Out of Step: Minor Threat and the Beginnings of Straight Edge

If you asked the average Washingtonian in the first half of the 1980s what was going on musically in their city, they might point out a new wavish band like the Urban Verbs. But the most impactful developments would not be fully appreciated until later. “There was plenty of other stuff happening,” observed writer Mark Jenkins, “it was only in retrospect that people saw the hardcore scene as maybe the most important thing…”1

Indeed, Washington in the 1980s served as the backdrop for the emergence of hardcore punk and the straight edge movement. In a culture that encouraged drinking, drug use, and promiscuous sex, straight edge punks remained sober as a means of resistance. The goal? “Renouncing the unattainable rock & roll myth, making music relevant for real people.”2

Straight edge was motivated by a desire to revitalize punk subcultures such as the one in Washington, D.C. Punk music had been part of D.C. culture since the mid 1970s but by the early 1980s, some punks like Ian MacKaye believed the scene had grown apathetic in its consideration that “a form of rebellion . . . was in self-destruction.”3 MacKaye vented his frustration in an interview for the zine Yet Another Unslanted Opinion: “I don’t like drinking. I’m not into the drug thing, I’m not into the punk rock media inspired ugliness that a lot of people seem to be showing. There’s no creativity in it.”4

According to musician and educator JR Rhine, “It was MacKaye who put a name—inadvertently, he claims—to punk’s Straight Edge movement” in the early 1980s.5 However, the movement’s inception began several years earlier.

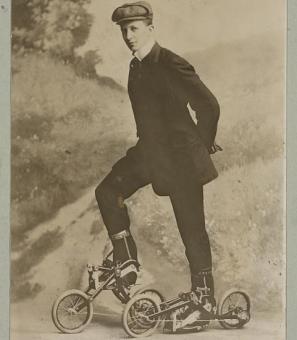

While still a teenager in the late 1970s, MacKaye and friends Jeff Nelson, Geordie Grindle, and Nathan Strejcek formed the Teen Idles. The group proudly displayed their ages on concert posters, promoting “clean rock.”6 But because they were under 18 (as were the majority of their fans) they had difficulty finding places to play. Many venues were only interested in shows for audiences 18 and over (then the drinking age for Washington) so they could sell more alcohol.

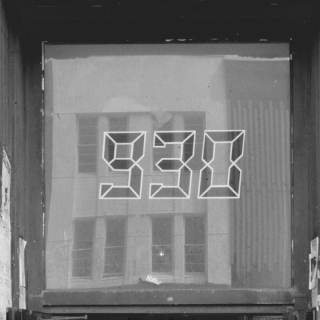

Shortly before they broke up, the Teen Idles negotiated with Dody DiSanto (formerly Bowers), the then-owner of 9:30 Club, to allow all-ages shows. Inspired by experiences touring in California, they proposed marking a big black “X” on the hands of underage patrons to identify them at the bar. DiSanto agreed, and the Teen Idles’ farewell show – opening for new wave band SVT – helped pave the way for future all-ages shows.7 Even new wave zine Washington Waves acknowledged the success of the venture, calling the show “a merger between the band and audience in tacit pandemonium.”8

At the time of their breakup, the Idles had amassed a few hundred dollars in earnings. Rather than divide the pot and go their separate ways, they decided to put out a recording to document the band. They had previously made recordings with audio engineer Don Zientara at Arlington’s Inner Ear Studios. But, as MacKaye acknowledges, “at that time…you can imagine the amount of interest that was in the world for an obscure teenage punk band that had broken up.”9 The group would have to do it themselves.

They asked Skip Groff, the owner of a local record store called Yesterday and Today Records, for help and he put them in touch with a Nashville-based company. The band would send a tape and a check, and the studio would send back 1,000 records.10 The agreement did not include liner notes and packaging so the band mates would have to assemble them themselves. As MacKaye recalls: “using scissors, we cut out every…one. And [using] Elmer’s glue, we folded every one…We did that for [our first] 10,000 records. Every 7”, we did it by hand.”11 Some copies would get a special touch: “Folding all the lyric sheets and sealing them with a kiss or a fart,” says Nelson. “We’d write S.W.A.K or S.W.A.F. on a few of them.”12

They called their new label Dischord Records. Naturally, they co-opted the “X” as a badge of honor, proudly emblazoned on the Idles' record’s cover.

After a positive review in the Touch & Go fanzine in Michigan, the Idles' record was catching on and MacKaye and Nelson decided they wanted to press more records to document the Washington punk scene. Their second release for their friend Henry Garfield’s (now Rollins’) band State of Alert helped the label gain its footing. Soon, Dischord would press records from many of DC’s most important hardcore bands.

