The Gruesome Murder Spree of the "Freeway Phantom": D.C.'s First Serial Killer

In early May 1971, chaos embroiled Washington, D.C. The infamous May Day protests gathered members of the anti-Vietnam War movement who were dissatisfied with the marches of years past.1 Groups of protesters blocked major intersections and bridges, chanting the slogan, “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.”2 The government responded in kind, arresting 12,000 people across the city, the largest mass arrest in American history.3 Yet beneath the surface of anti-war tension, a far more nefarious terror was building, one that has haunted the capital for the past 53 years. On the evening of Sunday April 25, a teenage girl went missing. Sadly, no one knew it then, but she was the victim of D.C.’s first serial killer, a man who came to be known as the Freeway Phantom.

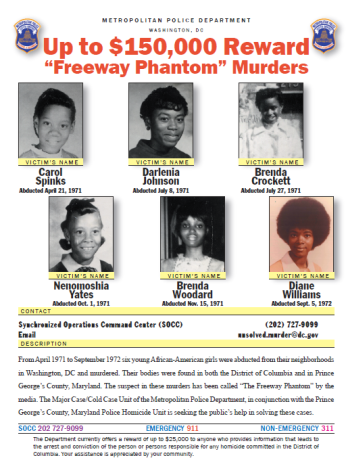

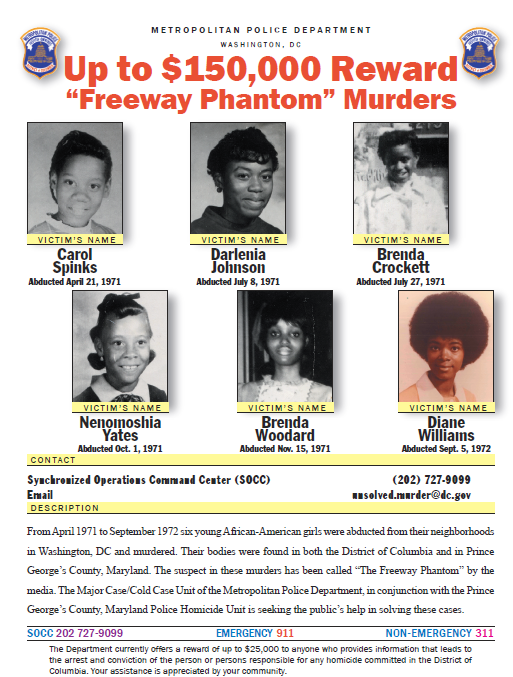

Thirteen-year-old Carol Spinks was one of eight children being raised by single mother Allenteen Van Thompson Reeves in Southeast D.C. On that fateful day, Carol left home to go to the nearby 7-Eleven. A half hour later, she failed to return, to the alarm of her siblings and mother. Reeves called the police, who gave a standard but less than comforting response: “She ran away from home.” Carol enjoyed a close relationship with her family, who knew that she would never run away. Reeves formed a search party with her friends and neighbors, but to no avail. The family knew something was very wrong. Six days later, on May 1, their worst fears were confirmed.4

