The Forgotten Story of Washington’s First Race Riot

In the mid 1830s, Washington stood on edge as pro and anti-slavery forces battled for influence. Conditions were ripe for D.C.’s first race riot, which erupted in August 1835 when a lynch mob targeted Beverly Snow, a successful free black restaurateur. Long ignored by local officials and historians, the Snow Riot sprang from white bitterness over the city’s prosperous free black community and previewed sectional tensions that would soon plunge the nation into the Civil War.

Established in the South by the Compromise of 1790, Washington harbored strong Southern sympathies in the decades following its founding and hosted America’s largest slave trading depot in Alexandria, then part of the District.1 But as the number of free blacks eclipsed the enslaved population by 1830 and abolitionist speakers and pamphlets began trickling in, white Washingtonians feared the antebellum social order and their privileged place in it and would be upended.2

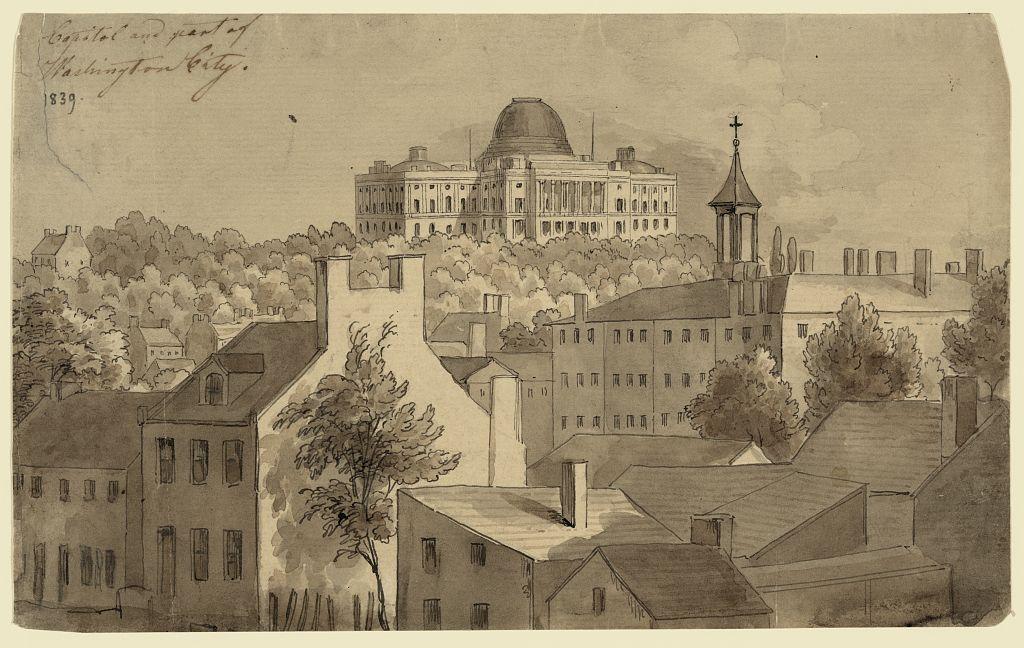

While Washington’s architects harbored grand ambitions, in 1835 the city of some 30,000 still looked more like a backwater market town than a modern European capital.3 Livestock grazed on the White House lawn, a putrid canal lined what is today the National Mall, and the poorly paved Pennsylvania Avenue forced visitors to trudge through “an inch or two of fine dust.”4

