Washington's Irish Roots Include Matilda Tone, a Forgotten Hero of Irish Nationalism

On St. Patrick’s Day Washingtonians would do well to remember their city was once home to one of the most influential and underappreciated figures in the push to establish an independent Irish republic—Matilda Tone. The widow of Irish rebel Theobald Wolfe Tone, Matilda spent thirty years living in Georgetown, where she compiled and edited her martyred husband’s papers into a book that would grow to become the “sacred scripture” of Irish nationalism after its 1826 publication in D.C.1

While Boston, Philadelphia, or Chicago might be more often associated with Irish-American culture, Irish identity and history runs deep in Washington’s DNA, even before Matilda moved to the capital city in the late 1810s. In fact, some of D.C.’s most iconic buildings have their roots in the Emerald Isle.

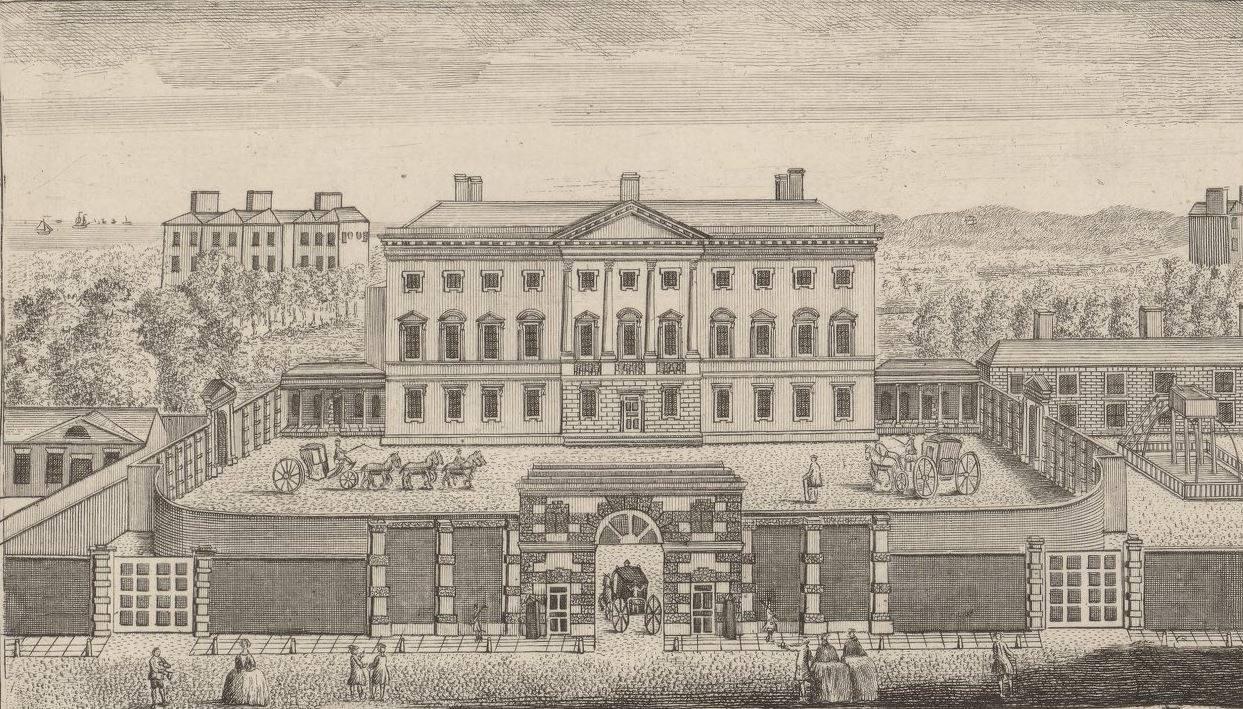

The White House itself was designed by James Hoban, an architect born in County Kilkenny who emigrated to the U.S. in 1785 and eventually settled in Charleston, South Carolina, where he met George Washington during the president’s Southern Tour of 1791.2 Impressed by Hoban’s work, Washington invited the Irishman to submit a proposal for the yet-to-be built executive mansion as part of a public competition.

