"Like Water and Oil": The Funk-Punk Spectacular That Rocked D.C.

No doubt music fans were intrigued when they picked up the Washington City Paper on September 23, 1983:

“Funk funk funk funk it up at the pick of the picks tonite…a combination of punk and funk that should be the hottest show of the summer. D.C.’s Trouble Funk headlines with harDCore sovereigns Minor Threat…Both Minor Threat and Trouble Funk are among the vanguard in their respective scenes, and have fanatic followings.”1

The ad underscored what some Washingtonians already knew. The District was home to two burgeoning home grown musical styles. Both were uniquely D.C. and had passionate fan bases but the scenes had been largely separate.

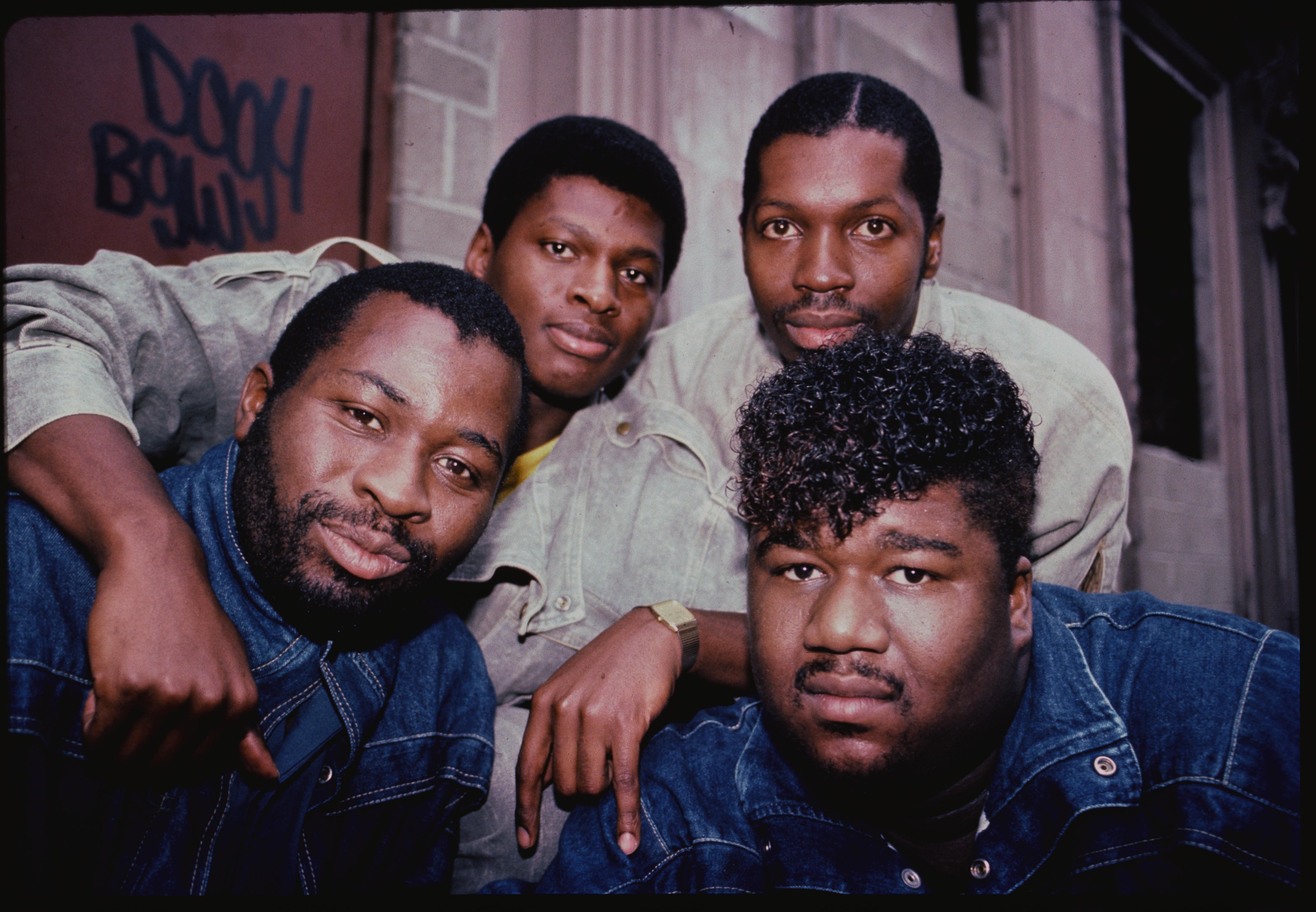

Pioneered by Chuck Brown, Go-go is a unique style of funk music, which includes Afro-Caribbean rhythms and call-and-response vocals. “The secret was to never stop,”2 notes Trouble Funk bassist Tony Fisher, who learned how to engage in crowd participation from Brown. By the early 1980s, “Go-go had emerged as the dominant form of popular music in the African American community.”3

Around the same time, Hardcore punk – or HarDCore, as it came to be known locally – was flourishing in the primarily white neighborhoods of Northwest DC and attracting fans from the suburbs.4 Growing out of the 1970s punk scene, HarDCore was a louder, faster and more aggressive style.

Despite notable differences in their sounds – which were so dramatic that Tony Fisher remarked the two styles were “like water and oil”5 – Go-go and HarDCore shared a similar ethos. As Minor Threat member Brian Baker remarked later, Go-go reminded him of early punk rock. “There’s these throngs, everyone moving in the same direction, it was a great collective, it was a great energy, the music was awesome…”6 Indeed, both “began as the music of disaffected youth, young men and women in their teens and early twenties.”7 Both genres were also largely ignored by mainstream radio and television stations, even in their hometown.

By 1983, Minor Threat’s impact on both the DC and nationwide Hardcore scene had been profound. In April of that year, they released their first and only full-length album, Out of Step. The album was a success within the scene; one reviewer commented, “there may be hundreds of hardcore bands around, but only a handful have the talent, imagination, and excitement of these guys.”8 With a formidable live presence, bands from out of town billed with Minor Threat stood no chance against their energetic performance.