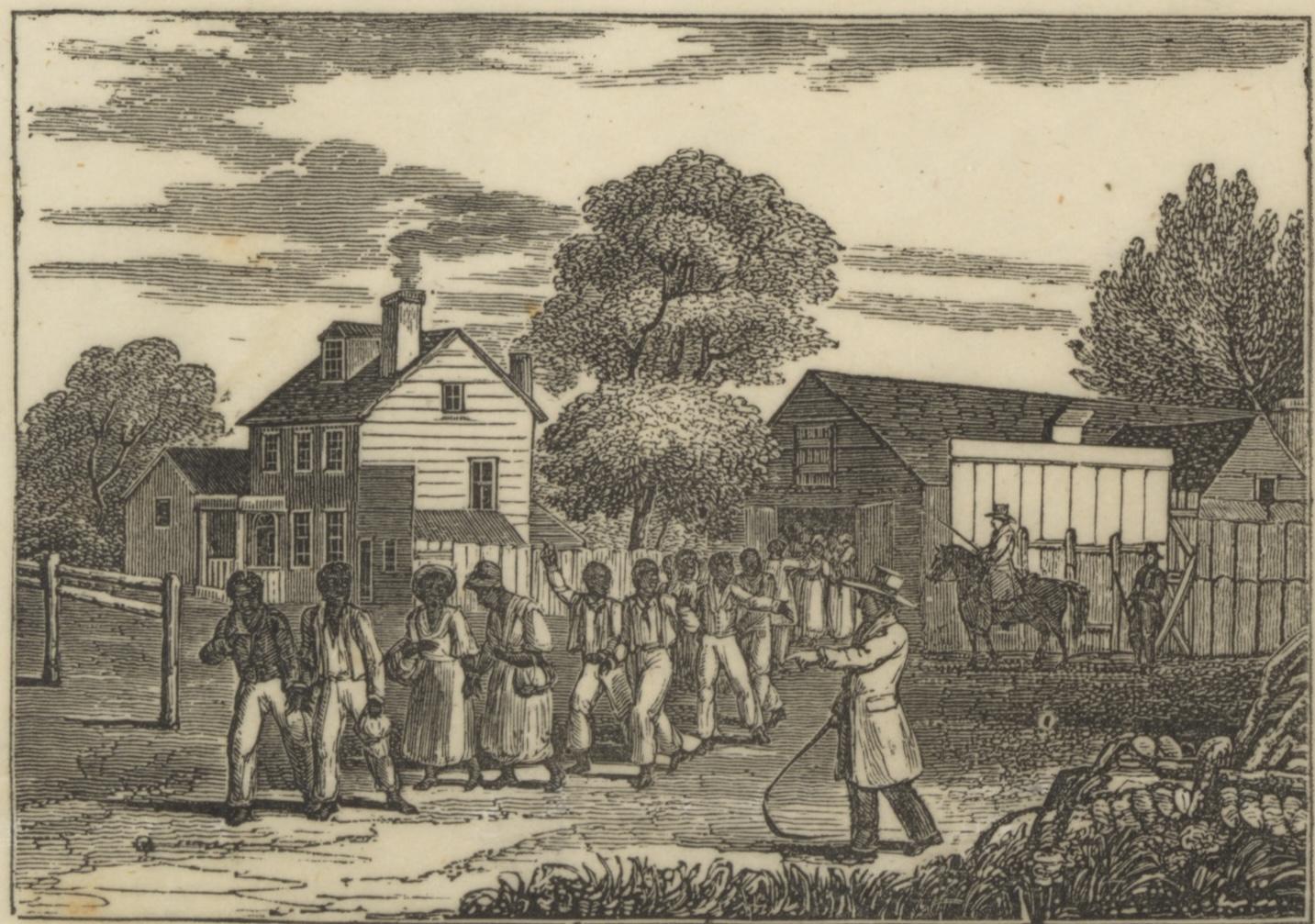

Due to its position on the Potomac River, Washington played a key role in the booming internal slave trade, as dealers transported thousands of enslaved persons from the Upper to Lower South to meet the ever-growing demand for labor on cotton plantations. The city abounded with “dimly lit pens” that held soon-to-be-sold enslaved men, women, and children, many of whom had just been separated from their families or even illegally snatched off the streets by individuals looking to make a quick profit.5

Against this backdrop of human misery, anti-slavery advocates, both black and white, began fighting back and petitioning Congress to ban the slave trade or slavery altogether in the District. In the summer of 1835, the American Anti-Slavery Society organized the country’s “first direct mail campaign,” sending bagfuls of printed abolitionist materials to civic and religious leaders in Washington and other Southern cities.6

Many white residents grew outraged, not only with the pamphlet campaign but also by the increasing affluence of their black neighbors. At the time D.C. afforded its population of more than 6,000 free blacks a degree of social and economic mobility unheard of in the South, with a number of black-owned schools, churches, and businesses flourishing.7

