Remembering the Summer of 1960 at Glen Echo

You might not immediately associate roller coasters with racial equality, but more than three years before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March on Washington, Maryland’s Glen Echo Park was a focal point of the Civil Rights Movement. It made sense: since its opening in 1899, Glen Echo had been the premier amusement park for white Washingtonians. The park featured a number of modern roller coasters, a miniature railway, a Ferris wheel, an amphitheater, a pool: everything and more that other parks provided.[1]

But for all these years that the park enjoyed immense success, black children rode streetcars past the flashy rides and were denied access. Since 1940, the only amusement park that catered to African Americans in the area, Suburban Gardens, had been closed.[2] For the next 20 years, there existed no real leisure activities for blacks that were comparable with Glen Echo.

So in the summer of 1960, fresh off their successful effort to integrate Arlington’s lunch counters, Howard University student protesters and a biracial contingent from the community set their sights on desegregating the park. Joan Mulholland, a white activist who played a role in the protest and in later Civil Rights demonstrations, recognized the importance of integrating Glen Echo. “Going [there] was sort of a summer ritual,” she said in an interview with Maryland’s Gazette. “But of course it was all whites. So it was a pretty big symbol.”[3]

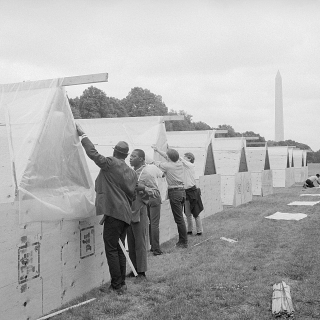

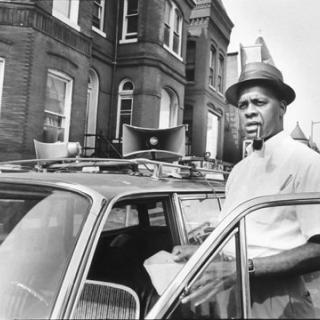

The picketing began the evening of June 30th. The Howard students, mostly members of the Nonviolent Action Group (N.A.G.), were led by Laurence Henry, a 26-year-old divinity student. Many of them, including Henry, had been involved in organizing and participating in previous local protests. Inspired by the Greensboro sit-ins of February 1960, they strove to achieve change without the use of violence. At 6 p.m., they gathered at the entrance of Glen Echo with placards that read “Glen Echo Should Echo Democracy,” “End Jim Crow at Glen Echo” and “Bigotry is No Fun.”[4]

Right off the bat, the protest differed from prior demonstrations. The 28 Howard students found considerable support in the white residents of nearby Bannockburn, and together they formed a diverse crowd of more than 60.[5] With the help of these community members, such as Mulholland, students left their placards at the gate and gained access to the park for the first time that same night. They headed toward the lunch counter, but it immediately closed when those working saw the racial makeup of the crowd. They then went to the ice cream machine, but management locked it down for the same reasons. 13 students finally headed to the famous Dentzel Carousel and boarded the painted animals.

While on the merry-go-round, state-deputized security guard Frank Collins approached Henry. In a conversation captured by reporter Sam Smith, Collins asked Henry his race and demanded he leave the park. Henry’s response perfectly encapsulates the ideals of the Civil Rights Movement: “I would like to know why I cannot come into your park… My race? I belong to the human race.”[6]

Unfortunately this answer didn’t win over Collins. While Henry was not immediately arrested, five students were. William L. Griffin, Cecil T. Washington, Jr., Marvous Saunders, Michael A. Proctor, and future Maryland State Senator Gwendolyn Greene (Britt) were detained for trespassing, and the rest were asked to leave the park.[4] But the next day, they were back in full force at the front gate.

The picketing continued throughout the summer and stayed relatively peaceful, despite counter-protesting from George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party. Henry and Paul D. Dietrich, a white George Washington University student, were arrested for a brief spat with Rockwell on July 3, but little came out of the dust up.[7] In general, the desegregationists far outnumbered the counter-protesters and found considerable support from the Glen Echo community. Things looked good. On July 5th Henry told the Washington Post: “The victory belongs to us… That park shall be opened by our effort. From this point it is just a matter of time.”[8]

The optimism was a bit premature. Protesters soon became frustrated that local authorities were taking little to no action in the desegregation of the park. In early July, they pressured the Montgomery County Council to pass legislation banning segregation in privately owned facilities that served the public, such as Glen Echo. Councilman Joe M. Kyle expressed his sympathy for the protesters, and stated, “they ought to be permitted to go where they want to go, but I’m not disposed to tell the management to run its business.”[4] Based on Maryland state law, the council did not have the authority to overrule the practices of a private company.

