How the Kennedy Center was Created

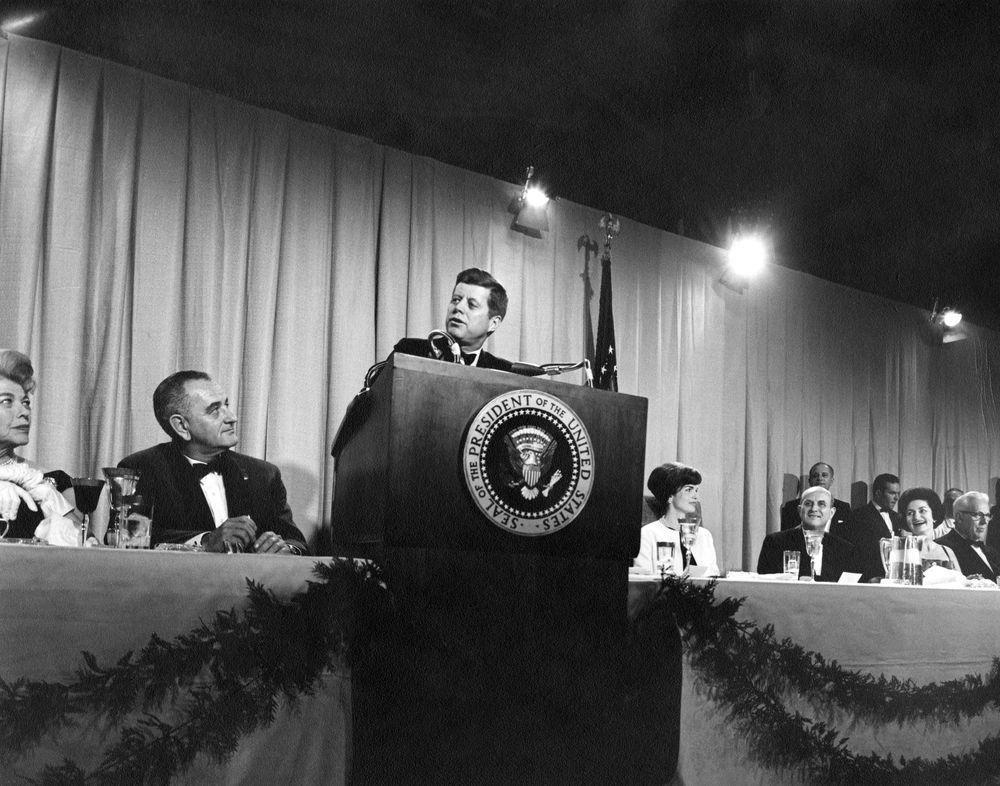

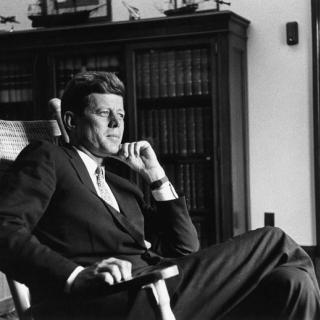

“In a democratic society, we have a special responsibility to the arts, for art is the great Democrat, calling forth creative genius from every sector of society, disregarding race, or religion, or wealth, or color. The mere accumulation of wealth and power is available to the dictator and the democrat alike. What freedom alone can bring is the liberation of the human mind and spirit, which finds its greatest flowering in the free society. Thus in our fulfillment of these responsibilities towards the arts, lie our unique achievement as a free society.”

– President John F. Kennedy speaking at An American Pageant of the Arts on November 29, 1962 [1]