One such success story was Beverly Snow, a formerly enslaved cook from Lynchburg, Virginia, who operated one of Washington’s first true restaurants at the corner of Sixth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue in the basement of a three-story brick building next to the Indian Queen Hotel.8 Snow’s Epicurean Eating House offered innovative amenities like private tables and a wide-ranging menu consisting of locally sourced foods like roasted pheasants, oysters, green turtle soup, and “every other luxury that the season can afford,” as one 1833 ad in the Daily Globe put it.9

Aside from his French-inspired cooking skills, Snow was known for catering to white and black patrons alike, including famous names like Massachusetts orator Daniel Webster and South Carolina pro-slavery radical John C. Calhoun.10 Amid an increasingly bitter political atmosphere, Snow advertised his restaurant as a neutral space open to all “lovers of good living.”11

Unfortunately for Snow and despite his professed apoliticism, his status as a popular black entrepreneur was enough to draw the ire of some white Washingtonians. His flare, refined tastes, and newspapers ads which radiated self-confidence threatened to serve as a model for more free blacks to follow.

“It is safe to say that no black man, free or enslaved, had ever dared to speak so freely and publicly to the white people of Washington City,” writes journalist Jefferson Morley, author of Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key, and The Forgotten Race Riot of 1835.12

A major spark that ignited Washington’s racial hostilities came on August 4, 1835, when enslaved 19-year-old John Arthur Bowen became drunk opposite the White House after attending an H Street debating society that advocated for black “education, temperance, and freedom.”13 Upon arriving home, Bowen picked up an ax and walked into the bedroom of his enslaver, Anna Maria Thornton, a Washington socialite and widow of U.S. Capitol designer William Thornton.

Although Bowen never attacked Thornton, who would later testify in his defense and petition for a presidential pardon, proslavery Washingtonians were furious. They feared Bowen had been incited by that summer’s pamphlet campaign and saw his drunken mistake as the first step in a bloody slave uprising like that organized by Nat Turner in Southampton, Virginia, four years earlier.

After Bowen’s arrest, a lynch mob quickly formed outside the jail at Judiciary Square, to the chagrin of Francis Scott Key, famed author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” who in 1835 was serving as D.C. District Attorney. Key, himself a slaveholder, arrested and charged with sedition Reuben Crandall, a white doctor recently arrived from New York whom Key and others blamed for distributing abolitionist papers and inciting the local black population to revolt.14

With both Bowen and Crandall protected behind bars, the mob searched for new targets of its fury and found one in Beverly Snow. The crowd was mostly composed of “poor and insecure” white laborers known as “Mechanics,” a group highly resentful of the economic competition and opportunities that free blacks like Snow represented.15 Their ranks were swelled thanks to an ongoing strike at Washington’s Navy Yard, which had resorted to bringing in black workers from Baltimore, further enraging the mechanics and inflaming their racial animosities.16

A rumor quickly spread that Snow had “spoken in disrespectful terms of the wives and daughters of Mechanics,” as one local newspaper reported.17 Another paper claimed Snow’s offense was “two-fold,” writing that “letters had been found in his possession showing that he was concerned in the nefarious schemes of the Northern fanatics in regard to Slavery” in addition to “very derogatory” language he had directed at the mechanics’ spouses.18 Both offenses, the author emphasized, merited the “strongest anger.”19

“God knows whether he said those things or not,” wrote Michael Shiner, an enslaved painter at the Navy Yard who recorded major city events in a diary.20 No one would ever publicly corroborate the rumors, even when challenged by Snow in a D.C. paper.21

The truth of the whispers didn’t matter to the mechanics, who swarmed into the eating house on August 11 intent on finding and lynching Snow. While Snow successfully escaped to Virginia, the next morning the mob returned and “in a short time cut down the [restaurant’s] sign, and broke and destroyed most, if not all the furniture in the house, not forgetting to crack a bottle of ‘old Hock [wine]’ now and then.”22 The Snow Riot had begun.

