Beyond the Invitation: Chief Plenty Coups and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

On November 11, 1921, Washington, D.C. was gray and cloudy, with a light mist covering the city. Eventually, sunshine began to peek through the clouds, shining down on the thousands who had come to the District to pay their respects to one of the nation’s fallen heroes. For this was Armistice Day, a day when an unknown soldier was buried and recognized at Arlington National Cemetery.[1]

All that was known about the man was that he was an American soldier who had lost his life in France during World War I. Out of respect for all of those who died in anonymity, he was selected at random and brought back to the United States. On the day of the ceremony, his casket was shown at the Capitol, an honor usually reserved for Presidents.[2] Thousands visited him, from local residents to international dignitaries, to pay their respects before the casket made its formal procession to its final resting place, Arlington National Cemetery. To an estimated 90,000 attendees, President Harding made a call for international peace, identifying the “horrors of modern conflict” as well as “war’s distress and depressing tragedies from the state of righteous civilization.”[3] After the President concluded, a series of international leaders paid additional respects to the unknown hero, laying their highest military honors on the sarcophagus.

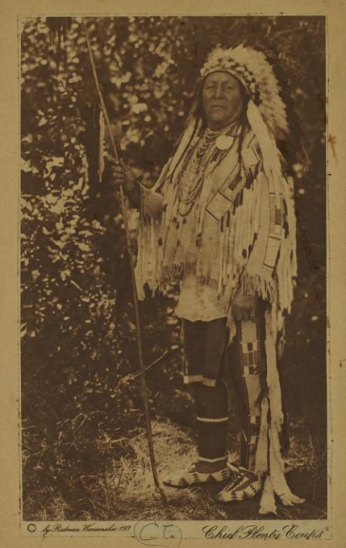

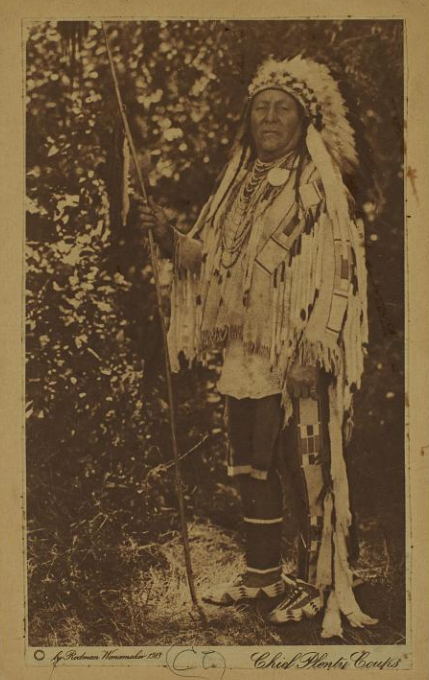

The day had been meticulously planned out, with the order of events printed in area newspapers. As the ceremony neared its conclusion, the last guest of prominence rose from his seat: Chief Plenty Coups, a distinguished leader of the Crow tribe. When he approached the sarcophagus of the unknown soldier, he took off his war bonnet and placed it on the casket, and laid his coup stick on top.[4]

And then, to the surprise of organizers, he spoke.

“I feel it an honor to the red man that he takes part in this great event, because it shows that thousands of Indians that fought in the great war are appreciated by the white man. I am glad to represent all the Indians of the United States in placing on the grave of this noble warrior this coup stick and war bonnet, every eagle feather of which represents a deed of valor by my race. I hope that the Great Spirit will grant that these noble warriors have not given up their lives in vain and that there will be peace to all men hereafter.”[5]

The speech was not part of the original plan of the ceremony; in fact, the Crow Chief had been specifically asked not to speak. In a note from General William Lassiter, Chief Plenty Coups was explicitly told that the outlined program “provides for no speeches” except for words from President Harding.[6] But with the Chief’s spoken dedication, the ceremony came to a conclusion. Taps played and there was a triple salvo of guns.[7]

Chief Plenty Coups’ inclusion in the ceremony underscored a very important aspect of history: the fallen soldier could very well have been of Native American descent. During World War I, an estimated 12,000 Native American soldiers served in the military, and tens of thousands of others participated at home working in war industries, assisting in relief efforts, or buying war bonds.[8] However, once Native American soldiers went overseas, preexisting stereotypes persisted to a fatal degree. A stereotype that Native Americans were born “warriors” led to more dangerous combat assignments, such as scouting and snipers, as military officials believed they would be more “comfortable” in these roles.[9] These assignments frequently put Native soldiers in harm's way, with Native Americans dying at a rate five times higher than U.S. forces as a whole.[10]

Given this history, the inclusion of a Native American in the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown soldier made a lot of sense. As Joseph K. Dixon, a photographer who documented the Native American experience in the early twentieth century, wrote to Secretary of War Joseph Weeks in the fall of 1921, “What more fitting than that this race of people … should have a place in the ceremony, for doubtless hundreds of unknown Indian graves are scattered from the sea to the Alps?... It will give added distinction to the ceremony—the fact that the First American Warrior should lay his tribute on the grave of the Latest Hero of War—an Unknown American Soldier.”[11] Several Native Americans were invited to attend, but the most prominent role was given to Chief Plenty Coups… and that decision served the U.S. Government’s interests beyond the ceremony at Arlington.

