The Oldest Home in Washington... is From Massachusetts?

Our nation's capital is home to a treasure trove of historic architecture. From well known structures like the Library of Congress and the White House, to 19th and 20th century residential row houses, Washington D.C is unique in its preservation of buildings. However, on a quiet street in Kalorama sits a home that is especially noteworthy. A three story Georgian mansion, The Lindens, as the home is known, stands as the oldest residential home in the District. Yet what makes this 271 year old residence even more amazing is that it was built nearly 500 miles away.

In 1754, Robert “King” Hooper, a wealthy New England merchant built a stately Georgian home on Sylvan Street in the village of Danvers, Massachusetts.1 He decided to call it “The Lindens” in reference to the tunnel of linden trees that lined the main driveway. Using it as his summer residence, Hooper, a loyalist sympathizer to Great Britain, opened his residence to General Thomas Gage in 1774. Gage, once the Commander-in-chief of the British Army and then the Governor of the Province of Massachusetts, shared Hooper's feelings of British loyalty. Gage would occupy the home for three months with Hooper by his side, turning the home into the central hub for Loyalist affairs in the colony. After the American Revolution, the home remained in the Hooper family until 1798 when it was sold.2 Over the next 130 years, The Lindens changed hands several times, but by 1933, it was in a state of disrepair and was beginning to fall apart.

That same year, 500 miles away in Washington D.C, Miriam Hubbard Morris and her husband George Maurice Morris were looking for a home. George, an attorney who would later become president of the American Bar Association, and Miriam, a fertilizer heiress, married in 1918, and had a shared love affair with early American antiques.3 The Morrises collected like mad, and eventually purchased a plot of land at 2401 Kalorama Rd. NW with the intent to construct a reproduction of a historic 18th century home to house their growing collection of furniture and decorative arts. However, the 1929 market crash proved to be the Achilles heel for this plan. The cost to build new homes skyrocketed, much to the chagrin of Mr and Mrs. Morris. With their idea to build a home in shambles and running out of space for new acquisitions, Miriam eventually made a suggestion in 1933: instead of building a replica of a historic home, why not purchase an actual one? Given the nation's financial troubles, Miriam's plan to buy an existing house and move it to their plot would be a more economical option than constructing a brand new one.4 After deciding on this course of action, the hunt was on for the Morris’s "new" dwelling.

Miriam and George employed the help of Walter Mayo Macomber during their search. As the resident chief architect for the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, Macomber was well versed in researching and restoring historic homes. After traversing the Eastern seaboard looking at options, the three eventually ended up in Danvers, Massachusetts in August 1934; "We found The Lindens was for sale at the same time," recalled Macomber in 1982.5 By that point, the house was in a poor state, and was missing its paneled drawing room, which had been bought earlier by antiques dealer Israel Sacks and subsequently sold to the Kansas City Museum. Yet this did not stop the Morrises from falling in love with the property. Given the poor condition of the home, they purchased it for only $14,000 ($334,732 in 2025).6 Now that the couple had found their forever home, the real dilemma began: how would they get it back to Washington? This is where Macomber’s expertise came in.

In order to move The Lindens, every inch of the home would need to be dismantled, numbered, and boxed. Macomber supervised a large team, removing walls, doors, French linen wallpaper, and the home’s 11 fireplaces. "Fortunately, there was a lull then at Williamsburg, so I was able to get carpenters and other craftsmen I'd trained to do the work,” Macomber told The Washington Post later, “It helped that much of the trim was mortised and tenoned. We could knock out the old pegs. We also saved 10 or 15 pounds of handmade nails. We took the doors and its frames off in one piece. Upstairs, by one door, we found a child's handprint, pressed into the original plaster. I carefully cut it out and when we replastered, we set it in the same place."7 After seven weeks of work, the pieces of The Lindens were loaded into boxcars and freighted down to Washington.

