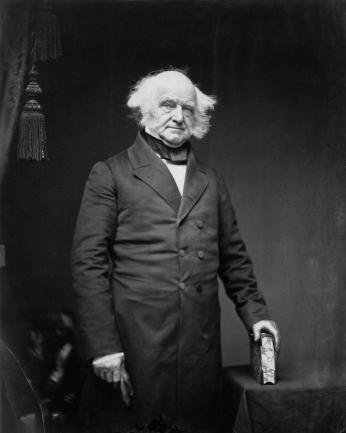

Whatever Happened to Martin Van Buren’s Presidential Tigers?

When speaking of presidential pets, Americans have always had a particular love for the weirdest and wackiest four-legged inhabitants of the White House. Past presidents have kept everything from antelopes to zebras, even loaning their animals out to zoos or nearby schools. Unfortunately, when reality within the White House walls can be as strange as fiction, it can be hard to disentangle myth from fact.

Speaking of which, have you ever heard of President Van Buren’s beloved pet tigers?

The story, repeated by sources all the way up to the National Park Service, goes like this. During Martin van Buren’s presidency, he received a gift from the Sultan of Oman. The ship Sultana had docked in New York, stocked with pearls, a golden sword, fine Arabian horses—and two tiger cubs. Van Buren was delighted with the present and immediately brought the tigers to the White House.

His fun was spoiled when Congress got wind of the animals, ordering the President to get rid of them at once. By accepting the Sultan’s gift, Van Buren had violated the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution, which prevented the Chief Executive from receiving foreign gifts, no matter how fuzzy or cuddly they were. After a protracted argument with Congress, Van Buren eventually had to admit defeat, and gave the tiger cubs up to a zoo.1

The story is repeated in online articles and listicles about presidential pets. A fun fact about Van Buren’s brief possession of pet tiger cubs even made it onto Snapple bottle caps.2 The only problem is that the whole thing is probably made up—at least the bit about the tigers.

How did we end up saddling President Van Buren with two tiger cubs he never owned? The likely answer probably comes from two separate gift-giving incidents during his presidency: one with horses, and another with lions.

In December of 1839, the Sultan of Omar and Muscat, Said bin Sultan, wrote President Van Buren notifying him that he was sending a ship loaded with tokens of friendship for his new ally (the Omani empire had recently helped an American vessel that had run aground near Muscat, resulting in expanded diplomatic relations).3 These included 150 pearls, a carpet, shawls, a “gold-mounted sword” and two Arab Nijd horses.

Van Buren wrote back saying that he appreciated the gesture but that the Constitution prevented him from receiving the gifts. By “declining your valuable gift, I do but perform a paramount duty to my country, and that my sense of the kindness which prompted the offer is not thereby… abated”.4

Unfortunately, it was too late for the President to do anything. The ship, the Sultana, arrived in New York with all the luxurious presents the Sultan had promised. The captain of the ship wrote that he was duty-bound to deliver them: “I can now carry out the Imaum’s intentions only by requestion that they may be considered as intended for the Government of the United States, and that you will… take such measures for the acceptance of them as you may deem proper.”5 The State Department had little choice but to accept, and led the fine Arabian horses off the ship, unloading pearls and rosewater behind them.

The problem of the lions had begun months earlier in Tangier, Morocco, where consul Thomas Carr had been explaining for months to the Sultan and other officials that neither he nor any other American official could accept expensive gifts—especially animals. In a culture where gift-giving held high importance, this could be hard to understand. When Carr told a governor he was “perfectly out of [his] power” to accept any gifts, the governor could not fathom how a consul could “interfere” in the relations of two state powers.

If a Moroccan agent, the governor said, “refuse[d] to convey a present to his master [he] would very justly have his head cut off” and the refusal declared an insult.6

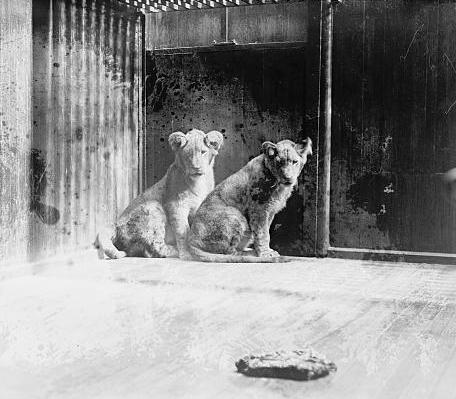

After this conversation, Carr sat down to write another letter to the Sultan to “prevent the presentation” of any gifts. But before it could be sent, a Moroccan officer arrived with the worst possible present: two adult lions, one male and one female. They were tokens of good faith between the two governments.