Selected by Washington, Hoban’s design drew inspiration from the Leinster House, a 1745 Georgian palace in Dublin that today host’s Ireland’s parliament, the Oireachtas.3 Hogan oversaw construction of the White House—which employed Ben, Daniel, and Peter, three enslaved carpenters owned by the architect—along with the fledgling Treasury and War Department and the U.S. Capitol Building.4

Hoban’s influence extended beyond neoclassical federal buildings, as the proud Catholic also designed a number of churches and hotels and helped fund the establishment of Georgetown University in the early 1790s.5 Founded as a colonial tobacco trading port in 1751, the Jesuit university’s namesake also hosted Washington’s earliest Irish community, many of whom lived near the town’s rapidly industrializing waterfront.

Beginning in the 1820s, Irish laborers assisted with the building of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, a project the canal’s stockholders believed would turn Georgetown and the surrounding areas into a “commercial place, second in rank only to some of the largest in the United States.”6 Wealthier Irish immigrants, including future Georgetown mayor Thomas Corcoran, settled farther north of the river and some, including Hoban, married into the neighborhood’s other well-to-do families.7

Across the Potomac from Georgetown, Alexandria—which remained part of the District until its retrocession to Virginia in 1847—also developed its own thriving Irish community. Irish cultural associations like the Hibernian Society held raucous meetings and lectures, some delivered by prominent non-Irish locals that also championed Irish independence.

Most prominent among these allies was George Washington Parke Custis, a wealthy Arlington planter, enslaver, author, and step-grandson of George Washington, who gave numerous speeches over the course of his life in support of Irish civil and religious liberties that earned him the title of “The Friend and Orator of Ireland” from local Irish groups.8

For one St. Patrick’s Day speech in 1829, the 48-year-old Custis donned a green coat, placed a shamrock in his hat, and delivered an animated talk praising Irish patriots that served in the American Revolution and comparing the earlier war to Ireland’s ongoing struggle for political freedom.

“Brunswick Americans will say, what have we to do with the rights of Irishmen, or whether they are entitled to any rights at all—what have a Protestant people to do with the emancipation of Catholics,” said Custis, who rhetorically asked the largely Irish Catholic crowd: “I answer, what had the Irish patriots, statesmen and soldiers of American liberty, to do with the rights of Americans in 1775?”9

Matilda Tone and her family joined this burgeoning Washington Irish community in 1819 after a tumultuous few decades.10 Born Martha Witherington in 1769, the Dublin native married then-Trinity College law student Theobald Wolfe Tone, who nicknamed his 16-year-old bride after a character in one of his favorite historical dramas.11 Although born into a Protestant, Anglo-Irish family, Wolfe Tone was radicalized by the French Revolution and soon published pamphlets calling for Catholic emancipation, co-founded the revolutionary group United Irishmen, and avoided imprisonment by exiling himself and his young family to America in 1795.12

The couple loathed their new country, with Wolfe Tone describing New Jersey farmers as “boorish and ignorant,” Philadelphia residents as “a churlish, unsocial race, totally absorbed in making money,” and even proclaiming he’d rather see his daughter Maria dead than in the arms of an American husband.13 He decried George Washington as a “high-flying aristocrat,” railing against the president’s federalist and anti-French policies in letters to other United Irishmen.14

In early 1796 a restless Wolfe Tone sailed for Paris to lobby for a French invasion of Ireland to help overthrow the British, leaving behind Matilda and their three children.15 The family reunited in France in 1797, but the next year British forces captured Tone off the coast of Donegal as his French task force attempted to assist a fizzling Irish rebellion. Court-martialed and sentenced to hang, the lawyer-turned-rebel died in a Dublin prison on November 19, 1798, after a failed suicide attempt.16

