Washington Reacts to the Sinking of the Lusitania

On the morning of May 1, 1915 Washington Post subscribers opened their morning newspapers and found a stern message from the Imperial German Embassy on Massachusetts Avenue.

“Travelers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notices given by the imperial German government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or of any of her allies are liable to destruction in these waters and that travelers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.”[1]

The same warning was printed in papers all across the United States – a harbinger of things to come as World War I raged in Europe.

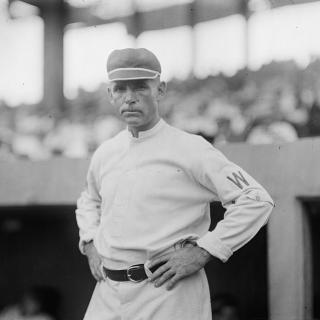

It’s likely that prominent Washington physician Dr. Howard Lowrie Fisher had read the Embassy’s release when he and his sister-in-law, Dorothy Conner of Oregon, boarded the luxurious RMS Lusitania in New York that morning. If he did, he may have been reassured by the ship’s captain, William Turner, who boldly claimed that the powerful ocean liner was too fast for Germany’s U-boats to pose a threat.

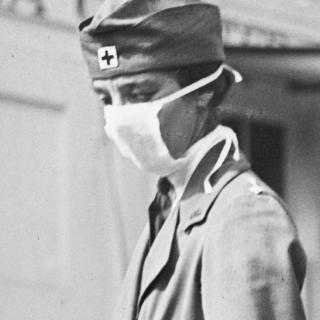

In any case, Fisher knew what he was getting into better than most. The United States was not yet in the war but the doctor was crossing the Atlantic to aid his brother-in-law, prominent Englishman Harold J. Reckitt, in organizing a hospital unit on the battlefields of France. As Reckitt recounted in his history of the hospital, “The dangers of ocean traffic as it approached English waters were beginning to be felt and we on this side wired to suggest that the Lusitania would be the safest vessel to choose” for Fisher’s journey.

For several days, it probably seemed that way. Departing New York for Liverpool, the trip was uneventful, even boring according to Dorothy Conner, who wrote to her mother that she couldn’t have taken a “more uneventful or stupid voyage.”[2] (See video of the ship's boarding and launch on May 1.)

That all changed in the early afternoon of May 7, when German U-boat U-20 spied the ship through its periscope off the coast of Ireland. As Fisher and Conner were enjoying a late lunch with companions, submarine captain Walther Schwieger gave the order to fire.

Schwieger later detailed the attack in his diary: “Clear bow shot at 700 [meters]…. Shot struck starboard side close behind the bridge. An extraordinarily heavy detonation followed, with a very large cloud of smoke (far above the front funnel). A second explosion must have followed that of the torpedo (boiler or coal or powder?). . . . The ship stopped immediately and quickly listed sharply to starboard, sinking deeper by the head at the same time.”

Aboard the Lusitania, Fisher and his companions went up to the deck and found a chaotic scene. With the ship listing, passengers rushed to lifeboats. “An effort was being made to lower the boat swinging just opposite the grand entrance. Women, children and men made a mad scramble about this boat which was smashed against the side throwing the occupants into the sea.”[3]

In the midst of the chaos, an officer told those still on deck, “Don’t worry; the ship will right itself.”[3] But that turned out to be wishful thinking. “He had hardly moved on before the ship turned sideways and then seemed to plunge headforemost into the sea.”[3]

Less than 20 minutes after it was hit, the Lusitania went under. Only six of the 48 lifeboats had launched successfully. The water bobbed with wreckage and dead bodies. Survivors grabbed on to whatever floating debris they could and prayed for a rescue.

Back in Washington, details coming by cable were sketchy and the extent of the tragedy was not fully realized immediately. Just past 6pm the Evening Star published an Extra! proclaiming “None Perish on Lusitania When Ship is Torpedoed,” a “fact” which the paper credited to the quick response of ships rushing to the scene after the attack.

The next day’s edition offered a very different – and sobering – headline: “51 Americans Reported Saved of 188 Aboard Lusitania: Indicated by Latest Estimates That 1,216 Persons Perished When the Big Liner Went Down.” It was a tragedy of epic proportion.

Dr. Fisher and Dorothy Conner were two of the lucky ones. When the ship was going down, they jumped into the water. As Dr. Fisher told reporters the next day, “I came up after what seemed to be an interminable time under water and found myself surrounded by swimmers, dead bodies and wreckage. I got on an upturned yawl, where I found 30 other people.”[3]

Eventually, Fisher was picked up by a tramp streamer, which had disguised itself as a Greek vessel (Greece was a neutral nation in 1915) to discourage another U-boat attack. He was taken to Queenstown, where he reunited with Conner who had also been plucked out of the water. The Washington papers celebrated their survival and that of fellow Washingtonian Frederick J. Gauntlett who had also been on board.

The sinking of the Lusitania caused outrage in Britain and the United States, which lambasted the incident as a brazen violation of international law prohibiting attacks on passenger ships. The German government countered that the liner was carrying war supplies for the British military and, thus, was a viable military target. While the American and British governments sternly denied these charges they were, in fact, true. In 2008, divers exploring the Lusitania shipwreck confirmed that it went down with over 4 million rounds of ammunition in its hull.

It seems Fisher may have sensed there was more to the story than what Washington and Whitehall were letting on. Despite his near death experience, he told the New York Times that he was not in favor of retaliation for the sinking of the Lusitania, “We were warned by the German Government. I, for one, do not want any official action by my country.”[4]

He was not so forgiving of the company that operated the Lusitania or the British admiralty: “I do not see how either the Cunard company or the admiralty can hold themselves free from blame for this tragedy. The authorities allowed a great ship loaded with valuable cargo to proceed through dangerous waters without a single torpedo boat as a convoy.”[3]

There is some evidence that these oversights were intentional on the part of the British, who hoped to draw the U.S. into the war against Germany sooner rather than later.

Of course, the United States would eventually go to war, but not until 1917. In the meantime, Fisher and Conner went on to France to assist with the creation of the Reckitt-Johnston Hospital.

Footnotes

- ^ “GERMANY WARNS PASSENGERS: Travel on British Ships at Their Own Risk, Says Embassy,” The Washington Post (1877-1922); May 1, 1915; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post; pg. 3

- ^ “Dr. Howard Lowrie Fisher,” The Lusitania Resource website. Accessed 4 May 2015.http://www.rmslusitania.info/people/saloon/howard-fisher/

- a, b, c, d, e “PUTS BLAME ON LINE: Precautions and Discipline Not Sufficient, Says Dr. Fisher,” The Washington Post (1877-1922); May 10, 1915; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post; pg. 3

- ^ “SHIP'S DISCIPLINE SHARPLY ATTACKED: Dr. Fisher of New York Blames Cunard Line and the Admiralty,” New York Times (1857-1922); May 10, 1915; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times with Index; pg. 2

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)