DC’s Spy Mailboxes: The Story of CIA Mole Aldrich Ames

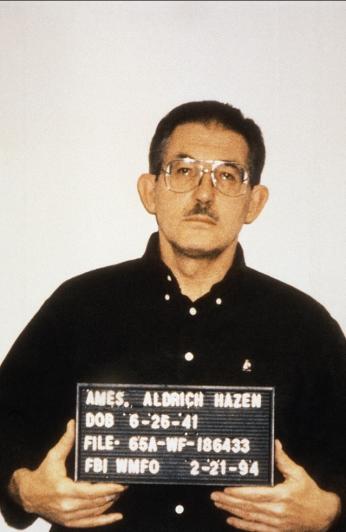

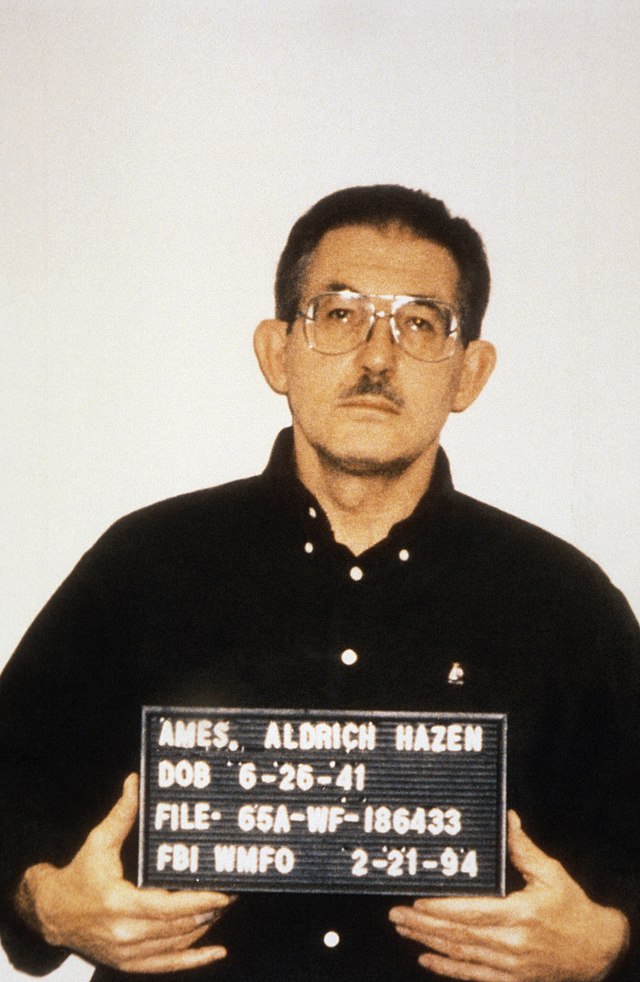

30 years ago, FBI agents descended upon a cozy corner of Arlington to arrest one of the most destructive spy-turned-moles in United States history. For nearly a decade, career CIA officer Aldrich “Rick” Ames fed some of his agency’s most sensitive intelligence to the Soviet Union—a betrayal that compromised dozens of agents and led to the execution of at least ten.1

Ames’ and his wife’s arrests on Presidents’ Day, 1994 sent shockwaves through Washington and shattered the near-mythical status enjoyed by the CIA, which had for years refused to believe it could harbor a traitor capable of selling out the lives of Soviets recruited to spy on behalf of the U.S.

“They died because this warped, murdering traitor wanted a bigger house and a Jaguar,” said then-Director of Central Intelligence James Woolsey, who resigned the next year amid congressional uproar that the agency had failed to suspect Ames even as his personal wealth ballooned.2

While he refused to dismiss any staff as a result of the Ames debacle, Woosley admitted the need to “change the culture of the CIA to no longer resemble “a fraternity [...] wherein once you are initiated, you're considered a trusted member for life.”3 Ames’ 31-year CIA career epitomized that brotherhood and all the highs and lows it afforded.4

“They made a great effort, as do some units in the military, the Foreign Service, to cultivate a sense of being in the elite. Kids respond to that. Young men and women respond to that. And certainly I did,” Ames told a New York Times interviewer in July 1994 as he awaited transfer from his Alexandria jail cell to a maximum-security federal prison.5 “There was a sense of fun.”