Her husband’s death left Matilda and children Maria, Francis, and William in a precarious and impoverished state. Maria and Francis died of tuberculosis in 1803 and 1806, respectively, and the French government delayed payment of a military pension.17 In 1816 Matilda remarried Thomas Wilson, a Scottish radical and longtime friend, and the two attempted to return to Ireland but were barred entry by British officials, who feared Matilda’s presence would stir nationalist sentiment again.18

Exiled from her homeland, Matilda Tone-Wilson embarked on her second stint in America in 1817, first moving to New York before joining surviving son William, who had moved to Georgetown after earning a commission in the U.S. Army.19 Included in her luggage were piles of Wolfe Tone’s published and unpublished papers, including diaries, letters, autobiographical sketches, and political memorabilia. Additional papers had been entrusted to Irish-born physician James Reynolds during the Tone’s initial stay in the U.S., but when visiting the doctor in 1807 Matilda and William discovered Reynolds had lost or sold most of his materials, some of which were later recovered.20

Matilda had long considered publishing her first husband’s works, writing to her sister Catherine Heavyside in 1814 that “They will certainly appear, but not yet, not till they become purely historical, till the world is calm and people have had time to feel, and it shall never be done for profit, nor from any hostile feeling to any living creature.”21

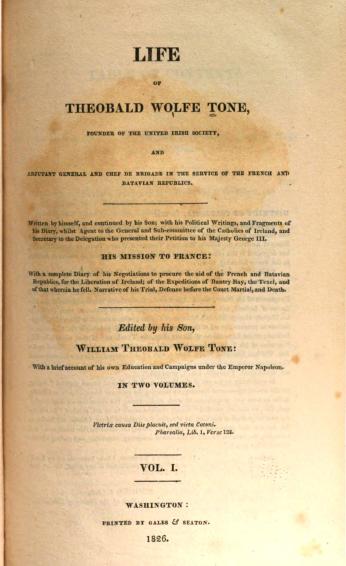

The catalyst came in 1824, the year her second husband Wilson died and the London journal New Monthly Magazine released unauthorized excerpts of Wolfe Tone’s autobiography that incensed Matilda.22 Determined to set the record straight, she and William began editing the papers, their mammoth undertaking resulting in the 1,200 page, two-volume Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, published by Gales and Seaton of Washington in 1826.23 Ads for the book appeared near weekly in Alexandria’s Phenix Gazette that spring, noting a hefty price of $6 for the full set.24

As Wolfe Tone scholar Marianne Elliott writes, the book eventually “formed the basis of the cult which by the twentieth century had turned Tone into the most influential inspiration of modern Irish nationalism and republicanism.”25 Frequently cited by future revolutionaries like Easter Rising leader Patrick Pearse, the writings displayed Wolfe Tone’s uncommon frankness and wit—excluding his earlier tirades on America and George Washington, which were dutifully edited out.

Although only William was listed as an editor in the first edition, historians have recently started to give Matilda her due credit for her work molding the seminal book that shaped Irish nationalist discourse over the next two centuries. Especially after William died of “an intestinal disorder” in Georgetown in 1828, Matilda continued promoting Wolfe Tone’s legacy in letters and meetings with other Irish exiles.26

In March 1849 while visiting the States to promote Irish independence, Young Ireland activist Charles Hart decided to try and pay the then 79-year-old Matilda a visit. Walking west to Georgetown after attending the inauguration of Zachary Taylor, Hart was ushered into the library of a “fine old house” on First Street, today’s N Street NW, where the widow lived.27

Still “beautifully smooth and fair” at nearly 80 years old, Matilda had a “nose straight, perhaps a little thick; under lip slightly projecting, eyes full of light, as was her whole face,” as described by Hart, who noted her pleasing Dublin accent.28 Matilda “chatted very gaily” about her old life in Ireland, expressing regret she had never visited again and begging Hart not to “expatriate yourself” as she had.29

“Here I am for thirty years in this country and I have never had an easy hour, longing after my native land,” reflected Matilda, who said of Ireland, “I have been for the best part of my life, and I can tell you I am not very young, hoping and watching for something to turn up for that country, but I am afraid that now there is no hope, it’s too small.”30

Just two weeks later on March 18, 1849, Matilda died in Georgetown and was buried next to William at the Marbury Cemetery.31 After Marbury’s sale, their remains were reinterred in 1891 at Brooklyn, New York’s Green-Wood Cemetery, which would host future ceremonies in honor of her service to Irish republicanism.32

Despite Matilda’s pessimism, Hart walked away from their interview realizing for the first time “what a heroine [Wolfe Tone’s] wife was.”33 He would not be the only one, and today the longtime Georgetown resident’s name is finally being included in discussions of the greatest Irish nationalist heroes.