The rioters avowed “their determination to scour the city in search of inflammatory pamphlets and fanatical pamphlet mongers, their accomplices, aiders or abettors” and systematically attacked Washington’s free black community over the course of the next several days.23 D.C. militia and U.S. Marines guarded government buildings but did little to stop squads of roving mechanics as they destroyed black establishments, including an African Methodist Episcopal Church schoolhouse on South Capitol Street and the debating society Arthur Bowen had attended.24

“The mechanics did not attack all free blacks or all schools,” Morley writes.25 “They pursued the small group of black men who were doing the most to undermine the slave system in the seat of the American government.”

Order was gradually restored with the arrival of militia detachments from Alexandria and Georgetown and the return of President Andrew Jackson from vacation on August 17, but the Snow Riot would leave an indelible scar on Washington society. The city had nearly torn itself apart in a violent attempt to uphold white supremacy.

“We could not have believed it possible that we should live to see the Public Offices garrisoned by the clerks, with United States troops posted at their doors, and their windows barricaded, to defend them against citizens of Washington,” wrote the National Intelligencer.26 “Will not such a state of things open the eyes of the more considerate among the agitators[?]”

Following the riots, black Washingtonians found their position more precarious than ever. The Common Council ordered the police to “inquire into the propriety and expediency of prohibiting negroes and mulattoes, whether bond or free, from assembling together for any purpose whatever, after sun-down,” and banned blacks from holding certain shop licenses.27

One Alexandria Gazette commentator implored “every man representing a slave holding State, to come out and show himself” against the “evil spirit of Abolition” in the wake of the pamphlet campaign and debates held by Congress that December over slavery.28 Continued fear over losing their valuable slave markets propelled Alexandria to lobby for its successful retrocession to Virginia in 1847.

While the riot had left dozens of houses, schools, and businesses in ruins, somewhat happier fates met the individuals at the center of the mob’s rage. Bowen was pardoned on July 4, 1836, and Crandall acquitted by a jury, although he died in January 1838 of tuberculosis contracted from his prolonged stay in the D.C. jail.29 Snow and his wife Julia moved north to Toronto, Canada, where they continued to run a string of successful restaurants.30