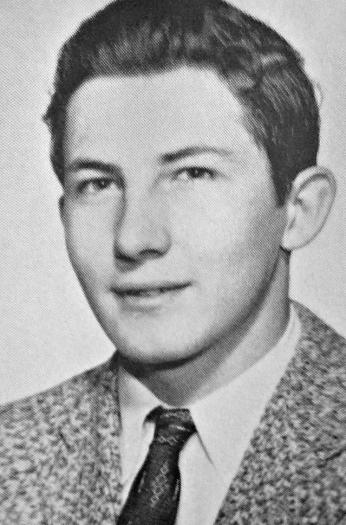

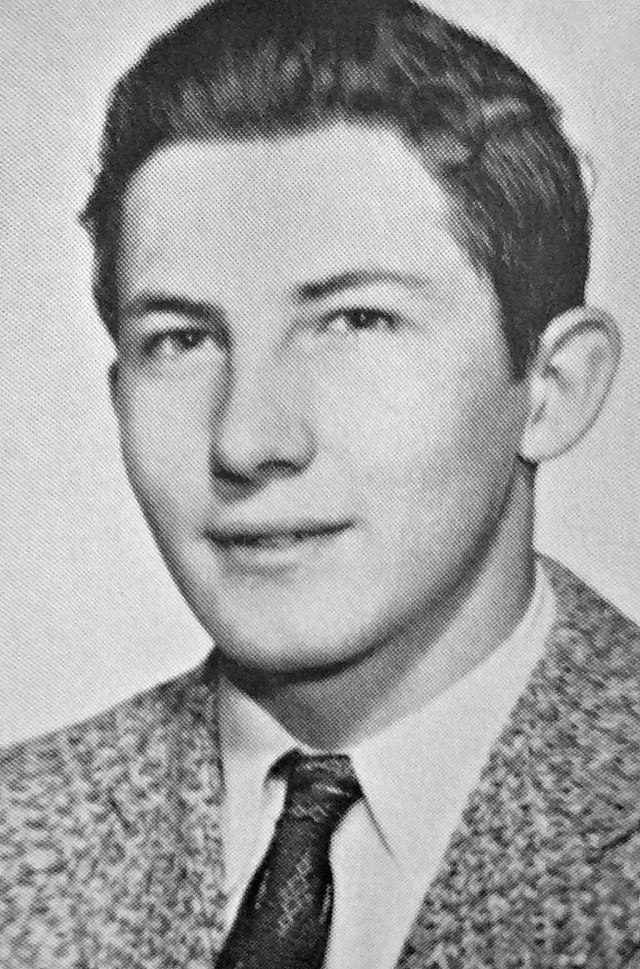

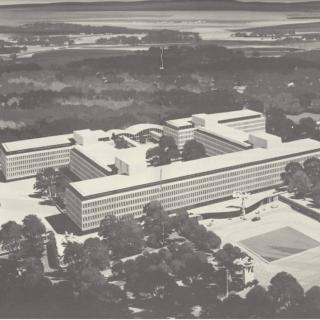

Born in River Falls, Wisconsin on May 26, 1941, Aldrich Hazen Ames was no stranger to the intelligence community during his youth.6 In 1952, his family relocated to Langley, Virginia and again to Southeast Asia for two years after Ames’ father Carleton joined the CIA's Directorate of Operations.7 Upon completion of his Asia tour, the elder Ames received a critical performance review that noted his alcohol dependency, a trait that his son would soon inherit.

After finishing his sophomore year at McLean High School in 1957, Ames landed a summer job at the CIA working as a records analyst responsible for marking classified documents and making fake paper money for officer training programs.8 He continued the gig for the next two years before enrolling at the University of Chicago in the fall of 1959.9

Despite Ames’ dreams of pursuing theater, it didn’t take long for the agency to pull him back into its orbit. In the summer of 1960 he worked as a painter at a CIA facility before dropping out of Chicago amid failing grades and eventually joining the agency full-time in early 1962 in another clerical role.10

Ames worked as a document analyst while earning a B.A. in history from George Washington University over the next five years, a span during which he was also arrested for several alcohol-related incidents.11 In spite of the run-ins with the law and a low psychological test score, in 1967 Ames gained acceptance into the CIA’s Career Trainee Program, which churned out case officers responsible for recruiting and managing agents.12

Initially stationed undercover in Ankara, Turkey, Ames worked to recruit and turn Soviet intelligence officers against their own country.13 Though he met with some success, his superiors believed Ames was unfit for field duty and he spent the remainder of the 1970s stateside learning Russian and working for the Soviet-East European (SE) Division in Virginia and New York City.14 His prospects improved in New York, where he received positive reviews managing high-level Soviet assets, despite his continued heavy drinking and tendency to procrastinate.