Determined to overcome this roadblock, the students decided to take their case to the next level. On July 8th, they filed a suit in the Federal District Court of Baltimore that sought “an injunction against the use of state police authority in enforcing the discriminatory policies of private concerns.”[9] In other words, they used what was held against them in the Montgomery County Council to their benefit: since Glen Echo Park was privately owned, the students argued that it had no authority to use public police forces for arrests. This legal counter-offensive was “expected to set an important precedent in civil rights.”[9]

By the end of the summer, it seemed some progress was finally being made. On September 13th, the Human Relations Committee of the Montgomery County Council, created to discuss the issues at Glen Echo, unanimously ruled that it would stop its bus service that transported white children to the park’s Crystal Pool until the pool was desegregated.[10] At the same time, those arrested for trespassing and disorderly conduct at the park earlier in the summer were found innocent, and the judge chided police for the unfounded charges.[7]

But when the park closed for the summer, its owners had still refused to desegregate. While the students were making important legal progress, they found their final goal stunted by those who held the reigns at the privately owned park. As they left their placards that fall, they vowed to return at the park’s opening in the spring. One local protester said he was ready to “walk with the signs for another eight months if necessary.”[11]

That winter, Bannockburn resident Hyman Bookbinder, newly appointed assistant to Secretary of Commerce Luther Hodges, had a better idea. A small part of the park’s property was leased from the Federal Government. Using his governmental connection, Bookbinder appealed to U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and asked if the park’s lease could be revoked if they continued their policy of segregation.[11] It worked.

With Kennedy knocking at their door, Glen Echo Park owners Abraham and Sam Baker gave in to desegregation on March 14th, 1961. As of the park’s opening on March 31st, Glen Echo would be open to all races for the first time in its 52-year history.[12] And victory didn’t stop there. The case filed in the Federal Court of Baltimore made its way up to the Supreme Court. Almost four years after the protests began, Chief Justice Earl Warren overturned the trespass convictions on June 23rd, 1964. Attorney Joseph L. Rauh, Jr. argued that since the park police were agents of the state, “the state was involved in enforcing discrimination.”[13]

The events at Glen Echo Park the summer of 1960 and the ensuing achievements proved to be monumental for the Civil Rights Movement. Not only did the picketers make groundbreaking legal precedents and succeed in the integration of the park, many were inspired to participate in additional large-scale protests. One Howard University student and N.A.G. member, Dion Diamond, was an integral part of the Southern freedom rides and was arrested more than 30 times between 1961 and 1963.[14] And he, along with many others, can always point to Glen Echo as a starting place.

Footnotes

- ^ Cook, Richard A. “A General History of Glen Echo Park,” Cabin John, accessed 16 June 2015, glenecho-cabinjohn.com/GE-40.html

- ^ Kelly, John, “Remembering Suburban Gardens: DC’s Only Amusement Park,” The Washington Post, 26 October 2013.

- ^ Calamaio, Cody, “Glen Echo Park celebrates 50 years of integration,” Gazette, accessed 10 June 2015,www.gazette.net/stories/06232010/bethnew223927_32548.php

- a, b, c McBee, Susanna and John Anderson, “5 Arrested in Glen Echo Sitdown: Negroes Protest Segregation at Amusement Park,” The Washington Post, 1 July 1960.

- ^ Lawson, John, “Glen Echo Arrests 5 Negroes in Sit-In,” The Washington Evening Star, 1 July 1960.

- ^ “A Summer of Change: The Civil Rights Story of Glen Echo Park,” NPS, accessed 9 June 2015, www.nps.gov/glec/learn/historyculture/summer-of-change.htm

- a, b “3 Convicted, 3 Acquitted in Bias Picketing Cases,” The Washington Post, 15 September 1960.

- ^ Anderson, John and Kenneth Weiss, “Glen Echo Pickets Win Support: NAACP Officials Request Negroes to Back Action,” The Washington Post, 5 July 1960.

- a, b “Wilkins and Randolph join pickets at Glen Echo Park,” The Afro-American, 20 August 1960.

- ^ “Montgomery Ends Children’s Outings To Glen Echo Park,” The Washington Post, 14 September 1960.

- a, b Feeley, Constance, “Glen Echo Park Opens Its Doors to Negroes After Year of Protest,”The Washington Post, 15 March 1961.

- ^ “Integration Set at Glen Echo,” The Washington Evening Star, 14 March 1961.

- ^ “Enforcing Discrimination With Agent Of State Is Key to Glen Echo Decision,” The Washington Post, 24 June 1964.

- ^ “Crazy Dion Diamond: A 1960s Rights Warrior in the Suburbs,” Washington Area Spark, accessed 12 June 2015, washingtonspark.wordpress.com/2013/01/20/crazy-dion-diamond-a-1960s-rights-warrior-in-the-suburbs

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)