“His Effective Leadership”: President Hoover’s Good-Luck Possum

In the spring of 1929, the students of Hyattsville High School were riding a high. All season their sports teams had been sweeping county matches, and several championship trophies were within reach. The baseball team was especially excited: last year they had lost the county title to Upper Marlboro High, and the coming postseason would be a chance for redemption.1

But then in early May, tragedy struck: Hyattsville’s mascot Billy, a live possum, had disappeared overnight. A window was open on the back porch in the house where he lived. Did he run away? Had another team stolen him? The Evening Star theorized that “their pet must have awakened during the night and finding no one to play with, fared forth in search of the team.”2

The students searched everywhere but could not find him. The loss of Billy—“known to all the athletes of the Prince George’s County high schools”—was tragic, as well as horrendously timed.3 Now Hyattsville High would be facing the championships without a mascot.

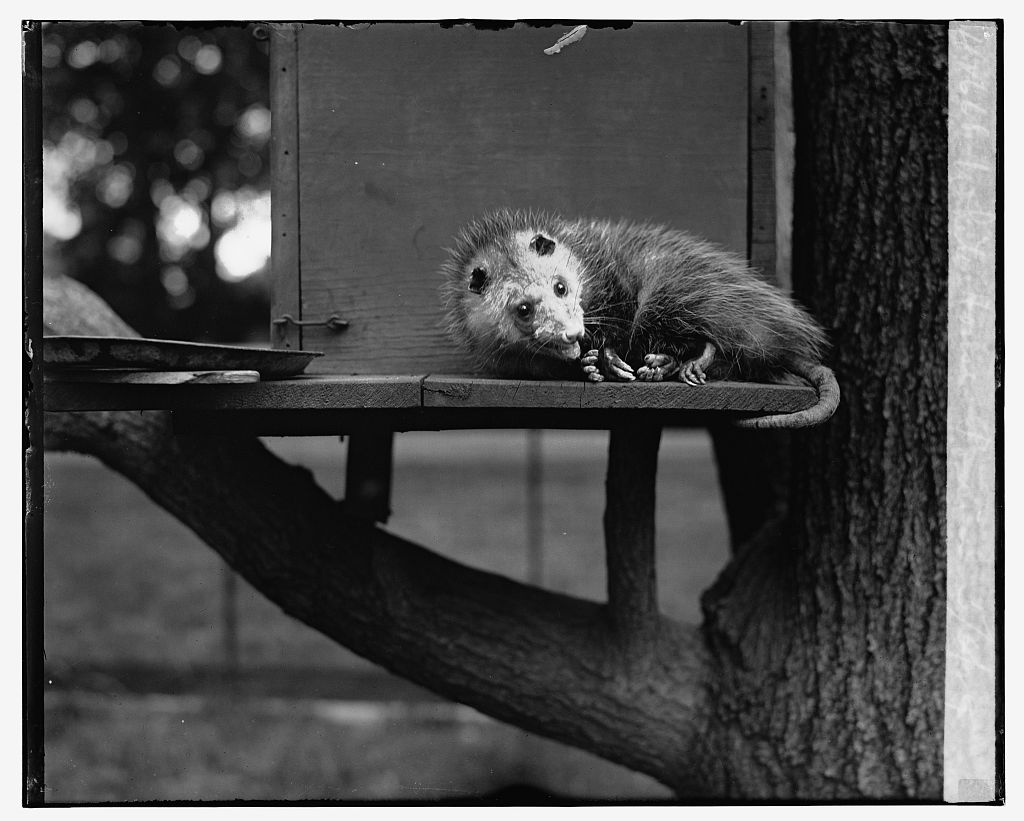

Then, on May 8th, a clue appeared in the newspaper. A possum had turned up on the grounds of the White House seemingly out of nowhere. It had been captured by the White House police after taking up residence in a “spacious cage on the south” lawn that had previously belonged to Rebecca, the Coolidge family’s raccoon. The current tenants of the White House, the Hoovers, took a liking to the animal and named him—also—Billy Possum. “For the present,” one newspaper reported, Billy was “to be retained in Rebecca’s cage” and allowed to live as a White House pet.4

Given the timing of the Hyattsville Billy’s disappearance and the arrival of the White House Billy, the students wondered if their mascot had somehow wandered down to Washington. As far as identifying the animal went, Billy looked like just about every other possum, but would come to students when they called his name. Would this White House possum do the same?

Determined to bring Billy home, a contingent of five set out for Washington from Hyattsville: students William Robinson, Eddis Donaldson, Agness Gingell and Leila Smith (“all outstanding athletes”), and Robert Venemann, the soccer team’s manager.5 When they arrived at the White House, they were escorted to the little treehouse now occupied by the possum. But when they called for him, he “refused to come out” of his new home.

Disappointed, the students had to concede that this possum was not their Billy.

But all was not lost. Hyattsville High School needed a mascot, an icon, a leader—and they realized that, though this Billy Possum was not their own, he was nonetheless a possum. And, being roommates with the president, he came with considerable cachet. They left a note for President Hoover explaining the predicament of their “lost, strayed, or stolen mascot” and how their Billy had previously “aided materially in piloting” teams to county titles.

“Tomorrow, our school is competing in the annual field meet for the county championship and next week our baseball team will enter the state championship,” the students wrote. “In the absence of our little friend Billy and to counteract any influence for bad in the event he may have found his way into the enemy camp, we are wondering if you will be kind enough to allow us to have the White House opossum.”6

Having read such a heartfelt appeal, President Hoover immediately lent the students “the first possum of the land.”7 The students were elated. Rival schools might have their mascots, but how many of those could claim a connection to the president? William Robinson, the captain of the baseball team, exclaimed to a reporter: “With the White House ‘possum for a mascot nothing can stop us now.”

Considering themselves “the luckiest… in the country,” the students raced back to Maryland with their borrowed possum.8 Their new Billy served the school nobly throughout the postseason, leading Hyattsville teams to victory in soccer, track and field, and—to William Robinson’s sure delight—baseball. When tournaments finished a month later, Billy was returned to the White House with a note of thanks to the President for his generosity in lending the school his possum.

“We cannot fail to appreciate the value of this little animal as a purveyor of good fortune,” wrote Robert Venemann, the team manager who had first accompanied the students to Washington. “We have resorted Billy Possum to the keeping of the White House in the hope that he will bring you full measure of good luck, trusting, however that with your kind permission, we may again be honored with his effective leadership in our athletic program next fall."

President Hoover even sent a note back, saying he appreciated the “formal report” of Billy’s “efficiency,” and that his time with the schools would be “incorporated into his service record.” Though the White House was his home for now, Hoover promised that Billy’s “health and spirits” would be seen to for any “further needs of the Prince George’s County high school teams.”9

Now living lavishly as a White House pet and minor celebrity among the Prince George’s County student population, surely Billy Possum approved!

Footnotes

- 1

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 19 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 2

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 23 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 3

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 23 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 4

“Billy Possum” Joins White House Entourage. (1929, May 9). The Lewiston Daily Sun, 5.

- 5

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 24 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 6

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 24 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 7

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 25 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 8

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 25 May 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 9

Winick, S. (2019, August 12). Of Possums and Presidents: Some Presidential Encounters with opossums. The Library of Congress.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)