Things began to irreversibly unravel for Ames’ personal and professional life when he accepted a two-year posting to Mexico City in 1981. His marriage to former CIA officer Nancy Segebarth fell apart after a string of affairs, including one with Maria del Rosario Casas Dupuy, a CIA informant and cultural attaché at the Colombian embassy in Mexico.15 Ames returned to the States in 1983 and married Rosario in 1985, by which time his costly divorce from Nancy and his new wife’s expensive spending habits exerted overwhelming financial stress, according to his later testimony.16

“It was not a truly desperate situation but it was one that somehow really placed a great deal of pressure on me,” Ames told Senator Dennis DeConcini (D-Arizona) in 1994.17 “Rosario was living with me at the time [...] I was contemplating the future. I had no house, and we had strong plans to have a family, and so I was thinking in the longer term.”

With his position in the Department of Operations, Ames had widespread access to clandestine CIA counterintelligence operations against the Soviets. With this access in mind, in April 1985 Ames crossed his rubicon and devised “a scam to get money from the KGB."18

That month Ames officially turned traitor as he approached contacts at the Soviet Embassy with the names of double agents he believed were “essentially valueless” to the CIA in return for $50,000.19 Though he claimed to initially envision a one-time deal to ease his debt, Ames soon realized he had “crossed a line [and] I could never step back.”20

In June 1985, Ames again met unprompted with a Soviet official and provided documents that “identified over ten top-level CIA and FBI sources” in what the CIA later described as the “largest amount of sensitive documents and critical information, that we know anyway, that have ever been passed to the KGB in one particular meeting.”21 The Soviets would ultimately pay Ames more than $2 million for the intelligence he provided.22

Assigned next to Rome, Ames continued meeting with the KGB and passing along sensitive names and intel. The Russians would pick up Ames, dressed in a jacket and baseball cap, for late night meetings, which frequently ended with Ames “having had the better part of a bottle of vodka” by his own admission.23

Back in DC by 1989, Ames utilized “dead drop” sites to leave documents and signal his handlers from the Soviet Embassy.24 Ames and Rosario welcomed a son the same year and purchased a split-level $540,000 house in Arlington.25 By this time, at least one colleague had grown suspicious of Ames, who used a cover story that his newfound wealth—and purchases ranging from a Jaguar luxury car to thousands of dollars’ worth of international phone calls—stemmed from his wife’s Colombian family.

As soon as Ames began divulging the identities of agents, the KGB moved swiftly. The CIA eventually lost nearly all of its active agents in the Soviet Union and recruitment ground to a halt.26 Though Ames was terrified by the KGB’s rapid arrest and execution of CIA sources, he passed two CIA polygraph tests in 1986 and 1991 and initially skirted the scrutiny of a team assembled to investigate the leaks.27

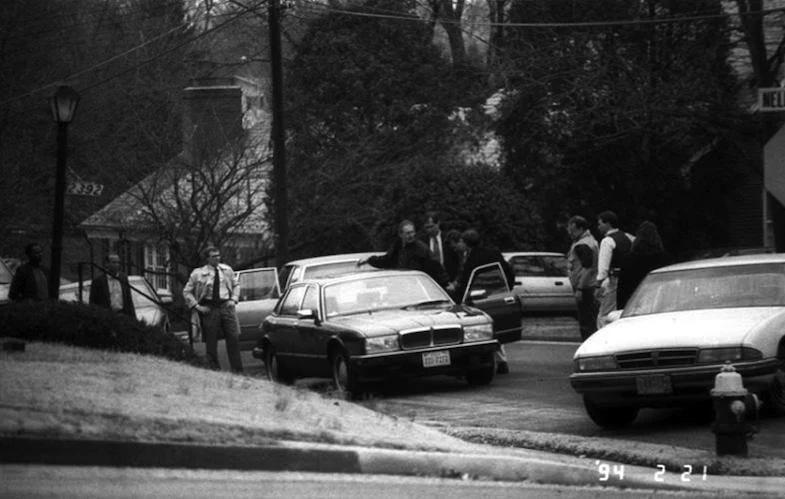

Only in 1993 did the CIA and FBI finally launch a full-scale 10-month investigation of Ames, with agents sifting through trash from his North Randolph Street home, tapping his phone, and even trailing his car in a light airplane.28 By early 1994 they had seen enough. With Ames set to fly to Moscow on an official trip, warrants were signed for his and Rosario’s arrest.

“What’s all this about?” Ames cried as he was pulled from his Jaguar and handcuffed on the morning of February 21, 1994.29

“You’re making a big mistake! You must have the wrong man!”

When made public the next day, the arrests took Washington by storm. Residents and the press flocked to two blue U.S. Postal Service mailboxes that Ames had marked with chalk to let his Soviet contacts know he was ready to meet. Located at 37th and R streets NW and Garfield Street and Garfield Terrace NW, the “spy mailboxes” stood as a potent reminder of the Cold War waged in some Washingtonians’ front yards.30

“I used to mail love letters from here at 4 a.m.,” 22-year-old Georgetown graduate student Brent Schindele told The Washington Post of the 37th Street location.31 “Do you think I was being watched?”