An alarmed Carr insisted that he couldn’t accept them. The Consulate had no power to accept such a gift, never mind space to keep the animals. What about the President, the officer suggested. No, not the President. Then they would be for Congress. Congress had resolved not to accept any more foreign presents; the Constitution forbade it. The officer then asked who wrote the Constitution.

“The People,” Carr replied.

“Then,” said the officer, “If Congress will not receive them, then the Emperor desires them to be presented to the people.”

Carr recounted all of this in a harried and apologetic letter to President Van Buren. He had done his very best to insist, but the official had been immoveable. “My determination is as strong as yours,” he had said. “It will cost me my head if I disobey—I will leave them in the street.”7 Without other options, Carr caved. He had both animals held in a reception room while he penned a letter to the State Department.

“They are to me a great expense and inconvenience,” he wrote. He begged permission to send them to America, given that “it will be impossible to dispose of them in this neighborhood.” They were “the finest animals” and would surely “sell for more than enough” to cover expenses.8 The State Department’s reply arrived—not before Carr had been stuck with the lions for three months. Carr’s actions were “properly appreciated” by Van Buren, who gave permission for the lions to come via public or merchant vessel as soon as possible.

In this way, both the horses and lions sent to Van Buren had gotten bundled up into one issue: these gifts were coming whether the United States was ready or not. Constitutionally, the President couldn’t accept them. Diplomatically, he couldn’t not accept them. What was he to do?

Van Buren, far from snatching all these animals up to keep in the White House, took the delicate matter to Congress. “I deem it my own duty,” he wrote to the legislature, to request “the adoption of legislative provisions pointing out the course which [Congress] may deem it proper for the Executive to pursue in any future instances where offers of presents by foreign states… may be made under circumstances precluding a refusal.”9

Congress dealt with the problem at once. In June of 1840, the House received a resolution from the Senate which would allow Van Buren, in these delicate circumstances, to accept the gifts and then “dispose” of them, with the proceeds going to the Treasury. The House Committee on Foreign Affairs amended the proposition to direct the funds instead to “different charitable institutions for the support of Orphans in the District of Columbia; provided that the sword… be deposited in the State Department.”10

Standard disagreements ensued: one representative asked why the motion specified D.C. charities as opposed to national ones, another maintained the Treasury would handle the money better. A North Carolinian asked if he might send some rose water to Charlotte.

Then, an elderly John Quincy Adams stood and asked if the House might discuss the resolution’s legality. This resolution was “an entire new thing, and a very dangerous thing.” Adams believed that no President or officer of the United States had “any authority… to accept presents from any foreign country”. If Congress allowed the president to accept these gifts to dispose of them, they might one day write another law letting the civil servants “accept and keep” presents.11

At this point, he was interrupted by several other members who defended the legislature’s powers. Adams was overturned 55 to 110 on the grounds that his objection was “imaginary” and Congress’ right to authorize presidential gifts was “express.” Van Buren himself, unlike the myth claims, was not present for the debate.

On July 20, Congress resolved to allow Van Buren to accept all presents to the U.S. Government made by Morocco and Oman. What could not be “conveniently… deposited” in the State Department would go to the Treasury.12

Van Buren set about “disposing” of his gifts. The pearls, sword, and carpet were kept by the State Department, and later became part of the Smithsonian’s collections. In 1955, the mannequins in the First Ladies’ Hall of could be seen wearing Omani pearls and standing on the Sultan’s gifted carpet.13 The other items were sold.

None of the animals were sent to any zoos (the National Zoo did not open until 1889). One of the horses was allegedly bought by former U.S. Secretary of War, General John Eaton.14 The lions, on the other hand, went to auction in Philadelphia’s Navy Yard. In September, the Baltimore paper Pilot and Transcript reported that a Mr. Robert Davis had bought them both. We don’t know how much the horses sold for, but the Treasury netted a neat $375 for the lions.15

So, when Van Buren never owned tigers nor fought Congress to keep any, why does the myth persist? For one, it’s an easier story to tell. As an illustration of the Emoluments Clause, two tigers wrenched out of poor Van Buren’s hands by Congress is far more digestible than a tale with horses in one direction, lions in another, and a Congress unsure what to do with them all. As the two stories converged, two horses and two lions may have become two lions, and those two lions then transformed into two tigers.