Going all the way back to colonial times, the relationship between the United States and Native Americans had been complicated (to put it lightly) and fraught. With westward expansion, the United States began to encroach on land that belonged to Native tribes. Decades of conflict between Native people, (mostly white) pioneers, and the U.S. Army resulted in Native peoples ceding land and resources to settlers. Diseased-ravaged Native populations and many previously nomadic groups were forced to adjust to reservation living on land allotted by the U.S. government. However, the discovery of natural resources such as coal and oil meant that Native groups struggled to maintain control over even their designated property.[12]

The actions of white settlers and government officials were not limited to physical boundary restrictions; there was a larger cultural impact as well. By 1880, a system was already being established to “assimilate the entire race” into white ideals.[13] This process of assimilation included schools and work regimes that moved Native Americans away from their traditions and cultural values. Congress even authorized the Courts of Indian Offenses, a way of enforcing policies and ensuring that tribespeople adhered to their new way of life.[14]

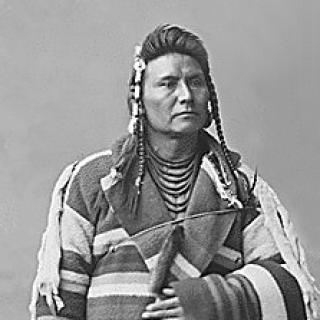

Native groups faced the impossible choice of resisting – which would lead to almost certain destruction – or adapting. For Chief Plenty Coups, the answer was the latter and it came to him in a vision, years before he became Chief in 1876. As a young boy, he foresaw the extinction of the buffalo, a major resource for the Crow tribe. His vision also showed him the encroachment of white settlers and saw that other tribes that were resistant to these invaders would fall away while his tribe remained strong. Through this vision, he determined that he should work with the United States government and white settlers, adjusting to their demands while also standing up for his people. He believed that this strategy was the best way to preserve his tribe and their culture.[15]

His vision mostly came true - in his lifetime he saw the extinction of the buffalo and the depletion of surrounding tribes and available land.[16] A majority of these changes were forced by encroaching settlers, so Plenty Coups chose to make adjustments rather than create conflict in order to preserve his tribe. He encouraged his people to cultivate land, moving the Crow away from their nomadic roots to create more permanent, agricultural settlements. He built a log cabin and founded a merchandise store for those in his tribe to trade goods. When settlers came to take their land, he advised his tribespeople to be cordial with the intruders.[17] While he encouraged the Crow to make these lifestyle adjustments, he never stopped fighting in the interests of the Crow and Native Americans everywhere. Between 1901 and 1917 he led a successful fight against Montana Senator Thomas Welsh's efforts to dissolve Crow land.[18] Plenty Coups' leadership came at an incredibly contentious time, as he had to manage these new external pressures from white settlers and government officials, while also attempting to create stability within a new format of living for his tribe.[19]

Given Plenty Coups’ approach, it was something of a no-brainer for the U.S. Government to invite him to participate in the Armistice Day ceremony. The Chief still maintained some traditional aesthetics that made him identifiable as a Crow. At the same time, he served as a symbolic figure for how Native Americans should act in the eyes of the expanding United States.[20]

The symbolism is not lost on scholars. In his book Parading Through History: The Making of the Crow Nation in America 1805-1935, Frederick Hoxie explores how external conquest forced the Crow people to adjust their traditional values, ultimately creating a new Crow community. His scholarship highlights Chief Plenty Coups’ leadership and the U.S. Government’s perception that he, “belonged to a generation that had made its peace with American expansion and was ready to give way to the demands of ‘civilization’.”[21] Through that lens, Plenty Coups’ invitation to participate in the ceremony at Arlington was not an attempt to quell ongoing issues between Native tribes and the government. His invitation was a sign that the Native people had been defeated.

This opinion was not limited to government officials. Newspapers reporting on the events of the burial painted him as something from the past, a symbolic representative of what had been. An article from the Washington Herald the day after the Armistice Day ceremony discussed in length how the nation’s “first warrior” was paying respects and honoring a soldier from the “Now”.[22] According to the author, the two men “had nothing in common yet had everything in common”. However, in the way the article described the scene at Arlington, it seemed to cast aside the Native American experience as something that is not a part of America’s present or future: “The American Indian warrior of the old time fought for what he believed to be his scared national rights against the advance of modern civilization and was beaten.”[23]

So, if this was the perception of the United States government and popular media, the question begs: why did Chief Plenty Coups choose to participate in the event?