Despite their success, the band’s days were numbered. Internal tensions had the members on the verge of blows. But in its waning days, the band decided to put on a unique show that brought the District’s homegrown sounds together.

As Ian MacKaye recalled later, “I always wanted to play with Trouble Funk, and I was like…we could do a show. Trouble Funk and Minor Threat…That was the first... go-go/ punk extravaganza.”9 According to Henry Rollins, a member of the HarDCore scene who would later sing for California band Black Flag, he and MacKaye “discovered” Trouble Funk while listening to a local radio station in MacKaye’s car. Rollins later wrote, “It was so good that we parked the car and just listened.” They went to see the band play live – they believed they were the only white people in the audience – where Trouble Funk “played a non-stop two-hour set and their energy and musicianship was beyond words.”10

The music was certainly different than their own but it seems that MacKaye and Rollins recognized something familiar in watching Trouble Funk. Like Minor Threat, Trouble embodied a do-it-yourself ethos, commonly associated with Hardcore and DC’s Go-go scene. The band had gotten its start in 1975, after producer and manager Reo Edwards recruited 17-year-old bass player Tony Fisher. Starting out by playing Top 40 hits, Trouble began learning the components of Go-go after observing and opening for genre pioneer Chuck Brown.

An interviewer for the zine Thrillseeker noted that “Trouble is self-sufficient, having its own sound and lighting equipment and the crews to run them.” Trouble also advocated for strong crowd participation during their shows. Tony Fisher saw their performances as trying “to build something, some kind of relationship between the group and the audience.” He added, “It’s all a matter of crowd response and getting them to respond back to you and saying the things that they want to hear.”11

When both bands were approached by Dave Rubin and Steve Blush – two concert promoters and then-students at George Washington University – about playing a show together, the answer was a resounding yes.