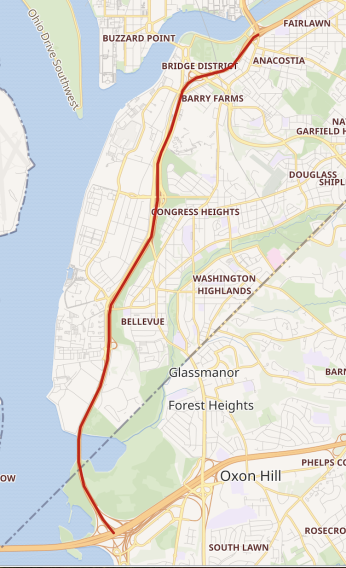

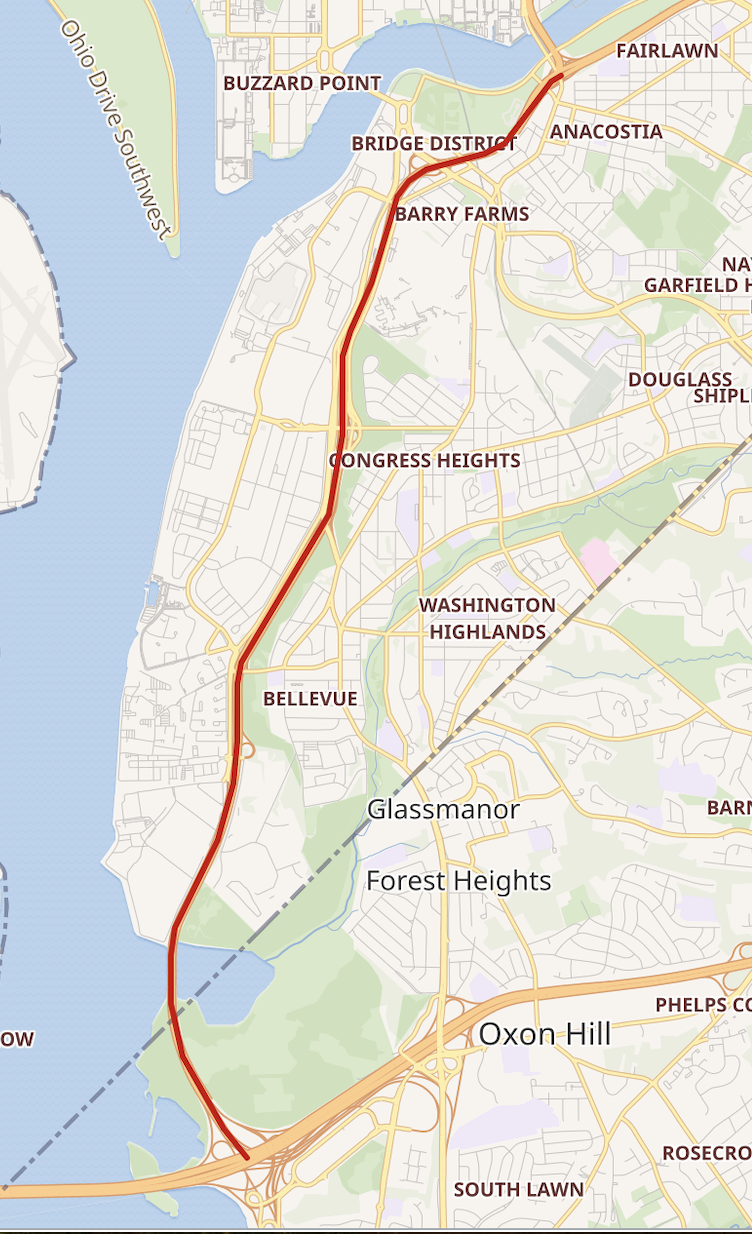

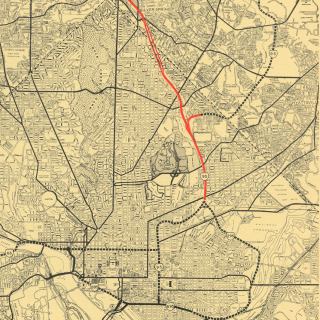

The police discovered Carol Spinks’ body behind St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, near I-295.5 Homicide detectives delivered the news to Reeves. The coroner’s report was horrific. Carol was sexually assaulted and strangled. Two curious details alarmed investigators. Carol’s shoes were missing, possibly taken as trophies. Undigested food was found in her stomach, confirming she was alive for much of the six-day period she was missing, and fed.6 Carol’s family was left to imagine what she endured during her captivity.

The D.C. Metro police remained vigilant for leads, but Carol’s unsolved murder could hardly have occurred at a worse time. Anti-war protesters flooded the city, overwhelming the police and local jails. So many thousands of people were arrested that makeshift camps had to be constructed around the city to detain them. Every available officer in D.C. was called for emergency duty. Retired homicide detective Romaine Jenkins remembers what happened when she tried to investigate Carol’s murder amid the protests. “I was going out, and the division commander stopped me. He said, ‘Where are you going?’ I said, ‘I’m going to do some follow-up on the case of the little girl found in Southeast.’ And he said, ‘No. The whole department is on prisoner alert. That includes the homicide squad.’ And so, I couldn’t go.”7

Carol’s family was infuriated at the police’s lack of a response. “If this happened to my sister, it could happen to anybody,” said Carol’s older sister Evander Spinks-Belk. “And it did.”8

Darlenia Johnson lived in the same neighborhood as the Spinks in Southeast D.C. On the morning of July 8, the 16-year-old left home to go to her summer job. She never showed up. Darlenia’s mother Helen filed a missing persons report. But this disappearance would unfold differently for her than the Spinks. Over the next two weeks, someone called Helen’s home, never speaking, just breathing into the phone. That is until the final call, when a man on the line said, “I killed your daughter.” He then hung up.