As news began to spread of this historic move, newspapers in the District wrote up stories informing residents of The Lindens’ history, as well as the Morrises' plan to resettle the structure. The Evening Star wrote in September 1934 that “The reconstruction here of the Lindens will add to the National Capital, it is said, perhaps the purest example of colonial architecture in the city and will give Washington a historic house older than the Capital itself.”8 In another article, the Star referred to the project as an “architectural jig-saw puzzle,” adding that “when the work of piecing together the house is finished it will look to passersby as it did to travelers in Massachusetts a century and a half ago.”9 Despite the fanfare, by the time the home arrived in Washington in 1935, there was still a lot of work to do. While the Morrises aimed at keeping the home as original as possible, they chose to add a few modern conveniences. Chief among such projects would be the addition of 10 bathrooms, a hard feat given the age and layout of The Lindens. However, Macomber discovered that the chimneys ran the whole height of the house, and featured small closets on either side in each room. He decided to repurpose these closets into the bathrooms.10 Also changed was the lighting. In an effort to combine antique authenticity and modern convenience, Macomber had the home entirely lit by electrified wax candles. This technique was first used at the Winterthur Museum, which houses the richest collection of American decorative arts in the country. Wax candles would be hardened with resin and hollowed out to feed electric wires through. A socket would be installed at the top with a flamelike bulb placed inside. Within the nearly 9,000 square foot home, the library was the only room that contained modern table lamps.11 By 1937, The Lindens was finished, rebuilt in exactly the same manner as it was when it stood on Sylvan Street in Danvers, save for Macomber’s additions, a new concrete foundation, and steel support beams. With their masterpiece complete, the Morrises set about living their colonial dream.

George and Miriam, eager to share both their new home and historic furnishings with the general public, hosted a house warming reception on November 26th, 1937. In keeping with the theme of their home, invitations were “printed in old English script on reproductions of eighteenth century paper.”12 Although this event was not open to the public, it would be the start of 51 years of sharing their home and collection with almost 60,000 visitors.