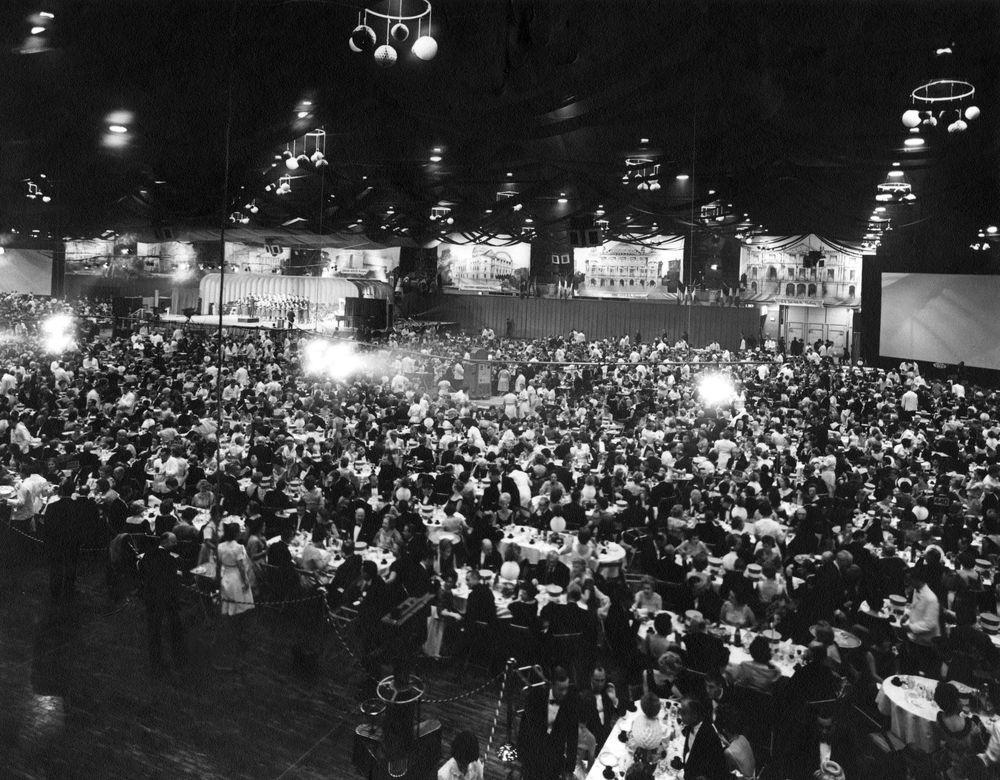

At 7 p.m. on November 29, 1962, 5,000 Washingtonians dressed in black ties and furs arrived at the D.C. National Guard Armory for a $100-a-plate dinner, and fundraising show titled An American Pageant of the Arts. At 9:30 p.m., “with the blare of herald trumpets from the United States Navy Band, the President and Mrs. Kennedy walked into the glare of spotlights in the darkened Armory and up to their places at the head table.”[2] President and Mrs. Kennedy started the event by addressing the crowd about the importance of the arts in fostering American culture and a healthy democracy. Afterward, the master of ceremonies for the evening, Leonard Bernstein, took over and the 2 hour and 43-minute show, featuring some of the greatest performers in music, literature, and comedy, began.

The show kicked off a $30 million fundraising initiative to raise money for the construction of a National Cultural Center on the bank of the Potomac.[3] Efforts to construct the Center began in 1958, when President Dwight Eisenhower signed bipartisan legislation authorizing its creation. Despite the approval of this important legislation, fundraising efforts didn’t really take shape until John F. Kennedy became President.

The Kennedys took Washington by storm when they arrived in 1961. JFK and Jackie embodied qualities of class and culture, and promoted them extensively throughout their time in the White House. One of the cultural initiatives that they took hold of was carrying out the completion of the new cultural center, for which progress had remained stagnant since the Eisenhower Administration. In an attempt to boost fundraising money to construct architect Edward Durell Stone’s building, Kennedy came up with the idea to hold a variety show that would feature artists of different genres coming together to support the arts, and a national home for them in Washington.

On the evening of the show, hoards packed the Armory, and thousands more watched a closed-circuit telecast at the Capitol, the Indian Spring Country Club, and six area university campuses. As The Washington Post dubbed it, the show was “a city-wide sellout.”[4] In addition to the 20,000 people watching in the District, sixty other cities across the country offered the closed-circuit telecast to viewers both in their homes, and at other small benefit dinners that would split their proceeds 50-50 with the National Cultural Center.[5]

The show did not go off, however, without a slew of technical problems. Despite efforts to improve the acoustics in the hall, many guests in the “barn-like Armory,” couldn’t hear the show and ended up leaving early. The President and those at the head table, however, were able to hear, and they enjoyed the performances immensely.[6]

On the broadcast side, viewers had to endure the occasional black screen, slanted picture, and oil bubbles spotting the lens. On top of all of this, the program went 45 minutes over schedule. Interestingly, despite all of these issues, the show got great reviews. The Washington Post remarked that most viewers “were there, they said, to benefit the Cultural Center, not particularly to see the show. Most said they frankly didn’t expect the show to be anything and that they were pleasantly surprised.”[7]

