“Vindictiveness, Vexation, and Blackmail”: Victorian Washington’s Prelude to #MeToo

In March of 1894, Washington society holds its breath. A woman is mounting a witness stand beneath the scrutiny of a crowded courtroom, dressed in black from her bonnet to her silk gloves. As she sits, she looks directly at the defendant—a United States congressman—whose disaffected mien falters a little.

This is social suicide, and she knows it.

For months the capital has followed every lurid detail about her relationship with Kentucky Representative William Breckinridge. Reporters and lawyers wait to scrutinize every word out of her mouth. The parlors and drawing-rooms of her new friends are now surely closed. The odds are staggeringly against her as a woman who has openly admitted to “imprudent conduct” with a married man. There are some who can’t believe she would show her face in public.

Nonetheless, Madeline Pollard is not one to back down from a challenge.

of promise case. [Source: Library of Congress]

Pollard was not born into high society. She grew up in rural Kentucky, where her father died early, ending her schooling and leaving her mother with six children and no means to earn a living. Pollard, wanting something beyond “a houseful of children,” saw education as her path to financial and personal independence and entertained dreams of becoming a writer.1 But without money of her own and few jobs open to uneducated women, she had to find someone to pay for it.

To this effect, she made a deal with James Rodes, a man “several decades” older than her who had previously proposed marriage. Their written contract outlined that Rodes would pay for her education. When she finished, Pollard would get a job and pay him back. If she did not repay or dropped out of school, she would have to marry him.2 With Rodes’ money, she happily attended Wesleyan College in Cincinnati, studying Latin, French, and elocution.

Pollard’s intersection with William Breckinridge began in April 1884, when they took the same train to Kentucky. The congressman, then nearly 50, struck up a conversation, asking if he did not know her from somewhere. Madeline said she did not think so, but she did know him: “You are Colonel Breckinridge.”3

That might have been the end of it, had Pollard not soon received troubling news.

Rodes was getting impatient and demanded immediate repayment. Panicked, Madeline wrote to the most powerful man she knew—Breckinridge—to see if he could help her. Breckinridge came to Wesleyan to counsel the young student, taking her to a concert in a closed carriage (citing a “throat affliction”). Only days later, the two had begun a romantic relationship that would last for a decade.4 He was already married at the time.

The relationship was a “mixed blessing” for Pollard.5 Breckinridge ensured she had money to go to school—though she transferred to the University of Kentucky in Lexington to be closer to him—and she was with a man she loved, who promised to eventually marry her. She also began to circulate in the society she always dreamed of, developing friendships with intellectuals and making the acquaintances of “Bluegrass royalty.”

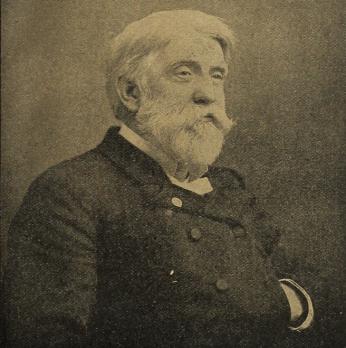

Congressman, was around sixty when Pollard

filed her suit. [Source: The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records by Madeline Pollard, 1894]

But her personal life grew more complicated. Because Breckinridge was married, it was imperative that their relationship remain secret. Her life caved to his needs, moving from city to city to avoid rumors and hide her pregnancies. She also never earned her degree: after a first leave of absence due to her 1885 pregnancy, Pollard never again attended regular classes.

Breckinridge brought Pollard to Washington after her second pregnancy in 1887. She passed the Civil Service Exam and he helped her find jobs at the Department of Agriculture and the Census Bureau. Though Breckinridge was often busy, Madeline had a thriving social life in the capital, making friends with artists and influential people whom she impressed with her intelligence.6

But nearly a decade into their relationship, tensions were growing. Breckinridge’s wife had died, and Pollard saw the perfect chance for him to make good on years of promises to marry her. But he gave no definitive answer. Frustrated and worried by rumors that he was seeing other women, Pollard wanted an engagement announced publicly.

He tried to tempt her into going to study in Germany, but she put her foot down: if she left, it would be as his fiancée. The argument was further postponed by Pollard’s third pregnancy, which ended in a miscarriage—the third child she had lost while Breckinridge’s mistress.