It’s difficult to say for sure, based on available evidence. But it seems logical to think that participating in the ceremony meant something different altogether to the Crow leader. While Native Americans had lost a tremendous amount in their interactions with white settlers and the United States government, Plenty Coups and the Crow people were not defeated, at least not from their perspective.[24] Rather, by following the approach they did, the Crow had done what they needed to do in order to survive.

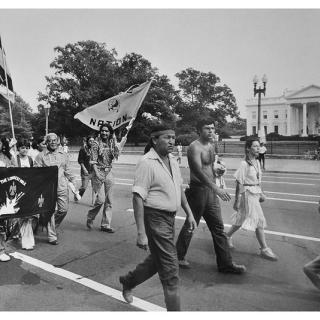

So, with his attendance – and especially his decision to go off script and address the crowd – it seems that Chief Plenty Coups was trying to call attention to that fact. His presence and his voice garnered attention for Native Americans everywhere who had lost visibility and autonomy through the early twentieth century.[25] While the Washington Herald article and other government statements had reduced the Native experience to something of the past, Chief Plenty Coups stood on that stage in Arlington and showed that Native Americans deserved a place in America’s present with, as Hoxie termed it, “a new political and cultural self-consciousness.”[26]

Attempting to unpack Chief Plenty Coups’ motivations surrounding the Armistice Day celebration is, admittedly, an exercise in speculation. We will never know exactly how Chief Plenty Coups felt about the event at Arlington. In his own biography, he refused to discuss what occurred in the years after the buffalo disappeared from the Crows’ plains. For him, it was the turning point in which the traditional lives of his people were permanently altered: "After this, nothing happened."[27]

But while his own feelings about the ceremony remain unclear, his actions were significant. Upon his death in 1932, the Crow tribe decided to honor the great man by officially viewing Plenty Coups as the last traditional Chief of the Crow people.[28]

Footnotes

- ^ William Slavens M’Nutt, “First American Warrior Honors Unknown Crusader,” The Washington Herald, November 12, 1921, 5486 edition.

- ^ Special to The New York Times, “SOLEMN JOURNEY OF DEAD,” The New York Times, November 12, 1921.

- ^ Special to The New York Times, “90,000 PAY HONOR TO OUR UNKNOWN, LYING IN STATE,” The New York Times, November 11, 1921.; “President Harding’s Pledge to World Over Grave of War Hero Buried as U.S. Mourns,” The Evening Star, November 11, 1921, 28,320 edition.

- ^ “President Harding’s Pledge to World Over Grave of War Hero Buried as U.S. Mourns.”

- ^ “SOLEMN JOURNEY OF DEAD.”; Press outlets including the New York Times and Associated Press reported that Plenty Coups gave the speech in his native Crow language and the New York Times provided the English translation of the speech included in the body of this article. Some other sources, including the Arlington National Cemetery website, suggest that there is debate about whether or not Chief Plenty Coups said anything at the event. One strong clue that he did, indeed, speak is this montage of silent video from the 1921 dedication ceremony, which includes a few seconds of footage as Chief Plenty Coups lays his coup stick on the grave. It appears to show him turn to the crowd and begin to speak before the clip ends.

- ^ John C. Ewers, “A Crow Chief’s Tribute to the Unknown Soldier,” The American West, November 1971, 34.

- ^ “President Harding’s Pledge to World Over Grave of War Hero Buried as U.S. Mourns.”

- ^ “Featured Document Display: Honoring Native American Soldiers’ World War I Service,” National Archives Museum.

- ^ “Featured Document Display.”

- ^ Smithsonian Institution, “Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces. Topics: World War I,” National Museum of the American Indian.

- ^ Jennifer Leigh Van Vleck, “Chief Plenty Coups and the American Indian Tribute to the Unknown,” Arlington National Cemetery (blog), October 29, 2021.

- ^ Frederick E. Hoxie, Parading Through History: The Making of the Crow Nation in America 1805-1935 (Cambridge University Press, 1995), 351.

- ^ Hoxie, 349.

- ^ Hoxie, 351.

- ^ Plenty Coups (Chief of the Crows) and Frank Bird Linderman, Plenty-Coups, Chief of the Crows (University of Nebraska Press, 1962), 61-73.

- ^ Linderman, 311.

- ^ Linderman, 313.

- ^ Van Vleck, “Chief Plenty Coups and the American Indian Tribute to the Unknown.”

- ^ Hoxie, Parading Through History, 355.

- ^ Hoxie, 346.

- ^ Hoxie, 353.

- ^ M'Nutt, “First American Warrior Honors Unknown Crusader.”

- ^ M’Nutt.

- ^ Hoxie, 360.

- ^ Hoxie, 365.

- ^ M’Nutt, “First American Warrior Honors Unknown Crusader.”; Hoxie, 365.

- ^ Linderman, Plenty-Coups, Chief of the Crows, 311.

- ^ “Chief Plenty Coups | AmericansAll.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)