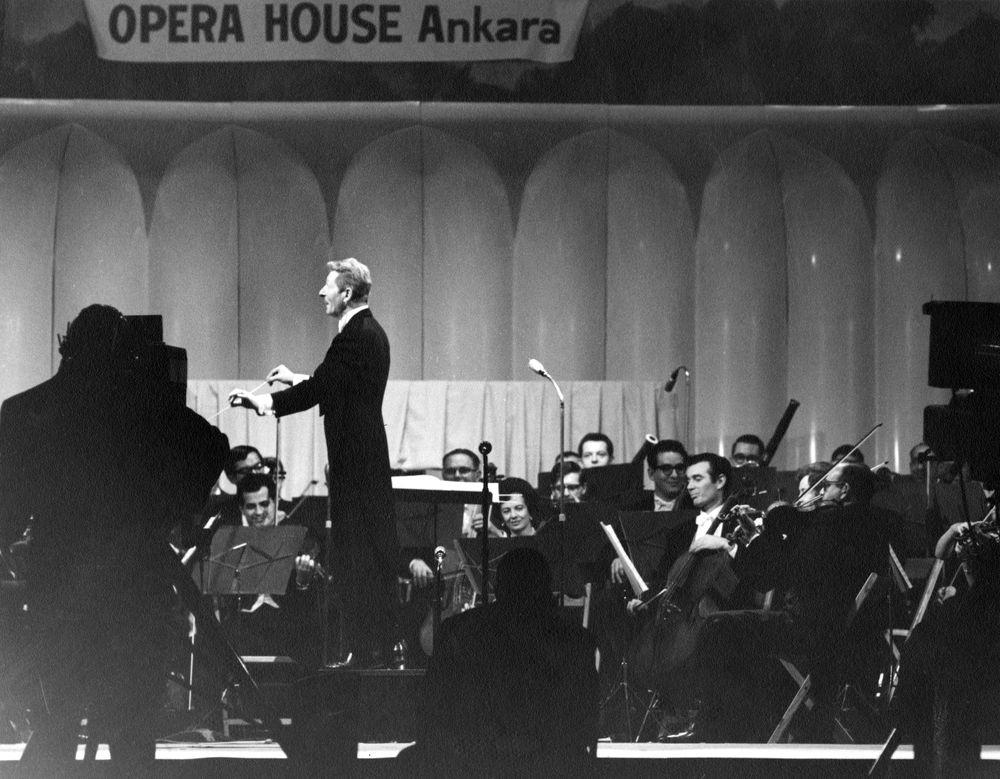

And “pleasantly surprised” seems like an understatement to explain the top-notch performances that took place that night. After words from the President, actor Danny Kaye took to the podium and led the National Symphony Orchestra in an act that has been described as a satire of great conductors.

After the rousing bit, Leonard Bernstein took over as emcee and introduced the rest of the show, which also included “Van Cliburn playing Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 in C-Sharp Minor on a piano that he had moved from New York to Chicago for the show,” great cellist Pablo Casals in a prerecorded performance, and everything from “Bach to jazz” and “ballet to tomfoolery” by Marian Anderson, Henry Belafonte, Robert Frost, Bob Newhart, Frederic March, Richard Tucker, and the United States Navy Band.[8]

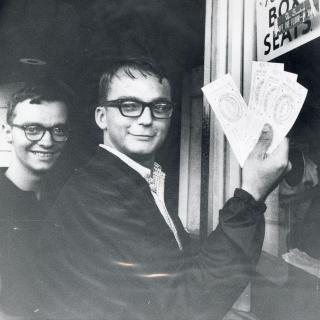

Perhaps the most memorable performance from the pageant, however, was the debut of a 7-year-old cello prodigy playing Breval’s Concertino No. 3 in A Major while accompanied by his 11-year-old sister on the piano.[9] Leonard Bernstein introduced this young musician:

“An aspect of that double stream of art I mentioned earlier flowing into and out of America, has long been the attraction of our country to foreign artists, and scientists and thinkers, who have come not only to visit us, but often to join us as Americans, to become citizens of what to some has historically been the land of opportunity and to others the land of freedom. And in this great tradition, there has come to us, this year, a young man aged 7, bearing the name Yo-Yo Ma. Now Yo-Yo came to our attention through the great master Pablo Casals who had recently heard the boy play the cello. Yo-Yo is, as you may have guessed, Chinese, and has lived up to now in France—a highly international type. But he and his family are now here. His father is teaching school in New York, and his 11-year-old sister, Yeou-Cheng Ma, is pursuing her musical studies, and they are all hoping to become American citizens. We shall now have the pleasure of hearing Yo-Yo Ma, accompanied by his sister Yeou-Cheng Ma, play the first movement of the Concertino No. 3 in A Major, by Jean-Baptiste Breval, who played, taught, and composed for the cello 150 years ago in France. Now, here’s a cultural image for you to ponder as you listen. A 7-year-old Chinese cellist, playing old French music, for his new American compatriots. Welcome Yo-Yo Ma and Yeou-Cheng Ma.” [10]