Helen reported this to the police, but they lacked the technology to trace the call. On July 19, a police officer discovered the body of a young girl on the roadside of I-295. She had been decomposing under the July sun for two weeks, making facial identification impossible. Based on clothing found on the body, police confirmed the victim to be Darlenia Johnson. Police couldn’t determine her cause of death due to her advanced state of decomposition, but they believed Darlenia was murdered because she was found just fifteen feet from where Carol Spinks’ body was found two months earlier.9

With the death of a second victim, Evander Spinks-Belk felt assured that police would find out more about her sister’s killer.10 But before the police could make any head way, just eight days after Darlenia Johnson’s body was discovered, another young girl was reported missing, this time in Northwest D.C. On the evening of July 27, 10-year-old Brenda Crockett failed to return home by dark, after having been sent to the grocery store by her mother, just a block and a half away from their home. Her mother went looking for her after dark, leaving Brenda’s 7-year-old sister Bertha home with their stepfather. The phone rang. Bertha answered and heard her sister on the other end of the line.11

“Brenda told me that a white man had picked her up, and they were gonna send her home in a cab.” The call ended, but the phone rang again a few minutes later. Brenda was on the line again, but this time her stepfather picked up the phone. Brenda told her stepfather she was in Virginia. “She was crying. She was confused and didn’t really know what was about to happen to her.” Brenda, or whoever else was on the other end of the line, hung up. Brenda’s mother returned home and heard the story. She called the police, who came to their home and questioned Bertha. “The next morning, I woke up to the most horrific scream. My mom had found out that my sister had been found.”12 On July 28, a hitchhiker found Brenda Crockett’s lifeless body along the U.S. Route 50 near the Baltimore-Washington Parkway in Prince George’s County, Maryland. As with the previous two victims, she had been sexually assaulted and strangled.13

Detectives speculated that the calls were scripted, with inaccurate information fed to throw the investigation off. Following that theory, they surmised that the killer probably wasn’t a white man, nor was Brenda in Virginia. As with Darlenia Johnson, police could not trace the calls. After the third victim, news reporters flocked to Spinks’ and Johnson’s neighborhood, conducting their own investigations. “The news would tell you more than the police would tell you,” remembers Carol Spinks’ sister Evander.14

A pattern was emerging. On October 1, a fourth young girl was abducted in Northeast D.C. In an eerie repeat of the first and third abductions, 12-year-old Nenomoshia Yates was sent to a Safeway by her father, just one block away from her home. Witnesses saw her purchasing the items and leaving the store, but no one saw what happened next. Less than three hours later, on the shoulder of Pennsylvania Avenue in Prince George’s County, Nenomoshia’s body was found. Again, she had been sexually assaulted, strangled, and her shoes were missing.15

After news of a fourth young girl being kidnapped and murdered spread, the Southeast community broke into a panic. “The neighborhood felt like it was all connected,” remembered Evander Spinks-Belk. “It had to be.”16 Anger rose towards the police for their lack of progress, fueled by fear and a burning desire for answers. Questions from the media of what was going on, and what police were doing about the murders echoed across frantic newspaper headlines. Local media believed that the murders were the work of a single killer, who was using the I-295 highway to hunt his victims and escape, due to the bodies all having been found so close to the highway. This theory resulted in the Daily News dubbing the killer the “Freeway Phantom”.17 But the police weren’t yet convinced that the murders were all connected. Neither did the police department have a forensics lab as developed as it does today. As panic in the District grew, the FBI formed a joint task force with the police to assist the investigation forensically, and begin looking into the murders collectively.

