, architects, homeowners, and community leaders for information on each town she visited. She formed her research around looking through deeds, old plats, and used geological survey quadrangle maps for orientation.

In the 1940s, Johnston moved to New Orleans where she lived until her death in 1952. According to the Clio project’s biography, she was a regular in the city’s bars and loved to chat with visitors. When someone recognized her as a famous photographer, she agreed, “Yes, I’m the greatest woman photographer in the world.”17

It was hard to argue otherwise. Johnston’s work has proved instrumental to preservationists and historians alike and today, the Library of Congress maintains 25,000 items related to her career in its collections. These include materials from each of her photographic eras, family photographs and keepsakes, diaries, letters and images that were directly inspired by Johnston.

But perhaps her biggest recognition came from the album that Lincoln Kierstein had discovered in D.C. In 1966, the MoMA unveiled an exhibit of forty-three photographs, along with a catalog of Johnston’s work from the Hampton Album.18 This exhibition traveled through the United States and Canada, along with an essay about the photographs and Johnston by Kierstein.19 In 2019, MoMA published the images for the first time. In the book’s introduction, MoMA curator Sarah Hermanson Meister summed up their importance, “These photographs speak across time to the complicated zones where race and representation, document and art, history and the present meet.”

Footnotes

- 1

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Lincoln Kirstein." Encyclopedia Britannica, April 30, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lincoln-Kirstein.

- 2

Sarah Hermanson Meister, “The Hampton Album” The Museum of Modern Art WebSample_MoMA_Johnston_HamptonAlbum_Deluxe.pdf

- 3

The Pride and Practice of Frances B. Johnston | The Huntington. https://huntington.org/verso/pride-and-practice-frances-b-johnston.

- 4

Frances Benjamin Johnston’s Legacy in Black and White. https://www.nps.gov/crps/CRMJournal/Summer2007/article1.html.

- 5

Frances Benjamin Johnston Photograph Collection, Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. Frances Benjamin Johnston's photographic studio, Washington, D.C. Washington D.C, None. ca. 1890-ca. 1913. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/86705802/.

- 6

“Washington, DC, through the Scurlock Lens.” National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/stories/washington-dc-through-scurlock-lens.html.

- 7

Museum of Modern Art: “Frances Benjamin Johnston American, 1864-1952” Frances Benjamin Johnston | MoMA

- 8

Victoria Olsen, Smithsonian Magazine: “Victorian Womanhood, in All Its Guises” Victorian Womanhood, in All Its Guises | Smithsonian (smithsonianmag.com)

- 9

The White House Historical Association: “Frances Benjamin Johnston” Frances Benjamin Johnston - White House Historical Association (whitehousehistory.org)

- 10

Sarah Meister and Marc Sapir, Museum of Modern Art: “The Whole Picture, A conversation about Frances Benjamin Johnston’s mesmerizing photo album, now published in its entirety for the first time” The Whole Picture | Magazine | MoMA

- 11

Richard B. Woodward, The New York Times: “Overlooked No More: Frances B. Johnston, Photographer Who Defied Genteel Norms” Overlooked No More: Frances B. Johnston, Photographer Who Defied Genteel Norms - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

- 12

Jane Pierce, Harvard Art Museum: “A Cross-Collection Endeavor: Researching Photographs of Hampton Institute in Harvard’s Social Museum Collection. A Cross-Collection Endeavor: Researching Photographs of Hampton Institute in Harvard’s Social Museum Collection | Index Magazine | Harvard Art Museums

- 13

Flamini, Roland. “W.E.B. Du Bois in Paris: An Exhibition against Racist Clichés.” France-Amérique (blog), March 9, 2023. https://france-amerique.com/w-e-b-du-bois-in-paris-an-exhibition-against-racist-cliches/

- 14

Maria Ausherman, National Park Service: “Frances Benjamin’s Legacy in Black and White” Frances Benjamin Johnston's Legacy in Black and White (nps.gov)

- 15

Maria Popova, The Marginalian: “The Love Letters of Pioneering Victorian Photojournalist Fannie Benjamin Johnston” The Love Letters of Pioneering Victorian Photojournalist Fannie Benjamin Johnston – The Marginalian

- 16

“About This Collection | Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South | Digital Collections | Library of Congress.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/collections/carnegie-survey-architecture-of-the-south/about-this-collection/.

- 17

Clio Visualizing History: “The Artist & Her Life” Clio: The Artist & Her Life (cliohistory.org)

- 18

Pierce, Jane. Solving the Mysteries of the Hampton Album. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/145.

- 19

Museum of Modern Art, “Frances Benjamin Johnston, The Hampton Album” Frances Benjamin Johnston, The Hampton Album

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)