Stressed by the death of her baby and fed up with Breckinridge’s hesitation, Pollard did something a little rash. After reading rumors of her involvement with Breckinridge in Kentucky newspapers, she printed an official announcement of Breckinridge’s engagement to her on June 23, 1893 in the Washington Post.7

What she didn’t know was that Breckinridge was in Kentucky at that very moment—on his way to marry another woman, Louise Scott Wing. Breckinridge scrambled to contain Pollard, pleading that she “control” herself until he returned. Madeline insisted he keep his “oft-repeated” promise. If he did not, she would “without further communication with you, without delay, and without fear of consequence to you or to me, seek redress.”8

Not three days later, Breckinridge was married—but to Louise, not Madeline.

Pollard was quite rightly outraged. Marriage in the nineteenth century was an economic as much as emotional venture, and she had waited for years, only to be betrayed. Breckinridge expected no countermove, but Madeline sought her promised “redress.” She filed a bombshell breach of promise suit in D.C. court. It was potentially damning for Breckinridge but certain to ruin her. Nonetheless, it was her only legal recourse. Pollard demanded $50,000 while publicly revealing the illicit relationship, and alleging that by “tak[ing] advantage of her youth and inexperience,” the congressman came to “dominate and control her and her life.”9

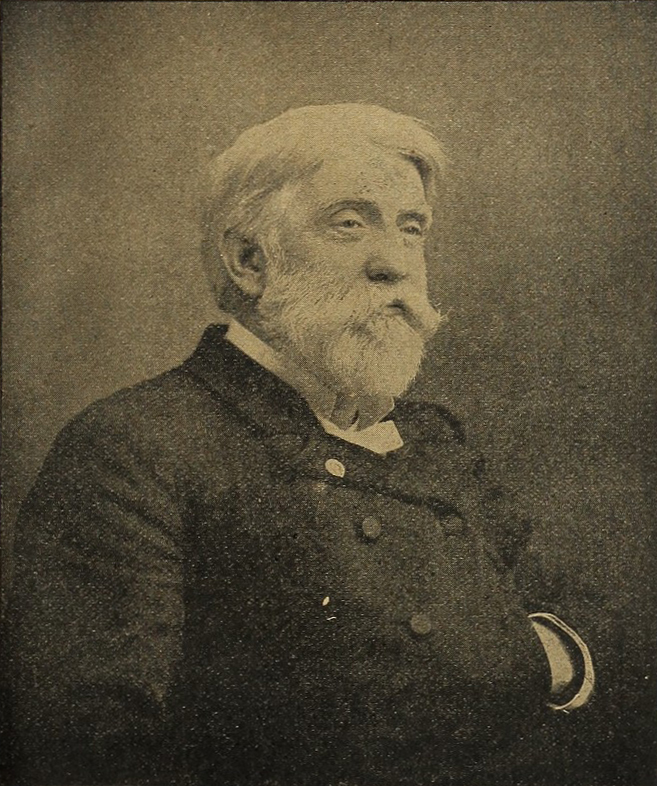

he seemed at ease, despite the severity of Pollard's

charges and testimony. [Source: Evening Star]

A flurry of press interest followed. In public, Breckinridge “did not seem to be perturbed” by the news and denied every accusation. Calmly, he told reporters that Pollard’s charges were “the result of vindictiveness, vexation, and perhaps of intention to blackmail.”10

Behind closed doors, though, he was less tranquil. When denial did not work, his legal strategy became a systematic smear campaign against Pollard, casting her as an unscrupulous social climber who had been discovered in “compromising relations” with other men. His lawyers even hired a woman named Jennie Tucker to spy on her, passing information on upcoming witnesses and legal strategies.11

Breckinridge’s strategy assumed that society would not allow a “fallen woman” such as Pollard to seriously challenge him. Gilded Age rules on sexual conduct were “viciously” punishing for women, while men were encouraged to do as they pleased—even married men like Breckinridge.12 The double standard chafed on itself as more women entered the workforce, became independent, and organized themselves, but society was hesitant to unchain a woman’s value from her chastity—or support a woman who deviated from the expected role of wife and mother.

Pollard countered moral fearmongering by publishing her own story in the New York World. She flipped Breckinridge’s narrative of the “predatory fallen woman” by detailing their consensual, decade-long affair and her ambitions for education, not money or power. “I am determined in the few ways left open to me to redeem my life,” she said, appending the original suit to her article.13

She would not play the part of the shame-faced seductress. When prosecution began, she would be in court, as she had every right to be.