Police and the FBI re-examined evidence from the victims’ bodies. Investigators found hairs belonging to an African-American in the underwear of three victims, hairs that didn’t belong to them. The police determined the four murders were likely to have been committed by the same individual, most likely a black male.18 “These were probably the first serial cases in the District of Columbia that one can recall,” said detective Romaine Jenkins.19

As if things couldn’t get any worse, a fifth girl went missing. On November 16, a police officer found the body of 18-year-old Brenda Woodard along an access ramp to the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, near Prince George’s County Hospital. Her death followed the modus operandi of the Phantom’s other victims, except she was also stabbed. Other unusual details steered away from the killer’s other crime scenes. A velvet coat had been laid over Woodard’s body. Police pulled a handwritten note out of a coat pocket. The note read:

“this is tAntAmount to to my

insensititivity [sic] to people

especially women.

I will Admit the others

whEn you cAtch me iF you cAn!

FRee -WAY PhanTom!”20

“I was scared for me, and every other little girl after that,” said Brenda Crockett’s sister Bertha. “Everybody was phoning in suspects to the police department,” said Jenkins. “We were looking at priests, police officers, doctors … Every male that you could think of ended up being a suspect at one time.”21

But just as the investigation was heating up, the murders stopped. Perhaps the FBI’s involvement and increased media attention spooked the Phantom into ceasing his killing spree. But not forever. Ten months after Brenda Woodard’s murder, on September 5, 1972, 17-year-old Diane Williams failed to return home from a visit to her boyfriend’s house in Southeast D.C.22 “I remember the night that she didn’t come home,” said her sister Patricia Williams, “how hard it was for me to go to sleep.” Police found her body near I-295 the next morning. “From that moment on, our lives were never the same.”23 Diane Williams was strangled, but she was not sexually assaulted, nor were her shoes missing.

Detectives tried to connect known sexual predators to the slayings. In 1974, police received a tip from convicted rapist Morris Warren, a Virginia prison inmate who claimed to have known the identity of the Freeway Phantom. FBI took him on ride-alongs to test his credibility, but Warren’s details were full of inconsistencies. His credibility evaporated when letters written by Warren were intercepted, where he admitted to lying to the police, hoping to get released from prison in exchange for information on the Phantom.24

Without any suspects or viable leads, time passed, other cases took precedence, and the Freeway Phantom cases faded into obscurity. The joint task force dissolved. But the Phantom continued to haunt his victims’ families and investigators. “You never lost interest in this case,” said retired FBI agent Barry Colvert, who worked on the task force. “What you had seen, and what you had learned about the deaths of these girls, was so upsetting. Oftentimes I would try and make sense out of what this was. What had happened to that person to make him hate so much, that the only way to make that hate go away, is to watch some little girl die in front of him. That was very, very hard for me to live with.”25 The D.C. police department’s reputation was tarnished by the fact that the cases remained unsolved.

Then, in 1987, detective Romaine Jenkins was promoted to sergeant, and was finally able to make solving the Phantom cases a top priority for the police department. She re-opened an investigation, starting by searching for the case files and forensic evidence. But Sergeant Jenkins made a shocking and tragic discovery.

In a breach of protocol and a lack of forward-thinking, detectives destroyed forensic evidence and case files, and lost many materials in a warehouse. “The police came to our house and took all my sister’s clothes, her pictures, everything,” remembered Evander Spinks-Belk about the days after her sister was murdered. “And now, it’s gone!”26 Detectives mistakenly believed the Phantom cases were obsolete.

Sergeant Jenkins was enraged. But with help from the FBI and other detectives from the cases, Jenkins was able to reconstruct the destroyed case files. The evidence, though, will likely never be recovered.

Under the renewed focus on the case, FBI crime analysts completed a behavioral profile of the Freeway Phantom in 1990, based on old materials from the investigation and conversations with investigators from the cases. He was likely a misogynistic psychopath, between the ages of 27 and 32 at the time of the murders. Some of his victims may have even known him, and apparently trusted him enough to get into his car, if that’s how they were abducted. The killer may have lived or worked in Southeast D.C.

But no arrest has ever been made. Sergeant Romaine Jenkins retired in 1994, disappointed she couldn’t find all the pieces to solve the puzzle of the Freeway Phantom. All that could happen now is for new information to come to light, hopefully through people coming forward to the police. As a result of the accidental destruction of the evidence, and the D.C. police department’s embarrassment over it, the city council mandated that evidence in unsolved homicide cases be preserved for a minimum of 65 years.27

Diane Williams would be the Freeway Phantom’s sixth, and presumably final murder. His reign of terror never ended for the victims’ families. Carol Spinks’ mother Allenteen passed away in 1992. With the lack of progress in the investigation and the loss of evidence, the families never believed the police were doing everything they could to solve the cases. “You never forget. There is no closure,” said Diane’s sister Patricia Williams. “Whoever did it has gotten away. They may be living somewhere else, doing it again.28

Footnotes

- 1 Time. “Order of Battle - TIME.” May 10, 1971. February 3 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080203122947/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,902933,00.html.