For another, history—even history as trivial as presidential pets—is shot with inconsistencies. The Presidential Pet Museum claims, without citations, that the tigers were sent in 1837. The reason they were confiscated from Van Buren is that, because they began their journey during Jackson’s administration, they now belonged to the state.16 The Emoluments Clause had nothing to do with it. Even contemporary sources could be misleading. One Virginia paper claimed (completely inaccurately) that the Sultana had also brought female Circassian slaves as gifts for the President, and that Congress might make an exception to the Emoluments Clause “in view of Mr. V.B.’s widowhood.”17

Ultimately, Martin van Buren may get to keep his imaginary tigers—at least in the public consciousness. The real story certainly doesn’t fit so neatly onto a bottlecap!

Footnotes

- 1

NPS. “‘Sorry Mister President, No Tigers Allowed In the White House.’” Lindenwald Distance Learning Activity Program . National Parks Service. Accessed July 19, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/mava/learn/education/upload/Full-Tiger-Activity.pdf

- 2

Tilton, Greg. “Snapple Fact #1183: Martin van Buren Was given Two Tiger Cubs While He Was President.” Rumor Flies, August 22, 2018. https://www.rumorfliespodcast.com/snap-judgment/tag/martin+van+buren.

- 3

Eilts, Hermann F. A Friendship Two Centuries Old: The United States and the Sultanate of Oman. Washington, D.C.: The Middle East Institute, 1990.

- 4

United States Congress. Acts and Resolutions Passed at the First [and Second] Session[s] of the Twenty-Sixth Congress of the United States: With an Appendix, Containing All Public Treaties Made and Ratified Subsequently to the Publication of the Laws of the Preceding Session, and All Proclamations by the President, Promulgated Within the Same Period, That Affect Any Law Or Treaty of the United States. Washington D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=LYEFAAAAQAAJ&lpg=RA14-PA5&pg=RA14-PA5#v=onepage&q=lion&f=true

- 5

United States Congress. Acts and Resolutions…Washington D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=LYEFAAAAQAAJ&lpg=RA14-PA5&pg=RA14-PA5#v=onepage&q=lion&f=true

- 6

United States Congress. Acts and Resolutions…Washington D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=LYEFAAAAQAAJ&lpg=RA14-PA5&pg=RA14-PA5#v=onepage&q=lion&f=true

- 7

United States Congress. Acts and Resolutions…Washington D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=LYEFAAAAQAAJ&lpg=RA14-PA5&pg=RA14-PA5#v=onepage&q=lion&f=true

- 8

United States Congress. Acts and Resolutions…Washington D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=LYEFAAAAQAAJ&lpg=RA14-PA5&pg=RA14-PA5#v=onepage&q=lion&f=true

- 9

United States Congress. Acts and Resolutions…Washington D.C.: Blair and Rives, 1840. https://books.google.com/books?id=LYEFAAAAQAAJ&lpg=RA14-PA5&pg=RA14-PA5#v=onepage&q=lion&f=true

- 10

United States. Congress. “Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States Being the First Session of the Twenty-Sixth Congress.” 1st Session pg. 1007, 1097 https://www.congress.gov/browse/26th-congress

- 11

United States. Congress. “The Congressional Globe.” 1st Session pg. 454-5 https://www.congress.gov/browse/26th-congress

- 12

U.S. Congress. U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 5 -1845, 24th through 28th Congress. United States, - 1845, 1836. Periodical. Pg. 409 https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v5/

- 13

Henson, Pamela. “Don’t Look a Gift Horse in the Mouth? Problematic Donations to the Smithsonian.” Smithsonian, 2013. https://www.si.edu/Content/Governance/pdf/Archives_06-24-2013.pdf.

- 14

Eilts, Hermann F. A Friendship Two Centuries Old: The United States and the Sultanate of Oman. Washington, D.C.: The Middle East Institute, 1990.

- 15

The pilot and transcript. [volume] (Baltimore, Md.), 02 Sept. 1840. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83016475/1840-09-02/ed-1/seq-3/>

- 16

Presidential Pet Museum. “Martin Van Buren’s Tigers,” 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20231129022737/https:/www.presidentialpetmuseum.com/martin-van-burens-tigers/.

- 17

Martinsburg gazette. [volume] (Martinsburg, Va. [W. Va.]), 14 May 1840. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc .gov/lccn/sn84038468/1840-05-14/ed-1/seq-2/>

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)