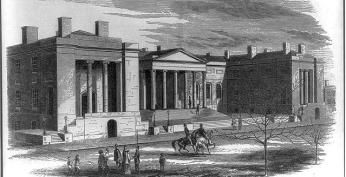

to watch the trial's proceedings. [Source: Evening Star]

Of course, the trial was the event of the season in Washington. The District courthouse just off Indiana Avenue became “crowded to its utmost capacity.” People stood “in the adjacent corridors and peered through the windows” to hear the sordid affair.14 Testimony could be so “lurid” that Judge Andrew Bradley banned women from the courtroom.15 Over the next month, Breckinridge and Pollard’s battling stories came out on the stand. Newspapers like the Evening Star faithfully delivered multi-page, illustrated accounts of each day’s proceedings. Often, it was front page material.

The trial was a brutal experience for Pollard and probably an uncomfortable one for Breckinridge. A decade of intimacy was ruthlessly dissected for the nation to see, and most of the scrutiny went solely to Madeline. She was called “a bawd, a wanton, and a woman of the town” as Breckinridge’s attorneys distorted her desire for learning into a sexual strategy for social climbing.

Lawyers surgically questioned Pollard about her actions going back to her teenage years. She defended herself against fabricated testimony of immorality, including accused residence at a “sporting-house” (a brothel).16 She even had to listen to Breckenridge deny even knowing that Pollard had ever “had any living child.”

This was after their first two children had died in orphanages, Breckinridge having persuaded Pollard they posed an intolerable risk to his career. Guilt tormented Madeline: she fainted while recounting her story.17 Her testimony illuminated a whole “shadow system” of houses, foundling asylums, and money that revealed how men hid evidence of sexual relationships.18

In her black dress and with her calm, poised manner, Pollard made a compelling witness. The Enquirer noted: “in every word and action she betrays the breeding of a lady,” not the adventuress Breckinridge wanted the jury to see. Her story was watertight; her memory “arranged like a chronological tablet.”19

Even with her painfully candid testimony and a sympathetic press, odds were stacked against Pollard: as a fallen woman, she had no social currency. But she had made friends of her own in Breckinridge’s circles, and one woman proved a crucial ally—and even the lynchpin of her case.

Julia Blackburn was the governor’s widow, Kentucky’s most eminent woman. She was also a good friend of Pollard and Breckinridge. In 1890, the Congressman had asked Blackburn to be Pollard’s chaperone, a society guardian necessary in preparation for their marriage, which he told Julia about “in a moment of excitement.”

Blackburn was Pollard’s key witness, a woman of high importance whose character and credibility was “beyond reproach.”20 If she said Breckinridge had promised—several times—to marry Pollard, her word was impossible to brush away—though Breckinridge’s attorneys tried. “This is a terrible ordeal for a lady,” she snapped during relentless cross-examination. “I can add nothing to or take back anything I have said.”

Pollard had Blackburn’s “protection,” and the old widow’s authority made up for Pollard’s outcast status.21 Madeline was now impossible to disregard.

During closing arguments, the prosecutors painted a castigating picture of Breckinridge: for ten years he had lived “a life of duplicity, of hypocrisy such as you can’t coin words to express.” As for Pollard herself, society’s condemnation was unavoidable, but “whatever there is of slime on her, comes from this defendant.”22

Surprisingly, others agreed. The jury—all men—took only two hours to consider the weeks of evidence presented to them. Swiftly, they returned to the courtroom with their verdict: Congressman Breckinridge had broken his promise to Madeline Pollard. They awarded her $15,000 (more than half a million dollars today), though they had considered up to $30,000.23

Pollard disappeared from the historical narrative—as most mistresses unfortunately do—once she separated from Breckinridge. But she led a happy and fulfilling life afterwards. Sympathetic “charitable” women took Pollard under their wings. She traveled abroad, visiting Paris, Italy, Germany, and Egypt. In London, she lived with a wealthy widow in the bohemian Chelsea neighborhood, chasing her literary ambitions and continuing to make friends with artists. For the rest of her life Madeline identified herself as a “student” or a “writer.”24

Breckinridge landed on his feet—or so it seemed. He was frustrated by the verdict (the damages were three times his annual salary), but Congress ignored petitions to censor him and he went home to seek reelection in 1895. But when he arrived, his home district revolted.