- 2 Georgetown University Library. “The Most Influential Protest You’ve Never Heard Of: May Day, 1971 | Georgetown University Library,” April 26, 2021. https://library.georgetown.edu/exhibition/most-influential-protest-you%E2%80%99ve-never-heard-may-day-1971.

- 3 Roberts, Lawrence. Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest. HarperCollins, 2020.

- 4 Thompson, Emily G. Unsolved Child Murders: Eighteen American Cases, 1956-1998. Exposit Books, 2017.

- 5 Metropolitan Police Washington, D.C. “‘Freeway Phantom’ Homicide Victims,” n.d. https://mpdc.dc.gov/publication/%E2%80%9Cfreeway-phantom%E2%80%9D-homicide-victims.

- 6 “Cases 121: The Freeway Phantom.” Casefile True Crime, n.d. https://audioboom.com/posts/7344591-case-121-the-freeway-phantom.

- 7 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 8 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 9 Thompson, Emily G. Unsolved Child Murders: Eighteen American Cases, 1956-1998. Exposit Books, 2017.

- 10 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 11 “Cases 121: The Freeway Phantom.” Casefile True Crime, n.d. https://audioboom.com/posts/7344591-case-121-the-freeway-phantom.

- 12 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 13 Metropolitan Police Washington, D.C. “‘Freeway Phantom’ Homicide Victims,” n.d. https://mpdc.dc.gov/publication/%E2%80%9Cfreeway-phantom%E2%80%9D-homicide-victims.

- 14 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 15 “Cases 121: The Freeway Phantom.” Casefile True Crime, n.d. https://audioboom.com/posts/7344591-case-121-the-freeway-phantom.

- 16 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 17 Quentin Wilber, Del. “‘Freeway Phantom’ Slayings Haunt Police, Families.” The Washington Post, June 25, 2006. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2006/06/26/freeway-phantom-slayings-haunt-police-families-span-classbankheadsix-young-dc-females-vanished-in-the-70sspan/08789f47-3d0e-4a88-ad24-cdbcc493698f/.

- 18 Smith, Rend. “Mysteriously Missing FBI Report Could Have Helped Solve the Freeway Phantom Cold Case Murders.” Washington City Paper, May 9, 2024. http://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/694427/mysteriously-missing-fbi-report-could-have-helped-solve-the-freeway-phantom-cold-case-murders/.

- 19 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 20 Chau, Eddie. “Solving Cold Cases One Letter at a Time.” Toronto Sun, December 25, 2021. https://torontosun.com/news/world/solving-cold-cases-one-letter-at-a-time.

- 21 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 22 Thompson, Cheryl W. “Six Black Girls Were Brutally Murdered in the Early ’70s. Why Was This Case Never Solved?” Washington Post, May 22, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/six-black-girls-were-brutally-murdered-in-the-early-70s-why-was-this-case-never-solved/2018/05/21/c74d26ec-4e22-11e8-af46-b1d6dc0d9bfe_story.html.

- 23 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 24 Pardoe, Blaine L. “Freeway Phantom.” Tantamount, n.d. https://blainepardoe.wordpress.com/tag/freeway-phantom/.

- 25 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 26 “People Magazine Investigates.” Documentary. The Freeway Phantom. Investigation Discovery, November 25, 2019.

- 27 Thompson, Cheryl W. “Six Black Girls Were Brutally Murdered in the Early ’70s. Why Was This Case Never Solved?” Washington Post, May 22, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/six-black-girls-were-brutally-murdered-in-the-early-70s-why-was-this-case-never-solved/2018/05/21/c74d26ec-4e22-11e8-af46-b1d6dc0d9bfe_story.html.

- 28 Fountain, John W. “KILLINGS UNSOLVED 25 YEARS LATER.” The Washington Post, September 19, 1997. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1997/09/20/killings-unsolved-25-years-later/4c921bb7-5d9d-4752-99f2-0bd00d6ca0df/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)