Author's note: Unfortunately, portraits of Matilda Tone are hard to come by though you can find one — and photos of her grave — on the Fenian Graves Association website.

Footnotes

- 1

James Quinn, “Theobald Wolfe Tone and the Historians,” Irish Historical Studies 32, no. 125 (May 2000): 114.

- 2

“The story of James Hoban: The Irishman who built the White House,” EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum, https://epicchq.com/story/the-story-of-james-hoban-the-irishman-who-built-the-white-house/.

- 3

“The story of James Hoban: The Irishman who built the White House,” EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum, https://epicchq.com/story/the-story-of-james-hoban-the-irishman-who-built-the-white-house/.

- 4

“James Hoban Slave Payroll," National Archives and Records Administration, The White House Historical Association, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/photo-2-4.

- 5

“The story of James Hoban: The Irishman who built the White House,” EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum, https://epicchq.com/story/the-story-of-james-hoban-the-irishman-who-built-the-white-house/.

- 6

“Chesapeake and Ohio Canal,” Alexandria Gazette, 12 September, 1828

- 7

Robert Benedetto, Historical Dictionary of Washington, D.C. (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003).

- 8

“Speech Of Mr. Custis, of Arlington, at the O’Connell Celebration, at Washington, on the 6th of August, 1832,” Phenix Gazette, 22 August, 1832.

- 9

“Speech Of Mr. Custis, of Arlington, at the O’Connell Celebration, at Washington, on the 6th of August, 1832,” Phenix Gazette, 22 August, 1832.

- 10

David Brundage, “Matilda Tone in America: Exile, Gender, and Memory in the Making of Irish Republican Nationalism,” New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, 14, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 104.

- 11

Brundage, 102.

- 12

Brundage, 102.

- 13

Marianne Elliott, Wolfe Tone: Prophet of Irish Independence (New Haven, 1989); Brundage, 103.

- 14

T. W. Moody, R. B. McDowell, and C. J. Woods (eds), The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone, 1763–98 (3 vols, Oxford, 1998), 12.

- 15

Brundage, 103.

- 16

Elliot, 398.

- 17

Elliot, 403-404.

- 18

C.J. Woods, “Tone, Matilda (Martha),” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/tone-matilda-martha-a8588.

- 19

C.J. Woods, “Tone, Matilda (Martha),” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/tone-matilda-martha-a8588.

- 20

Brundage, 104.

- 21

Matilda Tone to Catherine Heaviside, 10 December, 1814 (RIA, MS 23/K/53) in C.J. Woods, “Tone, Matilda (Martha),” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/tone-matilda-martha-a8588.

- 22

Brundage, 104.

- 23

Brundage, 105.

- 24

See “Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone,” Phenix Gazette, 15 April, 1826

- 25

Marianne Elliott, “Tone, (Theobald) Wolfe,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, January 3, 2008, https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-27532.

- 26

C.J. Woods, “Tone, William Theobald Wolfe,” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/tone-william-theobald-wolfe-a8592.

- 27

Charles Hart, Young Inlander Abroad: The Diary of Charles Hart, ed. Brendan O Cathaoir (Cork: Cork University Press, 2003), 62.

- 28

Hart, 62.

- 29

Hart, 62.

- 30

Hart, 62.

- 31

C.J. Woods, “Tone, Matilda (Martha),” Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/tone-matilda-martha-a8588.

- 32

Brundage, 96.

- 33

Hart, 62.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)