The concert would be held at Lansburgh Cultural Center, formerly a department store in downtown Washington. The venue was notorious for a Dead Kennedys gig in June 1983 that the fire marshal tried to shut down, accusing Blush, the promoter, of not having the right permits. When Blush attempted to call the show off, the crowd “spontaneously sat down on the floor and started chanting, demanding a show or a refund.”12 A member of the community remarked following the incident, “going there leaves rather a bad taste in your mouth.”13

Despite this, over 1,200 fans showed up to Lansburgh on September 23. Minor Threat and Trouble Funk had hoped the show would attract both of their primary audiences, with a sign outside the door reading “Unity, let’s make it happen.”14 However, it seems the attempt was largely unsuccessful, as most in the crowd were white punk fans. This was unsurprising to Robert Reed, Trouble Funk’s keyboardist, who expected “predominantly white crowds with maybe 20 percent black," at shows where the group was billed with hardcore acts. “And they all enjoy it,” he added.15

But before the show started, there was already a problem. “There was no stage,” MacKaye recalled later. “Go-go bands don’t need a stage. But punk bands definitely need a stage.”16 As an impromptu solution, the group tied tables together and set up a makeshift stage in front of Trouble Funk’s gear.

The opening band, Austin, Texas’ Big Boys, served as a perfect amalgamation of Trouble and Minor Threat. Like both bands, they also valued crowd involvement. Bassist Chris Fisher claimed, “We don’t perceive much of a line between where we stop and everybody else starts. We’ve always invited people up on the stage, whether they’re dancing, singing, or thrashing.”17 The Washington Post wrote that their set, “a mixture of glowering, metallic rave-ups and brittle, bitter funk tunes bridg[ed] the stylistic gap between the headlining acts.”18

After the Big Boys came Minor Threat. “Right from the get-go, something was wrong,”19 remarked ex-Minor Threat bassist Steve Hansgen, who was watching in the audience. In the Post, Wuelfing concurred: “the stage was immediately swamped with dancing, shouting kids.”20 Minor Threat’s makeshift “stage” seemed to stay together, but, as MacKaye remembered, “tables are not a stage…If you have 1500 people in the room, the crowd will surge, and the whole table-stage would move back. And it moved back maybe six or seven feet until it started running into the Trouble Funk gear.” 21 At such a large show, the unfortunate reality became evident. It seemed “the joyous blurring of boundaries between audience and performer that had formed the heart of the initial HarDCore experience no longer seemed possible.”22

The band itself echoed that sentiment when they premiered a new song then appropriately titled “Last Song.” (It would be renamed “Salad Days” and became the title track for the EP Minor Threat recorded after their breakup.) The lyrics long for the earlier days of the scene, which, in MacKaye’s eyes, had become distorted by the time Minor Threat broke up.

“Wishing for the day/ When I first wore this suit/ Baby has grown ugly/ It’s no longer cute.”23

To other members of the crowd, there was nothing abnormal about Minor Threat’s set. One reviewer wrote that although “Minor Threat came on next and did their usual thing and everyone got into them,” unfortunately, “the sound was loud, but not clear and that took away from their set.”24

Trouble Funk was up next and as Fisher recalled, Minor Threat was “going to be a hard act to follow.”25 But most of the punk fans, who had stayed to listen to Trouble Funk’s set, would not be disappointed. “Trouble came on and played a good and long set. They played their songs continuously with no breaks in between them,”26 in contrast to Minor Threat, who stopped their set multiple times. The fans who stayed were “rewarded with a properly grand finale,” wrote Wuelfing. “Punks and funk fans alike danced euphorically, leaving exhausted but happy.”27

Although Minor Threat’s show at Lansburgh would be their last, their effect on the HarDCore scene was felt for years afterward. Most immediately, the joint concert inspired a series of punk/ Go-go combination shows that sustained a local scene searching for a new identity following the dissolution of one of its foremost bands. For a period in 1984, Go-go shows and albums were promoted and reviewed in punk zines. Reviewers seemed excited and engaged for what would happen next in the world of Go-go, with one writing, “the bands involved in it…are gaining in musicianship and showmanship every time I see them.”28

Unfortunately, however, the Go-go and Hardcore scenes never fully integrated. The racially divided geography of Washington kept the two communities distanced from each other. By 1985, many members of the punk scene seemed more interested in the next wave of punk bands than what was going on in Go-go and vice versa.