“No trained politician could have conducted a more vigorous or telling battle” against Breckinridge “than the Kentucky women.” Though they couldn’t vote, women exerted “tremendous influence,” generating the largest ever turnout for a primary in the district.25 26 They organized boycotts, held prayer meetings for his defeat, and told Breckinridge’s young male supporters they could forget about marrying their daughters.

Even amid public outrage, Madeline Pollard was not optimistic. She predicted that powerful friends and supporters would support his “campaign of vindication” and save his career. She was nearly right: Breckinridge lost by only 255 votes.27

Much work remained to be done after Pollard’s brief crusade for justice, but if her flame was brief, it was nonetheless bright. A clear double standard existed in society’s judgement of men and women, and Pollard wanted the quiet part said out loud.

Ironically, Breckinridge himself was the one to admit it. During testimony, he assured the court that Pollard had been sexually intimate with James Rodes when she asked for his advice back in 1884. Her lawyer asked Breckinridge what, knowing this, his advice had been:

“I told her that she could not afford not to marry him,” Breckinridge said.

“And that same rule would apply to a man under the circumstances?”

“If you ask me whether I would advise a young woman who had had criminal intercourse with a man to marry him, I would say yes, but with a man it would be different, for the knowledge of it by the public would destroy the woman and would only injure the man.”

“Would it not injure the man?”

“Oh, it would not injure him so much as the woman. Society works upon these things differently... I am not talking of the justice of--”

“Oh no,” interrupted Pollard’s lawyer. “I was not asking you about justice.”28

Footnotes

- 1 Miller, Patricia. Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took On Washington. Sarah Crichton Books, 2018.

- 2

Stuff You Missed in History Class. “Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge.” Video. YouTube, January 20, 2023.

- 3 Miller, Patricia. Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took On Washington. Sarah Crichton Books, 2018.

- 4 Alexandria gazette. (Alexandria, D.C.), 16 March 1894. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 5

Elizabeth A. De Wolfe. “‘Not Ruined, but Hindered’: Rethinking Scandal, Re-Examining Transatlantic Sources, and Recovering Madeleine Pollard.” Legacy 31, no. 2 (2014): 300.

- 6

Stuff You Missed in History Class. “Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge.” Video. YouTube, January 20, 2023.

- 7

The New York Times. (New York City, NY), 24 June 1893, NYT Timesmachine.

- 8 Miller, Patricia. Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took On Washington. Sarah Crichton Books, 2018.

- 9

The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894.

- 10

The New York Times. (New York City, NY), 13 August 1893, NYT Timesmachine.

- 11 Miller, Patricia. Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took On Washington. Sarah Crichton Books, 2018. P. 144

- 12

Diamond, Anna. “The Court Case That Inspired the Gilded Age’s #MeToo Moment.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 25, 2018.

- 13 Miller, Patricia. Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took On Washington. Sarah Crichton Books, 2018. P. 86

- 14 Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 16 March 1894. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 15

"William Breckinridge Breach of Promise Trial: 1894." Great American Trials. . Encyclopedia.com. (May 25, 2023).

- 16

The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894. p. 167

- 17

The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894. p. 47

- 18

Diamond, Anna. “The Court Case That Inspired the Gilded Age’s #MeToo Moment.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 25, 2018.

- 19

The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894.

- 20

Stuff You Missed in History Class. “Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge.” Video. YouTube, January 20, 2023.

- 21 The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894. P.29, 36

- 22 Alexandria gazette. (Alexandria, D.C.), 14 April 1894. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 23

The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894. p. 320

- 24

Elizabeth A. De Wolfe. “‘Not Ruined, but Hindered’: Rethinking Scandal, Re-Examining Transatlantic Sources, and Recovering Madeleine Pollard.” Legacy 31, no. 2 (2014): 300.

- 25

Elizabeth A. De Wolfe. “‘Not Ruined, but Hindered’: Rethinking Scandal, Re-Examining Transatlantic Sources, and Recovering Madeleine Pollard.” Legacy 31, no. 2 (2014): 300.

- 26

Summers, John H. 2000. “What Happened to Sex Scandals? Politics and Peccadilloes, Jefferson to Kennedy.” Journal of American History 87 (3): 825–54.

- 27

"William Breckinridge Breach of Promise Trial: 1894." Great American Trials. . Encyclopedia.com. (May 25, 2023).

- 28

The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge, The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of Court Records. American Printing and Binding Co., 1894. p. 208

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)