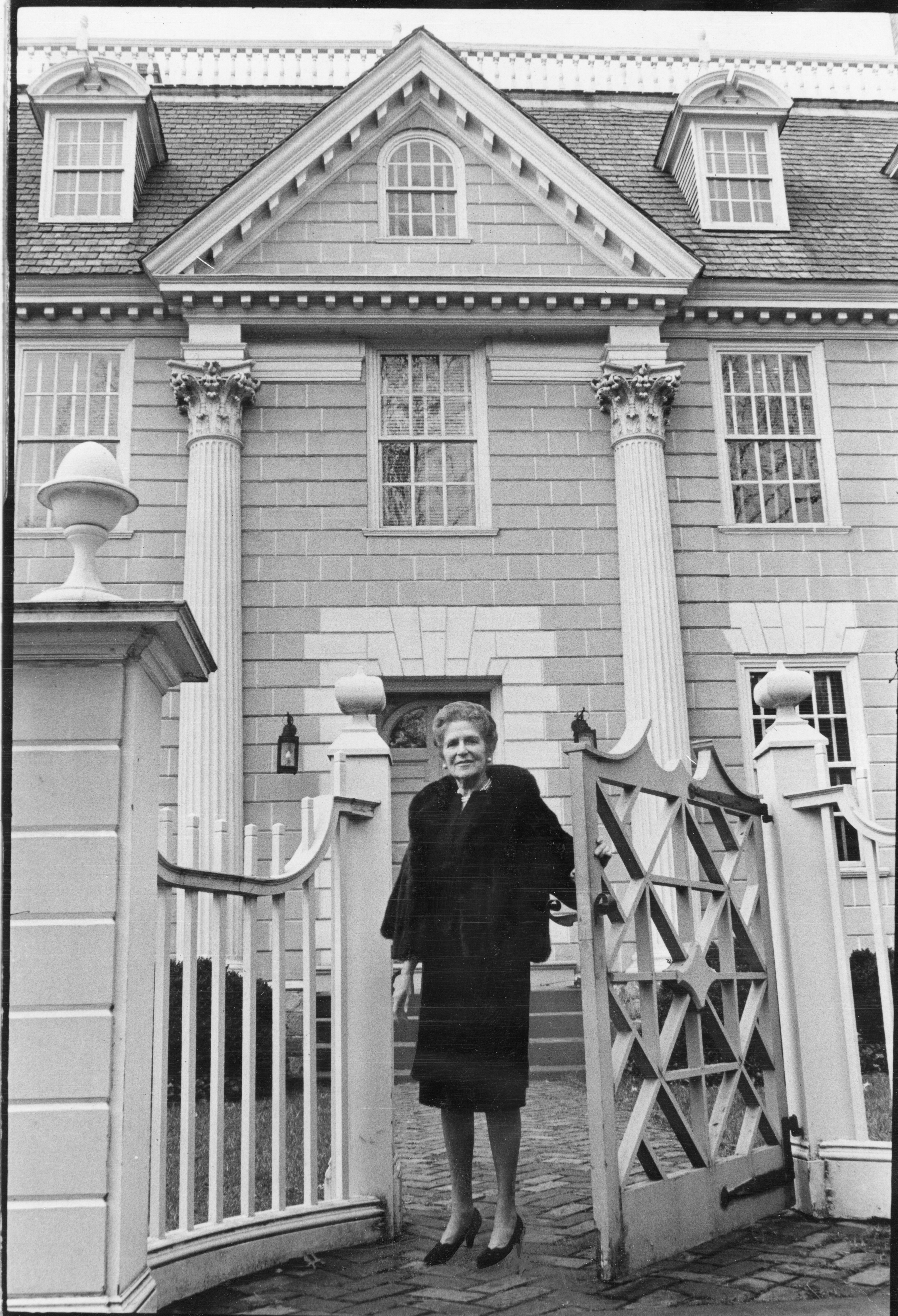

While there were days in which the home was opened up to the public, most guests at The Lindens, however, were more than just your average D.C resident. In 1941, the day before Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated to his third term as president, the Morrises hosted an inauguration party at their home. In attendance were Washington socialites, foreign dignitaries, and most notably, Archduke Otto von Hapsburg, the last Crown Prince of Austria-Hungary.13 In December 1949, a dinner hosted by the Morrises included French Ambassador to the United States Henri Bonnet, Italian Ambassador to the United States Alberto Tarchiani, as well as John Jay, the official photographer for the 1948 Olympic Winter Games.14 Even after George Morris's death in 1954, Miriam continued to host lavish dinner parties, offering visitors a chance to step back in time. One guest at a party in 1956, put on to celebrate the home’s 202nd birthday, described the scene as a “200-year old flashback”;

Dressed up for the party, the exterior of The Lindens was like an 18th century painting. With candles burning in every window, the handsome mansion, now Washington’s oldest, glowed with elegance. The footman was clad in Colonial livery, lace ruffles, a navy-blue coat and velvet knee breeches. There’s nothing visible at The Lindens that’s not 18th century…In the hall, Harpist Jeanne Chaifoux of the National Symphony Orchestra strummed 18th-century rhythms in her colonial dress. Downstairs in the early American room guests sampled the Fish House punch and an 18th-century supper authenticated by Helen Bullock, author of the cookbook for Colonial Williamsburg.15

Mrs. Morris would continue life as usual in the home until her death at age 90 in 1982. One year later, her collection of early American furniture would go to auction at Christies, where it amassed a total sale value of $2.3 million. That same year Norman Bernstein, a Washington real estate developer, and his wife Dianne purchased the home, updating its kitchen and plumbing while still keeping its historic charm. The Lindens' most recent sale was in 2016, where it sold for $7.1 million to an unknown buyer for use as a private residence. The Lindens has had quite a history. Born in New England, there is no doubt that this masterpiece of American architecture will outlive all of us here in Washington.

Footnotes

- 1

Taylor, Nancy C. “The Lindens or King Hooper House, Washington, District of Columbia.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. National Capital Planning Commision, District of Columbia, June 4, 1969. P.2

- 2

Ibid

- 3

Conroy, Sarah Booth. "Lovely Lindens."The Washington Post, June 14, 1982.

- 4

Ibid

- 5

Ibid

- 6

Ibid

- 7

Ibid

- 8

The Evening Star, "Historic Massachusetts Home Will Be Moved To Washington." September 11, 1934, sec. Society.

- 9

The Evening Star,"Rebuilding of Historic Home Called Feat of Architecture." November 16, 1935, sec. Real Estate.

- 10

Dietz, Paula. "Uncertain Future For 1754 Mansion."The New York Times, September 2, 1982, National edition, sec. C.

- 11

Ibid

- 12

The Evening Star, "Mr. and Mrs. George M. Morris Plan Series of Receptions." November 10, 1937, sec. Society.

- 13

The Evening Star, "Non-Inaugural' Parties Share in Social News Over the Week End." January 19, 1941, sec. Society.

- 14

The Evening Star,"Mr., Mrs. Morris Hosts At Dinner." February 27, 1949.

- 15

Beale, Betty. "The Lindens Mark 202nd Anniversary."The Evening Star, December 3, 1956, sec. Society.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)