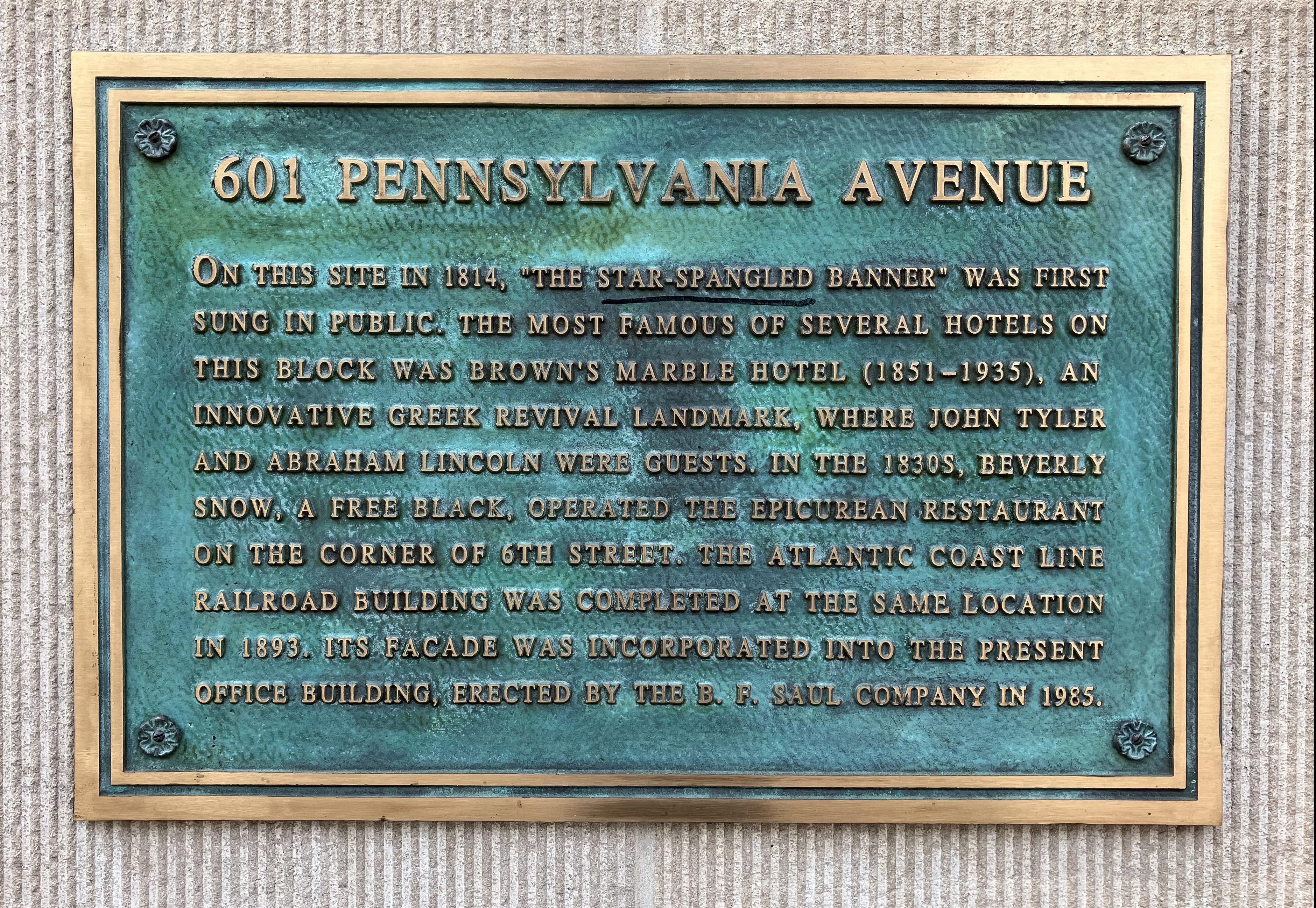

The only physical reminder of Snow in D.C. today is an oxidized plaque on the facade of 601 Pennsylvania Avenue. It reads simply that “Beverly Snow, a free black, operated the Epicurean Restaurant” at the site in the 1830s, with no mention of the riot that upended his life and forever changed Washington.

Footnotes

- 1

Mary Beth Corrigan, “Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.,” Washington History 13, no. 2 (Winter/Fall, 2001/2002): 5.

- 2

U.S. Census Bureau (1832). Abstract of the Returns of the Fifth Census.https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

- 3

Ibid.

- 4

National Intelligencer, reprinted in Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA, 17 April 1833). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 5

Mary Beth Corrigan, “Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.,” Washington History 13, no. 2 (Winter/Fall, 2001/2002): 5.

- 6

Nancy Pope, “America’s First Direct Mail Campaign,” July 2010. https://postalmuseum.si.edu/america’s-first-direct-mail-campaign

- 7

U.S. Census Bureau (1832). Abstract of the Returns of the Fifth Census.https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

- 8

Jefferson Morley, Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key, and The Forgotten Race Riot of 1835 (Doubleday 2012), 31.

- 9

“Health Bought Cheap,” National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C., 15 October 1833).

- 10

Morley, 95.

- 11

“Health Bought Cheap,” National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C., 15 October 1833).

- 12

Morley, 34.

- 13

Morley, 105.

- 14

Jefferson Morley, “The ‘Snow Riot,’” The Washington Post (Washington, D.C., 5 February 2005).

- 15

Ibid.

- 16

"The Diary of Michael Shiner: Entries from 1831-1839". history.navy.mil., 60.

- 17

National Intelligencer, reprinted in Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA, 18 August 1835). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 18

“Riot at Washington,” Virginia Free Press (Charlestown, VA, 20 August 1835). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 19

Ibid.

- 20

"The Diary of Michael Shiner: Entries from 1831-1839". history.navy.mil., 60.

- 21

Morley, 168.

- 22

National Intelligencer, reprinted in Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA, 18 August 1835). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 23

“Riot at Washington,” Virginia Free Press (Charlestown, VA, 20 August 1835). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 24

Morley, 158.

- 25

Morley, 155.

- 26

National Intelligencer, reprinted in Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA, 18 August 1835). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 27

Ibid.

- 28

“To Henry A. Wise,” Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA, 21 March 1836). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 29

Jefferson Morley, “The ‘Snow Riot,’” The Washington Post (Washington, D.C., 5 February 2005).

- 30

Morley, 244.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)