“We were astonished when we saw the mailbox on TV,” said one postal worker who declined to give their name to the Post, stressing “I don't have anything to do with that spy stuff.”32

Ames and Rosario, who acknowledged knowing her husband had received cash and met with the Soviets, pleaded guilty on April 28, 1994.33 While Ames received life imprisonment without the possibility of parole, Rosario got a five-year sentence through a plea agreement.

Sitting in the Alexandria jail in July 1994, the thin, bespectacled Ames’ “hair and skin have grayed perceptibly,” wrote his New York Times interviewer.34 Although “smooth, beguiling, sometimes charming” on the surface, Ames harbored “an emptiness where pain or rage or shame should be.”35

Speaking during eight hours of one-on-one interviews, in between his usual grillings by federal agents, Ames admitted that in addition to money he felt helping to eliminate the CIA’s Soviet sources would in turn help protect himself.

“What happened to them also happened to me,” he explained.36 The reporter then asked if Ames wished he had left the agency ten years earlier. As of 2024, the 83-year-old Ames remains incarcerated at a U.S. federal penitentiary in Indiana.37

“Yeah. [Long pause.] My son would have his parents. [Long pause.] My wife would have a husband,” Ames replied.“That's it.”

Footnotes

- 1

“Victims of Aldrich Ames,” Time, 22 May, 1995. https://time.com/archive/6727449/victims-of-aldrich-ames/

- 2

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 3

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 4

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 5

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 6

“Aldrich Ames: American Spy,” Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 26, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica,_Inc.

- 7

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 8

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 9

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 10

“Aldrich Ames: American Spy,” Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 26, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica,_Inc.

- 11

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 12

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 13

“Aldrich Ames.” FBI, May 18, 2016. https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/aldrich-ames

- 14

Tim Weiner, David Johnston, and Neil A. Lewis, Betrayal: The Story of Aldrich Ames, an American Spy, (Random House, 1995), 176.

- 15

Weiner, Johnston, and Lewis, 33.

- 16

Weiner, Johnston, and Lewis, 33.

- 17

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 18

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 19

“Aldrich Ames.” FBI, May 18, 2016. https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/aldrich-ames

- 20

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 21

An Assessment of the Aldrich H. Ames Espionage Case and Its Implications for U.S. Intelligence: Report Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1994. https://irp.fas.org/congress/1994_rpt/ssci_ames.htm

- 22

Bill Powell, Treason: How a Russian Spy Led an American Journalist to a U.S. Double Agent (Simon & Schuster, 2002), 14.

- 23

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 24

“Aldrich Ames.” FBI, May 18, 2016. https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/aldrich-ames

- 25

Weiner, Johnston, and Lewis, 144.

- 26

“Victims of Aldrich Ames,” Time, 22 May, 1995. https://time.com/archive/6727449/victims-of-aldrich-ames/

- 27

Weiner, Johnston, and Lewis, 163.

- 28

Weiner, Johnston, and Lewis, 5.

- 29

Weiner, Johnston, and Lewis, 9.

- 30

“Even a mailbox has its 15 minutes of fame,” The Washington Post, 23 February, 1994. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1994/02/24/even-a-mailbox-has-its-15-minutes-of-fame/4f3daacd-317d-4d15-b6ab-77f5ec68fbb4/; “FBI watched, listened, court affidavit shows,” The Baltimore Sun, 24 October, 2018. https://www.baltimoresun.com/1994/02/24/fbi-watched-listened-court-affidavit-shows/

- 31

“Even a mailbox has its 15 minutes of fame,” The Washington Post, 23 February, 1994. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1994/02/24/even-a-mailbox-has-its-15-minutes-of-fame/4f3daacd-317d-4d15-b6ab-77f5ec68fbb4/

- 32

“Even a mailbox has its 15 minutes of fame,” The Washington Post, 23 February, 1994. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1994/02/24/even-a-mailbox-has-its-15-minutes-of-fame/4f3daacd-317d-4d15-b6ab-77f5ec68fbb4/

- 33

“Aldrich Ames.” FBI, May 18, 2016. https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/aldrich-ames .

- 34

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 35

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 36

“Why I Spied; Aldrich Ames,” The New York Times Magazine, 31 July, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/31/magazine/why-i-spied-aldrich-ames.html

- 37

“Why some aging spies won't walk out of U.S. prisons, long after the Cold War,” CBC, 17 February, 2024. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/aldrich-ames-captured-spies-punishments-1.7100439

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)