Meanwhile, only a month after the Idles broke up, Nelson and MacKaye had started a new band – Minor Threat -- with Brian Baker and Lyle Preslar. MacKaye, who had played bass in the Teen Idles, became the band’s new singer. They played their first show on December 13th opening for DC hardcore pioneers the Bad Brains. Bad Brains proved to be an important influence on Minor Threat’s sound, with lead singer HR referring to the new band’s members as his “undergraduates” and encouraging them to pick up instruments and create music.13 Attendees of Minor Threat’s first few shows could tell something special was happening. One reviewer even predicted, “Minor Threat has the potential to be a moving force among the punk rockers.”14

In 1981, Minor Threat released two 7-inch records. Their first included a song titled “Straight Edge,” in which MacKaye claims that although he is “a person just like you” he has “better things to do/ than sit around and f*ck my head”15 – gaining an advantage because he has “gone straight edge.” The lyrics, when coupled with the brute force and precision of the band, provided not only “a compelling metaphor for the sober, righteous lifestyle advocated in the lyrics,” but “a compelling advertisement for it as well.”16

Minor Threat’s second 7-inch In My Eyes clarified this idea even further, with the song “Out of Step (With the World)” boldly proclaiming, “don’t drink/ don’t smoke/ don’t f***.” When he listened to In My Eyes, Guy Picciotto, who would later join MacKaye in Fugazi, believed “the band reached what was for me their peak.” For him and other listeners, “their thing was their precision…it was the violent clarity of their attack that distinguished them.”17

MacKaye’s ideas quickly became popular among members of the hardcore scene and – lifted from his lyrics – “straight edge” became the term for a lifestyle free of drugs and alcohol. One impassioned author wrote in the zine Most Things Suck, “by drinking, you are just showing everyone you are afraid to be different and your lack of personal strength and individuality. Being your own person, non-conformity and standing up for what you believe, that is what hardcore is about.”18

However, as straight edge grew into a national phenomenon, certain groups became dogmatic in their approach. Record label founder and Boston scene participant Curtis Casella noted that “Minor Threat…was a safe way of telling people not to drink. But when it got filtered up north to Boston it got a little eviler.”19 Bands such as Boston’s SS Decontrol were extremely condemning in their approach to straight edge, knocking audience members’ drinks out of their hands at shows. These reactions were disappointing to Minor Threat, who believed the original meaning of straight edge had been misunderstood. MacKaye denied responsibility for the movement, telling the zine Brand New Age that, “Straight Edge is an anti-obsession pro-positive song and it’s not telling people what to do, it’s not a set of rules. Straight Edge is not a movement. Straight Edge is just an idea.”20 Even Nelson and Preslar admitted they were occasional drinkers.

Conversely, not everyone in DC was on board with straight edge. One review of a Minor Threat show sarcastically commented, “excessive preaching by Minor Threat’s Ian…between numbers raised a few titters in the audience, but it is healthy to be reminded of the Ten Commandments once in a while.”21 Others were more combative, such as the band Black Market Baby, who coined the term “bent edge,” “the celebration, basically, of getting wasted and partying in connection with punk rock music.”22

In April of 1983, Minor Threat released their first and only full-length album; any zine from that summer wouldn’t have been complete without a much-anticipated review of Out of Step. One reviewer commented, “there may be hundreds of hardcore bands around, but only a handful have the talent, imagination, and excitement of these guys.”23 The album featured eight new songs and a re-recorded version of “Out of Step.”

But the “exciting new version”24 of “Out of Step” signified new tensions within the band, which were reaching a breaking point. Nelson believed that the original lyrics were too dogmatic in its proscription of “don’t drink/ don’t smoke/ don’t f***.” MacKaye reportedly became so angry when Nelson requested they re-record the song with a clearly enunciated “I” in front to become “I don’t drink/ I don’t smoke/ I don’t f***” that he punched a hole in Nelson’s bedroom door.25 However, Nelson won over in the end. In addition to adding a clearly enunciated “I” to the beginning of the song, MacKaye also intoned a service announcement further clarifying the personal significance of straight edge, putting it in plain terms that, “this is no set of rules/ I’m not telling you what to do/ All I’m saying, is I’m bringing up three things/ that are like so important to the whole world/ I don’t have to find much importance in.”26

However, as one reviewer pointed out, “there’s only one song [on the album] …which deals with Straight Edge.”27 In many ways, Minor Threat’s Out of Step signifies both the culmination and decline of the scene they helped create. Perhaps the most powerful of Out of Step’s songs is the closing track, “Cashing In,” originally written as a joke. In its ending section, MacKaye ponders “there’s no place like home/ so where am I?”28 reflecting on his alienation from the DC Hardcore scene.

By coupling “Out of Step” with a group of songs about growing resentment for the present and nostalgia for things past, “Out of Step” becomes a song more about feeling disconnected with the DC hardcore scene, perhaps because of some punk fans’ disrespect for and misinterpretation of Minor Threat’s beliefs.