A young Yo-Yo Ma, who was “bashful” about having lost a tooth a few days earlier, impressed the audience immensely, and high praise in the newspapers the next day inspired him to “work even harder to master his instrument,” which slowly rocketed him into stardom as a world-renowned and highly celebrated cellist today.[11]

At the end of the show, President Eisenhower offered closing words via large screen telecast from Augusta, Georgia—with President Kennedy opening the pageant, it was only appropriate for the president who started the cultural center initiative to close the event. Eisenhower’s presence helped keep the focus of the Cultural Center initiative bipartisan. Potential donors could see that the Kennedys and the Eisenhowers were united in the indispensable goal of acquiring “a center of the performing arts that befits a world capital,” because “the cause is one that transcends party and state lines, and the campaign was begun in a thoroughly American way.”[12]

The pageant was highly successful and wildly popular with everyone who had the opportunity to attend in person, or watch the telecast. It was not, however, able to generate enough money on its own to support the groundbreaking for the Center, and unfortunately, JFK was also not able to complete that mission in his lifetime.

It wasn’t until after Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, that thousands of dollars in donations made in the late President’s honor flowed in to support the construction of this building. It was also at this time that Congress decided to designate the future National Cultural Center as a “living memorial to Kennedy,” and allocated $23 million to finally construct what would become the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[13] President Lyndon B. Johnson broke ground for the Kennedy Center on December 2, 1964, and it officially opened on September 8, 1971.

Kennedy’s fundraising efforts made during The American Pageant for the Performing Arts set the example for the importance of the arts in Washington, and the Nation for many years to come.

“Our culture and art do not speak to America alone. To the extent that artists struggle to express beauty in form, and color, and sound. To the extent that they write about man’s struggle with nature, or society, or himself. To that extent they strike a responsive chord in all humanity.”

–JFK, November 29, 1962

Footnotes

- ^ HelmerReenberg. n.d. November 29, 1962 - President John F. Kennedy Speaking at American Pageant of the Arts Dinner. Accessed November 14, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40HP3NuTMf8&t=177s.

- ^ The Evening Star. 1962. “Throngs Join Kennedy In Culture Fund Drive,” November 30, 1926.

- ^ Reporter, Jean M. White Staff. 1962. “Cultural Show Seen By 400,000: 20,000 Attend Benefits Here For New Center.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., November 30, 1962. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/141667639/abstrac….

- ^ Reporter, Jean M. White Staff. 1962. “Kennedy, Eisenhower, Top Talent Spark Art Pageant.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., November 29, 1962, sec. City Life. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/141638888/abstrac….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Evening Star. 1962. “Throngs Join Kennedy In Culture Fund Drive,” November 30, 1926.

- ^ The Evening Star. 1962. “Pageant Viewers’ Comfort Varies,” November 30, 1926.

- ^ GOLD, BILL. 1962. “THE DISTRICT LINE: $100 Pageant Adds Yo-Yo’s Strings.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., November 26, 1962, sec. Comics. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/141659441/citatio…; Reporter, Jean M. White Staff. 1962. “Cultural Show Seen By 400,000: 20,000 Attend Benefits Here For New Center.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., November 30, 1962. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/141667639/abstrac….

- ^ The Evening Star. 1962. “Throngs Join Kennedy In Culture Fund Drive,” November 30, 1926.

- ^ The Kennedy Center. November 29, 1962. Leonard Bernstein Introduces 7-Year-Old Yo-Yo Ma at the American Pageant for the Arts. Accessed November 14, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7G2QKzp78Zs.

- ^ Weatherly, Myra. 2007. Yo-Yo Ma: Internationally Acclaimed Cellist. Capstone. pp 9-14.

- ^ The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. 1962. “Kulturkampf,” December 2, 1962, sec. Outlook; The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. 1962. “Kulturkampf,” December 2, 1962, sec. Outlook. https://search.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/141584595/abstrac….

- ^ “Kennedy Center: History of the Living Memorial.” n.d. Accessed November 16, 2017. http://www.kennedy-center.org/pages/about/history.

![Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington D.C. (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635609/. (Accessed November 21, 2017.) Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington D.C. (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635609/. (Accessed November 21, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_full_width/public/17415v.jpg?itok=BPrkj80u)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)