All the members of Minor Threat went on to join or form other bands that were active in the DC scene. Perhaps most significantly, Ian MacKaye went on to found Fugazi, a band that was sustained for over 15 years and continued to embody the DIY ethos of Minor Threat. Meanwhile, Trouble Funk has been a constant in the D.C. music scene for nearly 50 years. It continues to perform and attract crowds to this day, embodying Big Tony’s words about the secret of Go-go: “Never stop.”

Footnotes

- 1 “City Lights: September 23 – September 30,” Washington City Paper, September 23, 1983, http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:287634.

- 2 Sarah Godfrey, “Trouble Funk’s Big Tony Talks about the Band’s 35 Years as a D.C. Go-Go Institution,” The Washington Post, May 18, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/trouble-funks-big-tony-talks-about-the-bands-35-years-as-a-dc-go-go-institution/2013/07/01/988bf80e-e254-11e2-aef3-339619eab080_story.html.

- 3 Kip Lornell and Charles C. Stephenson, The Beat!: Go-Go Music from Washington, D.C. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 31.

- 4 JR Rhine, “The Free Space: Ian MacKaye and DC’s Hardcore, Straight Edge Scene,” Washington History 33, no. 2 (2021), 55.

- 5 Tony Fisher, “Interview: Trouble Funk’s Big Tony,” interview by Jeff Mao, Red Bull Music Academy (April 12, 2017), https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/04/trouble-funk-feature.

- 6 Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90), (Pottstown, PA: MVDvisual, 2015), 103 min.

- 7 Lornell and Stephenson, The Beat!, 30.

- 8 Steve Kiviat, review of Out of Step by Minor Threat, Thrillseeker No. 2 (March 22, 1983): 55, http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:38147.

- 9 Salad Days.

- 10 Henry Rollins, liner notes for Trouble Funk Live (Infinite Zero Records), 1998.

- 11 Tony Fisher and Taylor Reed, “Trouble Funk,” interview with unattributed interviewer, Thrillseeker No. 2 (March 22, 1983): 24-6, http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:38147.

- 12 When the show resumed, there was only time for one forty-minute set, a disappointing end to a show where four bands had been slated to perform for a then steep ticket price of eight dollars. For more, see Mark Andersen and Mark Jenkins, Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital, 4th ed. (New York: Akashic Books, 2009), 142.

- 13 “D.C. Clubs,” Zone V Fanzine, Issue 1 (1983), 38, https://hdl.handle.net/1903.1/45975.

- 14 Wuelfing claims the audience was more integrated, claiming, “by the end of the first set, a sizeable contingent of Trouble Funk’s following had gathered and were exchanging curious glances with the punks.” Howard Wuelfing, “Punk & Funk,” The Washington Post, September 26, 1983.

- 15 Richard Harrington, “Funky Punk,” The Washington Post, September 18, 1983. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1983/09/18/funky-punk/807e3e66-64dd-41aa-ad9f-68f2c87bdf59/.

- 16 Peter Hutchins (@PeterHutchins), “Ian MacKaye Talking about Minor Threat Playing Shows with Trouble Funk,” YouTube, March 7, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mZIyeRf8OPg.

- 17 Chris Gates, Tim Kerr, Randy Turner, “Big Boys,” interview with Jim Saah, Zone V Fanzine, Issue 2, (1983): 12-16, https://hdl.handle.net/1903.1/45974.

- 18 Wuelfing, “Punk & Funk.”

- 19 Salad Days.

- 20 Wuelfing, “Punk & Funk.”

- 21 Hutchins, “Ian MacKaye.”

- 22 Andersen and Jenkins, Dance of Days, 148.

- 23 “Salad Days,” Apple Music, track 3 on Minor Threat Salad Days, Dischord, 1985.

- 24 Unsigned review of concert performance by Minor Threat, Trouble Funk, Big Boys, and N.Y. Static Disruptors, Lansburgh Cultural Center, Washington, D.C., DCene Fanzine Issue 1 (1983), 9, https://hdl.handle.net/1903.1/40339.

- 25 Fisher, “Interview.”

- 26 Unsigned review of Trouble Funk, 9.

- 27 Wuelfing, “Punk & Funk.”

- 28 Unsigned review of concert performance by Chuck Brown, Washington D.C. Thrillseeker Number 3 (1984), 16.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)