The members of the band were becoming disconnected from each other as well. In a tense interview for the zine Brand New Age in 1983, drummer Nelson responded that, “our fights will become physical someday,”29 when asked how long the band planned to stay together. MacKaye acknowledged that “the other three members of the band wanted to move on and get more commercial but I didn’t.” Rather than change their sound, MacKaye advocated the band “leave Minor Threat alone and just let it be.”30 After playing their final show at Lansburgh Cultural Center in September 1983, the band broke up. Maximum Rock n’ Roll published an obituary in their December issue titled: “Minor Threat: Gone but Not Forgotten.”31

MacKaye and Nelson continued to work together at Dischord, which served to meticulously document the DC hardcore scene as it unfolded. Despite having broken up, the other members of Minor Threat convinced MacKaye to record for a final session, resulting in the Salad Days EP.32 The record contains some of Minor Threat’s best work, including the title track, a song originally entitled “Last Song” that was performed at the Lansburgh gig. The song serves as a nostalgic ode to earlier days in the scene. MacKaye sings: “Wishing for the day/ When I first wore this suit/ Baby has grown ugly/ It’s no longer cute.”33

By the time Salad Days was released in 1985, the DC scene had begun to pick up again after a period of inactivity in 1984, with a new crop of bands appearing in Minor Threat’s wake. And the personal politics of bands like Minor Threat were beginning to evolve into awareness of the city – and world – around them. Instead of interpreting “Salad Days” apathetically, it seemed that members of the scene weren’t giving up. Instead, they would “keep on struggling to keep on trying to do something.”34

Footnotes

- 1 Michael Azerrad, Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Rock Underground 1981-1991. (Boston: Little, Brown, 2001), 151.

- 2 Azerrad, Our Band Could Be Your Life, 137.

- 3 Punk the Capital: Building a Sound Movement, (Metuchen, NJ: Passion River Films, 2021), 88 min.

- 4

Ian MacKaye, interview with unattributed interviewer, Yet Another Unslanted Opinion Number 1, (1985), 10-13.

- 5 JR Rhine, “The Free Space: Ian MacKaye and DC’s Hardcore, Straight Edge Scene,” Washington History 33, no. 2 (2021), 55.

- 6 Concert flier for a performance of Teen Idles, Madam’s Organ, Washington, D.C., January 26, 1980.

- 7 Azerrad, Our Band Could Be Your Life, 127.

- 8

Bill Asp, review of Teen Idles, 9:30 Club, Washington, D.C., Washington Waves Issue 3 (1980).

- 9 Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90), (Pottstown, PA: MVDvisual, 2015), 103 min.

- 10 Rhine, “The Free Space,” 63.

- 11 American Hardcore: The History of Punk Rock 1980-1, (Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2007), 100 min.

- 12 Azerrad, Our Band Could Be Your Life, 143.

- 13 American Hardcore.

- 14

Unsigned review of Minor Threat at DC Space, Washington, D.C., in Washington Waves Issue 4 (1980).

- 15 “Straight Edge,” Apple Music, track 4 on Minor Threat First Two Seven Inches, Dischord, 1984.

- 16 Azerrad, Our Band Could Be Your Life, 136.

- 17 Guy Picciotto, “What the f*ck have you done?” in Just a Minor Threat: the Minor Threat Photographs of Glen E. Friedman, (Brooklyn: Akashic Books, 2023), 6.

- 18

David S., “Why Drink” in Most Things Suck Volume 4 (1984), 16.

- 19 American Hardcore.

- 20

Brian Baker, Steve Hansgen, Ian MacKaye, Jeff Nelson, Lyle Preslar, “Minor Threat,” interview by Mike Ross and Stafford Mather, Brand New Age 1 (1983): 4.

- 21 Unsigned review of concert performance by Minor Threat, Washington, D.C., Capitol Crisis Number 3 (1981): 15.

- 22 Roger Beebe, Denise Fulbrook, and Ben Saunders, Rock Over the Edge: Transformations in Popular Music Culture, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 343.

- 23

Steve Kiviat, review of Out of Step by Minor Threat, Thrillseeker No. 2 (March 22, 1983): 55.

- 24 Baker, Hansgen, MacKaye, Nelson, Preslar, “Minor Threat,” 4.

- 25 Mark Andersen and Mark Jenkins, Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital, (New York: Akashic Books, 2009), 134.

- 26 “Out of Step,” Apple Music, track 8 on Minor Threat Out of Step, Dischord, 1983.

- 27 Unsigned review of Out of Step by Minor Threat, Attack Number 8 (1983): 24.

- 28 “Cashing In,” Apple Music, track 9 on Minor Threat Out of Step, Dischord, 1983.

- 29 “Minor Threat,” Brand New Age 1, 5.

- 30 MacKaye, interview, Unslanted Opinion, 10-13.

- 31 “Minor Threat: Gone But Not Forgotten,” Maximum Rock n’ Roll, December 1983.

- 32 EP stands for “extended play”: it usually consists of more than one song, but fewer songs than would be on an album. Salad Days features three songs: an unfinished song called “Stumped,” a cover of the Standell’s “Good Guys Don’t Wear White,” and the titular “Salad Days,” which was originally called “Last Song.”

- 33 “Salad Days,” Apple Music, track 3 on Minor Threat Salad Days, Dischord, 1985.

- 34 MacKaye, interview, Unslanted Opinion, 10-13.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)